[Editor’s note: Under the White Gaze originally ran as an exclusive Tyee email newsletter last fall. We’re republishing the full series of essays on our site this month. This essay, the fifth in the series, was originally titled 'Ethnically Diverse Man Gets Tongue Tied.']

One of the most agonizing parts of my job is choosing the right words.

I know. A journalist, struggling to find the right words? Isn’t that the job?

But when reporting on racialized people, the wrong words can do serious harm, leading readers to fall into inaccurate, even negative, stereotypes.

Talk about culture without context, and people might seem primitive. Talk about migration without context, and people might seem like a faceless tsunami.

Finding the right words can be an exhausting game of mental chess — especially when the reputation of a character is in a journalist’s hands, not to mention representation of underrepresented people at large.

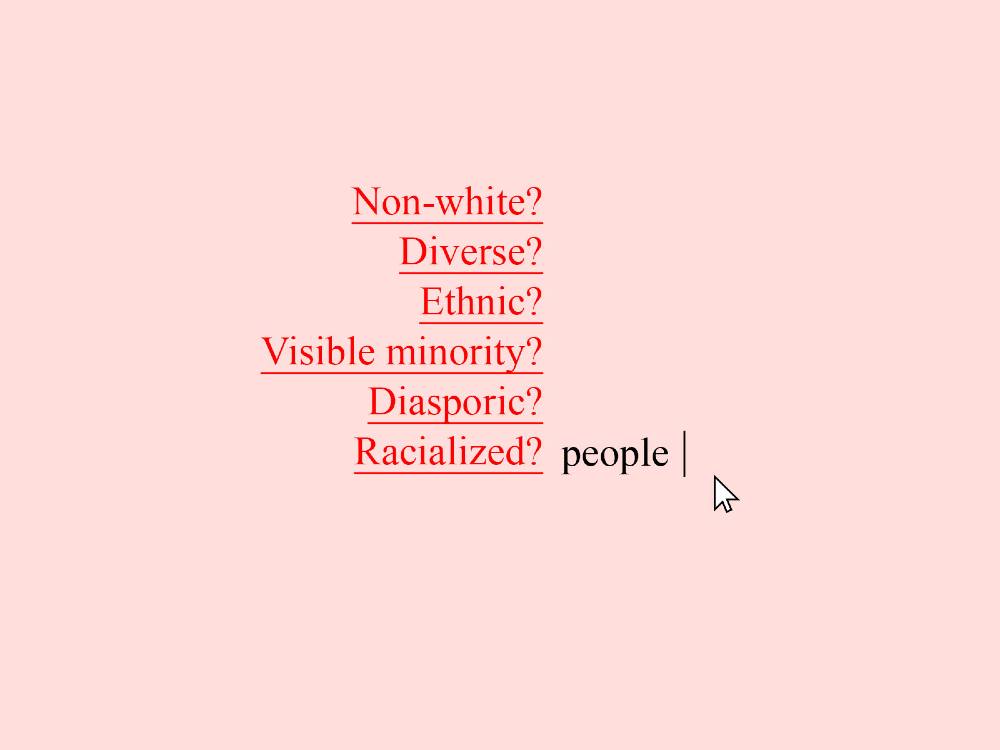

Let’s start with a basic but common challenge. I don’t even know how to collectively describe the people I write about who aren’t white.

“Non-white” doesn’t work. It’s disempowering, based on being not something.

“Diverse” doesn’t work. Why do white people get to be normal, and everyone else diverse? White people are diverse too.

“Ethnic” poses the same problem. The Vancouver Police Department likes using it to boast of its “ethnically diverse officers.” What does that make everyone else?

“Visible minorities” has persisted, because it’s used as a legal definition and by federal agencies like Statistics Canada.

But it feels like a perpetual label of foreignness and marginalization. Not to mention it becomes totally incorrect in places where so-called minorities are the majority.

“Racialized,” “marginalized” and “underrepresented” might work in stories about discrimination. But as a label, who wants to be identified as a victim?

“People of colour” and “BIPOC” have become popular, but they flatten groups into one category, and carry the baggage of the offensive phrase “coloured.”

See how hard it is to find the right words?

Take “ethnic enclave.” The term comes from sociology, used to describe an area where people of a shared ethnocultural background live and work in large numbers for support and to avoid discrimination. Commenters tend to flock to the stories I write about enclaves to complain about the people living in them being un-Canadian about their self-segregation.

The word “community” often doesn’t work either. “Ethnic community,” “Muslim community” — what could be vaguer? “Community” can ignore difference and make the people in them sound like part of a hive mind. It also makes it seem segregated from larger society.

Pointing out that a character speaks “no English” is a weird little shortcut used by journalists, highlighting their lack of ability. It’s worse if there’s no mention of the languages they do speak.

When a story says a character speaks “not a word of English” or has “zero knowledge of the English language,” you might think they can barely speak at all.

Even for words that seem neutral, I have to be careful.

The word “household” gave me a lot of pause during the pandemic.

To many cultures in Canada, it’s normal for a household to include live-in grandparents, even aunts and uncles. There’s no need to say that this is a “large household” or a “multigenerational household” — it is simply a household.

But the reference point for the wider Canadian readership is most often the nuclear household. So journalists describing households that include “extended relatives” tend to include descriptors like “large” or “multigenerational.”

Which frames immigrant families who live in these arrangements as somehow odd compared to “normal” families.

When I wrote about how to protect large, multigenerational households during a pandemic, I found it tricky not to make it sound as though these families are crowding together when they shouldn’t — so I introduced lots of context about how widespread this is, and why.

But introductions can be cumbersome. Don’t get me started on the challenge of introducing terms from other languages into English.

If I mention a backyard barbecue in a story, I don’t need to stop the narrative and explain to the reader what it is: an informal gathering of family and friends coming together to cook food over some sort of open fire.

But if I mention something like mukbang that English readers might not be familiar with, I do have to stop and explain. Write too little, and the reader might not get it. Write too much, and the description eats away at the word count, interrupts the story and over-exoticizes an everyday phenomenon.

Imagine being a racialized journalist in a white-majority newsroom publishing a story about something from your culture. You might not actually know much about it, but your colleagues are looking to you for a definitive explanation. But even if they are hands off, it’s a lot of internal pressure — the representation of an entire civilization, resting on your shoulders!!

You may have noticed that italics are sometimes used for words unfamiliar to English readers.

Words lose their italics as they become “assimilated” into English, according to the federal Canadian Style. For example, “kimono” and “dim sum” now go unitalicized.

The unfamiliar ones are still italicized, and if I use too many of them — Khalsa and kirpan, bossam and budae jjigae, turon and turo turo — the style convention makes my story start to look like Tolkien’s Elvish or a Latin taxonomy.

But that begs the question of how to do a proper introduction if the reader needs it.

The need to find the right words affects policy-makers, too. After all, how can governments tackle problems they don’t even have names or definitions for?

A personal example: My great-grandmother, who lived in an East Vancouver care home until age 101, was served a western diet that was totally foreign to her, and she often skipped meals. She was also unable to communicate with the English-speaking staff in her native Cantonese. Her condition spiralled downward because of this, and it was painful to watch.

Nowadays, the concept of “cultural competency” is gaining more recognition in health care. The term acknowledges experiences like my great-grandmother’s.

“Once you design a definition, you can assign policy resources to it,” said Kevin Huang, the executive director of Vancouver’s Hua Foundation. The non-profit consults with governments on social issues such as sustainability and urban planning so that they’re more reflective of the cultures in the city.

A few years ago, Huang ran into a challenge when sounding the alarm over immigrant businesses like groceries being displaced by gentrification.

Should special places like this be defined reductively as “businesses”?

That leaves out the fact that they provide culinary comforts for immigrants, who also share their native food with Canadian-born children. They’re affordable for seniors and blue-collar workers. They’re rare safe spaces where immigrants can be together and speak their language, without the scrutiny and racism experienced elsewhere.

There wasn’t a term to describe these places that play a crucial role in the lives of diasporas, despite them being all over the region.

But Huang’s team noticed that they fit the criteria of what the City of Vancouver had called “food assets,” offering affordability, bolstering mental well-being and serving local products.

Still, the cultural component was lacking from the definition. So the non-profit began calling them “cultural food assets,” with the term increasingly recognized.

But such definitions can also backfire.

When I write phrases like “culturally competent health care” and “cultural food assets,” I can already hear the white gaze complaining about immigrants wanting special treatment and life catered to them.

You know, comments like, “If you love your own culture so much, why don’t you just go back to where you came from?”

Our systems left racialized people out in the first place. But ask to be included, and the language looks like they’re being given something extra.

Do you see my agony now?

Write the wrong word, give the wrong idea. Leave out the right words, lose a chance to inform.

NPR’s Code Switch podcast calls the language of diversity a treadmill to keep up with and says the descriptions we use will be in flux “as long as our orientations to each other keep changing.”

Rather than come up with hard and fast rules, here are some questions I think about to keep up with the treadmill.

Does the language other?

Does it lead to false impressions?

Does it omit important information?

Notice I didn’t call this series ‘Ignoring the White Gaze.’

Journalists writing about race, ethnicity and culture in Canada today need an awareness of how the white gaze works.

Not because it deserves to be catered to, but because inaccurate, negative stereotypes of racialized people need to be challenged and corrected.

If I’m writing about racialized people, places and cultures in Canada, I often have to justify how they live their lives to the white gaze.

If I don’t, there will be readers who jump to stereotypes.

It’s not just white people who do this. Racialized people may stereotype other racialized people; racialized Canadian-borns may stereotype people from their own background who are new arrivals.

If I talk about multigenerational households, I have to justify why they’re normal and why they exist. If I talk about astronaut families, I have to justify why they aren’t parasitic people, but a direct result of Canadian immigration policies.

You never know what words or topics might trigger racist stereotypes. It might be religious clothing. It might be foreign homebuyers. It might be the mere mention of Islam or Indigenous issues — commenting on stories to do with Indigenous issues got so toxic that the CBC made the decision in 2015 to close online discussions.

I often wonder if media should take some responsibility for that toxicity. If there is an outsized percentage of stories on racialized people as deviants — remember essay two? — should we really be surprised if audiences are internalizing what they’re seeing?

Journalists can add context to help counter stereotypes. But even then, you never know what readers might pick at.

I once wrote a story about B.C.’s lack of language support during the pandemic for people who speak languages other than English. It featured a Vietnamese-speaking refugee dad who doesn’t know much English. I knew there’d be readers who’d call him lazy or un-Canadian, so I explained the barriers for migrants like him.

This man tried to learn English multiple times over the years, but it was difficult because he grew up in a fishing family, without much childhood education, and as an adult had to work to support his family. To this day he still tries, popping into his daughter’s room to ask about vocabulary.

In response, readers wrote in with comments like “Language classes are free. Everyone has time.”

It’s frustrating that a story about the need for pandemic translation for our diasporas led readers to scrutinize their lives. But racialized people who share their experiences with Canadian media are often held to such unfairly high standards.

What are journalists to do about ugly comments on their stories?

I know of colleagues who ignore comments entirely to spare themselves from the toxicity.

I also know that the majority of readers are probably not like this.

But I do think that some of that ugliness needs to be considered. The fact that people see a headline about something like “birth tourism” and scream “immigration cheats” gives us an important sense of the world we are writing in.

Rather than cater to every vocal reader, it’s a reminder that journalists have a diplomatic role to play as ambassadors and interpreters.

Yes, it can be frustrating to explain everything from culture to injustices that are everyday realities for racialized people. Yes, it’s especially burdensome for racialized journalists in these roles to see aspects of their lives missing or misunderstood.

But the white gaze is still with us, and there’s a lot of work to be done so that people in Canada can see each other for who they really are.

Discussion questions

Just one this time, but it’s a big one. Think of a time when the language used in journalism gave you an inaccurate or negative impression of a race, ethnicity or culture.

Readers’ corner

Thank you to a reader who introduced us to the “explanatory comma,” which racialized journalists like me use all the time and struggle with. Here’s a good explanation from a blog called White as Snow, Privileged as Queens: “An explanatory comma is the aside or comma after a word, idea or person is introduced in an effort to define it for an audience that needs the explanation.... [A podcast] paid tribute to Tupac Shakur without providing an explanation of who he was. They then received a number of comments from listeners complaining that they felt left out. In particular, a self-identified 54-year-old white woman stated that she could tell Tupac meant a lot to the hosts, but she never felt invited in to the discussion, because she had no idea who Tupac was.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: