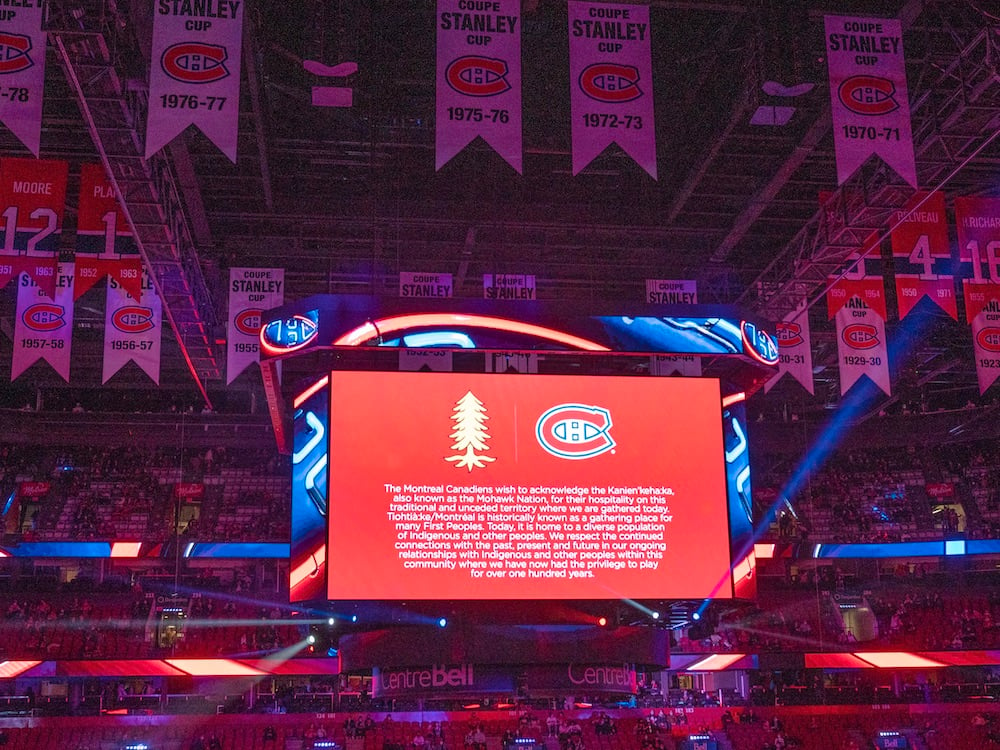

Today, land acknowledgements often show up at the beginning of most events, the bottom of many webpages and email signatures, and in “about us” sections.

They usually go a little something like this: “Insert organization here would like to acknowledge that we are on the traditional and unceded lands of the names of local nations, whose relationship with this land continues to this day.” (You can read The Tyee’s on the website’s contact page, under “Acknowledgements,” for example.)

Land acknowledgements, also known as territory acknowledgements, can be used as an act of decolonization, by naming Indigenous nations, recognizing their traditional lands and stating that these lands were taken in colonization.

They can be a way for organizations, people and places to recognize and encourage the remembrance and research into Canada’s history of colonization. They can even signal the support of the organization or person to return Indigenous sovereignty to these lands.

But land acknowledgements can also become performative in nature — what starts as an act of support can quickly become just another checkmark to tick on the “things to do” column.

Are there ways to make such acknowledgements more meaningful? What is the difference between a “land acknowledgement” and a “territory acknowledgement”? And how do Indigenous people feel about the practice? Those are some questions I’ve set out to explore in this article. (A note: this article explores several perspectives, but does not reflect the views or opinions of all Indigenous peoples — no single article could.)

The history of land acknowledgements

Land acknowledgements are a practice used in some Indigenous cultures to recognize other nations’ homelands. They’ve been adapted to fit a mainstream purpose.

They have risen in popularity since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action came out in 2015. While the calls to action don’t directly address the need for land acknowledgements, they’ve become common as a show of support and as a decolonizing action in the wake of the TRC.

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls also found that responsibility, accountability and acknowledgement are important and necessary to promote further change in Canada.

The City of Vancouver first recognized that Vancouver was on unceded lands via land acknowledgement in 2014. Similarly, the City of Toronto began implementing land acknowledgements in 2014; the language was most recently updated in 2019, after discussion with their Aboriginal Advisory Committee.

The City of Montreal notes that their “historical steps” towards reconciliation started in 2017 — but land acknowledgements aren’t listed as one of the steps they utilize. The City of Ottawa created a formal action plan for reconciliation in 2018, stipulating they would: “promote a standard process to honour Algonquin Unceded Territory at the opening of city events.”

How land and territory acknowledgements differ

“Land acknowledgement” and “territory acknowledgement” are used interchangeably nowadays. But their connotations are slightly different: “territory” tends to make people think more about things like jurisdiction and governmental authority.

Your Syilx Sisters, a communications company founded this year by sisters Lauren Marchand and Kelsie Kilawna (Marchand), who are members of nk̓maplqs, or the Okanagan Indian Band, leans away from the term “territory.”

“‘Territory’ always makes everything sound like it needs to be a fight,” Kilawna says. “There's territorial conflict, all those things.”

Kilawna says “territory” also ties a land claim to a specific nation, when nations lands can and often do overlap.

“Land acknowledgements,” she adds, “honour the place where you are. Because in a lot of places we have shared lands with other nations that are neighbouring.”

Through Your Syilx Sisters, Marchand and Kilawna use their Syilx teachings to advise people and organizations about a range of different communications questions, including consulting on land acknowledgements. Before they work with anyone, however, they conduct a meeting to discuss protocols and intentions.

If the work isn’t going to be “honoured, upheld and continued” after their collaboration concludes with the company or person, they will choose not to work with them. This ensures, they say, that the process is not extractive, that they are not tokenized and that the work that follows is not performative in nature.

An integral part of this work involves teaching clients to self-locate, by asking some very serious grounding questions, such as “How do we locate ourselves in the history of who we are, as in our bloodlines? How did our bloodlines actually bring us to this space? How did I benefit from the oppression of you?” Kilawna says.

This self-location prepares their clients to write land acknowledgements from “an authentic place” that is deep and meaningful, says Kilawna.

Avoiding ‘cookie cutter’ acknowledgements

When done right, land acknowledgements can be a meaningful act of reconciliation.

This means taking the time to self-locate, rather than seeking out a cookie cutter template to adapt for one’s own purposes.

It can also mean recognizing that land acknowledgements by themselves are not enough.

Marchand and Kilawna stress that it is also important to connect with local nations, participate in education about culture and colonialism, and find ways to move forward. Without meaningful actions like these, land acknowledgements will seem performative in nature.

Another way to look at it is that land acknowledgements are the bare minimum, says Marchand.

“I think they have their place, when done appropriately,” she adds.

‘Honouring the land’

So now you are up to speed on some of the history and nuances of land acknowledgements as practiced today. But how do Indigenous peoples feel about them? And how do they relate to reconciliation and decolonization — or do they relate meaningfully at all?

Ta7taliya-men Paisley Nahanee, from Squamish First Nation, is a workshop facilitator for Nahanee Creative Inc., a DJ and an event producer for the Indigenous dance party Hotlatch.

“I think [land acknowledgements are] a really important beginning step on someone’s decolonizing journey,” she says.

As a workshop facilitator, Nahanee says she often sees people in denial that Indigenous lands were stolen. Seeing people progress and begin to use land acknowledgements, she says, is a good first step.

The next step, she says, is to learn more about place names, nations and the land itself. “That’s where some really cool shifting can happen,” she says.

Nahanee is happy to see land acknowledgements becoming the norm in event spaces.

“Those weren’t happening, you know like, five years ago! It took... some really radical people to start doing it,” she says. “Now, they’re more of a norm and I think that’s really excellent.”

“I see it as an honouring,” she adds. “You’re honouring the land, honouring the importance or value of the land.”

Nahanee encourages people to consider what further practices they can do to help reconciliation and decolonization, and build relationships with Indigenous peoples after they practice land acknowledgements.

The act of land acknowledgements might not be the “most meaningful thing,” she says, but it helps promote change in some people, even if it doesn’t change everyone.

Nahanee also notes the progress Canada has made when it comes to land acknowledgements and noting Indigenous peoples — and how quickly this change happened. “I’ve had friends... visit me from the States where there’s a land acknowledgement... and they’re like: ‘We’ve never heard that back home!’” she says.

“That helped changed my perspective as well... there is a movement that is happening.”

‘It depends on who's speaking and who's saying them’

Belinda Daniels, a member of Sturgeon Lake First Nation, is a teacher and a professor with a PhD in Indigenous language.

Without meaningful action, she feels, land acknowledgements are often performative.

“How I feel about land acknowledgments? I think it depends on who's speaking and who's saying them,” she says.

“If it's the colonial settler, acknowledging the land that they're upon,” she says, “sometimes I feel like they're an empty gesture. While at the same time, I think it's a beginning of something, maybe it's the beginning of something more to hope for.”

Her preference to see change within the mainstream practice of land acknowledgements includes learning how to acknowledge the nations within the language of the land.

“I want them to say it like they mean it,” she adds.

“Also, when people are acknowledging land and doing the land acknowledgments, maybe practice saying the nation's names correctly.

“More often than not, I hear again, settlers mispronouncing nation names.”

Daniels encourages those who are non-Indigenous to become involved with relationship building with the local nations.

Daniels also prefers the term “territory acknowledgement.”

“Territory seems like more of a shared concept,” she says. “Like we have Treaty Six Territory. Do you know how many nations are within Treaty Six Territory? There's quite a bit.”

“When it came to like historical partnerships like the Cree and the Blackfoot and the Dene,” she added, “[they] shared the same territories but at different seasonal times.”

‘Land acknowledgments can be highly problematic’

Kolin Sutherland-Wilson is a Gitxsan member and a household name when it comes to Indigenous rights, Land Back advocacy and protesting.

He takes issue with lawmakers who perform land acknowledgments — and then turn around and say Indigenous rights do not matter.

“[It’s like] your title to this land has been extinguished by the Crown for this reason. Or we cannot recognize your jurisdiction for this reason,” Sutherland-Wilson explains. “Or simply that you've been so assimilated, that you don't have any of your original rights that come through your governance.”

“So, you know, within that context, I think land acknowledgments can be highly problematic.”

These acknowledgements, he continues, are “a way to address that agency within colonization and genocide and without actually having to provide any redress.”

“There needs to be strategy,” he says.

Sutherland-Wilson says he would like to see real movement on issues surrounding land governance, and hostility towards Indigenous land governments within the court system.

“I always think of the old analogy of a simple bicycle. Or as someone explained to me, OK, like if I stole your bike, and then told you later that I was sorry for stealing it, that acknowledges that it’s your bike but I never gave the bike back to you,” he says.

“It's not truly an apology. It’s not truly redress. What does it solve in that situation? For some folks, it might even be considered a bit of an insult on top of the original action.”

“The fact of the matter is, we still face a Canadian society that is aggressively trying to undermine the very thing they're acknowledging,” he concludes.

“The fight continues on.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: