[Editor’s note: This series republishes “Hell’s History: The USW’s fight to prevent workplace deaths and injuries from the 1992 Westray Mine disaster through 2016,” commissioned by the United Steelworkers union and downloadable for free as a PDF here.]

At 8:15 p.m., Jan. 20, 2012, the Babine Forest Products sawmill in Burns Lake, B.C. exploded. Robert Luggi, a lead hand and Carl Charlie, the #1 cutoff saw operator, were killed and 20 other workers were injured, many very seriously burned, as the fireball engulfed their workplace.

Only three months later, Lakeland Mills outside Prince George went up in flames fed, as at Babine, by an unsafe level of dry sawdust in the air and on surfaces throughout the mill. Glenn Roche and Alan Little were killed and 22 of their fellow workers were injured.

In a nightmarish mirroring of the 1992 Westray mine disaster recounted earlier this series, the lethal explosions at the mills took place in a context of work speedup and imperfect regulatory inspections, long, exhausting shifts and work sites covered with fine, flammable dust that should have been cleared away.

At Westray, the dust was from coal and at the B.C. mills it was dry, fine sawdust from trees killed by the province’s mountain pine beetle infestation. Underground at Westray, and in the B.C. mills two decades later, the explosive, combustible dust was allowed to accumulate.

And, in the case of Westray and the B.C. mills, regulatory inspections and worker complaints about safety defects were reported to have been effectively ignored. Before all three explosions, workers warned that disaster was looming.

WorkSafeBC is the provincial regulator responsible for mill safety. Its “long-awaited” findings, the CBC reported in January 2014, concluded “the disaster could have been prevented if mill management had been doing its job.”

Two decades after Westray and nearly a decade after the Westray Act was passed to hold employers criminally responsible for knowable dangers, some things on Canadian work sites hadn’t changed enough to prevent the loss of life in the flaming mills.

In January 2016, survivors of the dead workers filed a suit against WorkSafeBC, alleging negligence on the part of the regulator led to the fatal tragedy.

In another echo of the Westray story, Crown counsel declined to lay criminal charges against any of the management figures at the two mills for their part in the deaths and injuries, saying that WorkSafeBC had so badly bungled the initial investigation into the fires that there would be no reasonable possibility of getting a conviction. Twenty years later, the Canadian justice system still apparently couldn’t deliver when confronted by compelling evidence of lethal negligence on the part of management.

And in one more darkly ironic twist, Lakeland management went on in July 2014 to treat the bungled WorkSafeBC investigation and Crown counsel decision not to lay charges as the rationale for an appeal against the $724,000 fine WorkSafeBC had levied against the mill. A month earlier, Babine management had similarly appealed the $1-million fine WorkSafeBC had levied against the company, citing alleged procedural flaws in the regulator’s investigation and Crown counsel’s decision not to lay charges.

The press release in which Lakeland Mills management announced their intention to challenge WorkSafeBC’s fine suggested that the Crown counsel decision not to lay charges totally exonerated the firm. It read in part:

“Crown counsel reviewed all the same evidence as WorkSafeBC. The Crown published a clear statement that concluded that a sawdust-related explosion was a ‘previously unrecognized hazard’ to both the B.C. sawmilling industry and WorkSafeBC. The Crown even discovered that a WorkSafeBC officer responsible for inspecting the Lakeland mill in the months prior to the incident did not observe a dust violation and in fact believed Lakeland was a ‘clean mill’ compared to others.”

The Crown said, according to the Lakeland release, that the “risk of catastrophic explosion was not foreseeable to Lakeland.”

But does the evidence support this claim? Were the murderous fireballs that raged through the two B.C. mills really such a surprise? Not according to an application to certify a class action suit against WorkSafeBC and the province of B.C. filed Jan. 11, 2016.

The application, which named 10 potential plaintiffs with connections to the two mill fires (as workers injured in the fires, workers who were off shift when the fire occurred and family members of on- and off-shift workers), suggests that any silence from WorkSafeBC on dust and safety issues at the mills reflects not the absence of danger but a failure on the part of WorkSafeBC inspectors to do their due diligence and recognize the mills for what they were, ticking time bombs waiting to go off.

According to a Globe and Mail story published Jan. 12, 2016, the application referenced at least 24 separate inspections of the Prince George mill in the years leading up to the April 2012 explosion, uncovering unacceptable levels of wood dust, yet producing no WorkSafeBC orders to clean up.

Further, the claim alleges that “WorkSafeBC’s conduct was reckless and departed to a very marked degree from the standard of conduct expected of a responsible and competent inspector.”

And evidence from the U.S. introduced at the coroner’s inquest into the Lakeland mill fire reports on many American incidents involving fine dust, explosions and fires. Shouldn’t someone in authority in B.C. have been paying attention?

The coroner’s inquest viewed a U.S. Chemical Safety Board video from 2007 that outlined the dangers of dust explosions involving substances as diverse as rubber and aluminum. Research by the board indicated that between 1980 and 2005 in the U.S., fine dust caused 281 explosions and fires in plants, killing 119 people and injuring 718. Since 2005, another 71 dust explosions have occurred.

So, were the deaths at the Babine and Lakeland mills unforeseeable and unavoidable, the kind of shocking surprise no one could have anticipated, as WorkSafeBC ruled?

Or were numerous warning signs ignored in a rush for corporate profit that was facilitated by incompetent or irresponsible inspection and enforcement by WorkSafeBC?

A history of cautionary events

The catastrophic mill fires in 2012 were far from being the first time that sawdust and wood chips were implicated in explosions and fires. According to an April 2, 2014 Globe and Mail article, WorkSafeBC held a workshop in March 2010 that was attended by its own prevention officers, on the dangers of combustible dust. There the officers were told “a layer of dust as thin as a dime” was dangerous, but they “failed to bring this information into the mills.”

In July 2012, Gordon Hoekstra, writing in the Vancouver Sun, reported on a decade’s worth of reports from the B.C. Fire Commissioner, reports spanning 2001 to 2011. More than half of the 89 mill fires reported during that decade featured sawdust or chips as the first material to burn (and three arguably dust-involved fires occurred at the Lakeland mill itself, in 2004, 2006 and in 2012 when a fire broke out in the dust-filtering ‘baghouse’ section of the mill.)

According to the Sun story, the fire incident reports also found:

In May 2005, at Tolko’s Soda Creek sawmill in Williams Lake, wiring to an electrical motor had loosened and arced, igniting dust and sawdust in the room and creating a “minor” dust explosion.

In July 2009, at West Fraser sawmill in Williams Lake, large fuses blew, igniting dust above panels. Fire damage was minimal.

In October 2006, at Canfor’s Prince George sawmill, an electric short of breakers caused sparks that ignited fine sawdust in the lumber edger. Damage was contained to electrical controls and catwalk.

In August 2011, at Dollar Saver Lumber in Prince George, sparks from an overheated electrical motor ignited sawdust and hydraulic fluid. The interior walls of the compressor room were charred.

Babine: A speed-up until disaster

In November 2011, a WorkSafeBC inspection cited dust in the Babine mill “in excess of the acceptable exposure level for employees’ health and safety.”

Steve Dominic, a Babine worker, told the coroner’s inquest that when WorkSafeBC came to test the dust levels in the mill, the apparatus that was supposed to measure particles in the air for his entire shift became plugged after only two hours.

But the inquest jury looking into the Babine Forest Products fire didn’t just hear about failures of prevention before the disaster. It also heard harrowing stories from workers who were at the mill when it exploded.

According to a July 16, 2015 report on First Nations Radio, Ryan Clay described how he had just hit send while texting his future wife about how much he was looking forward to going on a two-week vacation next week, just as the mill exploded.

He said that if it weren’t for a wall blowing out, he wouldn’t have been able to escape his office, as all the exits were blocked by burning debris. Calmly, he described reaching for his radio to call for help, only to see the skin on his hand melt off.

Clay told the inquest how the week leading up to the explosion was full of mishaps as the extremely cold weather froze water pipes, broke equipment and forced the mill to close windows in an attempt to keep workers warm. He also spoke of very little communication between workers, the company management, the union and WorkSafeBC.

Next to the stand was Steve Dominic, who was working in the basement when the explosion occurred. Dominic was overcome with emotion when he was asked when he last saw Robert Luggi. He said that Luggi went to check on a malfunctioning machine that Dominic normally would’ve gone to work on, but because he was already busy, Luggi went in his place right before the mill exploded.

Dominic told jurors how he thought he was going to die after being thrown against a concrete wall and to find himself on fire, and when he looked up, instead of the ceiling, he saw the sky. He said he jumped into a puddle of water and rolled around, only to be set on fire again by secondary explosions.

Just when he had mentally said his last goodbyes to his family, he was able to join two other workers and escape the burning mill.

Claude Briere, a longtime machinist and millwright at the mill, told the inquest that conditions “totally changed” after shifts were extended to 10 hours from eight hours in an effort to boost production. Before that, Briere said there was no dust on the beams, the floors were clean and the debris was removed when he arrived at the mill every morning.

“After the 10-hour shift, the piles were there from the day before, or the day before or the day before or the day before,” he said, adding a crew had less time for cleanup duties because they were also required to do other duties.

The shift change was introduced after Oregon-based Hampton Affiliates bought the 30-year-old mill from West Fraser in 2006, he said. It seems fair to suppose that the extended shifts and reduced time for cleanups could have increased the volume of dust in the mill, thus making the explosion that occurred on Jan. 20 more likely.

A USW report on the deaths at the Babine mill notes that the operation had experienced a fire in February 2011, a fire blamed on excessive dust in and on mill machinery. The fire did half-a-million dollars in damage.

In December of the same year, a WorkSafeBC inspector remarked on excessive dust levels. On Jan. 20, 2012, Robert Luggi spotted and extinguished another fire early in his night shift.

Around 8 p.m., the fire that killed Luggi and Roche and seriously injured most of the men on shift that night broke out. Men who survived the flames told investigators of seeing a pillar of flame from the mill’s #3 line and hearing explosions.

Lakeland workers warned of another Babine

Ronda Roche, the wife of Glenn Roche, one of the two men who died in the Lakeland Mills explosion, told the coroner’s inquest into his death that her husband often expressed concerns about the mill’s safety.

“After the explosion at Babine in January 2012, he was extremely concerned that Lakeland could end in the same fate,” she told the coroner.

“The day before Babine, he assisted in putting out a fire in his work area. He described it as a huge fireball and stated that it wasn’t just a regular fire but that the air in front of him was on fire. I told him he should have just got out, but he insisted that they had to put it out so they’d have a job to go to. The next day Babine exploded. I remember just how devastated he was. He was — he was — it was like he knew everybody there. He kept saying, ‘My brothers have suffered.’”

Brian Primrose, a Lakeland worker who survived the flames that killed Alan Little and Glenn Roche, told the coroner’s inquest he had protested to mill management about dust conditions after the Babine explosion. He testified that he demanded of managers: “What the hell have we got to do? Are we just going to wait until somebody dies before we do something about this?”

A United Steelworkers staff member has prepared a damning timeline of the events leading up to the Lakeland Mills fire that begins in 2008 with a Prince George fire department instruction that safety planning is lax at the mill, and ends, four years later and just over a month before the deadly explosion, with yet another fire department warning (see sidebar: “Lakeland: A Timeline of Danger Foretold”).

On March 22, 2015, the USW withdrew its participation in the coroner’s inquest into the deaths at Lakeland. Stephen Hunt, the union’s District 3 Director explained why:

“Over the past week, the inquest has heard how WorkSafeBC’s failure to carry out its mandate to ensure the health and safety of workers resulted in a complete mishandling of sawmill safety both before and after the explosion. Despite this tragic failure to do its job, the agency is not being held accountable.

“As a result of relying upon WorkSafeBC’s flawed investigation, the RCMP and B.C. Safety Authority also produced failed investigations. It is now clear that the inquest is not going to adequately answer any of the questions that demand to be answered. The withholding of crucial evidence from the employer would have made a difference as to how the USW conducted its case and we will not participate in an exercise that does such a disservice to the families who lost loved ones and to the larger community.”

On October 9 of last year, the USW repeated its previous calls for an independent inquiry into the twin sawmill disasters. The union had obtained a WorkSafeBC memo written after the Babine explosion but before the tragic repeat at Lakeland. The memo, by the regulator’s safety enforcer for the region, fretted about industry “pushback” if safety standards were stepped up (see sidebar: “Memo with Deadly Consequences?”)

Things did not improve after USW’s withdrawal. Neither the Lakeland nor the Babine inquests, nor the WorkSafeBC investigation reports led to any criminal charges being laid by Crown counsel in the explosions, and the modest regulatory fines imposed on mill management at Babine and Lakeland by WorkSafeBC were almost immediately appealed. Crown counsel blamed what they saw as procedurally flawed WorkSafeBC investigations at both mills for diminishing the chances of getting any convictions and declined to lay charges.

The premier tasked her deputy minister, John Dyble, with generating a report on improving co-operation between WorkSafeBC, the RCMP and Crown counsel in future industrial deaths. She also appointed Gord Macatee as a temporary administrator at WorkSafeBC, tasked with producing internal reforms and new policies to improve accident investigation and cooperation with the justice system. So, a lot of ink was spilled and voluminous reports were created, but it remains to be seen whether any of these bureaucratic exercises will succeed in protecting workers’ lives.

Calls persist for an independent inquiry

In the meantime, the independent inquiry into the mill fires has not been called and B.C. Premier Christy Clark has indicated she does not favour such an inquiry.

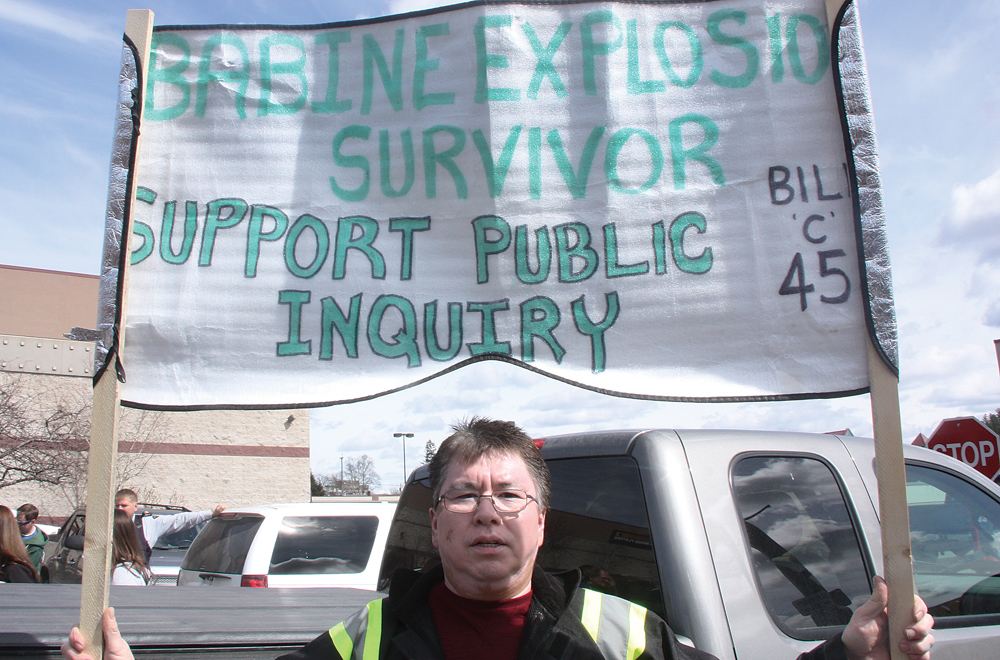

Many in labour and the First Nations communities disagree with the premier. For some time now, the USW has joined with the BC Federation of Labour, the First Nations Summit and the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs in calling for an independent inquiry. On Jan. 20, 2016, these groups issued a statement on the anniversary of the Babine mill deaths, saying, in part:

“(We) are renewing our collective demand for Premier Christy Clark to honour her commitment to answers and accountability, and immediately establish an independent public inquiry to ensure tragedies like these never happen again.

“Coroner’s inquests were held in 2015 into the explosion at the Babine sawmill, as well as the explosion that occurred three months later at the Lakeland Mills sawmill in Prince George on April 23, 2012, killing Alan Little and Glenn Roche, and seriously injuring another 21 workers. These inquests, as a strictly fact-finding process, left the families and the victims with more questions than answers.

“No justice or substantive changes resulted from these inquests. It is important to note that the lay jury’s recommendations, although comprehensive and well-intentioned, are only voluntary and do not have the power to ensure the necessary changes are made in order to hold the employers, the government and other organizations such as the Workers’ Compensation Board accountable.

“The Coroner’s inquests were also limited to the events leading up to the incident, and not the seriously flawed investigations that followed. Questions remain unanswered, including why did the policies and practices that are supposed to protect workers fail to do so?

“The surviving families, the victims and all workers in British Columbia deserve justice. It is time for real and meaningful changes that will protect working people and ensure that these tragedies never happen again.”

Tomorrow the series wraps: Two more cases of killed workers denied justice, and the ongoing fight to make the Westray Act stick. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: