In 1954, Al Parsons wrote about his life behind bars for the prison publication Pen-O-Rama in an essay that could only come from someone living the experience.

“Did you ever go to a circus or a zoo and watch a caged animal pace back and forth, back and forth with quick, short, nervous steps?” he asks. “Did you know that they do that hour after hour? Did you know that, stupid and futile as it is, men do it too? That even you would if you were caged long enough?”

“All the cells in prison have this one thing in common,” his article concludes. “The floors are worn, worn by feet, by the hearts and brains and souls of men who pay their debt to society in a coin that is of no earthly use to anyone.”

Parsons was one of many prisoners who contributed to Pen-O-Rama, which chronicled life in the now-closed St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary outside Montreal.

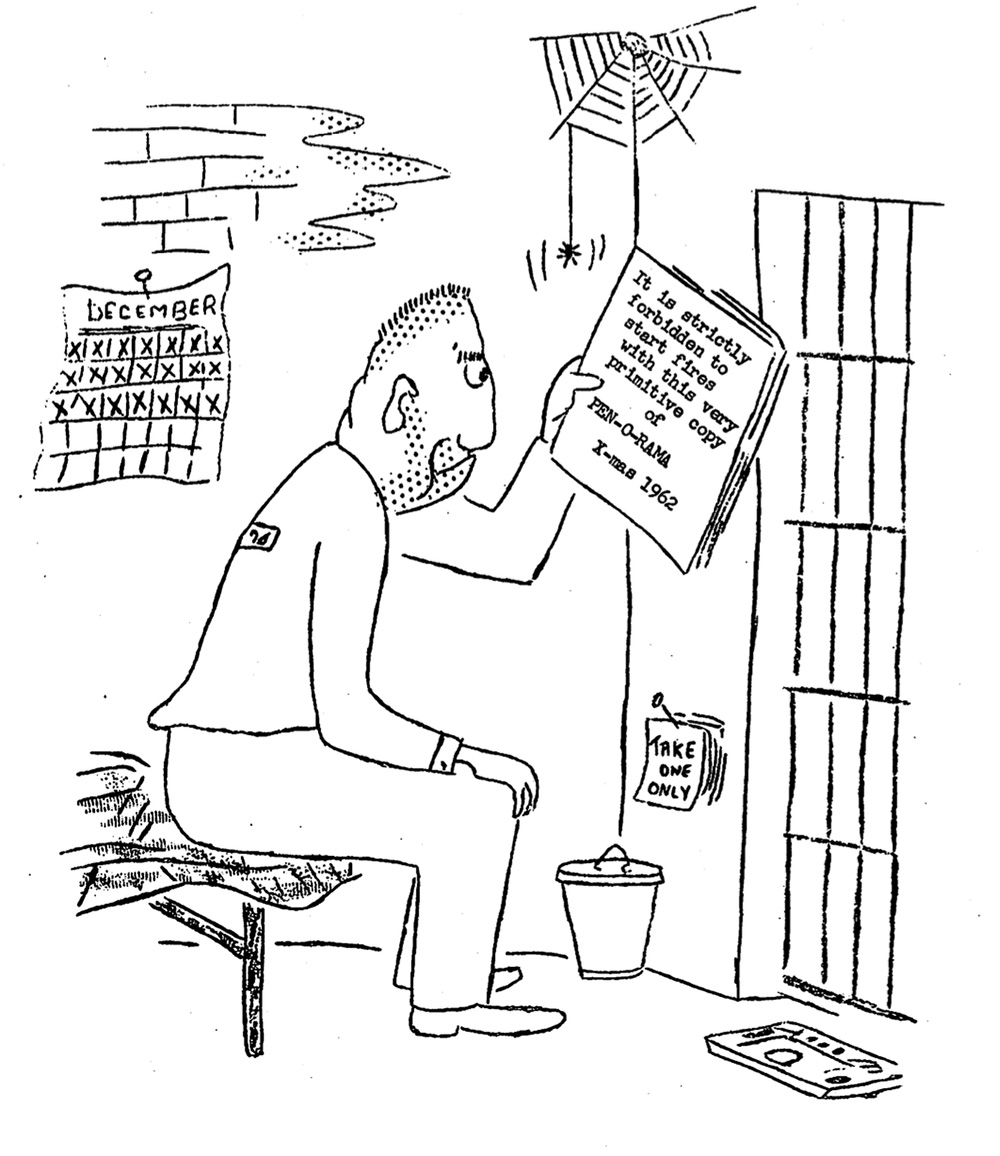

And Pen-O-Rama was just one of many inmate publications across Canada. They were mostly produced on typewriters and roughly copied, but they shared inmates’ stories, poems, drawings and essays, reported on prison sports and other events and generally offered a window into a world most of us won’t see.

Behind them was a flourishing but largely unseen network of content creators, their work documented only in printed copies easily degraded or lost in time.

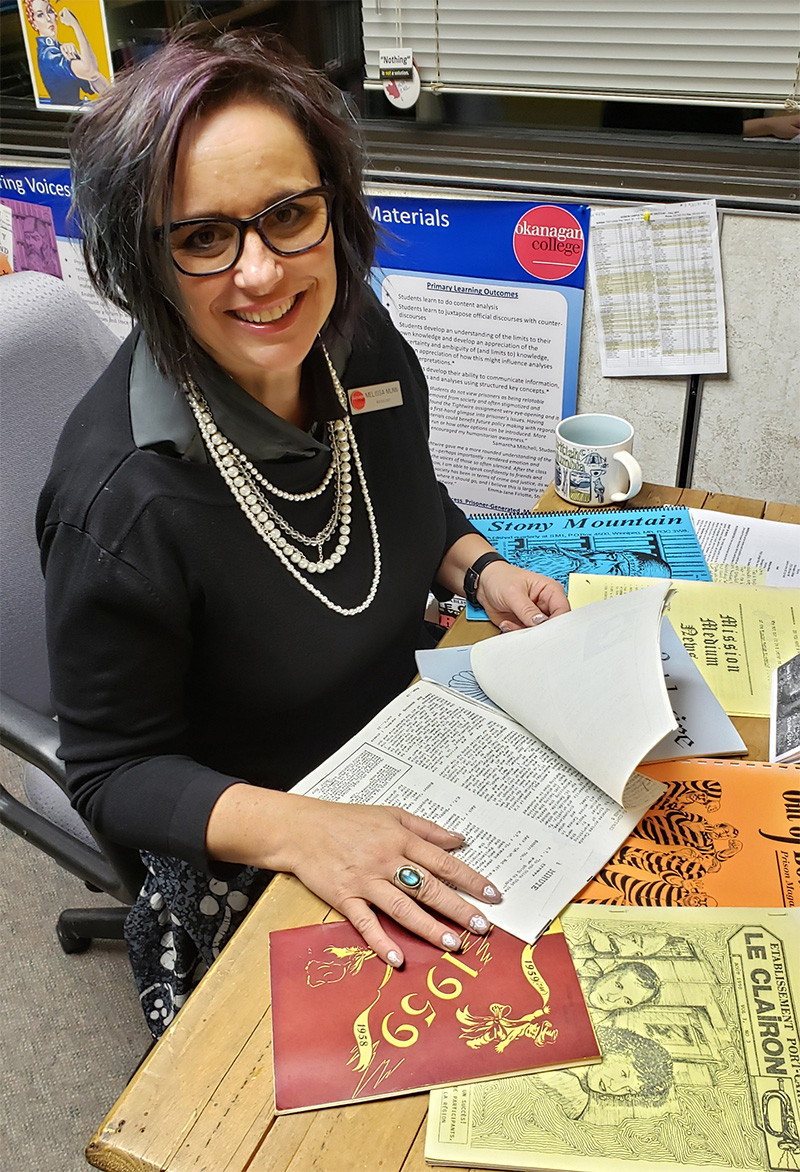

Melissa Munn is working to ensure the work survives. Munn is a professor at Okanagan College with a focus on prisons and their effect on people. A student job helping University of Ottawa criminology Prof. Robert Gaucher copy and catalogue his collection of prisoner publications sparked her interest in the form. When Gaucher retired, she took over his collection.

Now she runs the Penal Press website, home to digitized versions of these rare publications. Munn is also preparing to release a book with Okanagan College history instructor Chris Clarkson about prison publications and prison reform in Canada in the mid-20th century.

As Black Lives Matter and other movements have sparked a critical look at the police and prisons, we asked Munn about the prison press and its role. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: Tell me about the kind of subject matter that tends to come up in prisoner publications across Canada.

Melissa Munn: Historically, the penal press emerged out of sports bulletins, giving sports news. When, in the 1950s, it started to expand, prisoners started talking about things like prison reform, about creating parole systems. In the ’50s, they are talking about reducing and recycling. They are talking about the need for drug courts. They are talking about the need for safe injection sites.

They’re doing all of that in the 1950s. As the press progresses, we see those kinds of themes continue. They continue to talk about prisoner struggles. They continue to talk about rehabilitation. They talk about victims. They talk about drug and alcohol abuse. They talk about politics. They talk about international situations during the war years. They talk about spirituality, Indigenous issues, gender issues, sexuality. From its inception in 1950 right through to the current publications, we see a real diversity of interests and ways of approaching the world, as we see in the mainstream press.

Now, having said that, the penal press is subject to a censorship that does not plague the mainstream press in the same way.

Can you tell me more about that censorship?

Penal press materials are always subject to the censorship of the prison administration, so from its inception that has been a controversy. How much censorship is allowed?

When the penal press was first conceived of by prisoners in Kingston, Ont. — for Canada, anyway — it was perceived as a dialogue between prisoners and their captors. So prisoners were trying to be constructive in their criticism of prison programs, of prison administration. They were trying to suggest that there were problems and there were ways to fix those problems. But of course, when you’re pointing out problems with how prisons are run, prison administrators don’t always like that.

Very early on, and continuing today, there is always pushback from administrators about how much criticism should be allowed. How much of it is constructive? We see this debate raging over what is appropriate, what is reasonable to put in the penal press, what tone should be struck, what is the public entitled to know.

What led to the launch of these publications?

The penal press comes out of a moment in Canadian history when [people involved with prison justice] were looking for what they called the new deal in corrections. They wanted a massive amount of reform in the way that the federal prison system was set up in Canada. They wanted a more humane approach. They wanted a more progressive approach. They wanted a more evidence-based approach.

They really saw the penal press as a mechanism for the new deal, and they thought the penal press would give prisoners the opportunity to have a voice, to engage in constructive criticism that would improve the system. They thought it would give prisoners skills in writing, in editing, in production.

They started it at Kingston Penitentiary, which already had some of the equipment that was needed. The idea very quickly spread across the country. From British Columbia right through to the Maritimes we see prisoners creating, sometimes with very sophisticated equipment and sometimes with old mimeograph machines, and engaging with topics.

One of the great treats of my life was meeting a fellow named André Dion who was one of the first editors of a publication called Pen-O-Rama out of St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in Quebec. He talks about having two typewriters in his prison cell, and if you think about how small a prison cell is and him trying to create this publication out of there, it’s really remarkable.

The impetus came from prisoners and the deputy commissioner of penitentiaries, but also the spirit of the era, this reform impulse that comes out of the Archambault report and this new deal in corrections. It came out of a really hopeful era when people were still very much engaged with the treatment of prisoners. We didn’t have this law and order agenda that has permeated over the past 20 years or more, or this “lock them up and throw away the key” mentality.

The penal press came into existence because people believed that we could do better, that we could use prisons more sparingly, that when we did incarcerate people, we were going to give them opportunities to improve themselves, to get vocational training, educational and life training. This whole idea of rehabilitation was very strong, not just punishment. The penal press starts a very optimistic period in prison history.

What’s changed and what’s the state of the prison press now?

The fundamental difference between the period when the original publications came out and the current situation is that there was a lot of administrative support. There was even financial support for the penal press at its inception because administrators felt it was important to involve the general public in a discussion of prisons. In the ’80s, it was much more about keeping prisons more secretive, not allowing people to know what was going on in them. There was a real tightening of censorship that happened in that period. There was a shift over to risk management ideology and approach, and that made it more difficult for prisoners to step forward with a critique because they were afraid it was going to be held against them.

In the beginning of the press, the editors were celebrated by the administration, so much so that the deputy commissioner took one guy out for dinner while he was on parole and they used to bring the editors over to train the new prison guards. They were given a lot of respect.

I would argue that starting in the ’80s, the prisoners who were involved with the press were seen as rabble rousers, seen as troublemakers, and that was held against them, as opposed to people who were trying to engage in conversation.

Not all prison wardens or prison administrators feel the same way or enact policies in the same way, and this has been a challenge in the penal press. In our book, one of the things we discovered was that prison wardens had different tolerance levels for critique, and so their thoughts of what was appropriate and what wasn’t varied wildly between the institutions.

You can’t really put your finger on a moment in time when the rhetoric changed. It’s this process that slowly undermines the penal press, that slowly makes it more difficult, that slowly convinces prisoners they don’t need it or it’s too risky.

The publications on your website challenge many of the stereotypical assumptions about convicts. Are there any pieces or issues that stick out to you as really spectacular?

I use the penal press with my students, and one of the things that always strikes them is just what you’ve mentioned — how articulate, insightful, thoughtful, considerate the writers are, how they have a unique voice, how through their writing [they are] challenging the dominant discourses on prisoners.

Inevitably, the feedback I get on the penal press website or through the Journal of Prisoners on Prisons is that students come to understand who gets criminalized in a different way. They get to hear a different voice. Inevitably, they’re impressed that this voice exists and shocked that they didn’t know about it. It refutes the dominant images that we are so often fed in the media about who is criminalized and who goes to prison.

I didn’t expect to be as surprised by some of the writing as I was, but there’s a power in the writing of the penal press that is startling sometimes.

The other thing that startles me is how advanced in their thinking prisoners were. In British Columbia in the 1950s, prisoners were talking about safe injection sites as a harm reduction method, and here we are 60 years later having the same discussions and finally kind of getting on the bandwagon. There’s this power in both the content and the style of their writing that comes from their deep experiences in having time to contemplate.

How has interest in the penal press ebbed and flow, and how interested are people now?

When the penal press started there was a tremendous interest in having a subscription. In March 1955 the Collins Bay Diamond was talking about how much they had grown, and said they had 38,000 readers and that half of those held multi-year subscriptions. That’s one publication at a time when there were about eight, and they had almost 40,000 people reading. They were publishing upwards of 4,000 copies of each edition. In the beginning the supporter base grew very quickly and it was very diverse. Prison guards, police officers, dental offices, psychiatric offices and housewives would hold subscriptions.

When the publications first came out, people thought it was only going to be people who had somebody incarcerated in an institution who would be interested, but they discovered pretty quickly that more people were interested. There’s a salaciousness, an interest in what happens in prison that people have, and I’ve certainly found that from using the materials in my own classes. My students are interested in what goes on behind the bars because they don’t get to see it.

Even now that same level of interest is there, but because we don’t have the same number of publications, we don’t have the same promotion of them, there isn’t as much access as there could be. The early penal press sold advertisements to companies like Coca-Cola and Player’s cigarettes and Snap-On tools. They all used to buy ads in the penal press to support them. That became controversial, and that was part of what undermined the press — not being able to sell ads to businesses in the community.

Now the prisoners are paying for it out of their inmate fund in some cases, so the prisoners themselves have to decide if they want to fund it or not, but I do think there’s an interest.

When I look at the analytics on my website, I have a lot of people who are accessing it to read the materials and it’s not a complete site yet. I’m just doing this off the side of my desk, so I upload and code with my research assistants, little bit by little bit. There’s still a lot more to go on there, but people are accessing it.

I get emails all the time from ex-prisoners saying, “Oh, this is great. I wanted to find this article I wrote to show it to someone,” or people who said, “Oh, this is great. I was tracking my family history and found out Uncle Bob had done time and then I found this article about him and it was so cool to hear his own voice.” Other people were doing scholarly research looking at different parts of prison. I think there’s this diverse interest in the penal press and what brings people to want to read it.

What’s the situation now?

Now, we only have two publications that seem to be in regular production. Out of Bounds magazine [from William Head Institution outside Victoria] has three or four editions a year generally. Before COVID, the Mallard [from Mission Medium Security Institution] seemed to be coming out once a month.

Obviously, there are several problems. One is getting content for the magazines. Prisoners don’t have regular access in their federal penitentiaries to the internet, to computers, to computer training, and so it’s quite remarkable that they’re able to put out the quality of content that they do given the huge limitations on what materials can be sent into prison and what materials they can access within prison.

To go back to censorship, the Journal of Prisoners on Prisons, which is an academic, peer-reviewed, scholarly journal, has had trouble getting into prisons. It has been banned from some prisons in Canada. Cell Count, which is a magazine that deals with HIV and AIDS, has had trouble getting into prisons.

It’s very difficult for them to get material, to organize content, to be able to go into production with things because they’re not really given the skills. They’re not given training to do it as opposed to in the past when there was bookbinding, a publishing shop where prisoners got skills in those fields. Now it’s just that somebody gets elected to become the editor, it becomes their job, and they learn on the fly, basically.

How exactly do they design and assemble the newspapers?

When I was at the Out of Bounds office, I was like, “Really? This is what you’re using? This?”

They were actually excited that they had some of their content on CD-ROM, which is why I have had such an enthusiastic response to my website from current and past penal press writers and editors. They see this as an opportunity to make permanent, in some way, the work that they did.

In some of the early penal press I have that was done on mimeograph machines and Gestetner machines, some of the type is so difficult to read because it has just faded out from the erosion of the chemicals. Thank goodness that Robert Gaucher had the foresight to start preserving these materials. Without his foresight, they would have just been lost to us.

What can be done now to support the penal press?

If more institutions were encouraging, that would significantly help with the growth of the penal press. I think it would give prisoners skills. I think it would improve their self-esteem, and that’s always good for reintegration, for people to feel that they’ve had the opportunity to participate as a citizen in the press. It would give the public a better sense of what’s happening in prisons, maybe build support for people who would like to do really interesting, innovative initiatives who don’t feel they can get the support.

If there was some funding allotted to it, if there was some training allotted to it, if the institutions themselves were more interested, I actually think there could be room for a national prisoners’ press so each institution gets to submit a page and it comes out quarterly.

I think it’s going to require the system to see the penal press as an instrument of positivity, an instrument of best practices.

Why do you think we should be paying attention to the penal press now, as intersecting crises like COVID-19 and police brutality influence public perception?

I think it is always important to attend to the lived experience and that is what the penal press does. As Black Lives Matter has demonstrated so effectively, the official state discourse and rhetoric does not always represent what is really going on, how things are being experienced. In contemporary society, we have people videoing what is happening, and this has lent credibility to the claims the disadvantaged and disenfranchised have been making for decades.

Clearly, prisoners don’t have the advantage of running video cameras. People are not allowed behind the prison walls. The penal press has been one of the only mechanisms to express and document their experiences. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: