It is not yet noon. A man sits at a table in a bar sipping clear liquid from a tumbler with ice and two wedges of lime. He wears slacks, a blazer, a red polo shirt with thin white horizontal stripes and sneakers. His thin hair is carefully brushed across the top, the way he has combed it for decades.

The bar buzzes with activity. The man sits alone, though most seats in the house have been turned to face in his direction. He is watched as he nurses a bottle of sparkling water, gazing off into the distance.

He looks like a retired assistant bank manager waiting for the rest of his foursome at the local golf club. In time, some others in the bar find the nerve to interrupt his revery. They all have a story. Where they were when Joe Carter hit his touch-'em-all homer. How they marveled at Ichiro's magic. What they thought when Fred McGriff was traded. He has heard all of this before, many times, yet listens patiently, adds anecdotes of his own, shakes hands, maintains eye contact, remembers names. You get a sense of the impression he must have made on the parents of a prospect.

This is Pat Gillick when Pat Gillick is not doing what Pat Gillick does best, which is building championship baseball teams. He was the architect of the Toronto Blue Jays powerhouse that won five division championships in nine seasons, a time in which he gained the nickname Stand Pat for his reluctance to make too many trades. After back-to-back World Series wins in 1992 and 1993, Gillick left for the West Coast, where he belied his nickname by trading the greatest player in Seattle Mariners history, Ken Griffey, Jr. The Mariners went on to win a record-tying 116 games in 2001.

If he earned his bachelor's degree with the Jays and his master's with the Mariners, Gillick completed his baseball doctorate with the Philadelphia Phillies. They won the World Series in 2008, the club's second championship in 125 years.

Such astute judgment in putting together teams has earned Gillick induction in the Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, N.Y.

Gillick's minor-league odyssey

Gillick, 75, now a special assistant to the Phillies, came to Victoria from his Seattle home recently to promote the all-star game of the West Coast League, an amateur summer circuit for collegiate players, most of them American.

He was at a downtown Victoria bar one morning to speak to fans and players. Four of the five Victoria HarbourCats named to the all-star team were in attendance. (Alex DeGoti, an infielder from Miami, is only 18 and so could not attend the event. Also worth mentioning: The Blue Jays have not won a World Series in his lifetime.) Gillick spoke to them, and when introduced to Austin Russell who is from Victoria, he said, "Keeping these guys out of trouble, I hope."

Gillick knows what kind of adventures ball players can get up to while on the road. For five seasons, he kicked around the minor leagues playing for such teams as the Stockton (California) Ports, the Little Rock (Arkansas) Travelers and the Fox Cities Foxes of Appleton, Wisconsin.

He never wore a major-league uniform. It was on the buses rolling through darkened countryside that Gillick fed his faultless memory, memorizing the Sporting News baseball newspaper as though he was a lawyer studying the criminal code.

The accomplishments of this front-office savant have overshadowed his own playing career, which is little regarded and often ignored. Though Gillick didn't make it to the parent Baltimore Orioles, he could see the difference between those who did (like Rochester Red Wings teammate Davey Johnson, who had a long playing career and is now manager of the Washington Nationals) and those who didn't, like him.

Gillick's minor-league odyssey also took him to Vancouver for part of the summer of 1960.

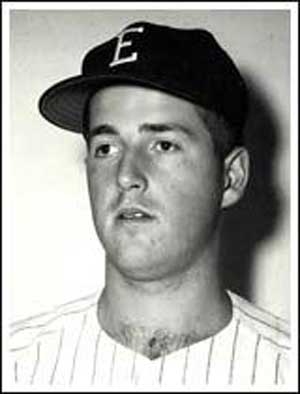

A left-handed pitcher out of Chico, California, where his father was county sheriff, Gillick went 11-2 with the Foxes, a class-B team, when he leapfrogged to triple-A baseball, just one level below the majors. He arrived on the Vancouver Mounties as a 22-year-old pitcher with nothing but bright prospects ahead.

His stay in Canada would be brief and not wholly positive. He managed a single victory against six losses. At the bar, he was asked if he remembered his only victory in Vancouver in a game played 53 years ago.

"Against Sacramento," he responded immediately.

A newspaper account said the young pitcher "showed the poise of a veteran" while "exhibiting a great talent for working his way out of trouble."

He picked off two base runners in a game played at Capilano (now Nat Bailey) Stadium, struck out five, and got out of a jam in the ninth to defeat the Solons 3-2 for the complete-game win. Gillick even remembered the pitcher he defeated, Claude Raymond, a 23 year-old nicknamed Frenchy from St-Jean, Quebec.

On reflection, the game before 3,072 fans on Aug. 9, 1960, was a highlight of his playing days.

Gillick was with the Mounties for only a few weeks. He roomed with Bo Belinsky, a fellow left-handed prospect whose wildness on the mound was matched by his wildness off it. Belinsky was a pool shark and a bon vivant who later in life squired Hollywood starlets such as Tina Louise, Ann-Margaret, and Mamie Van Doren; the latter to whom he proposed though never married.

How did the sheriff's son get along with the notorious wildman as a roommate?

"I didn't have him as a roommate," Gillick replied straight-faced. "I roomed with his suitcase." It's an old baseball line, but still funny.

George Bamberger, a wily veteran who was a playing coach at the time, provided Gillick insight on pitch selection. Like a matador preparing a bull for the coup de grace, Bamby, as he was known, was a master on setting up batters for a decisive pitch.

Gillick has fond memories of the Mounties, who were managed that year by George Stalling.

"We had Ray Barker, Jim Finigan, Jim Dyck, Charlie White, Howie Goss..." The names rattled off as though he was reading from an old scorecard. It was hard to believe he had played in only seven games for the Mounties.

The following season had him playing in Little Rock just four years after the Arkansas capital was embroiled in an ugly battle over desegregation of Central High. Travel in the Southern Association -- from Nashville to Chattanooga to Shreveport to Atlanta to Birmingham -- was an eye-opening introduction to Jim Crow for an athlete from California. "I was stunned," he said.

Gillick had earlier played baseball in Alberta as a college student looking for a few extra dollars in the summer. He hitchhiked north to pitch for the Vulcan Elks and the Granum White Sox.

Like father, like son

Gillick came to baseball through his father, a larger-than-life figure in Chico. Larry Gillick was born in 1909 in Amador County in California's Sierra Nevada range; gold-rush country in which gold is mined to this day. Larry was a right-handed pitcher who kicked around semi-professional baseball in his home state for several years before joining the class-D San Diego Aces in 1929. The hurler leaped up baseball's alphabet ladder with a promotion to the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League, in those days a double-A circuit.

The pitcher stood six-foot-two and weighed 205 pounds, a big man for his generation (and an inch taller and 20 pounds heavier than his son). In six seasons in the Coast league, he had a record of 35 wins and 39 losses. An injury shortened his playing career. A stint as a deputy in the Chico police department was interrupted by the attack on Pearl Harbor. Gillick served as a gunnery sergeant in the Marine Corps during the war. Soon after returning home, friends convinced him to run for sheriff. Though a self-described poor politician, the lawman won eight consecutive elections and held the post for 32 years.

On his retirement in 1982, he was described in a newspaper profile as the "rock-throwing sheriff" of Butte County, never once having fired his gun in three decades of keeping the peace. He once floored a suspect by hitting him in the back with a thrown stone. When asked why he never used his sidearm, the sheriff said, "I thought I might hurt someone."

Not that he was soft. In the 1960s, a madame from Wyoming showed up in the county to provide services for construction crews working on the Oroville Dam. "You put any whorehouses in Butte County," he told her, "you better put them on wheels because I'm going to be after you."

The sheriff wore a brown stetson and a thin black tie as part of his uniform. On weekends, he took a traveling pancake kitchen to fairs and county functions to raise money for the baseball and football teams he coached. He had a refrigerator, coffee machine and portable grill inside a 16-foot trailer. This was later replaced by a 40-foot trailer from which he sold pancakes, sausages, eggs, juice and coffee.

"He'd have these guys in jail for drunk driving, or not paying child support," Pat Gillick said. "He'd have them working on the Little League ball fields, trimming the grass and painting the stands. Others would grow vegetables on the prison's 40 acres. He'd tell them that if any ran away he'd put them in solitary."

A thinker

Gillick made his debut in Organized Baseball with Stockton in 1959. Unknown to him, his father watched from the stands. He had pitched on the same diamond a quarter-century earlier.

After five seasons in the minors, Pat decided to call an end to his pursuit of a playing career. A dazzling curve ball was not paired with a fastball of sufficient oomph, and lingering problems with control hampered his effectiveness. He felt he was a marginal player at best.

By then, Gillick already had a reputation as a thinker. (Kids with a college education were still a rarity on many baseball rosters.) "I don't think there is a line in the Sporting News he doesn't read and remember," manager Earl Weaver told the paper. "His memory is fantastic. I would have to say he knows more about ball players all over the country, from class-D to the majors, than anybody I have ever met." So prodigious was his memory for names, teammates called him Yellow Pages Gillick.

With a business degree on hand, he was working on completing a master's. Instead, he wound up taking a job with the expansion Houston Colt .45s (now the Astros). His big signing was an athlete from the Dominican Republic named César Cedeño. A local birddog named Epy Guerrero had made the negotiations go smoothly, so Gillick hired him as a scout. They would be the pair -- Guerrero emotional and mercurial, Gillick stoic and profound -- who would make the Blue Jays a powerhouse with the overlooked talent of a Caribbean island.

Gillick's plaque at the Hall of Fame hails him as a "brilliant talent evaluator" with a "remarkable memory and uncanny ability to shape rosters."

He is ruthless when circumstance demands it.

"You can't be fainthearted in this business," he told the crowd in Victoria.

In 1990, he made one of the most dramatic deals of his career, trading popular slugger Fred (Crime Dog) McGriff and shortstop Tony Fernandez from Toronto to the San Diego Padres. Roberto Alomar and Joe Carter would be keys to the Blues Jay winning those World Series, but that was still in the future.

After making the deal, Gillick prepared to return home to Toronto. He called his wife from the airport to let her know when to expect him. He also broke the news to her that he traded away McGriff, her favourite player.

"There was a long pause," Gillick recounted. "Then she said, 'Why don't you come home as fast as you can before you screw up the team anymore.'" ![]()

Read more: Travel

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: