Alberta has among the continent’s most permissive policies on cleaning up inactive oil and gas wells, and that could saddle taxpayers with more than $30 billion worth of liabilities, according to a new report.

While most North American jurisdictions require companies to clean up and restore non-producing oil and gas wells in a timely fashion, Alberta doesn’t, says the report by University of Alberta economist Lucija Muehlenbachs, also a visiting fellow at the U.S. think tank Resources for the Future.

Most jurisdictions require companies to shut down and clean up wells that have been inactive for specified periods. Alberta allows companies to say wells are “suspended” indefinitely.

“Alberta is one of the more lenient jurisdictions as it has no limit set on the length of time a well can remain suspended,” explains Muehlenbachs in a briefing paper released last week for the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary.

North Dakota, which has no backlog of inactive wells, requires that wells that been inactive for 12 months be properly plugged and decommissioned immediately or within a two-year time period.

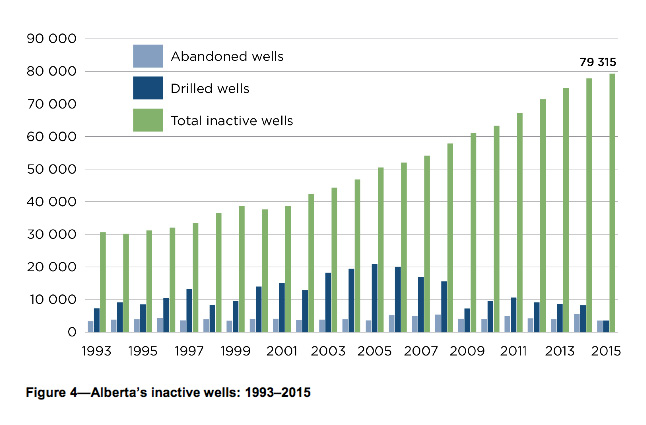

But Alberta’s lax policies have helped the number of inactive wells triple in the last 20 years from 25,000 in 1989 to 81,602 inactive wells as of Nov. 26, 2016.

That means that one-third of the 255,000 oil and gas wells in Alberta are inactive. More than 10,000 of the inactive wells have been sitting idle for decades.

Inactive wells pose a variety of environmental and financial risks to the public. Most inactive well sites leak methane and can contaminate soil and groundwater and support invasive weed growth. They also fragment ecosystems, devalue property and prevent farmers making full use of their land.

The Alberta Property Rights Advocate Office warned in its annual report last year that conflicts between landowners and oil and gas companies were escalating as companies, struggling with low oil prices, walked away from lease agreements and reclamation responsibilities.

“If a bankrupt company abandons a well site, the landowner may find themselves continuing to ‘host’ that well site, along with any environmental problems, for years, possibly even decades before it is reclaimed,” explained the report. “Sites requiring reclamation can suffer impacts to market value or landowner’s ability to sell the property for the duration of time it takes for that site to be reclaimed.”

Inactive wells also represent a staggering potential liability for taxpayers: they can cost anywhere from $50,000 to millions of dollars to plug, abandon and reclaim.

The longer these wells remain inactive, the more likely they will become “orphans” as their owners go bankrupt due to volatile oil markets.

Orphaned wells tend to cost more to reclaim because they have fallen into a state of disrepair and have caused greater environmental contamination.

With low oil prices, the number of bankrupt operators and orphan wells has grown rapidly in Alberta, Saskatchewan and B.C. In the last 24 months, the number of orphan wells awaiting cleanup has increased from 162 to 768 in Alberta.

In Alberta, the industry-funded Orphan Well Association, which now spends $30 million a year on cleaning up abandoned wells, can’t handle the workload.

By one estimate, it would take the agency, at current funding levels, 177 years to pay for more than $30 billion in oil patch liabilities for inactive wells and other abandoned facilities.

By having the option to suspend a well instead of cleaning it up, “companies do not have strong incentives to internalize either the environmental risks or future potential liabilities they impose on industry should they go bankrupt,” concludes Muehlenbachs in her report.

Result of permissive policies

For nearly two decades, Alberta’s permissive policies have allowed companies to avoid costly environmental cleanups by “suspending” production and sitting on inactive wells indefinitely.

“The only way to prevent the province’s growing number of inactive wells from remaining an ongoing risk to the public is by limiting the ability of owners to keep wells inactive as long as they like,” recommends the paper. “Policies should recognize that most inactive wells will likely never produce oil or gas again.”

Critics of Alberta’s lax policies say change is long overdue, but neither the Tories nor the New Democrats have tackled the issue.

“Alberta has to enforce serious time limits and behave like other jurisdictions in the world,” Brent O’Neil, an oil patch driller told The Tyee. He recently proposed a radical program to put oil patch workers back to work by focusing on cleanup and well decommissioning in the province.

“We have to get the oil companies to clean up their mess and we need to be proactive now. We have been reactive for 30 years,” added O’Neil.

He characterized the Alberta Energy Regulator’s current approach to the problem, the Inactive Well Compliance Program, as covering-up the real breadth of the issue.

It gradually encourages the industry to turn inactive wells into suspended ones, which means they require more monitoring. But the name change does nothing to address the growth of unfunded reclamation liabilities in a province unprepared for low oil prices, adds O’Neil.

The regulator says “suspended wells” pose minimal risk to the public, but admits “the cumulative number of wells is a concern.”

In 1997, Alberta’s oil patch regulator briefly introduced a Long Term Inactive Well program to address inactive wells. But it didn’t last long.

The policy forced industry to clean up over a five-year period. Industry opposition led them to shut down the program.

The replacement Liability Management Rating reports growing liabilities on a monthly basis and collects small security deposits from companies when their liabilities exceed their asset values.

According to reports from that program, almost 45 per cent of the province’s oil companies no longer have enough producing wells to pay for the proper cleanup of their inactive ones. As of January 2017, 353 companies with more than 13,000 wells fell below the threshold at which they could pay for their cleanup costs.

To date the LMR program has $200 million worth of security deposits to cover liabilities of more than $30 billion.

Critics such as O’Neil say the LMR program overestimates asset values for an aging industry and grossly underestimates the scale of rising liabilities.

By suspending inactive wells indefinitely, companies can hide their liabilities from bankers and not have their loans called, explained O’Neil. “The program benefits producers at the expense of the public.”

But industry has long argued that inactive wells aren’t really liabilities because higher oil prices and better technologies might lead to their reactivation in the future and thereby make them productive assets again.

Muehlenbachs, however, looked at historical decision-making in the oil patch and discovered that wasn’t the case.

“Even with high price increases, the number of wells that are reactivated are really few, and they don’t produce much oil and gas either,” said Muehlenbachs in an interview.

Big Oil asks for cleanup subsidies

As conventional oil production declines across Western Canada, the problem of inactive wells has grown exponentially. There are 20,000 non-producing wells in Saskatchewan and 10,000 abandoned or suspended wells in British Columbia.

In 2012 Saskatchewan’s auditor general warned taxpayers that government legislation “does not address the timely cleanup of inactive wells and facilities,” and that “there is a future risk that a portion of the $3.6 billion” cleanup bill “may be borne by the ministry and hence Saskatchewan residents.”

Many companies won’t have “sufficient financial means to clean up their wells and facilities or they may not be identifiable or locatable when cleanup is needed,” added the report.

Since then the problem has worsened. Saskatchewan’s latest orphan wells annual report found that “total industry liability is increasing more rapidly than total industry asset value. While industry activity is increasing, so is the number of mature wells reaching the end of their economic life, adding additional liability to the system over time.”

Similar problems are being encountered with B.C.’s liability management program as “the number of at-risk producers and unsecured liability” increases.

As a consequence of Saskatchewan’s lax policies, Premier Brad Wall asked the federal government in 2016 for $156 million to clean up a fraction of the problem: 1,000 of some 20,000 non-producing wells in his province.

But critics said that request violated the principle that polluters should pay for their cleanup costs.

The “polluter pays” principle requires that the oil industry be the key entity paying for work to carry out such cleanup work, argued Darryl McMahon, the principal director of RestCo, a firm concerned about energy sustainability and resilience, in a letter to the federal government.

“Unfortunately, the oil industry have not developed effective, affordable approaches for doing so, or this issue would have been resolved in the past.”

The Petroleum Services Association of Canada has also asked federal taxpayers for a $500-million handout in order to clean up “more than 75,000 inactive wells requiring downhole wellbore abandonment and surface reclamation.”

A failed policy

Muehlenbach’s study is not the first to draw attention to Alberta’s failed policy.

One recent research paper concluded that the province must not only introduce timelines for abandonment and reclamation, but also collect upfront security bonds from industry as well as create a legacy fund, jointly funded by industry and government.

Reports from Ecojustice have also documented the problem.

“In the absence of such regulated timelines, Albertans may be left to grapple with an ever-increasing number of inactive wells and the environmental and safety risks associated with them for another 25 years — to say nothing of eroded trust in the [regulator] or future regulatory bodies,” concluded Barry Robinson, a lawyer with Ecojustice.

The state of Colorado has set regulated timelines for well abandonment and reclamation and, as a result has one inactive well for every 18 active wells (2,947 inactive wells; 49,732 active wells) as of 2014, Robinson noted. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: