Kaye Kaminishi spent the first day of his second century much the way he did the final day of his first — by answering telephone calls of congratulations.

It takes a lot of energy to celebrate a 100th birthday.

Kaminishi belongs to a fraternity of athletes once cheered, then reviled, then forgotten and ignored. Decades passed before the story of the Japanese Canadian baseball team of Vancouver was rediscovered.

The Asahi were the pride of Vancouver’s Little Tokyo neighbourhood until war led to the dispossession and removal of people of Japanese ancestry from the city.

A slight, soft-spoken man, Kaminishi is ambassador for a team that played what would be its final game more than 80 years ago. He is the last of the Asahi.

In recent years, he has appeared in a Heritage Minute and been present for Canada Post’s unveiling of a commemorative stamp celebrating the team.

To represent his old team is a responsibility he never asked for and certainly could never have imagined as a young man. He had only just made the team and his future on the diamond was uncertain. It is a burden he handles with grace and a sense of bemusement so many now want to know about a team long ago forcibly dissolved.

“The Asahi ball club was about sportsmanship and playing fair,” he told me recently.

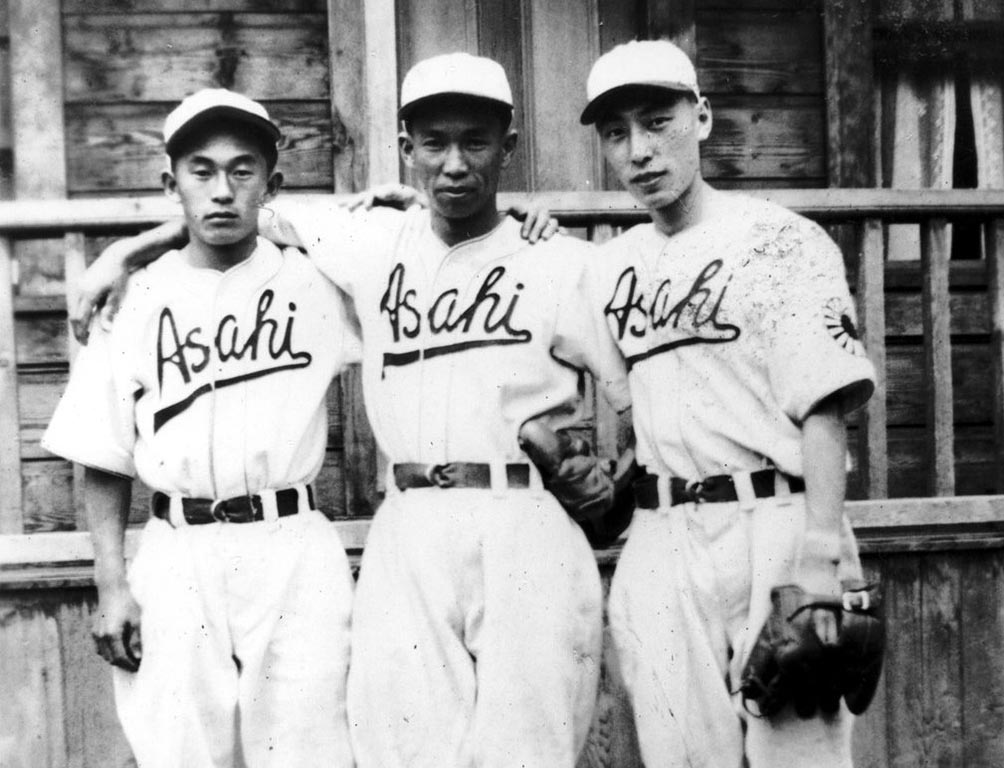

Kaminishi was still a teenager attending high school when his skills — speed on the basepaths, an ability to bunt and an adept glove combined with the willingness to follow manager Roy Yamamura’s instruction “if you can’t stop by glove, stop by chest” — earned him a coveted spot on the Asahi roster. He wore a white uniform with the team name spilling in Coca-Cola script across his chest in a vibrant red. On the sleeve was a modified rising sun logo, the team name — Asa (“morning”) and hi (“sun”) — rendered in a symbol representing his ancestral homeland.

Whatever plans he had for the future were interrupted by the Second World War and the internment of Japanese Canadians. He did not get to manage the family business that was his inheritance and he did not get to discover what kind of ballplayer he could have been on the diamond.

Asahi baseball uniforms did not carry a number. Kaminishi would get his number after internment when the government of his homeland registered him as enemy alien No. 01188.

Koichi Kaminishi was born on Jan. 11, 1922, the day after his mother’s 23rd birthday. Kayano Takehara was born in Hiroshima and arrived in Canada not long before a Jazz Age romance with businessman Kannosuke Kaminishi resulted in a son. The boy was sent to Japan to live with a maternal aunt. Takehara listed her occupation as housemaid for Kaminishi at the Dunlevy Rooms, a rooming house at the corner of Dunlevy Avenue and Powell Street.

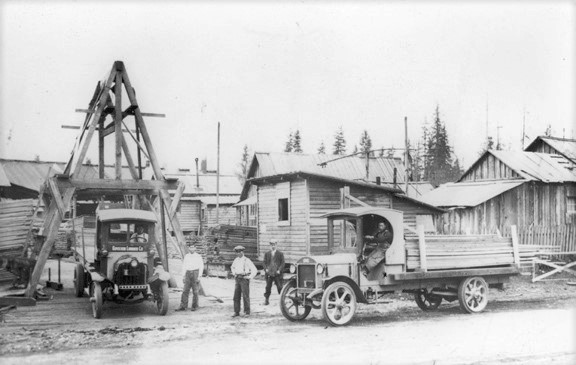

The senior Kaminishi was an astute businessman, holding majority ownership of the thriving Royston Lumber Co. on Vancouver Island. Kaye remembers his father as “a kind person.” A dapper man who wore three-piece suits and a fedora, he also smoked a pipe. A camera enthusiast, he took still photographs and made home movies of his enterprises, also capturing scenes from several trips to Japan. He dabbled in property, ran a rooming-house business and lent money to others in the community for their own ventures.

On Feb. 1, 1933, Kaminishi died at home of a heart attack. A three-hour funeral service was held at the Hompa Buddhist temple, where he served as president. A cavalcade of cars followed the hearse on a slow journey to Mountain View Cemetery for interment.

Six months later, the Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Asia docked in Vancouver carrying on board the 11-year-old boy and the mother who had come to fetch him.

They lived at the Dunlevy Rooms, occupying several rooms on the second floor of a 60-unit building home to loggers and labourers. The boy was enrolled with younger pupils in Grade 3 at Strathcona Elementary, a frustrating and embarrassing circumstance for a bright student who was held back from his age cohort because he did not yet speak English.

A teacher at the school did not care to learn his Japanese name. “I am going to give you a new name,” the teacher told him. “From now on, you are Kaye.”

The boy moved up a grade every few months as his English proficiency improved. He also attended Japanese-language school after class, helped his mother with chores at the rooming house on Saturday, and played baseball, soccer and lacrosse whenever he got the chance.

His mother, like other Issei immigrants in the neighbourhood, did not need English to function in a community in which most every product and service was available in her native language.

A focus of pride was the Asahi baseball team, which played at the Powell Street Grounds, known today as Oppenheimer Park. The team of Japanese Canadian players was formed in 1914, a few years after residents successfully defended their neighbourhood from a rampaging mob of white supremacists.

The amateur team played in local commercial leagues. Physically smaller than their opponents, the Asahi developed a style of play which came to be known as “brain ball.” They relied on slick fielding, daring baserunning, audacious base-stealing, precision bunting and a reliance on strategy over brawn. They won more than one game in which the opposing pitcher had held them hitless.

When the Asahi toured Japan in 1921, they brought with them a handful of white players from rival teams, showing baseball could bridge divisions between communities.

The Asahi won the Terminal League championship in 1926, earning promotion to the city’s Senior League at Athletic Park, where they would be less successful against tougher competition. By then, the Asahi’s entertaining style of baseball earned them a following among fans without connection to the Japanese Canadian community. Players such as Tom Matoba, Ty Suga, Nag Nishihara, the Kitigawa brothers (Mickey, Eddie and Yo Horii), and Roy Yamamura, known as the Dancing Shortstop, were household names in Little Tokyo and throughout the city.

The club developed a feeder system of youth players on teams known as Clovers, Beavers and Athletics, all the young players hoping to someday play for the Asahi.

Daily life in Little Tokyo seemed to come to a halt when the Asahi played a home game at the Powell Grounds. The park had a modest wooden grandstand surrounding home plate with spectators standing along the foul lines and, during some big games, even crowding onto the outfield grass. When he wasn’t at the park with friends, Kaminishi watched the action from his family’s apartment on the second floor of the Dunlevy Rooms.

“Before I joined the Asahi, I watched every game the Asahi played,” he once told an oral historian.

In 1939, at age 17, while still a student at King Edward High, Kaminishi earned a coveted roster spot on the parent club.

“I was so happy and nervous,” he said. “I was so excited I couldn’t sleep all night” the day before his debut.

The five-foot, five-and-a-half inch, 120-pound utility infielder mostly played third base. He saw only spot duty on a veteran team coming off a triple championship season, having won the Burrard and Commercial league titles in Vancouver, as well as the Pacific Northwest title against other teams of Japanese ancestry along the coast.

In one of his first at-bats at the Powell Grounds, Kaminishi lashed the ball beyond the left fielder. As the ball bounced and rolled towards Jackson Avenue, he was certain he had a chance for at least a triple, or perhaps an inside-the-park home run. A stumble between first and second base forced him to settle for a double, a rueful memory to this day.

He also remembers the Asahi benefiting from a home-team advantage.

“When we hit the ball near the crowds (on the outfield grass or along the foul lines), they barely moved,” he said with a laugh. “When they hit the ball to the same place, the crowds got out of the way so we could catch.”

After the games, the team retired to local cafes, where a fan might buy a player a steak dinner. After one game in which the Asahi hit poorly, Kaminishi was slipped $5 with instructions to buy a better bat.

His role limited on the Asahi, who still relied on older veterans, the infielder got seasoning by also playing for a team sponsored by the same Buddhist temple for which his father had served as president.

At the start of the season, he was given an Asahi uniform in flannel. At the end of the season, he was presented a purple wool sweater with a gold letter A.

Kaminishi’s plan was to complete high school studies before taking over the family’s business after reaching the age of majority. His father had willed the entirety of his state to his son, while naming Kayano (“the real mother of my son,” as the will stated) as executrix. In the meantime, the lumber business was run by general manager George Uchiyama.

In the summer of 1941, Kaminishi and his mother visited relatives in Japan, a journey taken at a time of worsening global tensions. The governments of Canada and Imperial Japan placed economic restrictions on the other’s nationals. It became all but impossible to return home. At last, Kayano booked passage aboard the liner Hikawa Maru, which arrived in Vancouver at 4 a.m. on Nov. 1. It turned out to be the last ship to leave Japan for Canada before the outbreak of war.

(Among the Hikawa Maru’s 212 passengers was Lidia Fruchs, a 21-year-old office clerk who was one of 2,100 Polish Jews who fled the Nazis occupying her country to find temporary sanctuary in Lithuania, where Japanese acting consul Chiune Sugihara provided visas. In Vancouver, she met and married mechanical engineer Stefan Goldsztein, another refugee from Poland. The couple’s families were murdered in the Holocaust. Lydia Golston, as she was later known, lived until age 94.)

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7 and, later in the month, on Hong Kong, brought the Pacific war to British Columbia. Under the War Measures Act, anyone of Japanese ancestry was declared to be an “enemy alien.” Some 21,000 people were to be forcibly removed from the coast. Businesses were seized and motor vehicles, as well as fishing boats, cameras and radios, were ordered surrendered.

The Kaminishis’ Royston Lumber Co. turned over a lumber hoist, six lumber trucks, two carriers, and the manager’s personal 1941 Packard Eight. The vehicles were delivered by the RCMP after a convoy from upper Vancouver Island arrived in Victoria. Some of the confiscated vehicles carried license toppers with patriotic slogans such as “‘V’ for victory” and “There’ll always be an England.”

Kaminishi avoided reporting for removal for two months, as he sold the rooming house business and otherwise tended to the family’s affairs. He managed to store one carton, five trunks, 12 cases and four flower baskets of personal effects, as well as a deer head, with a cartage company.

He and his mother were among community members who had enough money to negotiate assignment to what was called a “self-supporting camp” in East Lillooet. The two lived in hut No. 59 of a settlement of 62 tarpaper shacks lacking electricity and plumbing. The city boy needed to rely on carpenters in the camp to help build his hut. The winters were brutal and icicles formed inside the uninsulated homes. Yellowish-brown water was brought up by pail from the turbid Fraser River before being filtered through gravel, sand and charcoal. Kaminishi remembers water being constantly on the boil in a wood-burning stove that also needed steady attention.

Each hut was allotted a strip garden for their subsistence. St’at’imc people slipped into the camp without permission from authorities to sell salmon, a welcome addition to a limited diet. Internees were forbidden to leave the camp, so Lillooet merchants took turns taking orders from those with the money to pay. Even sporting equipment was purchased.

To keep people fit and entertained, a modest softball diamond was carved out of the flatland, a small wooden fence built around home plate. Kaminishi starred on the camp’s team and it was his idea to challenge the local townspeople to a friendly game. When the players crossed the bridge to Lillooet for the game, it marked the end of the camp’s segregation.

“Town people had never seen Japanese people before,” Kaminishi once told an interviewer, “so they are so scared.”

He was the sole Asahi veteran in East Lillooet. The players were scattered. Several wound up at Lemon Creek, where they challenged other camps in the Slocan Valley to a baseball tournament on Dominion Day, 1943.

During internment, the Custodian of Enemy Property informed the Kaminishi family of the disposal of their business and property. In 1940, Royston Lumber had been evaluated with $376,000 of liquid assets, while holding expansive timber rights for another 10 years. Kaminishi estimated the company was worth about $775,000. The Custodian informed him Royston Lumber had been sold for just $202,000. Kaminishi’s share came to just $14,200. He would be awarded five times as much after making a claim after the war, still far less than what his share was worth. “They sold it for nothing,” he laments to this day.

As well, two residential lots at the foot of Argyle Street in Vancouver along the interurban tracks were sold. The property, which could only be accessed by tromping through bush, was assessed at $1,630. The tenants, who were paying a $9 monthly rent, tried a lowball offer of $600, which the Custodian rejected, selling the land and buildings for $1,100 to a sawmill company. Kaminishi got a cheque for $937.93. He instructed the Custodian to buy a $1,000 Victory Bond. Their old rooming house was the scene of an RCMP raid on July 21, 1943. Police said they found owner Harry Szczerban in the process of dismantling a crude still, tossing a coil through an open window. The proprietor was fined $150 in police court the following day for violating the Excise Act.

After the war ended, the federal government wanted the internees out of the province. Some were ordered to Eastern Canada, while others moved to Japan, a land devastated by war and which some Canadian-born deportees had never before seen. Of course Kaminishi’s mother’s hometown of Hiroshima had been destroyed by an atomic bomb.

In 1948, Kaminishi moved to Kamloops, where he found work at a packing house handling fruits and vegetables, later working as a liquor store clerk.

Restrictions on the internees were not entirely lifted until 1949, four years after the war. By then, the Japanese Canadian community had been dispersed, their property sold for pennies on the dollar, their lives upended and changed forever.

Soon after, he married Florence Naoko Kobayashi of Okanagan Centre. The couple eventually owned motels in Kamloops and Hope. They had a girl and then a boy, quietly going about the business of raising a family.

The former Asahi players dispersed across the country. Ty Suga’s Montreal Nisei team won the city championship in 1949. His kid brother, Kiyoshi, who had been secretary and official scorer for the Asahi, played catcher.

Kaz Suga, another brother, spent two seasons with St. Jean of the independent Quebec Provincial League before helping the St. Jerome Lions win the Laurentide League title.

The catcher Ken Kutsukake played amateur baseball briefly before becoming a manager of teams playing out of Christie Pits in Toronto. In 1956, his Honest Ed’s Nisei team won the city’s senior championship. Ed Mervish, the team’s delighted sponsor, feted them with a banquet and presented each player a commemorative wristwatch.

Yamamura, the Dancing Shortstop, became known as Mr. Ump among the youths he adjudicated on Toronto sandlots.

Thirty-one years passed from what would be the Asahis’ final game in 1941 before the athletes had a chance to reunite. Some 300 fans and former players gathered at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto in 1972. A first attempt to establish an all-time roster of Asahi players, based on memories and newspaper clippings, counted 70 athletes.

An indefatigable campaign by Pat (née Kawajiri) Adachi, who celebrated her 101st birthday last year, promoted interest in the forgotten story of the Asahi. In 1992, she self-published a scrapbook about the team’s history and two years later she appeared at a festival at the old Powell Street Grounds with several former players, including Mickey Terakita, Katsukake, and, wearing his old uniform, Kaminishi. The event marked the first time in a half-century the Asahi livery appeared at the old ball park.

In 2003, Jari Osborne’s National Film Board documentary Sleeping Tigers included archival photographs and interviews with surviving players. That same year, the Asahi as a team were inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame followed two years later by the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame. By then, only a handful of former players were still alive, a roster that shortened with every passing year until today, when only Kaminishi survives, a last member of a storied team.

His old glove, Asahi uniform and purple sweater are among the team’s few artifacts to have survived the war. He donated his collection to the Nikkei National Museum in Burnaby, along with his father’s home movies.

Kaminishi’s early years were marked by two exiles; one as a child, another as a young man; one personal, the other political.

Unwanted then, he is celebrated now.

A widower for five years, he now lives in Vancouver for the first time since being forcibly removed in 1942. He celebrated his birthday with his son Ed, 67, a retired college instructor, and his daughter Joyce, 70, a retired elementary schoolteacher. It has fallen to this modest man, who insists he was no more than a benchwarmer for the Asahi, to represent his fallen teammates. He does so with humor and dignity.

He is making the most of his extra innings. ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: