- The Orwell Tapes

- Locarno Press (2017)

“The very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world. Lies will pass into history.” — George Orwell

We have always needed George Orwell. But now we need him more than ever, as the idea of truth itself is undermined by “fake news,” “alternative facts,” a declining respect for a rule of law based on facts and evidence, and the polarization of political discourse stoked by politicians promising simple solutions to complex problems.

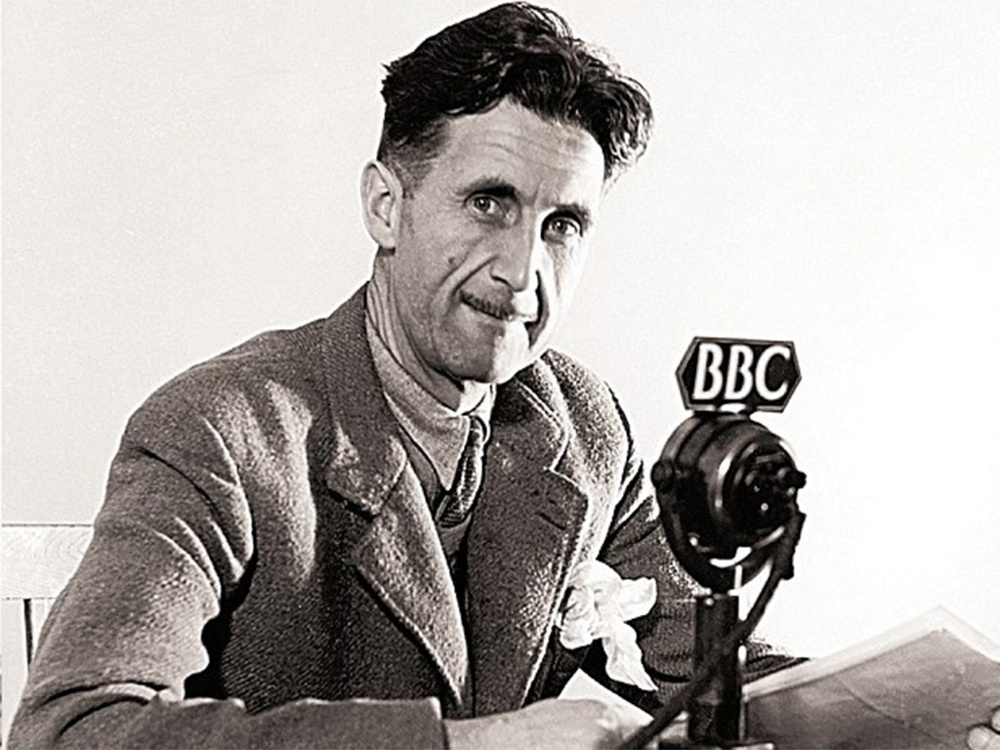

“Two plus two is four,” cried Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four as his torturers tried to make him believe otherwise. Orwell knew very well where the manipulation of truth and the malignant distortion of language can lead. He’d seen it for himself in the Spanish Civil War and even done it himself as a BBC producer in wartime London, matching German propaganda with lies of his own, discovering the seductive power of being freed from normal constraints of truth telling: “One rapidly becomes propaganda minded and develops a cunning one didn’t previously have,” he wrote with perhaps a hint of pride. Orwell wasn’t a saint. He was a political writer, trying to convince. Many of his friends, even his publisher, took him to task for overstating the facts, or oversimplifying them to get his message across. His working definition of truth is intriguing. If what he wrote, he said, was “essentially true,” then it met the test.

Who will guard the guardians?

Not all facts can be easily or reliably checked and almost all are open to interpretation. If truth is flexible then in the end it comes down to trust, the true bedrock of a free society. Trust in the integrity and honesty of the writer and, in the larger arena, trust in leaders and power holders. Delegate but verify. Trust, but keep your eyes open. “Who will guard the guardians?” asked a Roman poet. Who will watch the watchers? The price of liberty, we are reminded, is eternal vigilance. And courage. “If liberty means anything at all,” said Orwell, “it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” It doesn’t get much clearer than that.

Orwell lived in an age of tyranny — Hitler and Stalin — and his greatest fear was that even in countries with a strong democratic tradition people might lose their taste for freedom. Or have it crushed out of them. “Big Brother is watching you” is the most powerful message of his most powerful book, his most potent and prescient warning about the abuse of power.

Imagine if Big Brother had today’s technology. Today if Winston Smith and Julia tried to escape into the woods and fields of the countryside to avoid detection, they’d be spotted by satellite imagery, heat-sensing technology or a drone hovering around the trees. Or betrayed by a small object in a pocket or a purse. “Who here has an iPhone” asked WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, “who here has a Blackberry, who uses Gmail? Well you’re all screwed.”

If a landline is bugged we’d consider it an outrage, yet we seem to accept that in the digital world, our communications can be monitored and hacked. Even in real time, in front of our eyes. Not long ago a British journalist was amazed to find that whenever he typed anything critical of the American National Security Agency and the mass collection of data something strange happened: “The paragraph I had just written began to self-delete, gobbling text. I watched my words vanish.”

“George Orwell warned us of the danger of worldwide mass surveillance,” said Edward Snowden. “A child born today will grow up with no conception of privacy, they’ll never know what it means to have a private moment to themselves, an unrecorded, unanalyzed thought.”

The ultimate goal of the tyrant is self-censorship

“George Orwell saw this massive shift coming,” wrote Orwell biographer Michael Sheldon. Orwell also warned us, he says, that the ultimate goal of the tyrant is not censorship but self-censorship, suppressing and finally eliminating the ability even to think “criminal thoughts.” “Keeping track of what people say and do,” says Sheldon, “is simply preparation for the day when people will banish ‘thoughtcrime’ before it begins.”

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith’s job at the Ministry of Truth was to rewrite history. I have just published a book, The Orwell Tapes, that aims to preserve history in its most raw and potent form. It’s based on a unique archive, 50 hours of interviews with more than 70 people, recordings I made for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1983, as Orwell’s fateful year approached, when it was still possible to capture the memories of people who knew Orwell from his birth in 1903 to his death in 1950. The recordings have led to two major CBC Radio documentaries: “George Orwell, a Radio Biography,” aired on the first day of January 1984, and “The Orwell Tapes,” broadcast in April 2016. And they have led to the book The Orwell Tapes, published this fall.

That summer of 1983, I put five thousand kilometres on a hired car, criss-crossing England and Scotland and making a side trip to Spain in a hectic but fascinating whirl of work. A few people on my list declined to be interviewed, but by August I’d met virtually everyone with interesting firsthand recollections of Orwell. These surviving relatives, friends and acquaintances turned out to be an astonishingly mixed group socially. I was welcomed into homes ranging from a huge and, I was assured, haunted Scottish border house, to small brick row houses in Wigan and Barnsley. I threaded my way along narrow country lanes to find cottages hidden behind high walls and hedges. Even if I arrived late, frustrated and exhausted, my apologies were invariably waved away and I was presented with a calming cup of tea.

A deep love of England

That English summer of 1983 stands out for me not just because of those two fast and furious months on the Orwell hunt. It was more than that. I’d left England and my job as a BBC producer about 10 years earlier for a new life in Canada. Driving through the English back roads, towns and villages, and staying in the modest, comfy, two-star hotels that seemed to be on every high street, at times I actually felt euphoric, consciously in love for the first time with the country where I was born and raised.

Maybe it was the bright sunny summer weather which made the fields look so green, the brick houses so warm and the sky so blue. Maybe it was all that conversation about Orwell’s deep love of England and the English countryside. Maybe it was something that came out of a bottle at the end of a hard day. I really don’t know, but it was a powerful and enjoyable feeling and it caught me by surprise.

The highlight of the trip was Scotland. On the island of Jura, I was taken under the very welcoming wing of Margaret Nelson, who had done the same for Orwell when he showed up “looking very thin and gaunt and worn” in May 1946. Margaret gave me a tour, including the very room where Orwell had written Nineteen Eighty-Four in a race against failing health. This was where I felt sure I’d come as close to Orwell as it was possible to be. I wanted to hear his clacking typewriter, smell his cigarette smoke which must have wafted all through the house. And above all, I wanted to be a fly on the wall observing him writing and re-writing his masterpiece.

Storytelling is all about empathy

If you look at the facsimile edition of Nineteen Eighty-Four, you can see all the handwritten changes he made to the typed draft. They begin immediately, with the opening sentence. Orwell typed, “It was a cold, blowy day in April and a million radios were striking thirteen.” Then he took his pen and changed it to, “It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen.” The first two pages of Nineteen Eighty-Four are a mess of blue ink over black type.

When people die and take their secrets with them, we’re left to guess and infer, to impose our ideas on theirs if we want to make sense of their life and the work they create. What would I give to be able to travel back in time, meet Orwell and ask him why he changed this for that, and how each revision brought him nearer to what he was trying to say.

I’d like to tell him a few things too. For example, how important and inspiring I find his account of crawling close to the enemy trenches in Spain, getting a Fascist soldier in his sights but not being able to pull the trigger because the soldier was holding up his trousers as he ran, which Orwell said turned him instantly from “enemy” into “fellow creature.” It reminds me that storytelling, not to mention life itself, is all about empathy, bridging the gap between yourself and “the other,” resisting prejudging and worse, demonizing people you don’t know but if you did you might like.

The crystal spirit

“But the thing that I saw in your face / No power can disinherit / No bomb that ever burst / Shatters the crystal spirit.”

In Orwell’s poem, the “crystal spirit” was something that he saw for a fleeting but inspiring moment in the eyes of an Italian militiaman he met in Barcelona before going to the front to face Franco’s men. In the eyes of George Woodcock, Orwell’s friend and a long-time resident of Bowen Island, the crystal spirit is Orwell himself.

And for me, who neither knew George Orwell nor has fought in a war? It may sound odd, but the phrase always conjures up the image of a large, beautiful glass chandelier suspended from the high ceiling of an elegant room, slowly revolving in brilliant light. I think it goes back to all those interviews, all the people I met who offered their memories of the man they may have admired or loved but only knew a part of, one facet of the bigger picture. As my chandelier turns, each small piece of mirrored glass gives off its flash of insight into the person who is at the heart of it all.

A rose over Orwell’s grave

On the afternoon of 30 June 1983, I took the train from London to Reading to meet the man who conducted Orwell’s funeral. The Reverend Gordon Dunstan drove us to the tiny medieval church in the village of Sutton Courtenay where as a young man he’d been the vicar. I wanted as far as possible to recreate for the radio the actual funeral service, and Rev. Dunstan didn’t baulk when I asked him to do exactly what he had done that cold day in January 1950, when he had stood in the sanctuary looking out at the coffin that contained Orwell.

Then we went out into the sunshine, to Orwell’s grave. Over the grave, near the headstone, was a spindly rose bush. Rev. Dunstan became a little apologetic; “He asked in fact that it might be left untrimmed, untended, but you know how roses grow, and they become straggly and a nuisance.” So Orwell wanted his rose to spread and grow freely and others decided it should be cut back and controlled. As I stood there in silence for a moment with Rev. Dunstan I thought, “Well that’s how it goes George! Once you’re gone they can do what they like! Everyone wants a piece of you, their own little bit of Orwell.” That’s what I mean about pictures made up of lots of smaller parts like a jigsaw puzzle.

The Orwell Tapes doesn’t attempt to be another biography of Orwell. It’s a collection of memories, nothing more, nothing less, and memory is selective, fallible and often self-serving. I just hope that the sum of all those little personal “Orwells” I recorded in that summer of 1983 adds up to a portrait that Orwell himself would judge to be “essentially true.” ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: