It’s a rainy October morning in Vancouver’s Gastown neighbourhood. It’s early and the streets are empty, except for a small group of unhoused people huddled under the awning of a closed shop, their belongings stacked around them.

Gastown, filled with upscale restaurants and fashion boutiques, lies beside the city’s poorest neighbourhood, the Downtown Eastside. Scenes like this prompt complaints that the Downtown Eastside is “spilling over” into Gastown, and questions about whether the neighbourhood will ever "get better."

Just a few floors above the group under the awning, Eris Nyx, a 30-year-old musician and harm reduction worker at the SRO Collaborative, is trying to order heroin on the dark web while her cat, Mewsolini, prowls around her tiny studio apartment.

It’s not easy. “One guy retired from his market, so he shut it down — it was one of the biggest and best ones on the dark web,” Nyx says. Another large, reliable market called Canada HQ also recently shut down after being targeted by multiple denial of service attacks.

Today Nyx has her eye on two other markets. Buying drugs this way is tedious — like ordering from a buggy, slow version of Amazon that keeps crashing — but Nyx says it’s the only place to find drugs that are what the seller says they are.

Nyx and Jeremy Kalicum, a 26-year-old drug-checking technician at Substance, a drug-checking project on Vancouver Island, have been buying heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines this way since 2020.

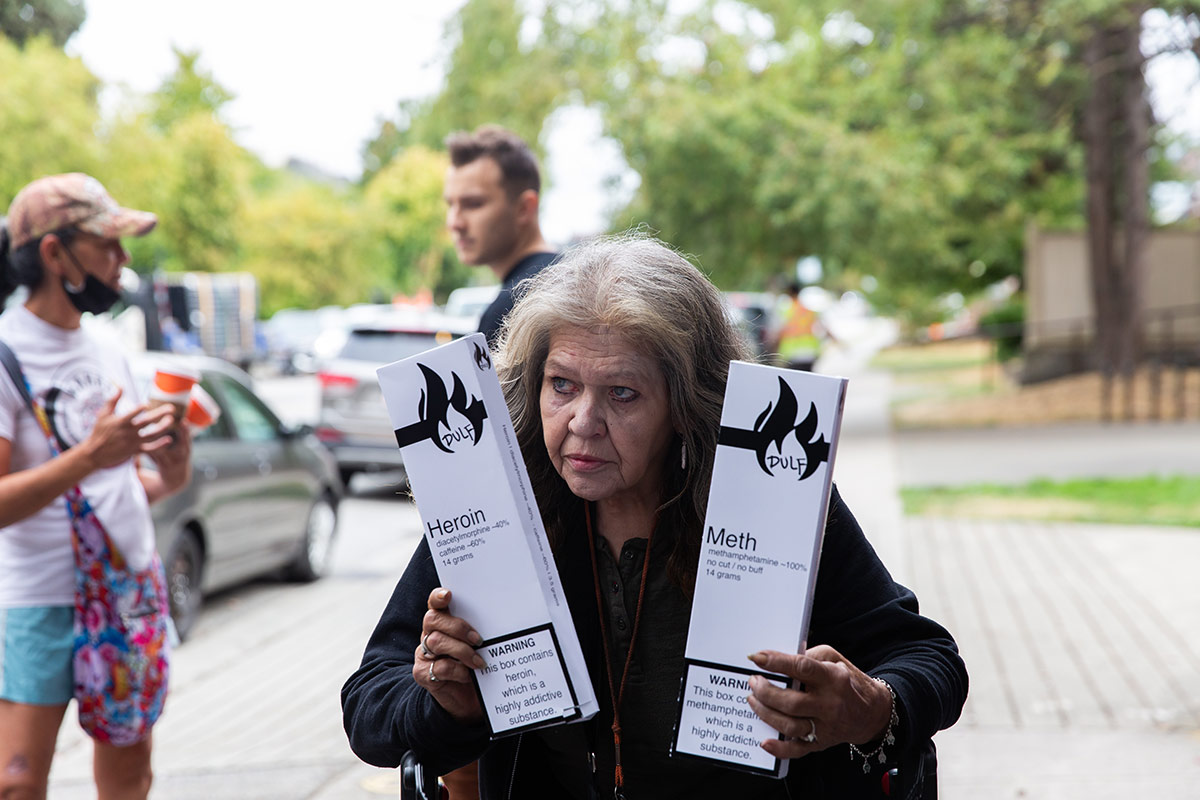

In spring of that year, the two formed an organization called the Drug User Liberation Front, or DULF, to push for changes to the way people in Canada think about and use drugs.

The group isn’t just advocating for change. They’re breaking Canadian laws to show how drug use could be safer if people had legal access to tested, untainted drugs — and they’re working to create a compassion club model for users of heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine.

“We still aren’t sanctioned, and I’m constantly afraid of arrests,” Nyx says. “Nothing about what we’re doing is legal.”

British Columbia first declared a public health emergency because of a rise in opioid deaths on April 14, 2016. This emergency has never been lifted.

The grab-bag of statistics related to the crisis offers nothing but grief and heartbreak.

B.C. has the highest rate of drug toxicity deaths in Canada, at 40 deaths per 100,000 people — a higher rate than Ohio or Pennsylvania. Across Canada, overdoses have killed 21,000 people since 2016. Currently, around seven people die every day of drug toxicity in B.C., up from six last year, and drug toxicity deaths are now the number one killer of people aged 18 to 39.

After three years of expanding harm reduction services like overdose prevention sites and access to naloxone, a drug that can reverse opioid overdoses, the number of deaths in B.C. finally started to drop in 2019.

But all that progress was erased when the COVID-19 pandemic hit Canada in early 2020. With borders closed and the movement of goods backlogged, the illicit drug supply has become more dangerous with every passing month.

Since 2016, the rising number of overdoses has been driven by fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that has largely replaced heroin in the illicit opioid supply, and benzodiazepines, which increase the risk of fatal overdose when combined with fentanyl.

Stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamines have also increasingly been contaminated with fentanyl.

This has led to a situation where more people have died of drug toxicity than COVID-19 during the pandemic in B.C. — 3,389 in total between March 2020 and October 2021, compared to 2,656 deaths from COVID-19. Drugs sold on the street today are so dangerous that users risk death every time they consume them.

While many people in B.C. first learned of the increased risk of overdoses after Patricia Daly, the chief medical health officer for Vancouver Coastal Health, briefed Vancouver council in April 2020, Nyx and Kalicum were seeing the worsening situation play out on the streets of the Downtown Eastside — and they decided to take action.

The idea was to find a dealer who had heroin and to test it to make sure it wasn’t contaminated. But that attempt didn’t go very well: a friend of Nyx and Kalicum’s bought heroin, but when Kalicum tested it, he found it had fentanyl in it. When the friend tried to get his money back, he was attacked with bear mace.

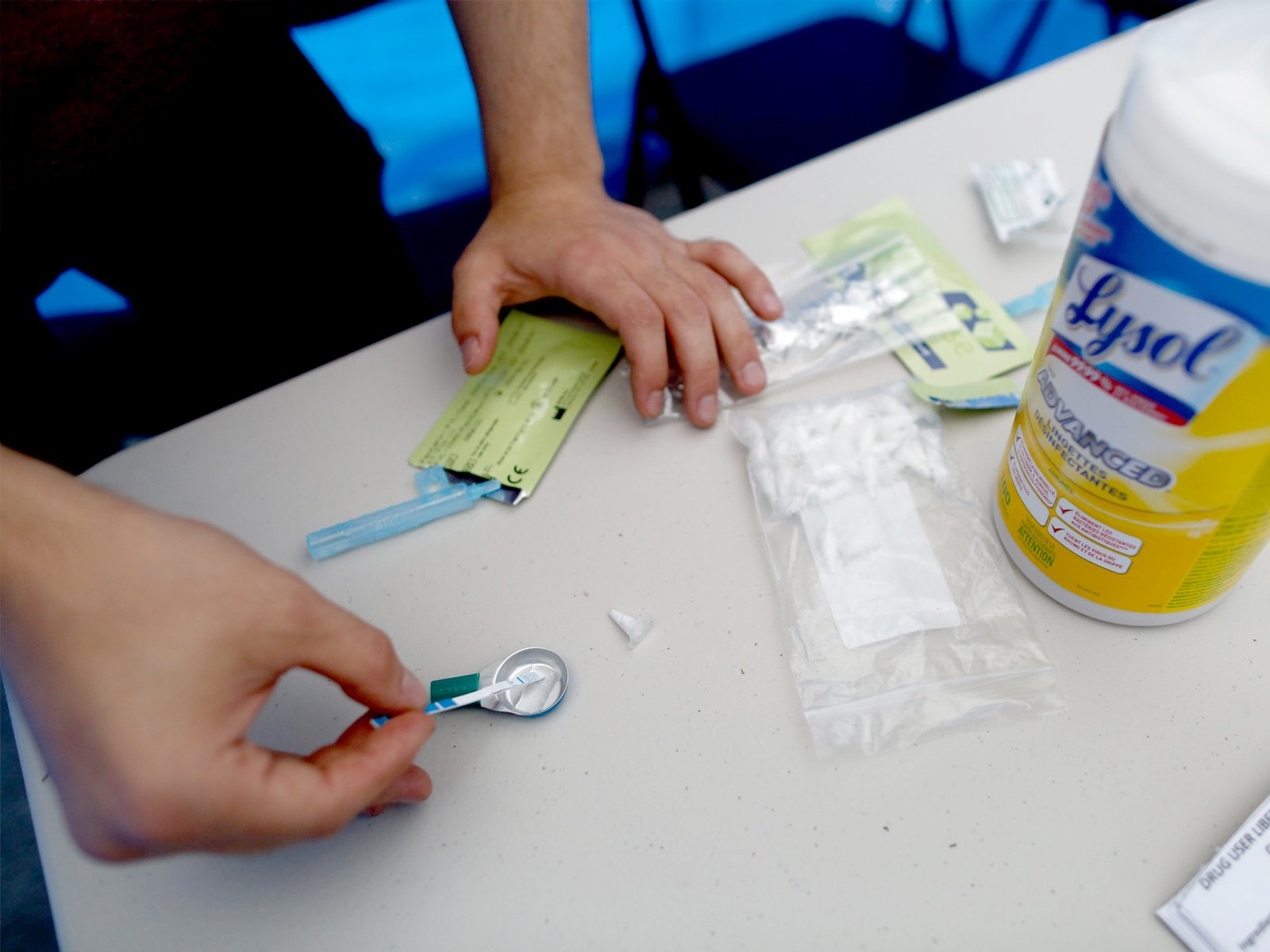

Nyx and Kalicum were able to purchase cocaine from a local dealer, which they tested and found to be uncontaminated with other drugs like fentanyl, carfentanil and benzodiazepines. On June 23, 2020, they held their first event in the Downtown Eastside, handing out 280 doses of cocaine.

The event went relatively smoothly — the biggest problem, Nyx quipped, was letting attendees have access to the open mic. No one overdosed. And Nyx and Kalicum didn’t get arrested.

The ‘birthplace of prohibition’ — and activist intervention

In December 1988, a donor offered to buy several hundred new needles for a Downtown Eastside group led by a former drug user named John Turvey. Turvey put the clean needles in a backpack and started handing them out as he walked around the streets and alleyways.

The point of the program, Turvey explained to the New York Times, was not to decrease drug use, but to save lives in an era when HIV, then a death sentence, was swiftly spreading.

The “war on drugs” — an approach that emphasizes the creation and enforcement of laws against making, selling and consuming certain substances — is often viewed as a largely American endeavour. But Canada has its own deep history of drug prohibition.

The Canadian Drug Policy Coalition calls Vancouver “the birthplace of prohibition,” because the federal government introduced a law to prohibit opium in response to a racist riot that targeted Chinatown in 1907. In 1911, cocaine and morphine were also restricted for non-medical use, and penalties for drug trafficking were increased.

In the decades that followed, using drugs was seen as a moral failure — a “vice” — and abstinence the only way out of the grip of addiction.

Though North America’s short-lived prohibition against alcohol in the early 20th century was short-lived, the prohibition against drugs has lasted for decades. And pretty much every effort to make using drugs less dangerous under prohibition has required drug users, advocates or health-care workers to break the law.

In San Francisco in the late 1980s, harm reduction activists were arrested after using baby carriages to hide clean needles. Turvey was also very much breaking the law when he first started handing out clean needles in the Downtown Eastside.

Though this has now changed in Canada and some American states, in the 1980s and 1990s it was common for legal needle exchanges to limit the numbers of needles they would hand out, or to require drug users to exchange a used needle for a clean needle.

In fact, a needle exchange run by Turvey in 1995 was criticized for its role in an HIV outbreak because the exchange limited the number of needles it would distribute, according to media reports from the time.

Two unsanctioned safe injection sites operated intermittently in the Downtown Eastside in the mid-'90s and early 2000s before Insite, North America’s first legal safe injection site, opened in 2003.

The second such site, the Dr. Peter Centre in Vancouver, got the OK to open in early 2016. But it wasn’t until overdose deaths started rising sharply in 2015 and 2016, and Vancouver activists broke the law again to set up unsanctioned overdose prevention sites, that government rules were changed to allow the sites across B.C. and other parts of Canada.

Compared to Insite, which is staffed by nurses, overdose prevention and safe consumption sites are a lower-barrier model where trained volunteers and employees provide first aid if someone overdoses. Today, over 30 such sites are now in place across Canada, although some still face pushback from residents and politicians.

The same spirit of law-breaking for the greater good can be found in the story of cannabis in Canada. Before it was legalized in Canada in 2018, people who used the drug for health conditions purchased it illegally from compassion clubs.

“The whole ethos of the compassion club in the old day was, this was a civil disobedience,” says Donald MacPherson, executive director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. “It was bringing medicine to patients.”

Kalicum and Nyx see themselves as part of this bold and desperate tradition. Though it’s estimated that deaths in B.C. would be twice as high if overdose prevention sites and other harm reduction services were not available, accidental deaths due to drug toxicity are still on the rise.

Like the drug user activists before them, they say they have no choice but to break the law in order to save lives.

‘The summer I turned 21, I responded to over 100 overdoses’

Nyx and Kalicum, who met in 2019 while organizing a conference on safe supply, both struggled growing up — Nyx in Ontario, and Kalicum in B.C.

When Kalicum started getting into trouble as a young teen living in Nanaimo, a community group stepped in and offered to send him to a boarding school for disadvantaged kids near Chicago, an experience that set him on the path he’s on today.

By age 20, he was at university studying chemistry in Nanaimo. One day, he saw a television news story about how many people were dying of overdoses.

“I was like, ‘That’s crazy, that’s so bad — I can’t believe no one’s doing anything about it,’” he says.

Kalicum met with a city councillor who also wanted to do something about the problem, and he got involved helping to support an overdose prevention site that operated from a parking lot at Nanaimo’s city hall.

Later he worked for PHS Community Services Society in the Downtown Eastside. The organization runs supportive housing and overdose prevention sites in Vancouver and Victoria and made history when it opened Insite.

Kalicum described his experience working for PHS to Vancouver city councillors last fall as they prepared to vote on a motion to support DULF’s compassion club model for heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines.

“The summer I turned 21, I personally responded to over 100 overdoses and encountered multiple dead corpses of people who were found too late to be saved,” Kalicum told the council. “People from all walks of life, all ages are exposed to the risk of this unregulated market.

“Perhaps the most memorable of these interactions were multiple instances of parents asking me to test the drugs which maybe had killed their child. Usually, what their child thought was MDMA was N-ethylpentylone, which typically results in death when taken as an MDMA-sized dose.”

N-ethylpentylone is a drug that is similar to MDMA, also known as ecstasy, but is three times stronger than MDMA.

Like Kalicum, Nyx’s teen years were turbulent — and led her to work in harm reduction.

“There was nothing to do where I lived,” Nyx says, “so we’d smoke weed and break shit and be fucking morons and play loud music and go see punk music and do drugs.”

Growing up in a Toronto suburb, Nyx did drugs, got in trouble with the police and couch surfed at friends’ places. She’s transgender, which her family didn’t accept. In her last year of high school, she buckled down to make the grades and get into university and ended up studying at the University of British Columbia. It was an escape route, Nyx says.

After graduating, she worked at shelters and supportive housing run by RainCity, a Vancouver-based organization. For a few months, she worked at the BC Centre for Disease Control, but she says her “radical” style wasn’t a great fit for the government agency: “They fired me.”

Nyx plays in more than one punk band and keeps an array of sunglasses and bowties by her front door. For a drug handout in April, she dressed as a cartoon revolutionary, complete with a black beret and owlish dark sunglasses. For a protest in front of city hall in July, she donned a Willy Wonka costume and handed out heroin and cocaine alongside Coun. Jean Swanson.

“Someone’s got to go insane,” Nyx explained. “If everyone kept the same way of thinking, do you think anyone would dress up like Willy Wonka and mail the police giant golden tickets and hand out heroin in front of the police station? That’s not a sanity move.”

Nyx has always used drugs — to have fun, to escape, to stay up, to fall asleep. To be able to work 16-hour days to write grants and run naloxone training sessions and organize meetings with politicians.

But no matter how hard she works, the people around her keep dying. Drugs can help her fall asleep, but they can’t stop the nightmares.

“I feel like everyone else is dancing around,” she said, “while I’m like… there are corpses everywhere.”

‘Please help me, I’m going to die’

Drug users in Vancouver have run their own informal compassion clubs in the past, but the idea to start a more organized program emerged after Nyx and Kalicum read a paper published by the BC Centre on Substance Use in 2019.

They assumed someone — the centre, or maybe PHS — would use the detailed model outlined in the paper to set up a program that would give drug users some sort of certainty about the drugs they were taking. But that didn’t happen.

So they decided to do it themselves.

After their first drug handout in June 2020, which involved drugs obtained via the local illicit market, Nyx and Kalicum tried out the dark web. It worked: the drugs, shipped to a post office box in Vancouver, tested as pure forms of what the sellers said they were.

At three more events throughout 2021, they handed out cocaine, heroin and meth to people who were over 18 and already using drugs.

After running the events successfully and safely, Nyx and Kalicum realized the model could be scaled up. They hadn’t been arrested, and there was support from the public, including donations to purchase the drugs.

“We learned that it was politically palatable,” Kalicum says. “The response from the public and the police not responding, I think really spoke to this as something that we could do.”

Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act allows the federal health minister to issue an exemption from any part of the legislation “for a medical or scientific purpose or is otherwise in the public interest.”

Getting Health Canada to grant an exemption from the act paved the way for Insite to open, and now DULF is also trying to get an exemption to run a sanctioned compassion club.

DULF’s application for an exemption, submitted to Health Canada on Aug. 31, outlines how the compassion club would work. Organizers would still get their drugs from the dark web until a legal, domestic source for drugs like heroin becomes available. Those drugs would be tested and stored in a secure place. Volunteers or staff would ensure that all the members of the compassion club are over 18 and currently use illicit drugs.

The tested drugs would be repackaged and clearly labelled so drug users would know what they were taking. The packaging DULF has proposed would resemble cigarette packaging in Canada, with warnings about the addictive nature of the drugs and to keep the substances away from children and pets.

“In full operation, the screening process will also be used to determine other needs that are not being met by club membership, such as assistance to navigate social support systems or accessing recovery/detox services,” the exemption request adds.

The pilot program DULF has proposed would be open to 200 people and would initially last for 15 months.

But as DULF has pushed to make the compassion club model legitimate, the source of the drugs they’ve been handing out has become a sticking point for some potential supporters.

The dark web is an encrypted network that allows people to access the internet anonymously; it first came to public prominence in 2013 when the man behind Silk Road, a large online marketplace for illegal drugs, was arrested and charged with drug trafficking, money laundering and computer hacking after an FBI investigation.

The anonymity of the dark web, which relies on cryptocurrency for payments, can be used to hide criminal activities — some, like purchasing drugs, may be broadly publicly palatable, but others, like child pornography or terrorist activities, are definitely not.

“You had mentioned in your answers to Coun. Swanson that you have no interest in supporting organized crime,” Melissa De Genova, a Vancouver councillor with the centre-right Non-Partisan Association, asked Nyx during a council meeting on Oct. 6.

“I’m wondering though, if the illicit products that you’re purchasing are coming from the dark web — do you acknowledge that you are supporting organized crime?”

De Genova wasn’t the only city councillor to raise concerns about the dark web during the council meeting. Despite those concerns, De Genova voted along with other councillors to unanimously support DULF’s exemption application to Health Canada.

But her persistent questions about the dark web’s role in facilitating child pornography and sex trafficking have continued to rankle Nyx, who has accused De Genova of further stigmatizing people who use DULF’s compassion club.

The appearance of a button calling De Genova a “pumpkin-headed fuck” and a shirt reading “Melissa Spaghetti De Genova” for sale on a site selling merchandise to support DULF prompted condemnation from other centre-right politicians. (The pin and shirt are no longer listed on the site, and DULF apologized for the stunt.)

Nyx and Kalicum say they’d rather get drugs for the compassion club through legal sources: domestically produced heroin and cocaine that is manufactured in Canada and regulated by the government. That would undercut organized crime, they say, by sourcing regulated drugs that are cheaper than the substances being sold on the street.

But that regulated source doesn’t exist yet. The one tiny prescription heroin program that operates in Canada, at Crosstown Clinic in Vancouver, imports the pharmaceutical-grade drug, which is also known as diacetylmorphine, from Europe.

A domestic source could be in place soon, however. In October, Fair Price Pharma, a non-profit company set up by Dr. Perry Kendall, a former B.C. provincial health officer, imported the materials needed to make diacetylmorphine for the first time in Canada.

The company plans to lease industrial space in the Lower Mainland and manufacture an inhalable form of diacetylmorphine. That locally made prescription heroin would then be shipped around the province to clinics running their own safe supply programs.

Under Canada’s current drug laws, it would only be possible to give this diacetylmorphine to people who had a prescription from their doctor. But Dr. Martin Schechter, a co-founder of Fair Price Pharma, said he’s written a letter of support for the compassion club model. If DULF gets an exemption from Health Canada, he says, Fair Price Pharma could supply diacetylmorphine to compassion club members.

Schechter, a professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia, was involved in the NAOMI clinical trial, which predated the prescription heroin program and ran at Crosstown Clinic from 2005 to 2008.

The NAOMI trial was the first of its kind in North America, involving participants who were addicted to illicit opioids and were not able to successfully use other forms of addiction treatment. Some participants were given diacetylmorphine, while others were given methadone.

The results of the trial found that the participants who’d been prescribed diacetylmorphine had improved physical and mental health. The study also found that those who had been prescribed diacetylmorphine were 62 per cent more likely to remain in addiction treatment and 40 per cent less likely to use illegal drugs and commit crimes to support their drug habit than participants who were treated with methadone.

But while a small number of trial participants continue to receive diacetylmorphine, the model has never been expanded in Canada because of what Schechter says are purely political reasons.

While the prescription opioids Dilaudid and hydromorphone have increasingly been prescribed to provide drug users safer alternatives to illicit opioids, drug users have been frustrated by the comparatively slow pace of efforts to provide a wider range of drugs they say should be made available to drug users.

Nyx, Kalicum and other advocates are pushing for access to heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines that don’t contain fentanyl, benzos or other adulterants responsible for toxic drug deaths.

Unlike the way diacetylmorphine was prescribed and carefully studied during the NAOMI trial, Schechter said the compassion club model is untested. But he thinks it’s worth trying as a pilot project.

“I think that DULF and others should get these exemptions and they should be subject to evaluation to demonstrate that they do indeed work,” Schechter says.

“Because six people are dying every day, and drug prohibition has been a massive failure. Everybody knows that. It’s just a question of whether you’re willing to say it out loud. And so I think we have to try new things.”

While Schechter is frustrated that access to safe supply is limited, Dr. Julian Somers is worried about the increasing acceptance of the idea. Somers says comprehensive treatment for addiction, which includes housing and other supports, is chronically underfunded by governments.

Poor people who can’t fund their own treatment are the ones who miss out, Somers said, and he fears that “safe supply” will become the only option available for the most disadvantaged drug users.

“There isn’t a community where an increase in prescribing works,” says Somers, a psychologist and professor in the health sciences department of Simon Fraser University. “We are so preoccupied with prescribing our way out of the problems we face.”

Dr. Vincent Lam, a doctor in Toronto, recently wrote in the Globe and Mail that he can’t reconcile the potential harms of prescribing hydromorphone to replace someone’s need for fentanyl or heroin.

Lam wrote that he’s heard from some drug users that a prescription has helped turn their lives around and avoid dying from the contaminated illicit supply, but he’s also spoken to others who say the availability of prescribed alternatives to illicit supply has pulled them back into addiction.

“Patients of mine who were free of illicit opioids for years now struggle with hydromorphone, which they are buying from those to whom it is prescribed,” Lam wrote.

Somers and Lam say there is little hard evidence that safe supply is beneficial for people who use drugs, and they object to the term itself. “There’s no such thing as safe supply — that’s a marketing term,” Somers says.

Schechter disagrees. Several studies, he says, have shown that prescribing diacetylmorphine is effective for people who haven’t had success with methadone or suboxone, drugs that are prescribed to prevent opioid withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

“Not only are they more effective, but they cost less,” he said, “because when you use things like diacetylmorphine, crime goes down, hospitalizations go down.”

In an unpublished opinion piece written to respond to Lam’s Globe and Mail article, Nyx and Kalicum said Lam misunderstands the purpose of safe supply: to “save lives amid a toxic, unregulated supply of drugs.”

“Meaningful change cannot happen without addressing the source of these deaths: the unpredictable drug supply created by prohibition,” Nyx and Kalicum wrote. “The scale and urgency of this crisis requires new approaches, and we ask our colleagues in medicine and in enforcement to heed that the times are changing.”

Though some doctors have raised concerns, many support increasing access to safe supply.

Vancouver Coastal Health, B.C.’s second largest health authority by population, supports DULF’s exemption application and has pledged to help implement the compassion club if it’s approved. The proposal is also supported by the BC Centre on Substance Use and the B.C. First Nations Health Authority.

Vancouver city council — including De Genova, the councillor who repeatedly voiced concerns about DULF buying drugs using dark web marketplaces — voted unanimously to endorse DULF’s exemption application.

Sonia Furstenau, a B.C. MLA and the leader of the provincial Green Party, has also said she’ll support the compassion club idea and will work with MLAs in other parties to build support for the exemption request.

Back in the Gastown apartment with the prowling cat, Nyx has managed to order some drugs, but the experience has mostly been frustrating. She wishes the politicians and bureaucrats who have the power to change things could feel the urgency she does every day when people overdose on the street, or see the pleas that face her every time she opens her email.

“My inbox is filled with messages: ‘Please help me, I’m going to die,’” Nyx says.

So far, she has no answers. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: