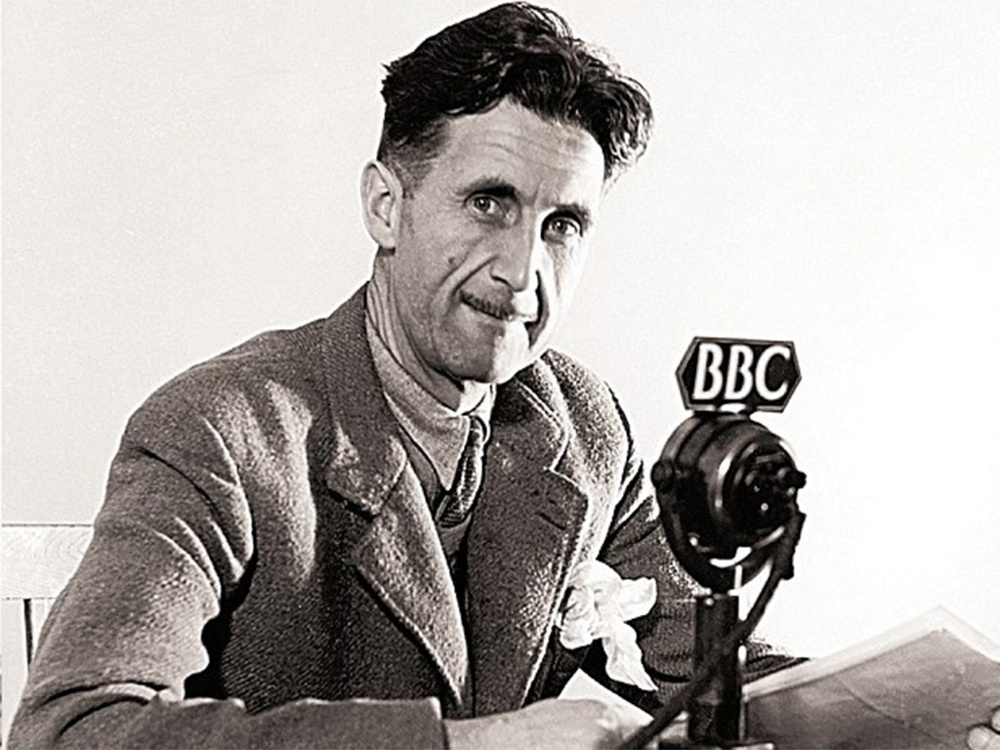

If you need some prickly bits of hope and thorny rationality in these times, George Orwell is your man. The English author of such seminal texts as 1984, Animal Farm and Homage to Catalonia is the subject of American writer Rebecca Solnit’s new book, Orwell’s Roses.

The essay collection, conjoined loosely by Orwell’s life and work, is delicate and perambulating, but also studded with bedrock ideas, emerging like boulders out of deep research and analysis. One moment you’re bobbing along with Solnit’s graceful prose; the next you run face first into a sentence so adamantine in its acuity, that it literally takes your breath away.

It’s a bit akin to getting hit in the head by a rock, but in a good way. You come away feeling stunned, but also profoundly impacted.

In essence, Solnit uses the figure of Orwell to draw correlatives between then and now, not only in realm of politics and culture, but in more deeply personal ways between herself and Orwell.

The same struggles that he endured, around money, health, relationships and writing, set against a backdrop of world-altering events like the Second World War, echo the current moment in time. As it was then, so it mostly is now, with writers and artists trying to make sense of things as they’re living through them.

In groping for some greater understanding of the state of the world, Orwell’s writing, as well as his dedication to the smaller pleasures of life — gardening and walking — offers a surprising amount of sturdy hope.

Orwell was an astute caller out of bullshit, which is also deeply helpful at the moment as there are mountains of it everywhere. In this aspect, Orwell’s Roses is a powerful reminder of the human propensity for denying reality.

As Solnit says, it’s easy to draw comparisons to the rise of fascism in Orwell’s time and similar forces at work today. As he wrote in 1944, “The really frightening thing about totalitarianism is not that it commits ‘atrocities’ but that it attacks the concept of objective truth; it claims to control the past as well as the future.”

In 2021, after what feels like years of brain-warping mendacity, I fell upon this sentence with a weird kind of desperation. This bitter kernel, that would-be fascists have to mess with the very fabric of truth, conflating it with its opposite so that it feels impossible to delineate what is factual and what is fabricated, is still pretty hard to swallow.

You feel your soul revolt whenever you get a taste of it, whether it’s from the U.S. Supreme Court pretending that ending access to safe abortion won’t have much effect on the lives of women, or a little closer to home with the NDP’s weak protections for old-growth forests.

One of the book’s most exhilarating and oddly comforting aspects is the way it insinuates the present moment into the past and vice versa. Solnit uses the example of Joseph Stalin to draw a direct line between the methodologies of totalitarian forces then and now and show how little has changed. Lying, subterfuge and fealty to a brutal despot still work pretty much the same way.

A great many people believed (and some still do) that Stalin was a fine fellow, when all evidence to the contrary, like millions of dead Russians, indicates otherwise. Even those who knew better looked away from the truth of his rule. Solnit cites playwright George Bernard Shaw and news writer Walter Duranty as Stalin fans and apologists, but there were plenty of western journalists, writers and artists who also capitulated to the Soviet fantasy.

The chapters dedicated to Stalin’s reign contain some of the most startling characters and historical events. Some are so epic in scale that it’s hard to actually take them in. The U.S. might seem kooky now, but it’s got a long way to go before it rivals Russia for extremity.

For sheer drama alone, Stalin became Orwell’s dark inspiration. As Solnit explains, “For a political writer, the inspiration or at least the prods to write are often repellant and alarming, and opposition is a stimulant. Stalin was surely Orwell’s principal muse, if not as a personality then as the figure at the centre of a terrifying authoritarianism wreathed in lies.”

Ah yes, “wreathed in lies.” That could pertain to a great many people and places at the moment. But back to the U.S.S.R.

As Solnit writes in lucid prose, this active refusal of reality is exactly what took place under Stalin as well as the Soviet leaders who came after, like Vladimir Putin. Other critics have made similar observations about Putin using the lessons of history and adding a contemporary edge to make them even more effective.

But Stalin’s habit of excising former supporters from photos is pretty clumsy next to the Russian bot farms influencing foreign elections via social media today. (If you’d like more on this, simply watch documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis’s masterwork HyperNormalisation).

"Empire of Lies," one of the chapters dedicated to Stalin in Solnit’s book, begins with Orwell attending a lecture in August 1944 given by biologist John A. Baker. In his speech Baker took aim at the plight of scientists in Russia. “When scientific autonomy is lost, a fantastic situation develops; for even with the best will in the world, the political bosses cannot distinguish between the genuine investigator on the one hand and the bluffer and self-advertiser on the other,” he warned.

Baker was referring to two very different men: Trofim Lysenko, the director of the Institute of Genetics at the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Science, and agronomist Nikolai Vavilov. Solnit writes that it is “a story about the triumph of a liar over a truth teller and the immense cost of those lies.” It is a story worth reading closely, as many of the twists and turns beggar description.

In short, Lysenko, a bootlicker and master dissembler, told Stalin exactly what he wanted to hear, namely that it was possible to increase crops yields with hardier strains of wheat almost overnight. The end result of his fiction was the death of millions of people. Whereas Vavilov, who had dedicated his entire career to finding ways of better feeding the world, told the truth and died of starvation in a gulag.

There are proverbs about the mills of the gods grinding slowly, and Solnit notes the work that Vavilov pioneered lives on in the vast quantities of seeds he collected that were protected during the Siege of Leningrad. His followers at the Institute of Plant Industry opted to starve to death rather than eat the seeds and plants that had been entrusted to their care.

What are we to draw from this? Only that history eventually comes around to the idea of justice, that liars are outed, wrongdoing is punished, and integrity and truth are vindicated. But not always.

The lessons of history don’t always pertain exactly, but at best they can remind one that whatever else happens, change is the one constant. Empires rise, empires fall. But before the light returns again, we’re in for a whole lot of suffering.

Still, even in the darkest of timelines, there are things to be treasured, savoured and celebrated. Solnit’s writing is one of those things. Like Orwell, her work shines with the clear light of reason and humanity, reminding readers that this too shall pass, even if it feels like the madness is permanent.

The end section of the book is reserved for a revisitation of Orwell’s most famous book, 1984. Like many great novels, every time you return to it there is something new to be gleaned.

In re-reading, Solnit finds odd flinty pleasures and joyous eruptions of beauty throughout — not only in the obvious places, like the Golden Country of romantic love and sexual passion — but in the figure of a large, red-faced prole who Winston Smith, the story’s protagonist, likens to the rosehip, the mature fruit of the rose plant. There is beauty flung like petals throughout the story, landing in odd places.

In 1984’s penultimate moment, Orwell writes: “Where there is equality there can be sanity. Sooner or later it would happen, strength would change into consciousness.”

Through Orwell, Solnit makes the point that living in the midst of desperate times is nothing new, and that even in the midst of a rising tide of darkness, human goodness endures. Whatever the circumstances, because they always feel impossible, one has to live fully in the face of fear, of corruption, of atrocities being perpetrated. To keep working, writing, planting vegetables and roses and finding ways forward, discovering places of joy and pleasure in this, our one and only world. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: