[Editor's note: In this Tyee Solutions Society series, Chris Wood profiles what death row looks like for endangered species and their landscapes in three Canadian provinces.]

The darkness is slow to arrive in the southern British Columbia interior in June. For the community sheltering beneath the overhanging branches of a black cottonwood, the nocturnal working day -- the time for foraging in the relative security of darkness -- will be short.

A small blunt head, dark brown skin glistening moistly in the faint light, emerges from beneath a fallen log. The elongated torso and fat tail that follow it are blotchily striped in a lighter, yellowish shade. A lizard-like body, the length of a man's hand, rushes forward on short legs, the wide mouth snaps quickly, and the western tiger salamander settles in for a meal of beetle.

Not far away, a shape you could mistake for a length of milk-chocolate-brown rubber hose slips silently between the stalks of a dogwood clump. The motion stops. Then with astonishing speed the snake lashes forward and wraps itself around an unwary mouse, tightening its coils until the warm mammal ceases its struggle.

From a hollow in the oldest cottonwood, an owl with feathers patterned like weathered bark gazes through yellow eyes before taking silent flight.

For this Screech Owl, the brown Rubber Boa and prehistoric-looking Tiger Salamander, death row is a thin ribbon of green along Mission Creek, in Kelowna, B.C., shared during the day with bikers and hikers using its manicured recreation paths.

But the riparian ribbon of urban green space is only one of the ecological communities making a last stand in the Okanagan Valley. Along with Ontario's vanished Carolinian forest, Alberta's shattered foothills boreal mosaic and the Garry Oak meadows of the southern Gulf Islands, it is one of Canada's four most severely endangered landscapes -- and the most ecologically diverse. Ecologists here have identified five types of grassland alone.

Before the settlers

The reason is the Okanagan's unique geography. The long narrow valley, running north-south, has very different conditions at the top from the bottom.

The southern end of the Okanagan, around the town of Osoyoos, is a unique Canadian extension of a semi-desert ecosystem that widens out to the south into the Great Basin -- a vast region reaching all the way into the Sonoran Desert of northwest Mexico. It's the only place in Canada you can find true desert cacti growing wild.

Before European settlers came, the broad, flat benches of glacial sediment that sit above the valley's bottom lands were occupied by meadows among open Ponderosa Pine woods clumped with Saskatoon Berry bushes; the slopes rising to the plateaus above them were open sage deserts, described in a Ministry of Environment profile as "dominated by bunch-grasses, the wind, and the scraggly dark branches of antelope-brush."

Each of these provided homes to its own community of species. Amid the dogwood and rose brambles in the valley bottom, the musical Yellow-breasted Chats. Where old trees stood amid grasslands on the benches, Lewis's woodpeckers with cherry-soda coloured breasts, and the delightfully named Flammulated Owl. In the sagebrush uplands, Burrowing Owls and the Badgers that dined on them.

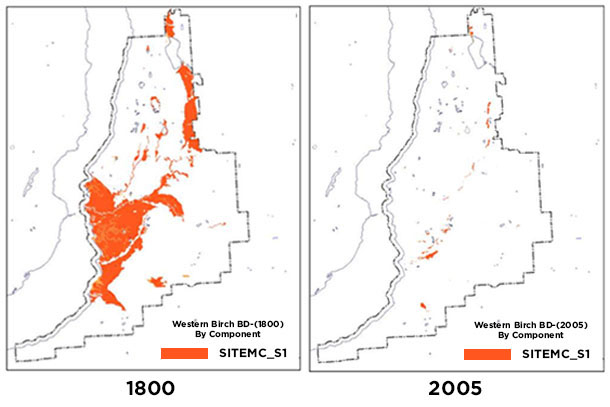

Perhaps the richest of the valley's many micro-biomes was a place where several creeks enter the east side of what is now Okanagan Lake. Their looping ox-bow channels braided through a semi-wetland of tall cottonwood, scrubby red-osier dogwood, water birch, and moisture-loving seasonal plants like the striking Giant Helleborine, a copper-veined orchid whose stalks can stand nearly waist-high. It was home to Rubber Boas -- Canada's only constrictor -- and Tiger Salamanders, our largest caudata, a branch of amphibians.

All but a few scraps of the former wetland, an estimated 96 per cent, have disappeared in the last century under the city of Kelowna. Remaining bits like the one where our endangered tiger salamander is (we hope) still enjoying a beetle dinner, are separated by hundreds of metres of concrete, pavement and human backyards.

Once a rich wetland

For most of the creatures that once occupied the rest of the Okanagan Valley's diverse terrestrial ecosystems, supportive habitat has been reduced by more than three-quarters in most places and in many to less than one-tenth of its extent when European settlement began here in 1859.

"All the footprint of Kelowna was basically wetland," observes Don Gayton, a retired Ministry of Forests extension agent and expert on the Okanagan's natural history. But "we like the same habitat [as wildlife], and so we drained the marshes to build our subdivisions." Orchards and golf courses replaced more of the appealing valley's natural ecosystems.

As more homes and businesses appeared, governments spent millions of dollars to suppress the region's natural cycle of frequent small forest and brush fires -- disrupting species adapted to those cycles and courting catastrophic blazes when years of accumulated fuel finally ignite.

"It's brutal," is how Tim Ennis, an endangered species and ecosystems specialist with the Nature Conservancy of Canada, describes the impact of development on the Okanagan's original wildlife. The region, often compared to California's Napa, continues to attract additional settlers.

"Species loss lags behind habitat loss," Ennis says. And with more of the Okanagan's un-protected landscape being developed, he notes, "There's a high degree of correlation between endangered ecosystems and private land."

Neither Ennis nor Gayton are quite ready to give up on the Okanagan's survivors. "We haven't lost all the parts of the engine," Ennis says. Recovery might be possible for some of the valley's death row inmates.

One bright spot is a movement to have several semi-protected parcels of land west of Osoyoos and reaching over Mount Kruger to the Similkameen River -- where some of the healthiest riparian birch, dogwood and cottonwood stands persist -- declared a National Park. Such a declaration would complete a national commitment to protect representative samples of every significant Canadian ecosystem.

Outside the proposed park, says Gayton, "we chip away and we get back one half of a per cent." But when "those tiny little projects" find a foothold, when water is restored to a single former oxbow in a stream, "the response is almost instant."

An encouraging recovery has been seen in the region's most iconic non-terrestrial species: sockeye salmon. After a decade of work restoring habitat, an alliance of Okanagan First Nations and other agencies recorded a strong returning run of sockeye in 2014, only to see numbers fall far short of hopes again in 2015.

For the nocturnal community along Mission Creek, every day -- and night -- will remain a fight to survive in the few and fragmented spaces not (yet) claimed for the Okanagan's vaunted quality of human lifestyle. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: