Tim Slaney doesn’t know how much longer he can keep working in harm reduction, or if he can ever walk away.

In Lethbridge, Alberta, where Slaney lives, an illicit drug supply overrun by fentanyl and other highly-potent substances killed 53 people in the first 10 months of 2021 alone, according to the latest available data. With two months remaining in the year the death toll already matched the record number from 2020. That year, the windswept Prairie town had the highest opioid-related death rate among all major cities in the province. It’s only crept up since then.

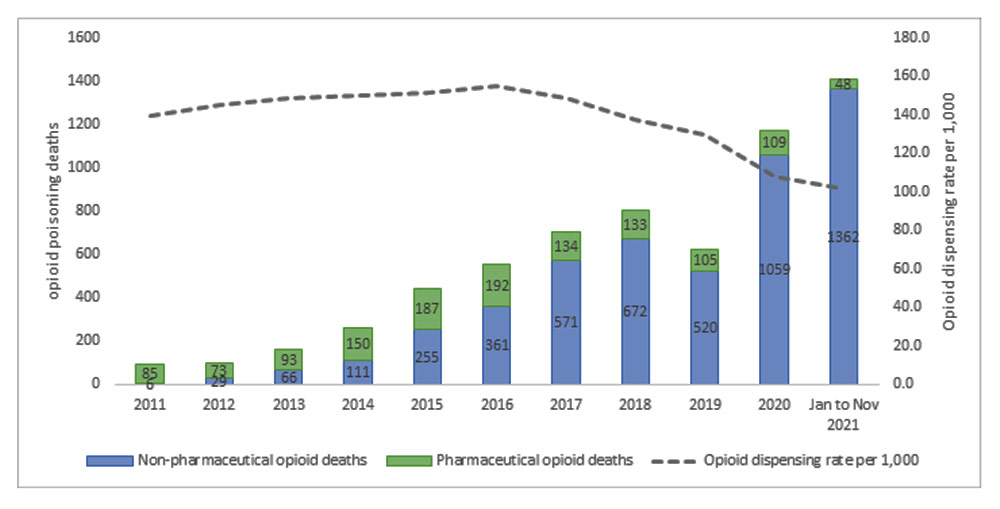

The situation is grim across the province. More Albertans have died from drug poisoning in 2021 than in any previous year — more than twice the number of drug-related deaths than in 2016, the same year neighbouring British Columbia declared its dramatic rise in overdose deaths a public health emergency. Indigenous communities have been hit the hardest. Opioid overdoses, which make up the vast majority of toxic drug deaths, killed Indigenous people in Alberta at seven times the rate of non-Indigenous people in 2020.

Drive 45 minutes southwest of Lethbridge to Blood 148, a reserve home to the Kainai First Nation, and the weight of loss will overwhelm you. Between April 2020 and March 2021, the nation lost 91 people to toxic drug poisoning, equal to roughly one per cent of its reserve population.

Across the country, and throughout history, systemic barriers often rooted in stigma towards people who use drugs have made it harder for harm reduction workers and advocates to do what they see as vital, lifesaving work. Today in Alberta, the fight for harm reduction feels especially relentless.

Slaney has tried to do what he can to save lives, but roadblocks seem to come up at every turn.

He previously worked at Arches, Canada’s busiest supervised consumption site, before the province pulled its funding due to alleged financial mismanagement in the summer of 2020.

After it closed, Slaney and other former Arches employees helped set up Alberta’s first unsanctioned overdose prevention site in a downtown park.

But the initiative was quickly disrupted by angry protesters, a stack of municipal fines and a constant police presence that prevented people from using drugs under the volunteers’ supervision. Slaney’s group, the Lethbridge Overdose Prevention Society, hoped to eventually set up a legal supervised consumption site at a brick-and-mortar location, but he says new regulations the province imposed on these facilities last June killed that plan.

The staggering loss of life, meanwhile, has taken a toll. Last year was the worst of his life, Slaney told me.

“This is a job that really demands connection. You have to get to know people. You have to really understand how someone works,” he said. “And you start to care about people pretty deeply at that point. And to have that many losses.... At first, it crushes you, and then it makes you numb.”

Many of his old co-workers no longer work in harm reduction, and Slaney doesn’t fault them for it. But he feels like he has no choice.

“At the end of the day, I’m a person who uses drugs,” he said. “I get up, I go fill my Suboxone. I can’t turn a blind eye to it because I have to stand in line with these folks. I am these folks.”

What makes it even harder, he says, is that sometimes it almost feels like there is no crisis at all because, “you can’t get anyone to acknowledge that it’s happening.”

Politicians can’t agree what the problem is

A couple of weeks before I talked to Slaney, Alberta’s legislative committee examining the efficacy of safe supply met for the first time. Safe supply means providing untainted, pharmaceutical-grade substances to those who use drugs.

Lori Sigurdson, an MLA from Edmonton and the NDP’s critic on addictions and mental health, proposed they begin each meeting with a moment of reflection for people who have died due to drug poisoning.

Jason Stephan disagreed slightly, according to CBC News. The United Conservative Party MLA from Red Deer suggested they instead recognize “lives lost due to drug addiction.” He said that was the “root cause” behind the province’s mounting drug-related deaths.

Another NDP MLA pointed out that people without a substance use disorder have also died due to an illegal drug market that, countrywide, is becoming increasingly lethal. Think of the teenager who buys fentanyl-laced MDMA for the first time before a rave, or the business executive who uses tainted cocaine on a whim during a late night out.

“I think acknowledging the role of drug poisoning in the context of a toxic supply is an important consideration when the purpose of this committee is to discuss the option of safe supply,” said David Shepherd, an NDP MLA representing the riding of Edmonton-City Centre.

The committee compromised, and a motion was passed to recognize both groups.

Addiction or poisoning: it might seem like quibbling to some, but this difference magnifies a fundamental political issue hindering Alberta’s response to this crisis.

After nearly three years in office — two of which saw by far the highest number of drug-related deaths in the province’s history — Premier Jason Kenney’s government seems unwilling to confront the main reason why drugs are killing Albertans at record rates.

“There just doesn’t appear to be any concerted action on the part of the government to address drug poisoning or try to prevent people from dying,” said Dr. Elaine Hyshka, an associate professor and Canada Research Chair in health systems innovation at the University of Alberta.

About two weeks after Alberta’s safe supply committee began its work, all four NDP members abruptly resigned from the committee, calling it a “political stunt.”

The exodus came after the UCP announced the controversial list of speakers it had invited to share their thoughts on safe supply. Several of the invitees have vocally come out against safe supply, including a Simon Fraser University professor who has called it a “vacuous practice.” Another invited guest is the author of the book San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities.

A few days later, two pro-harm reduction groups the NDP had invited to present said they wouldn’t take part either, pointing to the “American-style prohibitionist views” of several folks on the UCP’s list. However, several vocal safe supply advocates — like former B.C. provincial health officer Perry Kendall and Cheyenne Johnson, executive director of the BC Centre on Substance Use — were later invited by the now UCP-only committee.

From the get-go, the NDP worried the committee had only been formed to discredit safe supply, much like how the government's notorious review two years earlier seemed intent on smearing supervised consumption sites. That review panel was asked to only study how these facilities impact neighbourhoods, not whether they save lives.

Plus, the premier himself has made a habit of publicly disparaging safe supply. It’s a model supported by public health officials like Dr. Bonnie Henry and which Kenney says only serves to “facilitate addiction.” A year ago, Alberta said it wouldn’t even consider safe supply, now available in limited form in four other provinces and, as of August 2020, supported by nearly 60 per cent of Albertans.

“What the NDP now wants to do is adopt so-called safe supply policies, where the government delivers dangerous drugs to people who are coping with addictions,” Kenney told the UCP’s annual general meeting a couple of weeks before the committee was formed.

“Instead, we are presenting the option of hope, of lifetime recovery from the trap of addictions. That is compassionate conservatism.”

The committee, now composed of eight UCP MLAs, must submit a report with its recommendations to the legislative assembly by the end of April.

A narrow approach

“Recovery is possible.”

Those three words have become something of a mantra for Kenney’s government, which hasn’t wavered from its original “recovery-oriented” approach despite the worsening crisis.

In early December, Kenney joined fellow UCP MLA Mike Ellis, Alberta’s associate minister of mental health and addictions, to announce that the province is now funding more than 8,000 treatment beds annually, double the amount it had promised two years earlier.

“Right now, we are completely focused on recovery,” said Ellis, a former police officer from Calgary who took over the file last summer. That same week, emergency responders across the province faced a record number of opioid-related calls, over a hundred more than in any week in 2020, according to the provincial data.

The Tyee made multiple requests for an interview with associate minister Ellis but did not receive a response.

The premier has strived to make traditional addiction treatment, particularly abstinence-only programs, more accessible. He’s eliminated fees at publicly funded recovery centres and invested $25 million to build five “recovery communities.”

Soon, a slick new app called My Recovery Plan will help people tailor their own treatment and track their progress. Folks in Edmonton can head to their local firehall for referral to treatment, while people across the province can now seek help through the police officer who just arrested them.

Both initiatives have received intense criticism from public health experts who say other places, like supervised consumption sites, are better equipped to help and are more trusted by people who use drugs.

Besides looking at things like drug-related deaths and non-fatal overdoses — which both continue to go up — it’s hard to say exactly how successful the Kenney government’s emphasis on recovery has been. The provincial government doesn’t release, nor is it clear if it collects, any data about how many people are accessing treatment, how many are completing it, and so on.

But to harm reduction advocates, the government’s strategy doesn’t match the reality on the ground.

“The only response they have to overdoses is treatment, and people don't live long enough to make it there,” said Petra Schulz, a co-founder of Moms Stop the Harm, a national organization of bereaved parents that pushes for progressive drug policy.

Moms Stop the Harm was one of the organizations that decided not to take part in the legislature’s safe supply committee.

Not everyone who uses drugs wants to seek recovery or necessarily needs to, Schulz added. Nor is sobriety attainable for everyone.

A ‘third way’ of using drugs

Ophelia Cara has tried to live sober, but it just hasn’t worked.

The Calgary resident, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, has also tried taking Suboxone and methadone, opioid agonist therapies that can ward off cravings and prevent withdrawal. But they didn’t work for her either.

“In an ideal world, everyone should be getting sober,” Cara told me. “In an ideal world, no one should be using drugs. In an ideal world. But that's not the world that we live in.”

Cara now takes a doctor-prescribed IV dosage of hydromorphone, an opioid similar to morphine or heroin, every day. This has given her stability. She hasn’t overdosed in more than a year, and no longer drinks nor uses other drugs.

Cara works and goes to school with the aim of one day earning a PhD in narcotic chemistry and psychoactive pharmacology. She says her relationship with her family has improved, and so has her mental health, something the young woman has severely struggled with ever since she was a child.

“I didn't know that there was a third way [of using drugs],” she said. “I thought that it was either sobriety or destructive, out-of-control drug use.”

Cara believes a prescription like hers should not be the first resort for people struggling with drug use. She thinks they should first attempt sobriety or other forms of treatment, as she did.

She says it would be catastrophic if she lost her prescription.

“I don't know what I would do — somewhere between throwing myself off a bridge and relapsing on heroin, like hard,” she said. “But with this prescription, I am able to live a normal life. And on top of that, I am genuinely happy. I didn't know that it was possible to actually be this happy and this stable. But apparently it is.”

‘Crafted to kill harm reduction’

Dr. Elaine Hyshka believes it’s a good thing the province has made recovery services more available. Every other harm reduction advocate I’ve spoken to agrees.

But expanding access to recovery programs or mental health support without confronting the toxic supply of criminalized drugs is simply “not enough” to stem the bleeding, Hyshka says.

“It feels like there’s been a lot of policy changes that are actually limiting access to what we know are effective interventions to help people,” she told me.

For instance, the provincial government announced in 2020 that it would end a lauded treatment program for people in Calgary and Edmonton with severe opioid dependencies called injectable opioid agonist therapy.

One patient interviewed by The Tyee credited iOAT with saving his life. But others abandoned the treatment after the government announced it would soon close. In the end, Alberta reversed its decision and again funded the program after a group of iOAT patients sued the province and the federal health minister urged the government not to end it. However, today no new people can join the program.

And then there’s the uncertainty that has loomed over supervised consumption sites — which Premier Kenney has called “NDP drug sites” — since the day the UCP came to power.

After the facilities opened during the NDP’s time in office, Kenney railed against them as the leader of the Opposition. As premier, he still criticizes these facilities, while his government embraces a confusing, zigzag approach that leaves many critics scratching their heads.

Try to follow along: First, the province froze funding for three planned facilities. Then it closed sites in Lethbridge and Edmonton, and another will soon shutter in Calgary. Yet now Alberta plans to open two overdose preventions sites — which are temporary and offer less resources than supervised consumption sites — to replace the soon-to-be-closed Calgary facility, as well as another OPS in Edmonton, where, again, it closed a supervised consumption site last year.

To the folks who operate, work at and advocate for harm reduction facilities, it can feel like the point is to keep them on their toes.

“I can’t celebrate getting back what they should have never taken away,” said Petra Schulz of Moms Stop the Harm, after Alberta announced it would open more overdose prevention sites in Calgary and Edmonton.

And while the provincial government seems comfortable introducing some limited forms of harm reduction, Hyshka says the province may ultimately not grasp the significance of the changing drug supply — what she calls the “roots of the crisis.”

If the government did, she says, it would inevitably embrace more evidence-based measures like supervised consumption sites, iOAT and safe supply.

Schulz holds a less generous view: “Kenney understands the evidence, and he chooses to ignore it.”

She continued, “What the data is telling [the UCP] doesn't fit into their ideological worldview. They’re still fighting harm reduction. They’re still not talking to anybody who doesn’t agree with them. Nothing has changed.”

Last summer, Alberta became the first province in Canada to introduce its own set of regulations for supervised consumption sites, which already must follow federal standards. The province says the new rules will assure quality and safety at these facilities, and help people access other forms of health care. Harm reduction advocates, meanwhile, say the regulations make it harder for grassroots groups to open supervised consumption sites — and may discourage people who use drugs from visiting these sites altogether.

The new rules require an extensive degree of reporting, data collection and community engagement that critics say small, volunteer organizations like the Lethbridge Overdose Prevention Society can’t meet.

“They are really cleverly crafted to kill harm reduction before it ever takes off in any other cities,” Slaney said. “If they have the authority to come and shut you down, it doesn’t matter what you do on the grassroots level.”

In an unprecedented move, supervised consumption sites must now also ask for a person’s identification, in the form of a personal health number, when they first visit the facility. The province says people won’t be turned away if they refuse.

Still, Schulz says this new policy runs counter to the very ethos of supervised consumption sites as low-barrier services intended to meet people where they are. A 2016 study out of the University of Alberta found that only 36 per cent of people who use drugs said they’d still go to a supervised consumption site if they had to show identification. Not only are people reluctant to identify themselves because they’re engaging in illegal activity, but they’re also afraid of the stigma they may face if their visits to a supervised consumption site appear on their permanent health record.

Last summer, Moms Stop the Harm and the Lethbridge Overdose Prevention Society filed a lawsuit claiming the new rules violate several fundamental charter rights, including the right to life. Out of fear the new standards could contribute to more toxic drug deaths, they’ve asked the Supreme Court of Canada to dramatically expedite the trial. Otherwise, it likely won’t begin for at least two years.

In the meantime, the federal government could intervene if it so pleased. In January, Moms Stop the Harm sent a letter to Carolyn Bennett, the federal minister of mental health and addictions, asking the Trudeau government to formally assert its jurisdiction over supervised consumption sites and “clarify” that collecting personally identifying information is not allowed. But Bennett wouldn’t commit to it when she met with Schulz in January.

“I'm not optimistic we will get help from the federal government,” Schulz said. “And that is especially disheartening — knowing that they could step in here and fix the problem instead of sending a couple of small non-profits to take governments to various levels of courts."

The community steps up

Avnish Nanda doesn’t think he can change the government’s mind.

“They don’t care about the lives of substance users in this province,” he told me. “There’s no argument I can make to persuade the people in power to change.”

But the young Edmonton-based lawyer representing Moms Stop the Harm and the Lethbridge Overdose Prevention Society in their fight against the province’s new regulations thinks he can persuade the courts, including the court of public opinion.

I had last spoken to Nanda in the fall of 2020, when he was representing iOAT patients in their lawsuit against the province. At the time, I encountered nurses, academics and frontline workers devastated by the Kenney government’s handling of the crisis, but reluctant to speak up out of fear of retribution. That still exists. But Nanda believes a culture shift around harm is taking place across Alberta.

“Civil society has just blown up,” he said. “I’m way more optimistic. It’s night and day.”

In recent months, medical associations have become more critical of the government’s handling of the crisis. And more grassroots groups are forming. One of them is Each+Every, a Calgary-based collective of businesses aiming to destigmatize drug use and promote harm reduction across Canada. Like other proponents of harm reduction approaches to the drug policy crisis, Each+Every also dropped out of presenting to the provincial safe supply committee.

“At the end of the day, the solutions are going to have to come from the community because they're not coming from the government,” said Each+Every co-founder Euan Thomson. He says the collective now includes more than 175 businesses, most of which are based in Alberta.

Still, Thomson believes a lot more activism is needed to push back against the province’s “hurtful” approach to rising toxic drug deaths.

Schulz agrees, but she doesn’t necessarily consider what she does activism. She says the Kenney government has turned the word “activist” into a slur, pointing to the “combative” rhetoric the premier and associate minister Ellis regularly employ on social media.

“What I really am is a bereaved mom,” she told me. “I’m doing this work because I lost a child, and I don’t want other people to lose their children.”

In 2014, her son, Danny, died from an accidental fentanyl overdose in Edmonton. He was 25. Like Slaney, Schulz doesn’t really have a choice. She can't walk away from this work either.

“There isn't a day where I don’t think about Danny, and how the outcome for him could have been so different,” Schulz told me.

“First, you think your kid dies because he takes drugs, but then you realize that your kid died because the drug policies are just really screwed, and they need to be changed.... When you realize that, you can't stop and give it up.”

It feels like every time I read an article about the toxic drug crisis in Alberta, I see Schulz’s name. But, she admits, she can’t sustain this level of advocacy forever.

“There are days where I don't get shopping or laundry done because I'm just in front of my computer,” she said.

“It's the intensity, but also the setbacks. Not just the setbacks from the government. The personal ones — the people that you try to keep alive, dying. That is the hardest part.”

But new allies are constantly joining the movement, she says. And that gives her hope. That gives her strength. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: