[Editor’s note: Under the White Gaze originally ran as an exclusive Tyee email newsletter last fall. We’re republishing the full series of essays on our site this month. This essay, the first in the series, was originally titled 'Don’t Look at Me Like That!']

Tyee reporter Christopher Cheung here to share with you my big journalism fear.

My name might be Christopher, but I worry about being a kind of Columbus.

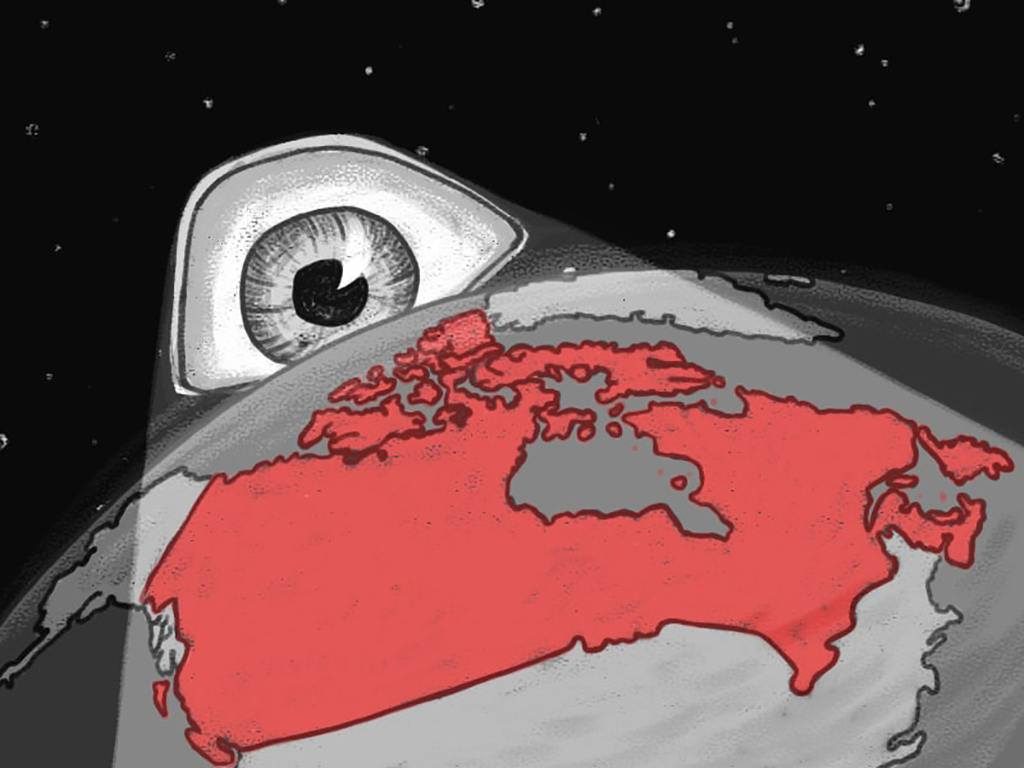

It’s easy to fall into that trap. Our profession demands that we find fresh stories that grab eyeballs. And sometimes, in service to “average Canadian” readers, we end up introducing them to people and places through the lens of an outsider — or worse, a colonizing power.

I found an old story of mine where I said that a neighbourhood — a landing place for immigrant residents for decades, from Poland to the Philippines — wasn’t “established” until an artisanal ice cream shop moved in. Eek! Columbus alert: assuming a place is a jungle until someone from the outside world discovers it.

In another story on an Indian restaurant with vast offerings, I led with the boring, stereotypical description of a “smell of hot curry and spices.” Ah! Way to flatten a huge country’s food, Chris.

Just yesterday, I wrote the phrase “mainstream Canadians” with white Canadians in mind. Does that imply that everyone else is a weird outsider?

I started to wonder: why was I looking at the world in this way?

When I entered journalism seven years ago, it seemed like an optimistic time for diversity and inclusion.

Newsrooms were keen to show that they served all people by hiring new writers and publishing more coverage of underrepresented groups.

My friends and I, Canadianborns of immigrant parents, have craved more representative journalism all our lives. When I entered the profession, I proudly wrote about various Vancouver neighbourhoods that didn’t get a lot of media attention, to show what they’re really like.

But over time I noticed that some journalists, when writing about our city’s diversity, would fall into a common way of looking at the world, just as I did. I had trouble describing the specifics of this gaze, but I knew its effects:

Stories that treated groups like “Asians” in a homogenous way.

Stories featuring immigrant seniors, quoting them saying things like, “I like to make the friendship.”

Stories on cultural holidays, homing in on the most exotic aspects and their most ancient history. Dragon dancing! People jumping over fire! Hm, but where’s the coverage the other 364 days of the year?

Non-white characters in news stories are sometimes portrayed in this old-world, Orientalist, National Geographic way, as if they’re all harmonious people, part of homogenous tribes, dedicated to inscrutable traditions. A bit like the stereotype of the “noble savage.”

We journalists are very much dedicated to objectivity as a pillar of our profession. So how do these examples of dehumanization creep in?

Media scholars have a term: the “view from nowhere.”

Many journalists strive to report from it, to present information that’s fact-based, neutral and balanced.

As I started my career, I had trouble reconciling this view. Don’t we make every choice in our reporting? What stories to tell, who to quote and even which quotes are included?

As it turns out, I wasn’t the only one who thought it impossible for people to do journalism without a “view from somewhere.”

“No matter how far it pulls back, the camera is still occupying a position,” media scholar Jay Rosen once said.

“We can’t actually take the ’view from nowhere,’ but this doesn’t mean that objectivity is a lie or an illusion. Our ability to step back and the fact that there are limits to it — both are real. And realism demands that we acknowledge both.”

Crack open any news story, and you’ll find three perspectives that shape how it’s presented: the author, the audience, the actors.

The author decides what to show and share.

The audience is who the story is catered to, from the topic chosen to the context included for their benefit.

The actors have their appearance shaped by the author, from what they do to what they say.

These three perspectives can work very well together. A smart author will deliver to the audience exactly what they need to know, and present what actors say with big-picture context.

But imagine if the author has internalized a white gaze and is writing for a white audience about people who aren’t white.

If the author doesn’t do their homework, it’s easy for the coverage to be infused with ethnocentrism.

We get stories where people who aren’t white are viewed as “ethnic.”

We get stories where foods like sandwiches are described as normal, while others like hummus are pegged as exotic.

We get stories about Indigenous people with a relentless focus on “disaster coverage” and little else from within their communities.

We get stories aplenty about European heritage since contact, but very little about the millennia of Indigenous history before that.

We get stories that say neighbourhoods are “emerging” when new condos or chic restaurants show up, never mind the immigrant families who’ve called them home for decades.

We get stories about racialized people who aren’t interviewed for the story at all, instead privileging the voices of white characters talking about them.

We get simplistic tropes recycled again and again: the good Indian, the model minority, the bad immigrant, the damaged newcomer, the perpetual foreigner.

If that’s all the coverage there is, isn’t it obvious that the audience would begin to form stereotypical impressions about these people?

Many great minds have pondered the concept of gazes — from Jean-Paul Sartre to Toni Morrison, who coined the term “white gaze” — and used the idea to understand how powerful parties consider others in the world.

Think of the privileged gaze common in reporting on poverty, with journalists highlighting crime and decrepitude, accompanied by photos of needles in puddles.

Think of the male gaze common in cinema, with filmmakers sexualizing women whose only role is to accompany heterosexual male characters and please the hetero male audience.

These gazes determine what we see and how we see it.

We happen to live in a country with Anglo colonial roots, and our most spoken official language is English. Is it really a surprise that our news media takes a white perspective for white audiences when reporting on Indigenous people or “ethnic communities”?

Even the term “ethnic” is a product of the white gaze, assuming that being white is the baseline by which all other people and cultures are measured.

Real representation in news media is about more than just “visible minorities” seeing faces like us on a page or on the screen. It’s about everyone seeing people like us as part of society.

Disclaimer: I’m not trying to solve racism, life, the universe and everything.

I’m trying to investigate the roadblocks to do with race and representation that I keep running into during my reporting.

I just used the term “visible minorities,” but what to do with loaded language like it? How to introduce cultures to English readers with sensitivity and accuracy? How to convince people not used to sharing their story that their voices matter? And of course, what to do when white readers belittle stories that mention race, and say that we should be focusing on the “real” crises like climate change and runaway capitalism instead?

Readers have told me proudly that they “don’t see race” and that I shouldn’t waste my time writing about it. Well, if they don’t see race, no wonder they don’t see that racism exists, and how it’s intertwined with other crises. Just look at our unequal pandemic. Racism won’t go away just because some of us cover our eyes.

“The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist,” poet Charles Baudelaire once said.

It’s the same with racism and privilege. Advantaged or disadvantaged, we all play a role. And it takes some tough introspection to see this.

Hey, I’m not white, and I barely noticed that I internalized the white gaze myself.

So has my mom.

When I was a kid, I took a bite out of a sesame ball and asked what the sweet paste inside was. It was red bean, but my mom, hoping to relate to Canadianized young me, told me it was “Chinese chocolate.”

Ahh, the white gaze, and its ability to erase cultural knowledge of desserts!

More seriously though, this incident taught me that information is shaped by who’s doing the presenting and who’s being presented to. That’s an enormous power.

By the time you finish reading the articles in this series, I hope you’ll learn to catch the distorting effect of the white gaze in Canadian news media, and how journalists can strive for representative reporting that encourages equality.

We at The Tyee first published this series as a newsletter, subscribed to by over 5,000 people, whom we invited to ponder discussion questions and offer us their thoughts. We’ll be including some of those along the way. Thanks for joining this journey.

Discussion questions

- How have you seen the white gaze at work in the journalism that you consume?

- Has news media ever led you to form stereotypes about people, places or cultures?

- Have you ever had journalism misrepresent the place or culture you’re from?

Reader’s corner

Ken McFarlan: “I’ll start by saying I’m white — and male. I wake up white, can urinate while standing up and I never give it another thought in my day having to assess whether I’m being treated as ‘less than’ or have a multitude of assumptions/observations made about me that have the potential for any interaction to become stressful or cause for anxiety. I cannot say you’ve chosen an easy assignment, but I look forward to hearing your thoughts and perspectives. If you nudge the needle a bit into the territory of people examining their language to be inclusive and welcoming to every reader, then that will be a good thing.” ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: