[Editor’s note: Under the White Gaze originally ran as an exclusive Tyee email newsletter last fall. We’re republishing the full series of essays on our site this month. This essay, the sixth in the series, was originally titled 'Condescending Tropes that Canadian Foodies Must Try!']

All my life I’ve been spoiled by Vancouver’s Asian restaurants, eating everything from congee to chana masala. But just as exciting to me growing up was reading the newspaper clippings that hung on their walls — carefully cut out and proudly displayed in huge frames by the owners, like something sacred.

These were precious documents, yellowed with age, that said that these places mattered. Someone came down from on high and wrote a review that gave the wontons, laksa and pakoras their blessing, and brought the foodies on pilgrimages in droves.

It was rare seeing Asian faces in the news back then, even in Vancouver, so it was all the more thrilling to read the coverage.

I remember waiting in line at Chinatown’s Phnom Penh restaurant and reading the visceral story of the owners hanging from the wall, told in the Vancouver Sun.

The family behind the restaurant shared how they hid in the Cambodian jungle for a month before crossing over to Vietnam, where they sold noodles on the street. The story included details about gold and smugglers, a jailed son and benevolent Canada welcoming the family with open arms. Oh, and garlic squid.

The Sun featured the restaurant numerous times, with one writer calling its dishes “real food... the smell of holiness.”

True, the writing could be sentimental, and often featured a jarring blend of suffering with deliciousness. But as someone from an immigrant family, I got sucked into the storytelling — tales of sacrifice, tastes from the homeland and multicultural Canada coming together at the dinner table.

You might think that coverage of restaurants in Vancouver and other multicultural Canadian cities is devoid of the white gaze because there’s so much food diversity.

Yes, that diversity is celebrated, but these eats are still held at a distance.

Just think of how “ethnic” food is described locally.

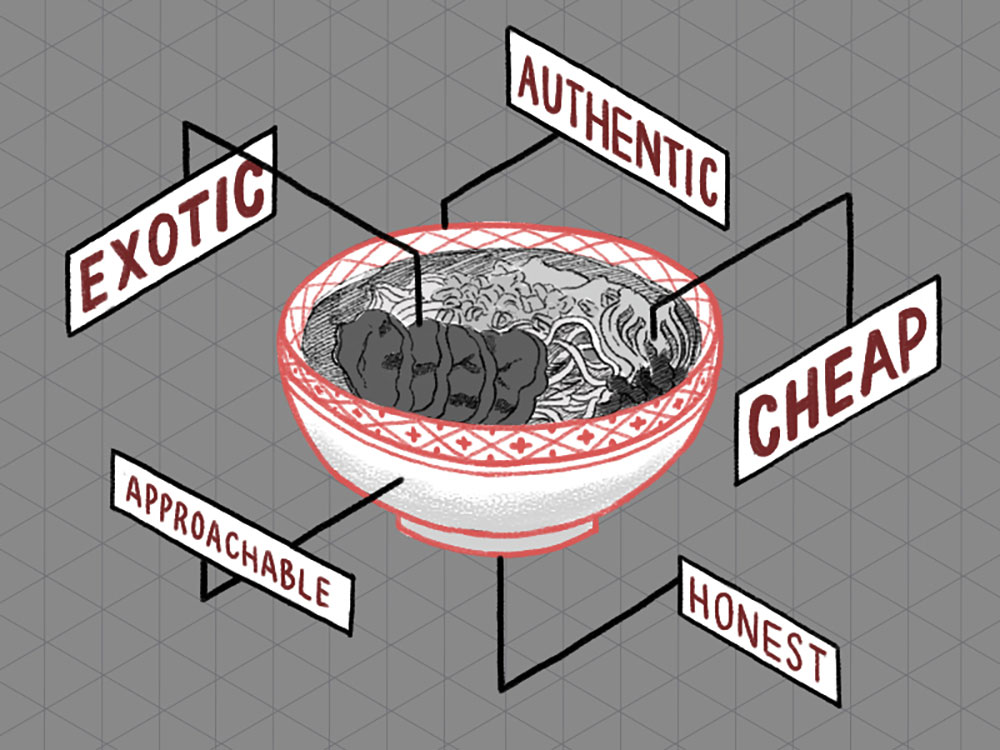

Fish balls as “exotic.” Ancient eats like congee as “new.” Writers decide which dishes are “serious” and “authentic.” They may praise a restaurant for making a cuisine like Vietnamese more “approachable.”

But exotic to who? New to who? Authentic to who? Approachable to who?

“Within commodity culture, ethnicity becomes spice.”

That’s a quote from bell hooks, the American scholar and activist, in her classic essay “Eating the Other.”

“The commodification of Otherness has been so successful because it is offered as a new delight,” hooks says, “more intense, more satisfying than normal ways of doing and feeling.”

As a result, Phnom Penh’s cuisine, originating in the jungle and enduring the fire of a refugee journey, is described as “real food.”

Ah, the hunger for status and distinction in culinary adventuring! The more exotically you eat, the more experienced you are.

Not all foodies are white, but all foodies can be capable of othering racialized people and their food. And in Canada, Eurocentric foods tend to be the baseline by which all other cuisines are measured. It is from this baseline that foodies hunt for “new” food experiences, and emphasize the crossing of boundaries into the world of the other.

There are plenty of local examples of “othering” to jab at.

This guide to dim sum apologizes for the “problem” textures of dishes like chicken feet. This review of a soba shop has a 175-word opening on the author’s experience with Japanese (“its unique phrasing and compound alphabet results in a mesmerizingly lyrical system of communication”).

Crueler analysts than me would have a field day tearing up write-ups like these.

But I’m more interested in how the white gaze on food considers people and place, class and consumption. So let’s move on.

Food media loves their expeditions into the 'hole-in-the-wall.'

I get it, there’s the street cred of surfacing a “hidden gem” to audiences.

An off-the-beaten-path greasy spoon is more exciting than a French restaurant, giving well-to-do audiences the experience of traversing into a gritty, blue-collar world that serves “honest” food that is “surprisingly” delicious.

But an off-the-beaten-path dumpling stall, perhaps in the belly of some suburban Taiwanese mall where aunties make them by hand, is even better.

Disclaimers like “intimidating” and for “adventurous eaters” are often used.

But bear with it and enjoy the reward of cheap ethnic food, with prices “far lower than what you would pay in the grocery stores or your local Blenz,” says the Georgia Straight.

As hooks writes, “Encounters with Otherness are clearly marked as more exciting, more intense, and more threatening. The lure is the combination of pleasure and danger.”

Sure, hole-in-the-wall can refer to the physical location. Indeed, a lot of them are small joints, perhaps located in the inner city, with sparse or seemingly random décor.

But they may also be holes-in-the-wall in the imagination of the outsider. Who cares if it’s on a major thoroughfare? It’s a hole-in-the-wall because it serves “foreign” cuisine.

It doesn’t matter if every Canadian with Cantonese roots knows of this barbecue shop — foodies with ethnocentric palates emphasize the everyday as exotic and sell cornerstones as hidden gems.

There are writers who put-down these places while praising them at the same time, stoking their status as explorers with a penchant for risk.

The Northern Café, which is above a hardware store in industrial South Vancouver, has been described so many times as a hole-in-the-wall that I’m not even sure it qualifies as one anymore.

It’s a diner run by a Chinese Canadian family, and it’s been written about by everyone from the National Post to the Daily Hive to countless food Instagrammers, as if they’ve found the El Dorado of bacon and eggs.

Here’s the language used by the National Post. “Prepare to be staggered: by the uneven floor.” “Visual confusion.” “Random drawings.” “Funhouse at a summer fair.” “Canada’s... most rundown restaurant.” “The best of the oldest, most decrepit eateries in the land.”

Restaurants are stripped down to objects of discovery and consumption in these reviews.

What’s missing? The fact that so-called holes-in-the-wall are often run by migrants in Canada who don’t exist to chase Michelin stars — rather, to make ends meet and serve their clientele cuisine they need.

Food writers have also weighed in on critiques of racialized places as they gentrify.

University of Toronto sociologist Zachary Hyde noted this phenomenon in a paper analyzing 296 Vancouver restaurant reviews.

Hyde points to a New York Times review of the lauded Japanese-Italian restaurant Kissa Tanto. The writer says that the fancy restaurant in Vancouver’s gentrifying Chinatown “inhabits the neighbourhood respectfully.”

Commentary like this can be found in other reviews of hip new eateries in Chinatown.

The Vancouver Sun reviewed a café-grocery called Dalina in a new condo building. The writer wrote that she’s “happy to see millennials in this habitat,” “with laptops and beards,” “as it speaks to their resilience in this unaffordable city.”

The Globe and Mail reviewed the Union, which the writer calls a “photo-box” in a “desolate wasteland.” The clientele, she says, are a “panoramic snapshot of urban diversity,” which includes “surfer dudes” and “architect types.”

These reviews nod to Chinatown’s troubles — an immigrant community trying to reinvent itself amidst urban decline and gentrification — yet praise espresso-sipping millennials on laptops and brave surfers for their willingness to visit this “wasteland.”

Next time food media invites you to eat in some racialized neighbourhood, see whether the narrative of cool eats making an area better is actually erasing local life and struggle — taste determining who and what fits in a place.

When it comes to “eating the other,” there is constant tension between two impulses.

Is it for status? Or does it come from a genuine desire to experience another culture?

University of Toronto sociologists Josée Johnston and Shyon Baumann talk about this in their eye-opening book Foodies.

In many of the reviews I’ve seen on restaurant walls over the years, there’s a mix of both these impulses.

The otherness of the cuisine is stoked, sometimes in Orientalist ways, just as it is celebrated — I admit I’ve written pieces in this vein myself, and at least two of them are still on the walls of Vancouver restaurants.

The white gaze in food journalism is no different than its presence in any kind of journalism, subjecting people, places and cultures to the same judgments and stereotypes.

But to the mom-and-pops making a living, reviews can mean a lot, regardless of what the representation looks like.

Sure, Canada has a lot of multicultural menus, and we’ll always be eating dishes that are new to us.

But just because food media feature racialized people and their cuisines doesn’t mean representation is guaranteed.

Is the menu “cheap,” or is it that it caters to the budgets of working-class customers?

Is a food court stall reluctant to give extra chopsticks because the owner is “rude,” or because she’s careful about their budget?

Is a restaurant serving “approachable and aesthetically pleasing” foreign food because it used to be scary and ugly? Or because Canadians with Eurocentric palates aren’t used to flavours and ingredients common to another culture?

Is a hole-in-the-wall in an odd, faraway location for white urbanites because migrants are intentionally trying to be mysterious? Or because commercial real estate in a central location with foot traffic is expensive and outside of what new Canadians can afford?

Shallow coverage feeds us imagery of how rundown a restaurant is to emphasize adventure, and imagery of ethnic crowds packing into a place to emphasize authenticity. Class and culture are just visible enough to be delicious, yet invisible in the way of more nutritious understanding.

The richest coverage doesn’t just lead audiences to food. It shows how that food got to us — and what it means to the chefs and the community in which it’s served.

Discussion questions

- Food adventurism is everywhere. How do we balance exploration with respect?

- What are some foods that you’ve seen “othered” in media?

Readers’ corner

Can’t help but share this joke tweet by @deshumemusic that our readers shared with us: “white vancouverites take the #20 past Kingsway and think they’re Anthony bourdain.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: