Angeline Pete, of Quatsino First Nation, is “fiercely protective, always eager to help others, and so strong, we never worried about her,” says her auntie, Cary-Lee Calder, in the opening of “Sacred and Strong: Upholding our Matriarchal Roles,” a new health report about First Nations women, girls, non-binary and Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer individuals living in B.C.

Pete, shares Calder, has been missing since May 21, 2011.

“Sacred and Strong” sets out to disturb the status quo of population health reporting. Data and lived experience are woven together to form a layered view into wellness journeys, says Dr. Danièle Behn Smith, deputy provincial health officer for Indigenous Health. Behn Smith is Eh Cho Dene of the Fort Nelson First Nation with French Canadian/Métis roots in the Red River Valley.

Launched July 29, “Sacred and Strong” is a partnership between the First Nations Health Authority and the Office of the Provincial Health Officer that follows in the wake of significant reports — the Truth and Reconciliation report, “Reclaiming Power and Place” and “In Plain Sight,” which detailed anti-Indigenous racism in the B.C. health-care system.

“There’s still so much work to be done to decolonize population health reporting, and to improve First Nations data governance,” Behn Smith says.

A 2007 report called “Pathways to Health and Healing” containing the statistics and data typical of a comprehensive report served its purpose, says Dr. Shannon McDonald, chief medical officer at FNHA — but community members didn’t see themselves represented in the report’s approach.

In contrast, Smith says, “Sacred and Strong” feels like a step in the right direction. “It’s a departure from the status quo, and the status quo is very colonial.”

The new report holds “space for First Nations’ ways of knowing and being, that really illuminates our different forms of knowledge, which are as valid and valuable as the western public health forms of knowledge — statistics, charts and the figures,” says McDonald.

“Sacred and Strong” was first launched to First Nations community leadership, following the principles of ownership, control, access and possession. This means First Nations control data collection processes in their communities: to own, protect and control how their information is used.

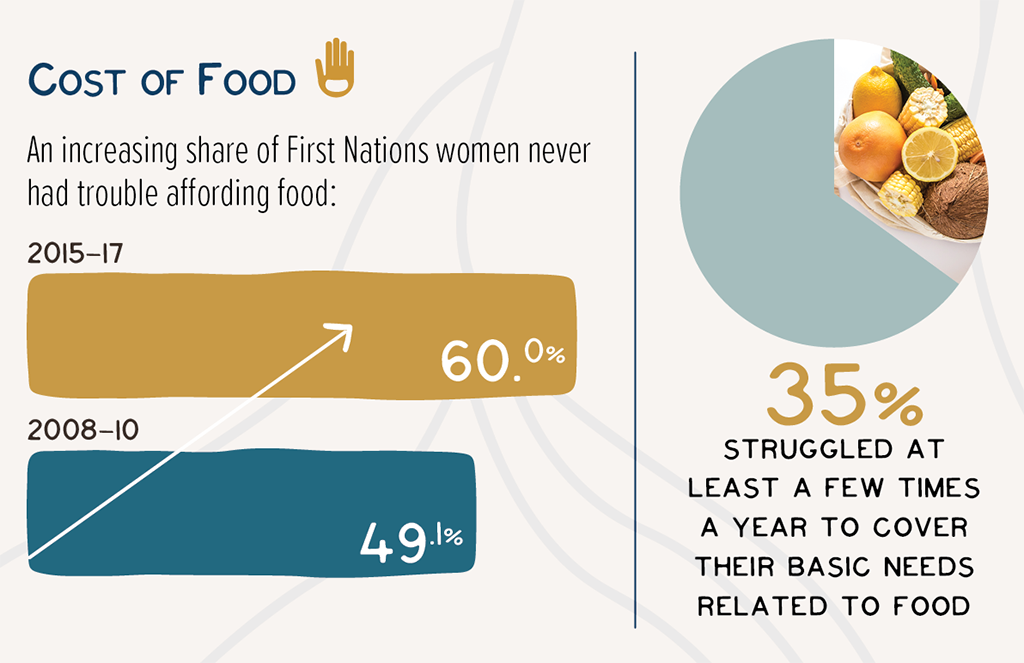

Data include positive trends — 72.1 percent of First Nations babies are a healthy birth weight, for example, and there has been an eight-per-cent increase in use of midwives as primary health-care providers. Other data showed areas of concern: 49.6 per cent of girls have experienced cyberbullying in the past year, for example, and 82.5 per cent of young Indigenous women are going to bed hungry due to lack of money for food.

After opening with Cary-Lee Calder’s tribute to her niece, “Sacred and Strong” continues with a dedication to missing and murdered women and girls and their families.

Celebrating the ways Indigenous girls and women are thriving, the report also seeks “to bring light where these systemic barriers continue to negatively impact their health and self-determination,” says FHNA. “It is also a reminder of the urgent need for collective action.”

“It is time for our Indigenous women to rise together in strength and unity and claim our space in this world,” writes Calder.

Calder also addresses political leaders. “Move reconciliation into action,” she says. “What are you doing to contribute to keeping Indigenous women safe and addressing systemic racism?”

“The women’s voices had to take precedence, we had to privilege the voices,” says McDonald. “And then we support them with what data we have.”

Behn Smith was crackling with excitement as she prepared to share the report with First Nations leadership before its public launch.

There was so much people wanted to tell, and share, says McDonald. “Women were looking for stories about coming-of-age ceremonies, and where is the story about widowhood? Where is the story about our matriarchal rules in the community?”

“It’s about creating spaces for us to be able to live our teachings again, without interference,” says Behn Smith.

“There was certainly a time where everybody’s great-great-grandmothers lived in a balanced way with their environment, and we’re just so far from that right now,” she adds. “And so, reciprocity at this stage is trying to shrink our western public health approach — to create space, to be led by FNHA and their knowledge keepers and First Nations leaders and communities.”

Two questions were posed to First Nations girls and women, says Behn Smith. “What do we need more of as First Nations to be healthy, vibrant and self-determining, and what do we need less of — what’s getting in our way?”

What emerged was a need for more of those deepest roots of wellness, she says. “Our language, our land, our teachings, families, communities, nations.”

And what do women and girls need less of?

“We need less social exclusion and white supremacy and racism,” says Behn Smith. “So the opposite of that is we need supportive mainstream systems across the board.”

The report-making process is mirrored in the cover artwork of Tiyaltelwet, Melanie Rivers, of Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation).

Tiyaltelwet began by inscribing a dedication beneath, setting an intention for the multimedia artwork.

“To all First Nations women and girls,” she wrote. “All of you. You are beautiful. You are loved. You are resilient. May you be free from pain and suffering. May you be safe. May you love yourself. May you be healthy. May you feel strong. May you find your roots and feel grounded, connected, supported.”

Layers of text, collage and paint create an intergenerational world. Roots that interconnect match the report’s use of “roots of wellness.”

The report is arranged according to life cycle, beginning with perinatal health and ending with elder wellness. Each life stage is organized into three parts: healthy, self-determining roots; supportive systems; and healthy minds, bodies, spirits.

Clea Schooner is a 22-year-old Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk), Nuxalk and Tsleil-Waututh woman.

“I get to see three different cultural aspects of mental health and the way that we cope,” she says.

“I definitely see, there’s no one nation struggling more than the other. It’s all just collective intergenerational trauma and you know, like people, we don’t all struggle the same. The grief and trauma translates in so many different ways to so many different people and it’s like that with each nation too.”

Schooner was diagnosed with complex PTSD at 16 and says her wellness journey began with an understanding that it was in her power to create a healing path. For her, this meant committing to learning all she could about western medical options and combining them with an Indigenous lens on well-being.

“I wanted counsellors, I wanted therapists. I wanted psychologists and psychiatrists and answers. I was in a city and I was so disconnected to my family and my homeland, that’s how I was coping,” she says.

“I had to do all of the work on my own. At 16, I was having to book my own psychiatry appointments. I had to really want to put in the work to heal. No one was forcing me to do this. It had to be my choice.”

Schooner grew up feeling very spiritually and culturally connected to everything around her.

“I was so close with my late great-gran,” she says. “She was a powerful matriarch who had a lot of intergenerational trauma, but she also had that balance of ancestral strength. Having that healthy role model in my life definitely inspired me to find that balance.”

She was told the story about two wolves fighting — one good, one evil. Her great-gran asked her: which wolf would win that fight? The meaning relates to focusing attention and energy on what you value.

While Schooner doesn’t see things in terms that are quite so black and white, she says the lesson teaches that the wolf who wins is the one you feed. This gave her a solid foundation.

Schooner sees her trauma as one wolf; the other wolf is her strength.

Maxwaks, Stephanie Bernard, a Kwakwaka’wakw mother who lives in her territory in north Vancouver Island, shared her experiences of the health benefits of supportive networks with the report.

After some rough teen years, Maxwaks says, she had her first son at age 20. Maxwaks had finished her first year of college, but says she was making some poor decisions at the time.

The birth of her son, she says, changed her life.

“I decided at that point that I needed to shift my path and change the direction of where I was going,” she says. “It was a combination of wanting to break the cycle of how I was raised and that nurturing, protecting piece of wanting to raise my children in a safe and caring environment.”

Maxwaks moved back to Port Hardy 13 years ago with her sons so that they could learn where they are from and she could care for her grandmother.

“My granny was always my saving grace,” says Maxwaks. “I spent a lot of time with her over the course of my life. She was very — just very humble. She had a calming nature about her. Completely non-judgmental and loving. I remember those beautiful qualities.”

Maxwaks feels fortunate to have had a supportive network. Looking over her journey so far, she sees the benefits of traditional family life — having aunties and grandmothers stepping in to help with children, and then children growing up to take care of their family’s Elders.

It was very important for Maxwaks to know her granny was always there for her.

“That stability, that unconditional love — it was so important to me and my wellness journey,” Maxwaks says. “She is definitely one of my biggest role models.”

Maxwaks’s granny had cared for her when her mother could not. As a baby, a child and teenager, and as a young adult.

The ripple effects of residential schools interrupting healthy families and communities is undeniable, says Maxwaks. Yet, she sees hope.

“If we could go back to those traditional ways, it’s going to make a big impact.”

Syex̱wáliya, Ann Whonnock is an Elder, and knowledge holder from Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation).

Syex̱wáliya embodies the matriarch role in her caretaking and using her voice to advocate for her loved ones.

“If something happens in my family, I’m usually the one that goes up so that I make sure and get their needs for that day. I do have that voice and that’s being a mom and a granny, taking care of my family in the best way I can.”

Syex̱wáliya knows the importance of seeing wellness from a holistic perspective. She describes how spirit and mind is intertwined with physical health.

One example she gives comes from early in the pandemic. “When the lockdown happened, after the first month, one of the leaders of a health services team realized the impacts. Stressed and low morale,” she says. Syex̱wáliya was invited to support the team, brainstorming weekly check-ins. At the end of their work week, they would gather in a circle to debrief, and ask for help. They shared Salish songs and prayers.

“Using our culture to hold us up during our work week, to close off together in a good way and leave with a light heart. Then we can re-energize over the weekend and come back Monday with that prayer,” Syex̱wáliya says.

“My hope for health care is that my family gets taken care of in a good way — that my grandchildren know they can go into a hospital and be given treatment that everyone else in the province gets and not be stereotyped because of who they are and where they come from,” she adds.

Syex̱wáliya is hopeful the health system can change.

“It seems like it has begun to change, especially since the ‘In Plain Sight’ report came out — and hopefully more, with this report.”

“Strong and Sacred” also calls for more data about Indigenous women and girls — region-specific data that reflect gender-diversity.

The report’s authors also plan to update it with information that is forthcoming, but not yet available — the impacts of COVID-19 and the opiate crisis are not yet quantified, for example. Updates will be added to the FNHA website.

The report ends on a note of urgency. The stories and data shared show “significant work is still necessary to eliminate and transform the colonial and racist foundations of systems at the root of these injustices,” it says.

“These colonial attitudes, policies and structures are the reasons First Nations women and girls continue to face challenges to their wellness and go missing from their communities. There could be no greater impetus for action than that,” it adds.

“We need our allies,” Syex̱wáliya says.

“Use your influence and where you are in your life to make a meaningful difference in the world — to say that racism and discrimination and violence against people of colour is not acceptable anymore.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: