Lucy Sager once bought a plane ticket for a woman in northern British Columbia who was trying to get into treatment for substance use and then get her children back.

Sager, who owns the All Nations Driving Academy in Terrace, had been teaching the woman how to drive. For the mother, completing treatment and getting a driver’s licence were steps that would show child welfare workers she was determined to be what they deemed a good mom.

While the woman originally planned to take the Northern Health medical bus, stay in a shelter, then take another bus to her ultimate destination for recovery support, Sager knew that wouldn’t be safe. The route travels Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert, and is known as the Highway of Tears for how many women have gone missing and murdered on it.

Sager couldn’t let her friend take the risk. So the plane ride was an investment, one that paid off.

“This Christmas was the first Christmas she’s celebrated with her kids not living in a shelter in three-and-a-half years, and she’s just finished her Grade 10, and doing her Dogwood, and she’s learning her language and she’s a great mom,” said Sager. “This is the testimony of what’s possible.”

When Sager started her driving school in 2017, she didn’t realize how many barriers would surface when it came to Indigenous people getting their drivers’ licences.

She knew from her previous job in construction that it was an important piece of the employment puzzle. But she didn’t realize that lack of a licence could mean life or death.

She recalls a young woman who went missing on March 21, 2020. Shaylanna Lewis was last seen walking south on Highway 16 near Masset, in her home territory of Haida Gwaii.

She disappeared walking down the highway. “And she had no licence,” said Sager, who had taught in the community just before the disappearance. She felt grief and shock when she heard the news.

Because of the urgency of the situation, Sager recently wrote a paper, endorsed by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, titled The Road to Reconciliation: UBCIC Discussion Paper on Drivers Licensing.

It’s a demand for ICBC, the Ministry of Public Safety and the Office of the Attorney General to not only take a clear look at the issues involved, but to take action.

In the report, Sager lays out the barriers some Indigenous people face when trying to get a driver’s licence; identifies nine articles from the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People that speak to this; includes 15 Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action that bolster the cause; and concludes with 45 detailed recommendations on what action needs to be taken.

Most of what she calls for involves various government bodies, including cultural training for ICBC agents and others involved with motor vehicle administration, funding for driver training programs for women or youth fleeing domestic violence and adjustments to road test routes where residential schools once existed to minimize in-vehicle trauma.

“No one says, ‘I want to stay in poverty,’ or ‘I want to go hitchhike today to get groceries.’ This is a life of necessity and urgency that most people don’t understand,” Sager said. “And so, what started out as this commonsense way to get people to work became this disruption of systems."

Sager has seen myriad problems intertwined with the pursuit of driver’s licences for Indigenous people.

Some include not having access to adequate vision care, not having access to required safety equipment for child passengers, not having the necessary ID (including not being able to use government-issued Indian status cards), having to travel extremely long distances just to take a driver’s program or a test and not having access to qualified mechanics to keep vehicles in good shape (which can result in vehicles not being accepted for driving tests).

To make matters more difficult, once a learner’s licence is achieved there may be few other people in the community with a valid licence. The new driver might then have a hard time finding a co-pilot, which also affects their ability to graduate to the next licence level.

Sager, who grew up along the Highway of Tears, says that people could be made safer, at least in part, by some of the solutions she’s proposing.

She writes in her paper that when Lewis, the young Haida Gwaii woman, went missing last year, a number of men she was working with expressed sadness and disappointment around not being able to offer her a ride, or look for her when she went missing, because they couldn’t drive.

“Would Shaylanna’s outcome have been different had she had a driver’s licence and she could have just gotten in a car and drove? Would she have been safer?” Sager asked.

She believes she already knows the answer. It’s the reason she’s done the work she has for the past four years with her driving academy, and why she’s also working on a doctorate degree through Royal Roads University, examining a similar subject — the impacts of colonization on driver’s licensing for Indigenous people.

Sager says that COVID-19 opened up another wound around the difficulty obtaining licences, because so many First Nations communities don’t have hospitals or adequate medical care nearby and people can’t access those services unless they can drive.

Ridesharing has diminished during the pandemic, and with news that Greyhound is now shutting down bus service across Canada (after closing its routes in Western Canada in 2018), the situation in rural areas is even more dire.

Sager has also heard stories about evacuations during wildfires that almost didn’t happen because not everyone drove.

“From my perspective, one of the things that keeps me going is I believe this is fixable,” she said.

Sager acknowledges that ICBC has helped her run her programs in the past.

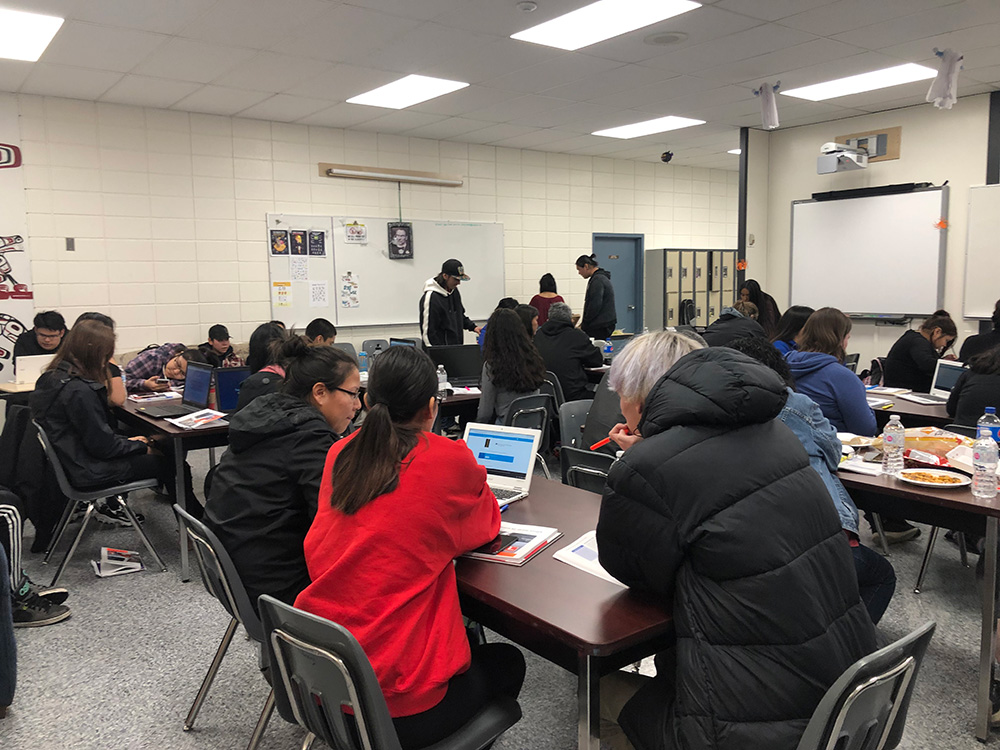

A few years ago, ICBC gave her a $6,000 grant to buy 10 laptops she could bring into communities to help people study for their licensing exams, and in early May it paid for her to go to Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation to host a two-week driver training session in Tofino. Participants from Ka:’yu:’k't'h'/Che:k:tles7et'h', Ahousaht, Tla-o-qui-aht, Huu-ay-aht and Ucluelet First Nations received some student courses for free.

In an email response to questions from The Tyee, ICBC said it has worked with Sager since 2018. As well as providing the grant, ICBC said it helped her deliver services in the Nisga’a Nation community in 2020 and gave her 300 “Learn to Drive Smart” workbooks over the past year.

ICBC says it’s acted on four of the top five barriers to driver’s licences for Indigenous peoples that Sager presented to them in 2019. These include:

- Changing the permission documents for minors to include tribal council members;

- Changing the learner’s knowledge test documents by replacing surname with last name to ensure the forms are completed correctly;

- Allowing students who travelled a long way to take the road test twice in one day if they fail the first time, rather than make them wait seven days between attempts; and

- Allowing vehicles with damaged windshields to be used for road tests as long as the driver can see clearly, because many Indigenous communities don’t have windshield repair services nearby.

ICBC says it’s also acquired equipment that will enable it to deliver services in remote areas starting in 2022.

But Sager argues more could be done. For example, communities currently need to apply for their own government funds to bring her in.

Sager and UBCIC have written a letter to several government bodies, including ICBC, the Ministry of Public Safety and the Solicitor General, the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction and the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training. They’ve asked for a meeting, as well as action on Sager’s report recommendations. They’re still waiting for a response.

Neskonlith Indian Band Chief Judy Wilson, the secretary-treasurer for UBCIC, agrees there are still too many hurdles for Indigenous people trying to get a driver’s licence.

“It’s still about the issues of access and still about the issues of poverty, and all of the multitude of issues that our people face on a daily basis — even trying to get basic needs met,” she said.

Wilson notes her own community has a fairly large land base, but to get to the places where you can harvest food and other materials, members have to drive. The reserves, she says, were not set up for people to be self-sufficient.

And Wilson says for many First Nations people, there is still trauma around motor vehicles, another major barrier Sager points to in her paper. This keeps people from even stepping into cars, let alone getting into one with the stranger who is the driving instructor.

“That happened to my dad.... They lived on a farm ranch, and my grandmother and grandfather were working on the ranch. My dad was like five years old. Him and his sister were playing down this little creek fishing, and then a truck came along. And the Indian Agent jumped out and grabbed them, and took them to the Kamloops Indian Residential School,” Wilson said.

“Their parents didn’t even know where they were. They had to ask around,” she added.

Wilson also remembers her own experience with child welfare. On one occasion, she was left in the care of an aunt who had a medical emergency. Child welfare came for her while the aunt was in the hospital. Wilson remembers seeing the vehicle pull up and being scared.

“We were always told not to get into strange vehicles,” she said.

As for Sager, she’s happy to keep doing the work she’s doing, but is hopeful government will make the work easier.

“I don’t think there’s anything in [my] recommendations that is really crazy. And I would hope that there would be some sense of urgency from the government to say, ‘We never looked at this before. These are great ideas.’ Not only is this going to support Indigenous people, it’s going to support British Columbia,” she said. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Transportation

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: