Next Tuesday is Chelsea Poorman’s 26th birthday. Her family, friends and supporters plan to mark that day by putting up more posters in the hope that they’ll lead to information about what happened to the young Indigenous woman.

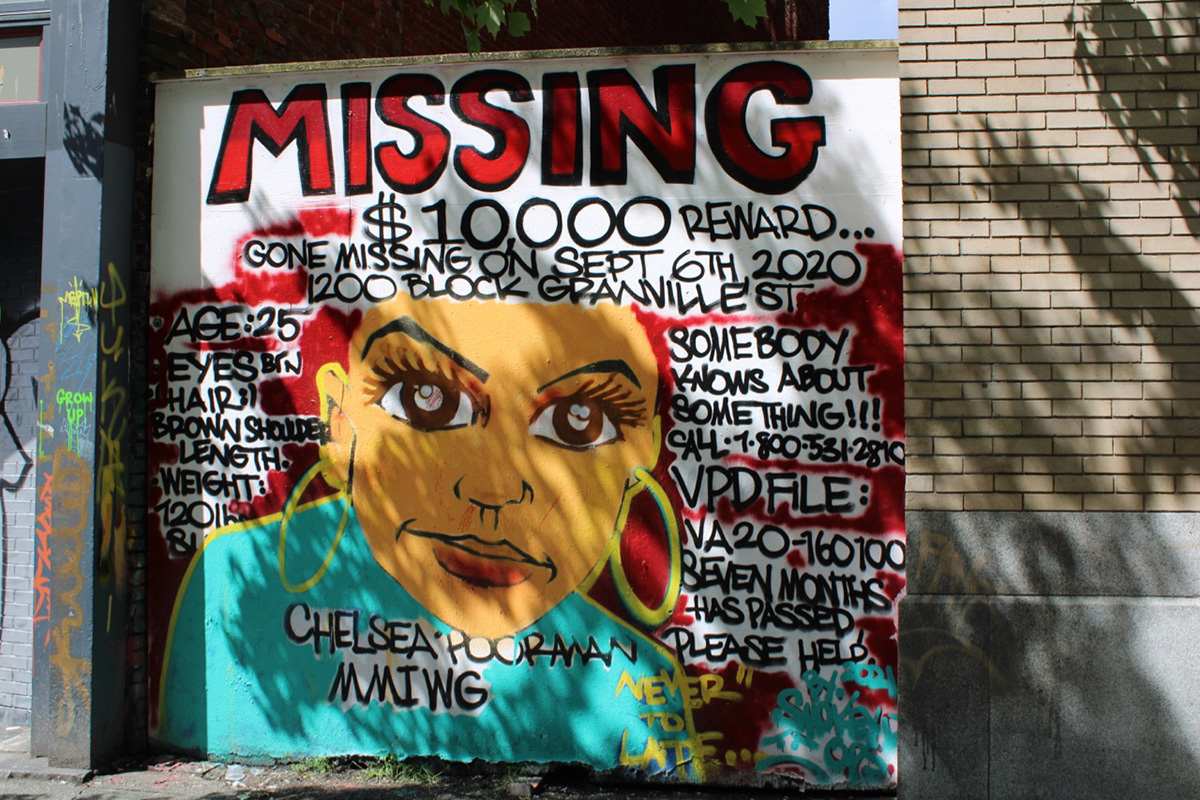

It’s now been just over a year since Poorman went missing in downtown Vancouver, but many people are still working to keep her case in the public eye through postering campaigns, community walks and graffiti art.

Chelsea went missing last September. Her sister Paige last saw her on Sept. 6, 2020, at a friend’s apartment at Granville and Drake, and her cellphone was later traced to Victory Square, 12 blocks north. The last message Paige got from her sister that night was about meeting “a new bae.”

Detectives with the Vancouver Police Department’s major crimes section investigated Chelsea’s disappearance, and Sgt. Steve Addison, a spokesperson for the VPD, told The Tyee officers remain hopeful and the case will remain open until Chelsea is found.

But Chelsea’s mom, Sheila Poorman, said there has been no new information for some time and the family has had to contact the police to keep up to date on the investigation.

“We don’t have any information, like absolutely nothing,” said Sheila. “How does somebody just vanish, disappear without leaving a trace?”

Addison said police are continuing to follow up on new leads and regularly review old leads to make sure they haven’t missed anything.

On Sept. 6, 2021, Sheila, Paige and other supporters walked from Granville and Drake to Victory Square, retracing the route they believe Chelsea took one year ago. The Poormans are members of the Kawacatoose First Nation in Saskatchewan, and in Saskatoon a childhood friend of Chelsea’s organized a walk to happen at the same time.

Chelsea’s family has been trying to fundraise to increase the amount of a reward, currently set at $10,000, for any information about what happened to Chelsea. There’s also a website and a Facebook page where supporters can find and download the missing person poster.

Sheila and Paige first reported Chelsea missing to police on Sept. 8, 2020. The young woman is especially vulnerable because she has a physical disability: Chelsea was in a car accident in 2014 and wears a brace on her left leg and a lifted shoe on her right foot. The accident left her with rods in her leg and arm, so she walks with a slight limp and can’t fully bend her left arm.

She would have difficulty walking without her brace, and Sheila fears that if Chelsea is being held somewhere against her will, she wouldn’t be able to escape without her brace.

The family still has questions about why police didn’t post a press release about Chelsea until 10 days after she was reported missing.

Police have said detectives take several factors into account before deciding whether to release information about missing people to the media, including a missing person’s mental health and whether attention from the news will be detrimental to their personal safety.

In Canada, Indigenous women and girls are five times more likely to experience violence than non-Indigenous women. On Monday, advocates across the country held a vigil for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls to continue to draw attention to the issue.

“I’ve been on so many searches with communities, individuals and organizations, because they don’t have the resources when their loved ones go missing,” said Chief Judy Wilson, secretary-treasurer of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs.

“They literally have to do it themselves.”

A National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls completed its final report in 2019, but the federal government didn’t release its action plan until June 2021 and many recommendations have yet to be funded and implemented, Wilson said.

She particularly called attention to the inquiry’s Call for Justice 5.6, which asks for more support for Indigenous victims of crime and family and friends of missing or murdered Indigenous people. That includes financial support, trauma and mental health support, guaranteed access to legal services, and legislated paid leave and disability benefits.

Sheila Poorman said that after the September walk for Chelsea, she and other family members were able to go to a retreat for families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, organized by the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.

“To meet the other families and know that we’re not alone in this — it was great to see and to hear their stories,” she said. “I was able to relate to each and every person who shared, and that was really powerful.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: