1. HIRED

In the fall of 2008, at the age of 48 years, Joan McArthur started upon an oilsands adventure. On the advice of friends, she applied for a job with the PTI Group, a subsidiary of Houston-based Oil States International. McArthur, who had just moved to Kelowna, B.C., knew little about the firm except that it was opening a new lodge called Wapasu Creek, which had been named after local Cree trappers, to accommodate some 500 workers from Suncor. Like everything in Fort McMurray during the oil boom days, PTI needed staff yesterday. After submitting her application McArthur got hired in two days.

Given her work experience as a bank teller and operator at a RCMP call centre, a PTI manager told McArthur that they were going put her to work immediately at the front desk. He then asked, “How soon can you get here?” McArthur now wishes she had asked, “What’s wrong with the place?”

PTI, which changed its name to Civeo and listed as a British Columbia corporation for tax reasons, describes itself as one of the world’s largest “integrated providers of workforce accommodations” for fossil fuel extractors in Australia, Canada and the United States. It builds temporary camps from scratch. Then it contracts them out on a fee-per-day basis that covers board, meals, laundry and other sundries for fly-in and fly-out workers. Sometimes the contracts cover several years and hundreds of millions of dollars. The arrangement allows natural resource companies to focus on putting people to work extracting fossil fuels instead of worrying about housing them.

The PTI Group started off with small modular rental housing for oil drilling crews in the 1970s but then graduated to Canadian oilsand camps in the 1990s. In 2007, PTI started construction on Wapasu Creek Lodge located near Suncor’s Firebag project and Imperial Oil’s proposed Kearl Lake mine.

The sprawling complex took only 257 days to assemble on 240 acres of cleared boreal forest thanks to its efficient Ikea-like construction. The temporary modules, painted white and blue, were stacked three floors high. At its peak the facility would eventually feed and house 7,000 workers a night, and become one of the largest and most storied work camps in the tarsands.

To get to Wapasu, McArthur hurriedly abandoned the tranquility of Kelowna and flew into the busy Fort McMurray airport. From there she boarded a bus for a two-hour long ride to camp. As a landscape of frozen trees and industrial mine sites passed by her window, she thought she “was going to the ends of the Earth.” Later on that day the single woman muttered to herself, “Oh my God, what I have done?”

Work at the front desk of the Wapasu Creek Lodge was like everything else in the oilsands: frantic. Every day hundreds of tired workers rushed through the front doors to the counter to register for their rooms. “It was a free-for-all. There was no decorum,” said McArthur. Workers without reservations often waited for hours to check-in. After a day or two, staff veterans told McArthur she was too bank-teller nice, and that she needed to toughen up. One of her trainers was Kathleen Karpan, a former Saskatoon secretary, who had arrived in camp in 2007.

Karpan also started cold at the front desk with limited training, which was the Fort McMurray way in those days. It was “a sink or swim” situation, and Karpan, a skilled organizer and fast typist, swam. Soon Karpan wasn’t just checking workers into their rooms but also dealing with medical emergencies, witnessing everything from heart attacks to seizures. Karpan took to that work and the friendships nurtured in a mining frontier. “You could tell who was there to work and who was there to party. You either spent your money on drugs and alcohol or you put it away.”

Everyone said the money in the oilsands was good but McArthur had no idea how good until she got her first pay cheque. “It was $2,300 for two weeks,” she said. Or double what she could have made at a bank in Kelowna. “Wow,” she thought. “I can put a lot of my savings away up here.” Her salary later enabled her to buy a home and car.

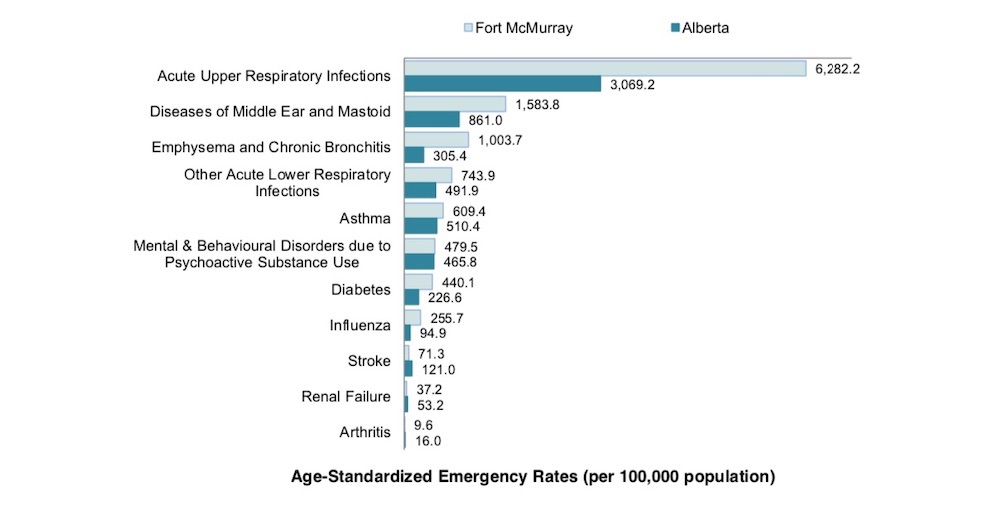

But a month later her symptoms started. She coughed and hacked her way through her 12-hour shifts at the front desk. Respiratory infections followed. Six months later she wasn’t feeling any better. In May of 2009 she was coughing so hard, she couldn’t sleep. She left camp and returned to Kelowna where her family doctor diagnosed her with pneumonia, adult onset asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. McArthur couldn’t believe it; she had never had any lung problems before.

After six months of rest and tests ordered by her doctor, McArthur debated about returning to Wapasu. “If I’ve got puffers, I should be okay. I couldn’t give away a $75,000 a year job just for asthma,” she reasoned. That decision changed her life.

By 2009, Karpan, then 32, had developed a chronic cough. It slowly turned into recurrent respiratory infections accompanied by skin rashes, laryngitis and other problems. The failing health of the two women plunged them into an ongoing struggle for safer work conditions with their employer, and then their union. A damning 104-page air quality report lies at the centre of their long struggle. McArthur, a blunt woman of Scottish ancestry, now describes her “holy crap” ordeal about workplace exposures to dust, mould and diesel fumes as “a nightmare gone bad.” Karpan compares it to an abusive relationship. “We didn’t realize how bad it was until we were out of it.”

2. THE JOB

When Karpan first arrived at Wapasu Creek Lodge, she compared it to the “eighth wonder of the world.” The Saskatchewan farm girl had never seen anything like it. In this remote outpost, PTI staffers from Canada, Europe and the Philippines swept the floors and changed beds in a complex of buildings that looked more like a penitentiary than a lodge. First Nations and Somali guards policed the place.

The level of comings and goings at the camp boggled the mind, said Karpan. Some days the camp would be overbooked by 200 people. “The left hand never knew what the right hand was doing.” As a result, the front desk turned into a three-ring circus with jangling phones and angry clients. One day a client keeled over with an apparent heart attack and hungry workers stepped over the man to line up to get trays for dinner as one of Karpan’s colleagues administered CPR. “It was insane. Every day was different. We definitely earned our money.”

As front desk workers, both McArthur and Karpan had a duty to report complaints and other irregularities to management. They did so diligently. Some of their emails documented the smell of diesel exhaust in the front desk, bed bugs, uncleaned laundry and bathrooms, bathrooms without toilet paper and muddy floors. In 2009, Karpan wrote to management, for example, about floor waxing. “I hate to complain but the smell of wax is VERY OVERPOWERING at the Front Desk, not to mention toxic, and makes us all nauseous and lightheaded.” Other front desk workers routinely reported air quality problems. In 2011, another worker told management that guests were complaining about “Air Quality in the camp…. Our lungs were not meant to be breathing this dust and dirt.”

A year and half into her job, Karpan developed a chronic cough. When working at the front desk, she had a runny nose, sore throat and often felt lightheaded. Her voice strangely changed into such a throaty rasp that people thought she smoked (she didn’t). At the time, the dust in the building was so bad it “looked like a desert/prairie dust storm in the building.” She remembers that waxing and chemical fumes were often so strong that guests walking down the halls would put their shirts over their mouths.

In the spring, a putrid and swampy smell filled the main lobby. The women later learned that water routinely pooled under the modules and that a sewage pipe had broken under the main building. It took six months for management to repair it.

Depending on the season, dust became a ubiquitous occupant. Every morning front desk workers could draw cartoon characters on the dusty screen of their computers. One of her co-workers, Paulette McNeil, recalled looking up at the skylight above the front desk on a regular basis to behold a shower of dust suspended in the sunlight. “It was amazing,” said McNeil. In the dining room, clients regularly complained that dust coated their salads. In some hallways, it was impossible to recognize the face of people coming down the hallway because of the haze.

Many staff suffered from coughs, sleeplessness, headaches, itchy skin and sore joints, said McNeil, who worked at the camp for a year. “But we didn’t look for something to blame,” she added. “We made excuses. ‘Oh, we are away from home. It is a new job. We are working 12 hours a day.’ And that’s why we are not sleeping and feeling well.” The company assured staff that it championed “Safety First.” Yet McNeil, who loved her job, remembered that clients as well as staff all reported a variety of baffling symptoms.

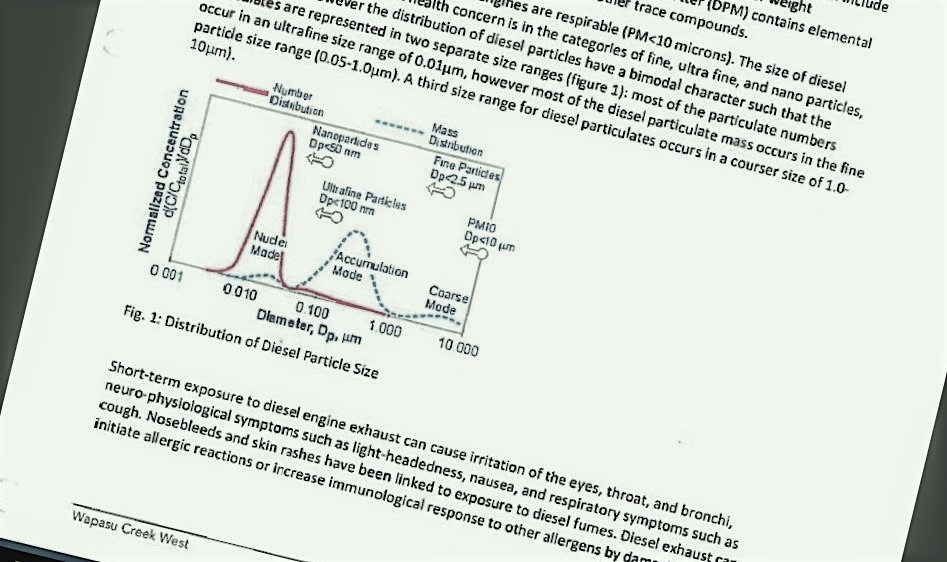

For many years the diesel fumes became a constant lament from the front desk. (Exposure to diesel pollution can cause cancers of the lungs and bladder, also a variety of respiratory ailments, allergies, headaches, dizziness, fatigue and nausea.) Every day scores of buses would marshal outside the lobby. In the winter, they let their engines run all night in the minus 40 weather. Front desk workers barraged management with memos about the stink.

3. WAPATRAZ

In 2010, one of Karpan’s colleagues again addressed an email to management on the issue of diesel fumes: “This really has to be dealt with ASAP… the lobby is full of exhaust and it is so hard to breathe.” Another worker wrote later that year, “I was kept awake most of the night coughing from the exhaust fumes… the smell was really strong in the bathroom as well as the hallway.” It took a year for management to move the buses to a different stationing area. Eventually, electrical outlets were installed so the buses could plug in during the winter, and keep idling to a minimum.

In 2010, PTI introduced some HEPA portable air filters in the lobby to deal with dust. But front desk workers moved them into the halls because of the noise. That year, PTI signed a three-year $462-million contract with Imperial Oil to provide modular housing units for its workers at the $8-billion Kearl Lake project which would eventually extract 300,000 barrels of bitumen a day. The lodge added an east wing, and then a separate west wing and then the Henday Lodge.

By 2013, Wapasu boasted that it was “the fifth largest hotel in the world.” With so many mouths to feed, PTI declared that it was the single largest buyer of yogurt in Canada. A U.S. hedge fund manager, who invested heavily in the company during the bitumen boom, described PTI’s camps as “the Club Med of remote exploration facilities.”

That’s not how workers described Wapasu Creek Lodge. One blogger, a B.C. doctor, wrote that “rows upon rows of barracks-like, three-story, prefab buildings, austere in the Arctic night, bring to mind prison camps of the Soviet Gulag.” Others just called the place Wapatraz. Some clients even started wearing baseball caps and hoodies with the logo Wapasu Correctional Facility. Another popular T-shirt showed a chain link fence with the camp’s austere architecture in the background and the word Wapatraz. Some former guests told The Tyee that they had slept at worse non-union camps in the oilsands. Given the scale of the operations, they described service at Wapasu as grossly institutional but functional.

To accommodate thousands of Kearl Lake construction workers, life at Wapasu became more regimented. Camp workers waited in line for check in, waited in lines for dinner, and waited each morning at a place called “the Brass Alley” for the lights to turn green — their cue to board buses for the hour-long drive to work.

Imperial Oil set the rules for camp, and mandated no alcohol. Guards at the gate enforced the rules and kept out random visitors and sex workers. Workers couldn’t even park a car on the grounds without a permit. One group of workers made fun of the conditions by posting an animated cartoon on YouTube in 2011. “It mocked the stupidity and pettiness,” said Karpan.

The cartoon depicted two executives in a boardroom debating how to make camp accommodation worse. “What are we going to do about the possibility of high morale?” asks one character. “We will put them in camps, take all their civil rights away and serve them the shittiest food we can find,” replies another. The satire was called the Kearl Lake Think Tank. It has received more than 200,000 views on YouTube since 2011.

Shortly after Wapasu’s East Lodge was completed in 2010, PTI management transferred Karpan and McArthur to jobs there. That’s where the two workers became friends and started to compare health notes. At the East Lodge the women said that they noticed better air flow and quality, but their symptoms didn’t completely clear. In 2011, Karpan fired off an email to the union: “Many are complaining of constant headaches, acid reflux, asthma, lung issues… which flare up here but ease up when at home. I sat with a gentleman on the plane recently who used to stay at Wapasu… he said the air quality sucked here and he was ALWAYS sick/stuffed up/couldn’t breathe.”

In 2012, Ronald O’Rielly, now 62, stayed at Wapasu while working as a millwright on the Kearl Lake project for one year. O’Rielly befriended the women at the front desk, including Karpan, and often brought them coffee. Some mornings he couldn’t believe the dust he’d encounter in the hallways. “It was just like you were walking through a fog and I’m from Newfoundland and know what fog is like.”

The dust came off workers’ boots and was so thick in the air some days that “you couldn’t see from one end of the corridor to another.” The oilsands workers living there left the lodge for the day or could take refuge in their rooms, said O’Rielly. But the front desk staff “were exposed to it all the time.”

4. FUGITIVE DUST

O’Rielly wasn’t the only worker that noticed the dust. In the spring of 2012, a Kearl Lake welder named Iron Pete devoted one of his popular blogs to dusty Wapasu. He attributed the heavy clouds of dust in the building partly to the winter practice of dumping limestone on the roads to reduce ice hazards. The dust then flowed into the building on boots and clothes. Early in the morning Iron Pete could see clearly down the halls. But that picture changed as soon as a parade of dusty workers emerged from their 110 sq. ft. rooms and trudged to breakfast. Dust hung heavily in the air, wrote Iron Pete. “It reduces visibility like a very dirty pair of glasses. You immediately wonder about the effect it will have on your lungs.”

Dust from mining and worksites has been disabling human lungs almost as long as human history. It is also a constant companion in the oilsands for obvious reasons. Bitumen is a mixture of heavy tar-like crude trapped in sand, clay and water. A typical bitumen deposit consists of 10 per cent tar-like crude, four per cent water, three per cent clay and 83 per cent silica sand.

The whole point of bitumen mining and upgrading is to separate the bitumen from the sand. As a result, clouds of “fugitive” dust fly off the open pit mines, unpaved roads, and pyramids of petroleum coke. Plumes of dust steadily mark the movement of trucks and buses while large clouds of dust often hover over the region’s massive lakes of tailing waste. Fugitive dust also accounts for the majority of particulate matter in the air.

One group of scientists described the composition of the local version of fugitive dust capable of floating in the air as a “mixture of native soil with deposited engine exhaust, brake and tire wear, stationary source emissions, plant detritus and other biological material, tailings sands, and mined or naturally occurring bitumen.” The dust can also attach to a variety of polycyclic aromatic compounds, many of which are carcinogenic.

A 2014 report on fugitive dust in the region noted: “Extended exposure to elevated levels of dust can cause adverse health effects, particularly if the dust contains crystalline silica, asbestos fibers, heavy metals, disease spores, and other toxins.” The study said it wasn’t unusual to find “excessive dust deposits… on surfaces inside residences near mining facilities, causing health concerns.”

For years, First Nations have steadily complained about layers of industrial dust falling on blueberries and other edible plants in the region. The dust is so thick, that it retards plant growth.

Many oilsand companies fully recognize the hazard of silica dust as a lung spoiler. Suncor, one of the oldest and most respected bitumen miners, has a well-established protocol for exposure to silica. Its protocol notes that “Crystalline silica dust particles that are small enough to be inhaled into the lungs can cause a number of health problems, including silicosis, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema, as well as a higher risk of contracting respiratory infections.” As a consequence, many of their workers take Air Purifying Respirator Training and take part in a Silica Health Assessment Program that includes regular lung X-rays.

But the women say whenever they asked PTI about the dust levels and air quality, the management said everything was okay. Occasional visits from Occupational Health and Safety also gave the camp a big thumbs up. At one point Karpan thought maybe she was just imagining things. But her cough persisted.

5. THE UNION

One of Alberta’s biggest unions, the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 401, represented Wapasu’s 700 staff workers. For a while, Karpan even served as a shop steward. Just before negotiating a new contract with PTI in 2014, the union commented on the camp’s work conditions. A memo by Tom Hesse, now UFCW Local 401 president, took issue with PTI’s new habit of describing its temporary housing units as “lodge accommodation” instead of a basic work camp.

Hesse wrote that PTI’s modular units in which his members worked and lived “can be problematic. Most time is spent indoors and these structures can ‘choke you.’ They are interconnected boxes with poor ventilation. They are at risk for mould…. Thousands of workers from multiple industrial sites bring dust, chemicals and all that is associated with the tarsands and its industrial and environmental trappings into temporary boxes where UFCW 401 members work and live. Throw a bad boss or an arrogant and disrespectful chef into the mix and the situation can become impossible.”

Few outsiders, added Hesse, appreciated the sacrifices union workers at the camps were making “to ensure that Alberta achieves its oil production goals. Most say the pay and benefits are so good that workers should simply ‘suck it up.’” Hesse said the only answer to that kind of thinking was “No.” Hesse later told The Tyee that he also encountered clouds of dust in the lodge and raised the issue of silica hazards with PTI.

Meanwhile PTI tried to address some complaints. It hired a Fort McMurray company, CMV, to pump mould out from underneath the trailers. The workers told Karpan’s colleagues it was some of the worst they had ever seen. They found spaghetti and grease mixed with the mould because sewer pipes weren’t properly connected. The men wore hazmat suits and respirators for the dirty job.

In 2013, the company also introduced a “Boots Off Policy” with the goal of reducing dust levels in the lobby and halls. Front desk workers, including Karpan and McArthur, were told to post signs asking guests to remove their boots “to reduce the silicate dust and particulates in the air we all breathe within the buildings,” as well as “eliminate the potential for petrochemicals being tracked on the Wapasu footprint.” The company made booties available for the workers. But when guests continued to complain about coughs and lung ailments, said Karpan, the management revised the signage five months later. The new signs asked guests to “reduce the mud within the building.”

That year, another front desk worker quit the chaos at the booming camp. In a farewell letter, the then 23-year-old woman explained why she couldn’t stand working at the front desk anymore, calling it “the most exhausting and torturous position I’ve ever been in.” She added that “if there were ways where employees can voice their opinions and proper measures were taken to ensure necessary change was happening, I most definitely could have stayed. But NO! We have no voice at Wapasu, we have no feelings and we ARE NOT HUMAN. We do as we say, we take abuse as it’s given and if we have a problem, then pack your bags…. And why would someone want to work for a business that carries itself that way? Well of course, the money.”

When the union asked the worker why she quit, she gave them a list. It included computers that didn’t work properly, mould at the front desk, chaotic scheduling and a sloppy attitude towards cleaning up biohazards such as a box of spilled needles by diabetic clients. “When clients are angry and yelling at us and demand to see the management, management is nowhere to be found,” she told the union. The 30-year-old woman now attends law school and said that she could still remember Karpan’s cough.

Over time, Karpan and McArthur slowly learned that indoor air quality remains a delicate science complicated by building design, air velocity, humidity and temperature. In Canada, there are really no federal standards or regulations governing indoor air quality for workers. In 2019, the Office of Risk Management at the University of Ottawa completed a review of the subject for professors and students cooped up in “office-type environments.” It emphasized that there are no federal standards for exposure to volatile organic compounds let alone airborne mould. “Complicating matters are the manner in which various substances and matters can interact with each other and the individual nuances and susceptibilities that every person has.”

In 2014, McArthur reported off work three times with pneumonia and lung infections. That year, the company had laid off many janitors, claiming lower occupancy reduced the need. McArthur noticed that “the dust was crazy.” As they had done for years, the women continued their campaign to improve conditions in their workplace. In March, Karpan fired off an email to management about dust and mould. “Once again we are hearing complaints about the dust in the entire building, the lack of overall cleanliness and the mould/sewer smell in Wing 28.”

In April 2014, McArthur penned a missive about filthy halls: “This is unsafe working conditions and have caused me personally to be off sick with two lung infections and pneumonia these past few months…. I am very passionate about the dust and unsanitary conditions in our lodge.”

6. FINDINGS

In 2014, the union finally hired a Canmore company called Indoor Air Quality Management led by Karen Rollins to do a full air quality assessment of Wapasu. Rollins’ group visited the facility twice and interviewed staff and management. It also spent three days in March of 2015 testing air quality in Wapasu West, one of the most recently built facilities. In talks with PTI, the union agreed that they wouldn’t circulate any test results till PTI/Civeo had presented its response and action plan.

Prior to that visit Rollins passed out a health survey at seven Civeo lodges including Wapasu West, Wapasu East, Wapasu Main and Henday. Nearly 100 union workers responded. Karpan said many workers were too concerned about their pay cheques to raise any problems. Still, based on the number of complaints and symptoms reported by staff “and because most people felt better when not at work and worse as the work week progressed, we can conclude that there is an indoor environmental quality issue at the Lodges,” concluded the report (whose four parts you can read here, here, here and here). The survey indicated that there was more than one indoor contaminant-related issue, including airborne particulates, diesel, fungi and VOCs.

McArthur and Karpan did not see the results of this health survey until years later.

Nor did they see Rollins’ 104-page air quality report for another two years. It confirmed the workplace conditions McArthur and Karpan had been complaining about for years with a thoroughness the union had probably not anticipated. It detailed the presence of mould, building code violations, mechanical system deficiencies, noise issues and substantial evidence of water intrusion under the modular buildings due to poor drainage.

“There are many lessons to be learned from this report regarding the design and management of prefabricated structures destined for remote sites,” said the report. It also identified problems “inherent in the building envelope, architectural detailing and mechanical equipment. We hope that the next generation of prefabricated structures will be improved.”

PTI/Civeo, however, had not made the inspection an easy process according to the report. As Rollins notes in its pages, lodge management placed a series of limitations on her investigation. They refused to share architectural and mechanical drawings along with maintenance records or even allow access to knowledgeable maintenance workers. Management also didn’t permit Rollins and her team to take air samples under crawlspaces or allow them access to guest sleeping quarters. Nor could Rollins’ team enter older buildings in the complex to take comparative air samples. Free access to buildings and personnel is generally considered essential for a proper air quality investigation.

Despite Civeo’s restrictions, the report catalogued a laundry of list of problems. Rollins’ team, for example, found toxigenic fungi in ceiling areas subject to repeated roof leaks as well as fungi in a crawl space under the kitchen, the lobby room and furnace room of the women’s gym. Rollins described the kitchen crawl space as “one of the worst areas” her team had ever tested for fungi. The report noted that this kind of fungi infestation could easily migrate up into occupied spaces.

The report documented other contributors to poor air quality. Airborne particle counts were higher inside some buildings of Wapasu West than outside. In some cases three to seven times higher. Her team found levels of carbon disulfide, a fungicide, 40 times higher than guidelines in the housekeeping area. (The fungicide can cause nausea, vomiting, dizziness and headaches. In high concentrations it can damage the kidney and liver.) The report also confirmed that many of the health symptoms reported by staff over the years “are strongly correlated with health effects from diesel, vehicle exhaust and fungi.”

In addition, Rollins also documented a dozen building code violations including the migration of surface water under buildings. One crawl space contained two inches of standing water. Others contained mouldy debris. She found that metal warping between the prefabricated units had ruptured the roof membrane and metal siding making the units vulnerable to air and water leaks. Despite the installation of a new roofing membrane at Wapasu West, Rollins found recent staining of ceiling tiles. Most had dried, but several were still moist. Dripping water in the main corridor required a bucket and caution sign. And on it went.

Civeo appeared to have an Indoor Air Quality Management plan but Rollins didn’t find evidence that it was followed or enforced. “We did not see any completed mechanical equipment checklists, maintenance inspection forms, examples of complaint response forms or evidence that the plan is reviewed.”

The report devoted several paragraphs to the dust issue. The camp’s boots off policy was reported to be only 40 per cent effective. The lodge did not allow Rollins to examine and check the HEPA portable air filters installed in 2010. “The actual content of the dust is unknown. It may contain silica which is a health hazard… some respirable dust particles can also serve as vectors for other contaminants.” The report recommended extensive dust sampling during the summer dry months.

Rollins concluded by noting that Civeo’s existing indoor air quality management plan needed serious improvement: “There is little evidence that health complaints by workers are taken seriously.” The company’s refusal to share building plans or even allow Rollins to interview maintenance people contradicted Civeo’s professed “commitment to indoor quality,” said the report.

Furthermore, Rollins wrote that the presence of carbon disulfide “suggests to us that Civeo may have attempted to minimize micro-organism levels prior to our visit in order to skew our test results.” She recommended that a building envelope specialist identify roof leaks and repair work and that mechanical equipment be upgraded with an effective filtration system to filter out flies and visible dust.

Rollins’ report also took apart a previous air quality report by Western Health and Safety. PTI staff collected all the samples and submitted them to the Calgary firm for analysis. The report found no mould or air quality problems. Civeo even sent the report to Karpan’s doctors in 2013. Rollins criticized the WHS investigation for using faulty sampling methods for mould and volatile organic compounds. It also tested for large airborne particulates instead of tinier particles two and half microns in size, far deadlier to the lungs.

Contrary to what WHS stated in its report, Rollins found that data on carbon dioxide levels greatly exceeded safety limits at Wapasu Main front desk where the women used to work and at Wapasu East front desk where the women then worked.

Rollins also underscored a critical issue for staff working at the camps. Occupational exposure guidelines for contaminants as varied as dust and diesel fumes are largely designed for people who work an eight-hour shift five days a week. “Workers at Wapasu Creek West work 10-hour days for 20 days in a row.”

PTI/Civeo responded to the report with a three-page memo entitled “Indoor Air Quality Assessment and Corrective Actions.” The company said it would continue to enforce a “no idling” policy for the buses and enforce its boots off policy. Drainage under the wet and mouldy kitchen in the West Lodge had been improved with pumps “as a pilot project.” New filters had been installed to reduce dust levels. As for questions raised about building design, Civeo said the complex “was designed and built to the standards and code requirements at the time of construction.” The company insisted that carbon disulfide “is not found in any product used by Civeo.”

Almost three months after the Rollins report, PTI/Civeo also commissioned an air quality report by an Edmonton company, Clarke Consultants. It found no evidence of diesel exhaust in the lodges and declared the “indoor mould reservoir” in the East Lodge kitchen had been eliminated. It also reported levels of respirable dust and silica were below occupational exposure limits because “the lodges were operating at less than half of capacity” which meant less foot traffic. Some activities indoors, however could still result in dangerous exposures. Anyone directing buses outside near the Brass Alley, for example, were “at a greater risk of overexposure to silica.”

The women didn’t see that report until they later put in a grievance to the Alberta Labour Relations Board. Meanwhile, the women worked away at the lodge and waited for the release of the Rollins report in 2015, but nothing appeared.

7. FIRED

Karpan’s health issues became more than a sharp nasty cough, and degenerated into pneumonia. In 2015, she experienced four bouts of bronchitis, one of laryngitis and a tonsil infection. After returning to Wapasu from a holiday on Dec. 19, she discovered that the East Lodge had been closed. That was the place her environmental sensitivities acted up the least. She had a doctor’s note to be accommodated there for shift work. But management assigned Karpan to Wapasu Main Lodge where she says she developed bronchitis and laryngitis within 24 hours of returning.

When management refused to move her to West Lodge, Karpan decided to exercise her right to refuse unsafe work. Dressed for work and clocked in, she returned to her room waiting for a call from management or her union. None came. When her coughing got worse the next day, she called in sick and went to the Fort McMurray hospital.

McArthur joined her. She, too, had been asked to work at Main Lodge that month. Against her better instincts and her doctor’s notes, she decided to give it a go. Over several days she developed bronchitis, and felt she couldn’t breathe. A physician at the hospital saw the women separately. They both got the same prescription: Go home and see your family doctors.

After handing in their doctor’s notes to management, McArthur and Karpan left Wapasu and flew home. Their doctors put them on medical leaves.

In Saskatoon, Karpan spent 18 months bedridden. She was so sick some days her sister had to put on her socks. (Her sister still helps tie her shoes.) In early 2016, one of her doctors told Karpan she had a choice to make: “If you go back to that work environment, you are risking getting permanently sick, a potential permanent disability, or even worse; the possibility of coming out in a body bag.”

In January, union president Doug O’Halloran called McArthur and offered her accommodation by changing her worksite to Wapasu West. McArthur said she wasn’t interested, and was exercising her right to refuse unsafe work. “We are hoping you will help us.” Two months later O’Halloran wrote to Mike Pisak, Civeo’s director of human resources about the “very concerning and disturbing issues” raised by McArthur and Karpan at Wapasu. “Their health conditions have started and or magnified over the years with little or no concern showed by their employer, PTI/Civeo.” O’Halloran ended the letter by suggesting it would be reasonable “to find a solution that addresses their concerns and compensate them for years of inaction by PTI/Civeo.”

According to the women, O’Halloran asked them what would be fair compensation. The women brainstormed and suggested a million dollars each given their medical symptoms and loss of income and benefits. Civeo countered with $60,000 as severance payment. O’Halloran wrote back a year later saying that $60,000 was “nowhere in the ballpark.” He suggested that Civeo “counter offer substantially.” The company never did.

In July of 2016, PTI/ Civeo fired McArthur for job abandonment while on medical leave.

Tom Hesse, then the union’s executive director of labour relations, informed the women in September of 2016 where things stood. The women expected compensation for their health issues and working in an unsafe environment yet PTI/Civeo had offered a typical severance package based on years employed. The women had rejected that approach. Hesse advised the women that union counsel had told him, “General damages for workplace illness or injury including in respect to provide a safe and healthy workplace are not available to the workers either through a civil trial or the grievance process.” He advised the women to pursue the necessary appeals before the Workers’ Compensation Board.

In May of 2017, the company fired Karpan on the grounds that she had not provided enough medical information to support her absence.

8. THE REVEAL

A fellow co-worker, Norm Soucy, who worked as a professional electrician at the camp, says in his opinion the company fired the women because they made too much trouble. “They laid them off instead of dealing with the problem. When you lay off the problem makers, the problem goes away and the rest won’t speak up.”

Soucy, who has worked off and on in Fort Mac since 1978, was employed at Wapasu for four years. He recently retired. The plain-talking 70-year-old confirmed that there was so much dust everywhere that it even clogged the smoke detectors. “Since leaving I haven’t had a problem with coughing or congestion.”

Soucy said there was so much water and mould under the trailers he never went down there to replace electrical cables without donning a Tyvek suit and mask. Before the company installed electric heaters for the buses they idled all night long outside of the lodge. “All you could smell was diesel at the front desk.”

The portable air ventilators installed by the company “were too small for the job” and “all they did was blow the dust around.” He suspects that the women got sick because they worked indoors 24/7. “They were at the epicentre. They couldn’t get away from it. And they weren’t the only ones suffering.” In contrast, electricians and maintenance workers spent most of their days outside the buildings. Whenever Soucy entered a lodge, he could feel his eyes start to water.

He said the money was good at Wapasu but the hours were just unbelievable. He added that the company never took a proactive approach to conditions at the lodge. Nor did government regulators. It seemed to fit a pattern in the oilsands. When a fellow worker got electrocuted at Civeo’s nearby Beaver River Executive Lodge, it took Alberta Occupational Health and Safety two years to file a report. “There was no complaint department that went anywhere but the back door. It was run like a zoo.”

Meanwhile, Karpan’s doctors kept on asking her for a copy of the air quality report paid for by the union. The doctors told her that such information would help with a proper diagnosis. When she politely asked the union for a copy in 2016, her union rep said it wasn’t ready. She asked three more times that year and got no response. In early 2017, she tried again.

Three months later, Clayton Herriot, the union’s senior labour relations officer, finally replied with a copy of the Rollins report. “While we have no legal obligation to provide this to you, we have chosen to do so, in the interest of transparency,” wrote Herriot. He explained, “The reason I am pointing this out is in response to the increasingly antagonistic tone of your correspondence.”

Herriot emphasized that the union was on the side of the workers. “Unfortunately air quality is not a static matter. The report is qualified and relates to a particular period of time.” He thought the company had been “somewhat responsive” and instructed Karpan to only use the reports “for the purpose of understanding your medical condition.”

The Rollins report was almost two years old when Karpan and McArthur separately read it. As they pored over its pages, they were dumbfounded. “I knew things were bad but I didn’t know how bad. It really shocked me,” said Karpan. McArthur said the contents of the report actually stunned her. Both believed the report validated everything they had documented over the years. It also explained their never-ending symptoms. The women no longer felt they might be crazy or that their symptoms were in their heads.

But the women couldn’t understand why the union withheld the report from them for so long. They felt betrayed. Moreover, the report could have aided their doctors and given the women an opportunity to better protect themselves against occupational exposures. “If the union or the company had offered us PPE, or a safe work environment, none of this would have been an issue,” said Karpan.

Karpan asked the union why it had not disclosed the contents of the Rollins report to its membership. She didn’t think it was to right to withhold such information. In a lengthy email, Clayton Herriot replied that sharing it wasn’t necessary. “To simply blanket our membership with this report would be foolish. It has scientific components and for it to have meaning it needs to be put into context. There was no need to cause panic over the matter.”

Herriot explained that there appears to be “no scientific consensus on the issue…. I am not a doctor or a scientist but I know that respiratory problems are very personal and relate to an individual, their unique make up and sometimes their response to the environment. We have many many members also that have not expressed a concern whatsoever about the air quality.” He asked Karpan for a face-to-face meeting “to build trust and work towards a fair and sensible resolution of your issues.” But by then Karpan had no more faith in her union. Relations deteriorated from there.

9. PROTEST

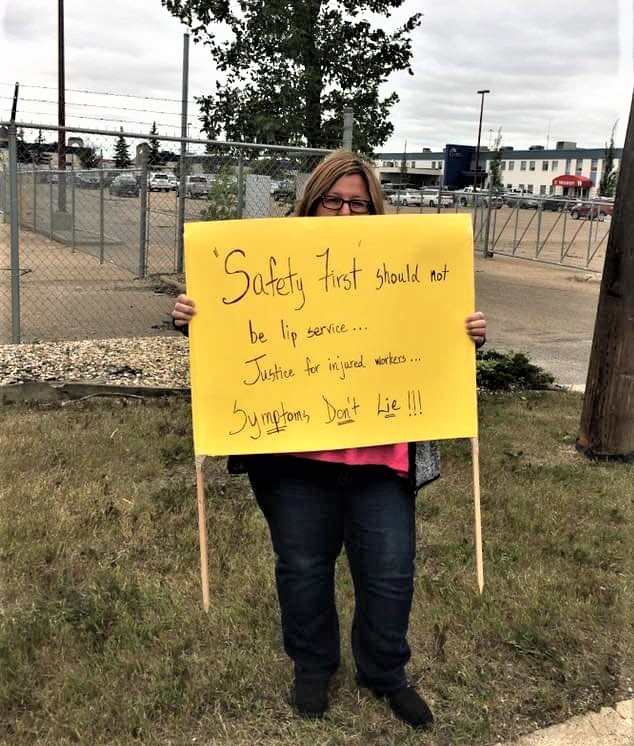

Feeling powerless after being fired while on medical leave, the two women decided to stage a protest. They felt they had a duty to talk about the air quality report even if it only changed the life of one other worker. With their doctors’ permission they flew to Edmonton in July of 2017 and marched outside the entrance to Civeo’s headquarters with a few friends. One held a sign that said, “‘Safety First’ should not be lip service. Justice for injured workers. Symptoms don’t lie.” No one came out to talk to the women.

After the protest and the posting of videos, the women received a letter from Kenneth Fitz, a lawyer representing Civeo warning them about defamation. “If you wish to commence a lawsuit, you should do so. If you wish to file a WCB claim, you should do so. If you wish to commence a human rights complaint, you should do so,” said Civeo’s counsel. But what the women should not do, added the lawyer is “publicly defame our client without apparent regard for the laws concerning defamation.”

The Tyee sent a number of questions to Civeo related to Wapasu Creek Lodge and its dealings with McArthur and Karpan. The company sent this response: “Given the privacy considerations involved, it would be inappropriate for us provide comment, other than to say that we believe this case was dealt with fairly and through proper regulatory channels.”

In January 2018, union president Doug O’Halloran wrote a final letter to the women. He advised them no settlement with the company would be forthcoming. As a result, the union “has advanced your matter to arbitration.” McArthur dashed off an impassioned letter: “Do you think just because Civeo says it’s over it is? I know this for sure, if I poisoned someone, I’d be in jail!!!! If I poisoned someone and didn’t tell them, do you think the outcome would be favorable to me?” O’Halloran didn’t answer. He died the next year.

When the union hired a lawyer to prepare an arbitration case for wrongful dismissal, the women told her that there were at least 70 employees with symptoms or diseases similar to their own working at the lodge. The lawyer emphasized that building their case would take a lot more time, money and medical examinations and documentation.

Correspondence between the union and the women from 2017 to 2018 shows an erosion of trust and a flood of frustration on both sides. In 2017, the union adjourned its arbitration for McArthur. On Sept. 14, 2018, both women were informed in an email that the union wouldn’t be taking their case to arbitration due to lack of co-operation and failure to produce sufficient information.

Unemployed, with no union representation and crippled by reduced lung capacity, the women debated their next move. Albertan lawyers frankly told the women that the case had too many political implications in a province so dependent on oil corporations. The province’s media didn’t reply to any of their queries. Finally, one lawyer they briefly consulted suggested they try the Alberta Labour Relations Board. The board heard complaints from employees when they felt their union hadn’t fairly represented them.

In December 2018, McArthur and Karpan submitted a lengthy complaint about UFCW to the board. In half a dozen thick binders full of carefully labeled documents and emails, they argued that the UFCW had failed in its duty to fairly represent their interests under their collective agreement. In particular they focused on the union’s failure to disclose pertinent health and safety risks by withholding the Rollins report for nearly two years. They asked the board to consider their plea and resolve “this ongoing fiasco by way of arbitration or any other means available.”

Shortly afterwards the women learned of the death of co-worker Steven Neville, a Wapasu housekeeping supervisor. At 46 years of age, Neville had died at the lodge after reportedly complaining that his lungs hurt. Neville, a large man, had notified friends on Facebook in 2017 that he had been diagnosed with sarcoidosis. He had spent 16 months on medical leave without being fired. Sarcoidosis has many different causes, but significant exposure to airborne crystalline silica or solvents is one of them. The incidence of the disease has been steadily rising in Alberta since 2005, and nobody knows why (see sidebar).

Neville, who came from Carbonear, Newfoundland, had worked for PTI for more than a decade. He also spent a lot of time in the part of the building where the Rollins’ air quality report had identified levels of carbon disulphide 40 times above the legal limit.

While reviewing her WCB file, McArthur found some interesting 2019 emails that pertained to Karpan. The emails were from Boris Makale who was hired by Civeo as a WCB specialist. Makale had in fact previously worked for the WCB. To assist in the investigation of a new claim submitted by Karpan, Makale wanted the WCB to consult air quality reports paid for by Civeo. “We would like these AQ reports to be used and not just the rather subjective AQ report [the Rollins report] that was commissioned by the union.”

In another email, Makale told the WCB that “it should be noted that these two are friends so not surprising that this should start up again.” Karpan read the emails in disbelief. How could Makale describe an independent third-party report done for the union as “subjective” while suggesting that reports paid for by the company were more objective?

On June 23, 2020, the Alberta Labour Relations Board issued a dense 18-page ruling. A panel of three board members reviewed the voluminous documentation submitted by the women and the union and dismissed their complaints against UFCW as “without merit” and as being “untimely.”

The board had little to say about the Rollins report and occupational health conditions in the work camp. “The air quality reports, in particular, were a key focus of the complaint,” noted the board. But debates about air quality didn’t really concern the board that focused its legal attention on rights conferred by the collective bargaining agreement.

The board noted that the union’s refusal to pursue a civil claim or grievance seeking damages for workplace-related illness was based on a sound interpretation of the law. The Workers’ Compensation Board was the sole venue for dealing with compensation from workplace injuries. As to the complainant’s claim that the union took a long time to process their grievance, the board noted that “a union need not process a grievance within the timelines demanded by a grievor.”

Tom Hesse, president of UFCW 401, told The Tyee that the union tried to do its best for the women. “We did care and put in a lot of resources. There was some tipping point. They were so angry at the world that we’d say black and they would say white.” He adds that he’s not blaming them for being so angry.

Hesse thought the report was shared with others at the time and can’t explain why the women didn’t receive a copy for two years. He said that Civeo strongly contested the validity of the report and did threaten the union with a lawsuit over it. “We were cautious about distributing the report broadly because of that dispute.”

He doesn’t know if the Rollins report was ever submitted to Alberta Occupational Health and Safety. He noted that the province’s OHS legislation does not recognize a place for unions. “The omission of a formal role and standing for unions in provincial OHS and public health regulation,” he told The Tyee, “makes it challenging for UFCW to assert its members’ interests and pursue remediation of health and environmental concerns.”

“Is there a legitimate concern about the conditions in those camps?” asked Hesse. “Yes.” He applauded the women for standing up for public health, and wished more members would do that. “We have no ill will toward these individuals. We advocated for them. We worked hard. They turned on us, and wouldn’t work with us.”

10. ‘A BETTER LIFE’

Kathleen Karpan lives in Saskatoon where she visits two respirologists, one rheumatologist, an eye specialist, an occupational doctor and a family doctor on a regular basis. Every day is a struggle but she now works part-time as an administrative assistant. Her doctors have diagnosed her with asthma and scleroderma, an autoimmune disease that affects connective tissues. Scleroderma is considered an occupational disease in the United States and can be caused by silica dust exposure.

When Karpan asked her rheumatologist if her condition could be due to workplace exposures at Wapasu, the doctor wrote the following on her medical assessment plan: “While l cannot say for certain that her scleroderma has resulted from a work exposure the fact remains that she does have new onset of autoimmune disease following an exposure at work. We do feel that autoimmune disease results from a genetic predisposition followed by an environmental trigger. I think it is entirely possible that Kathleen’s scleroderma was triggered by a workplace exposure.”

The medical literature is clear that silica and solvent exposure can cause several autoimmune diseases including scleroderma. It also says the inhalation of vapours, gas, dust or fumes in the workplace accounts for more than 10 per cent of all cases of asthma, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumonia, sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. According to the American Thoracic Society, “Strategies are needed to improve the recognition and prevention of the substantial occupational burden of non-malignant respiratory diseases."

Karpan recently applied for compensation to Alberta’s Workers’ Compensation Board. She was denied for the third time. The WCB says Karpan’s scleroderma is “pre-existing.” (She wasn’t diagnosed until December 2016.) She says that she never really wanted to rock the boat. “It was our job to report complaints. All we asked was that they clean things up. I was there to work hard, make money and have a better life.”

She worries that scores of other workers might be at risk for baffling autoimmune symptoms. She doesn’t want anyone to repeat her ordeal. “It's ironic that everyone we share our experience with are absolutely appalled, but not the people and agencies who are supposedly there to protect us and have the power to enforce the laws in place.”

McArthur lives in Kelowna on a disability income.

After being denied three separate claims for respiratory illness in 2009, 2013 and 2015, the WCB finally recognized her asthma and reduced lung function in 2019. She is being monitored for silicosis and goes for a lung scan every six months. She has been referred to a rheumatologist for connective joint problems. She lives with pain, fatigue, shortness of breath and tingling in her hands and feet. She calls the whole ordeal the “biggest battle” she has ever experienced in her life.

In 2009, the same year she was diagnosed with COPD and adult onset asthma, a group of Alberta researchers reported in a medical journal that occupational asthma was underreported and that “the numbers of cases presenting for compensation may be far lower than the true incidence.”

McArthur’s resolute convictions are expressed in one of her submissions to the Alberta Labour Relations Board. “We are not disgruntled, we are NOT too emotional, we are not antagonistic, we are not uncooperative etc. We ARE two women who got sick from workplace exposures and who were harassed, discriminated, retaliated against and fired while on medical leaves for reporting it.”

To this day, she does not feel her voice has been heard.

With the sustained downturn in oil prices Wapasu Creek Lodge is no longer bustling. In security filings, Civeo has warned investors that the company’s financial fate hinges on a swing in oil prices. As long as they remain low, its oilsands camps won’t be generating as much revenue.

Early this year, management installed plexiglass at the front desk in response to the coronavirus outbreak — something McArthur had asked management to do years ago for dust protection. Due to reduced occupancy the company frequently closes the east wing.

On the internet, clients still leave unflattering comments about their Wapasu experience: “Food is tasteless most times. Camp is dirty and sheets are hardly changed,” said one. Another posted: “Poorly maintained camp that is showing its age.”

In 2020, one worker wrote on Facebook, “They call it Wapitraz for a reason. The only good thing is free pool, and cash when you get parole.”

Karpan and McArthur, imprisoned by their illnesses, said they don’t yet feel they have been granted parole. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Health, Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: