An international body released a report Monday accusing Canadian law enforcement of failing to protect aboriginal women from violence, disappearances and murder, while calling for an inquiry into the matter.

The report was issued by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which works within the Organization of American States, comprised of countries throughout the America and founded in 1948 to promote solidarity among North and South American nations.

The report found that aboriginal women in Canada go missing four times more than non-aboriginal women.

"In cases where charges have been laid, 49 per cent of the women were killed by strangers or by acquaintances, as opposed to family members, a significantly higher rate than the rest of the population," read the report. "This indicates that indigenous women and girls may be at greater risk for victimization by sexual predators, serial killers, and other criminals."

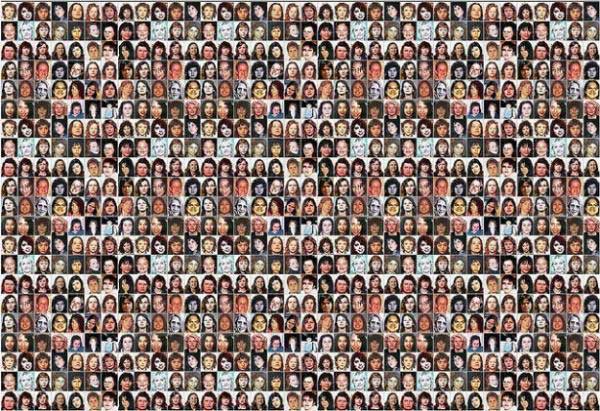

The report chiefly addressed missing women in British Columbia, which it said accounted for 160 of the 582 in the database of the Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC), though the number of missing women is generally said to be 1,000 across Canada.

The case of Canada's missing indigenous women has made headlines for some time, and Prime Minister Stephen Harper recently sparked fresh outrage in a year-end interview with the CBC when he said a national inquiry into the disappearances is not high on the government's radar.

In light of the new report, The Tyee sought insight from two experts on solutions that could help better protect indigenous women.

Dawn Harvard, first vice-president of NWAC and Leilani Farha, executive director of Canada Without Poverty and United Nations special rapporteur on adequate housing, whose organizations provided data to support the report, pitched four ideas.

Improve emergency response times:

The report found that aboriginal women in Canada more frequently suffer "more severe" forms of domestic violence than non-aboriginal women in Canada. Aboriginal women were also more likely to fear for their lives as a result of abusive partners.

When a situation at home is heating up, law enforcement presence is obviously crucial, Harvard said. But emergency workers, such as police, can become desensitized to repeated domestic violence at a particular home and not respond as quickly as they could when a call comes in at that address.

"We know these things escalate," Harvard said, with assaults tending to become more violent with subsequent calls.

The same kind of desensitization happens with family and friends if they repeatedly help a woman move out of a bad domestic situation that she later returns to, Harvard said.

"That's when things get much worse for the woman in that situation, because slowly her supports dwindle away," Harvard said.

Harvard said responders should be specifically trained to support aboriginal women on the front lines.

Improve housing for aboriginal women:

The UN special rapporteur on adequate housing noted in a 2009 report that aboriginal women face the most severe housing problems in Canada, both in urban and rural areas.

A lack of safe, affordable housing can keep women in unsafe situations, or see them leave town through unsafe means, such as hitchhiking, where they become vulnerable to predators, said Farha.

"It's not uncommon, especially because of discrimination against indigenous women and perceptions about indigenous women," she said. "Perceptions that they will have a sexual relationship just like that."

If they do manage to make it to another city, with no money or support network, prostitution can become a way to survive, Farha said, leaving them vulnerable to more violence.

Provide better support for education:

A good education can mean a good job, and that can mean a more stable, safe living situation, making education a key component of any serious plan to prevent violence against aboriginal women.

"It is one of the most important places where small financial investments and support can yield the largest impact in terms of improving lives and conditions," Harvard said.

"There's also a trickle down effect, not only for the specific woman who would be getting the increased education, but for her family... the education rate of the mother trickles down to improve the education rate of the children."

In addition, a turbulent home life, where parents are unable to keep enough food on the table, can be seen as an issue of neglect rather than poverty. That can lead to children being seized by authorities, Harvard said, making it harder for the child to pursue a strong education.

Treat the missing women issues as a human rights case:

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights report said it "strongly supports the creation of a national-level action plan or a nationwide inquiry into the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls."

Farha said groups like hers will continue to push for a full inquiry into the more than 1,000 missing aboriginal women in this country.

She said there are obligations by the Canadian government to treat this as a human rights issue. Canada often demands other nations live up to their human rights obligations, she said, but is ignoring its own problems.

"The human rights approach puts the people who are harmed at the centre, and the people who are harmed are saying 'We want an inquiry,'" she said. "That is a very, very important and good first step." ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics, Health, Indigenous, Housing, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: