[Editor’s note: This series republishes “Hell’s History: The USW’s fight to prevent workplace deaths and injuries from the 1992 Westray Mine disaster through 2016,” commissioned by the United Steelworkers union and downloadable for free as a PDF here.]

This series ending today has traced the fight by the United Steelworkers and their allies to hold employers criminally responsible for preventable worker deaths. Their efforts produced the Westray Act, passed after 26 coal miners died in an explosion that rocked Nova Scotia’s Westray mine in 1992. “Kill a worker, go to jail,” has been the rallying cry since, as unionists press regulators, police, prosecutors and lawmakers to use the Act to hold employers accountable.

Previous stories this week asked why Westray so far has not been used in the case of a worker killed by a boulder on a remote B.C. mountainside job site, nor in the cases of four workers who died in B.C.’s Babine and Lakeland mill explosions. Today, two more examples of justice denied to workers who were just following orders… to their deaths.

On Nov. 17, 2004, Lyle Hewer set to work following instructions given by his supervisor at Weyerhaeuser’s New Westminster sawmill. Hewer was told to clean out material from a hog, a high-speed grinder that reduces wood waste. The nearly 20-foot-high hopper that fed waste wood down onto the grinding mechanism of the hog often clogged, and workers were then ordered to enter the hopper and poke at the plug of wood and waste overhead.

Workers regularly climbed inside to manually remove waste-wood products and clear out any jams, even though the hog constitutes a “confined space” as defined in B.C.’s workers’ compensation laws. WorkSafeBC documents say that confined spaces represent “significant risk of injury and death.” The danger the material would be dislodged and bury the worker was well known at the plant, the investigator found. Well enough known that another worker, that same day, when ordered into the hog by a manager, had expressed fear of getting hurt.

Hewer climbed into the hopper, became trapped under its load, and was asphyxiated. Dead at age 51, he left behind a wife and two children.

Three years later, when WorkSafeBC vice-president Roberta Ellis announced a record-breaking fine of $297,000 against the company for its safety failures in the Hewer death, she said the punishment “arose out of a high-risk violation and the violations were committed willfully or with reckless disregard.”

At first, it seemed that Hewer’s needless death would lead to further consequences for the lumber giant. Investigators from both WorkSafeBC and the New Westminster police found that Weyerhaeuser management was aware the hopper was a safety hazard but had resisted repeated requests to fix it. After Lyle Hewer died, Weyerhaeuser repaired the hopper at a modest cost of about $30,000.

The New Westminster police recommended charges under the Westray amendments to the Criminal Code. But in spite of the glaring nature of the case and the urging of WorkSafeBC and police, the B.C. prosecution service declined to launch a prosecution. Asked in the Legislature, then-attorney general Wally Oppal indicated there was no need to explain the Crown’s reasons. His office (incorrectly) said the matter was under federal jurisdiction.

Union turns ‘private prosecutor’

The United Steelworkers union decided it wasn’t going to allow this needless death to go unpunished. So it sought leave from the courts to launch a private prosecution. Vancouver lawyer Glen Orris began a year of legal work to show there were reasonable grounds for a prosecution.

“Crown counsel rejected the recommendation of the New Westminster police that a charge of criminal negligence causing death was warranted against Weyerhaeuser,” said USW Western Canada director Stephen Hunt. “Therefore we have been left with no alternative other than pursuing a private prosecution to see that justice is done.”

Today, Glenn Orris recalls the case with frustration. “Although the Crown doesn’t have to give reasons for not laying charges,” he told me, “I assume that the decision reflected an opinion in the Crown counsel office that there was ‘no substantial likelihood of conviction’ on the base of the evidence. I believed that there was a charge to be laid and a case to be met. There was evidence, in my opinion, of gross negligence.”

Orris explained that private prosecutions are rare. Even as a long-serving veteran in the Canadian courts, he has attempted just four such prosecutions in his career. He advised the USW that if the prosecution relied upon the Westray Act language to charge Weyerhaeuser as a corporation with criminal negligence, “we could possibly get charges laid.”

The private prosecution was launched in March 2010 in New Westminster Provincial Court. Over three days of hearings in October and November 2010, Orris called 16 witnesses, presenting the Steelworkers’ case that there was sufficient evidence for Weyerhaeuser to be tried under the Westray amendments. In March 2011, provincial court judge Therese Alexander ordered a process hearing, allowing the prosecution to proceed. Orris indicated that he was prepared to proceed as prosecutor on behalf of USW.

However, the policy of the B.C. Crown is to take over and handle all privately initiated prosecutions itself. In August 2011, rather than proceed with the prosecution, having reclaimed the case, the Criminal Justice Branch stayed the proceedings against Weyerhaeuser, saying in a statement, “There is no evidence that management at Weyerhaeuser was aware that workers were entering the hog in these circumstances.”

“Once the judge made her ruling,” Orris said in 2016, “we had used all our options under criminal law. The standard of proof in criminal negligence is high — you have to show the company showed ‘wanton and reckless disregard’ for worker safety. In the Hewer case, I believed we had evidence that showed obvious disregard for safety. The company knew the hog was likely to clog and had discussed the safety issue in boardroom discussions, but Weyerhaeuser took its time. It was a low-priority issue.”

In 2016, looking back on the Hewer case, Orris remembers how shocked he was when he learned how many workers die at work every year in Canada.

“It still stuns me,” he said. “Why do we tolerate so many deaths at work?”

A deadly ‘run of muck’

The same question applies to the grim story of how two miners met their end five years ago in a Sudbury, Ontario nickel mine.

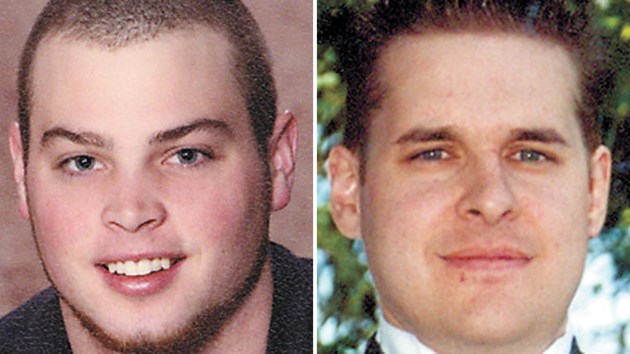

On June 8, 2011, Jason Chenier, 35, and Jordan Fram, 26, were working deep underground at the Vale Stobie mine near Sudbury when they were engulfed in a 350-ton “run of muck.”

Investigators found the flood of mud, rock and water that killed the two men was created by the company’s failure to deal with water issues in the mine. Before his death, Chenier warned his employer that Vale “should not be dumping or blasting this ore pass until the water situation is under control.”

Jordan Fram’s mother Wendy and his sister Briana support the demands of the United Steelworkers’ “Stop the Killing, Enforce the Law” campaign. Reflecting on Jordan’s death, Wendy Fram says in a moving video that “someone should be held accountable.” Briana says in the same video that she believes if the Westray Act were being properly enforced in Canada, mine management would have addressed the water safety issues that killed her brother before he and his co-worker died.

Vale was assessed a million-dollar fine for its safety failures in the two deaths, but none of the regulatory charges initially laid against management at the mine were pursued, and the Crown’s option to lay criminal charges under the Westray Act was not exercised, so the deaths of Jason Chenier and Jordan Fram have to be counted among enforcement failures during the law’s first decade.

Rick Bertrand is the president of USW Local 6500 and, when not working full-time for the union, is an employee at the Vale mine where Chenier and Fram died. He believes criminal charges should have been laid in the two deaths.

“This case was a perfect fit for Westray. Our investigation shows that management negligence killed Jason and Jordan,” a clearly exasperated Bertrand told me by phone in August. “The company refused to co-operate with us in investigating the deaths, so we had to do our own independent investigation. We made 165 recommendations for safety improvements at the Vale Stobie mine. I can’t tell you that the reforms have been adopted at every mine in Ontario, but I am happy with the work being done at Vale Stobie.”

Bertrand told me that the Westray Act is very important for worker safety in Canada and that it should be enforced more effectively. “If there is any neglect of worker safety and someone is killed or injured,” he said, “the responsible manager should go to jail.”

A new era of Westray enforcement?

Despite the setbacks and soft treatment detailed in this series, there are reasons for cautious optimism about how the law treats criminally negligent companies. In fact, the Westray Act looks to be in the midst of a belated increase in enforcement.

Brian Fitzpatrick is the father of Sam Fitzpatrick, the worker crushed by a boulder on the job at a hydro-project near B.C.’s Toba Inlet in 2009. He has never relented in his demand that the company and managers he holds responsible for the death of his son be brought to account. Last year, at last, the RCMP opened an investigation into whether Westray Act criminal charges should be laid against Kiewit construction company and some of the managers directly involved in Sam’s death.

This new investigation was opened as B.C. Mounties laid the first Westray-related criminal charges ever pursued in the province in another case. As noted in the first story of this series, criminal negligence charges laid March 15, 2015 against Stave Lake Quarries and two managers relate to the death of Kelsey Anne Kristian, a young and inadequately trained truck driver working in a Mission, B.C., quarry.

Last month, Stave Lake Quarries pleaded guilty to the charge and received a fine of $100,000 plus a $15,000 “victim surcharge” to be paid by April 2018. The charges against the managers were stayed.

In September 2015, in the first action based on the Westray Act in Nova Scotia history, charges were laid against auto body shop owner Elle Hayeck in the 2013 death of shop employee Peter Kempton.

Also noted in the first story of this series is the punishment meted in Toronto to Vadim Kazenelson, a construction project manager for Metron Construction. In January of this year, Kazenelson was sentenced to three and half years imprisonment in the 2009 Christmas Eve deaths of four men who fell from a swing stage suspended high above the pavement. The company was reportedly rushing completion of the work being done by these men in order to cash in on a $50,000 bonus for early completion, and Kazenelson was found responsible for overloading the swing stage with too many workers. It is notable, however, that charges against Metron’s president Joel Swartz were dropped and that the company was assessed a relatively modest $750,000 in fines for regulatory offences.

Also in Ontario, in April of this year, criminal negligence charges under the Westray Act were laid against Detour Gold’s Cochrane mine. The charges relate to the death in June 2015 of Denis Millette, poisoned by cyanide exposure while repairing equipment at the mine.

More signs of progress: In July, the B.C. Ministry of Energy and Mines signed a protocol with the province’s police agencies “for the investigation of mine site fatalities and bodily harm.”

USW director Steve Hunt emphasized that the protocol represented a message to employers.

“Our union’s first priority is to ensure the health and safety of all workers, but if tragedy strikes we also want to ensure that employers are held accountable. There are far too many examples of workers dying and employers getting off the hook. Through this protocol with police agencies, a clear message is being sent to mining companies that if they are negligent in a case of workplace death, they will be criminally investigated and held accountable,” he said.

It looks like a quarter century of work the United Steelworkers put into first passing the Westray Act and then campaigning to see it properly enforced is beginning to produce significant results. But if the sad path from Westray to Lakeland Mills has taught us anything, it is that hope is not enough. Whatever improvements have been made in the way the criminal law treats corporate killers have been won by organized workers putting pressure on politicians and regulators.

The next time you are subjected to the claim that unions were okay in the past but not needed now, please remember Robbie Doyle, Glenn Martin and 24 more lost Westray miners; remember B.C. mill fire victims Robert Luggi, Carl Charlie, Alan Little and Glenn Roche; remember, too, Sam Fitzpatrick and Kelsey Anne Kristian and Lyle Hewer and Jason Chenier and Jordan Fram and all the others. Remember the war on workers waged by companies that put profit over safety.

Find the full Hell’s History series by Tom Sandborn here. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: