Related Document

High atop Burnaby Mountain stands a housing solution that could unlock one of the thorniest problems facing Vancouver and other expensive B.C. cities: Where to house the students, artists and other working singles who are critical to creating an information-based economy.

The City of Burnaby may be the first municipality in the world to legalize secondary suites within apartments -- also called lock-off suites -- that enable owners of condominiums to do what owners of houses have done for decades: rent out extra space.

Towers of basement suites

"Basement suites provide the most affordable housing in the Lower Mainland," said architect and planner Michael Geller. "Some of these basement suites are legal; most are not. Some remain as rental housing in perpetuity; others are taken over by the homeowner as family size increases, or family finances improve."

A longtime advocate of Flex Housing, Geller was president of the SFU Community Trust during the development of UniverCity, a planned community of up to 4,500 homes on 200 acres adjacent to Simon Fraser University.

"Both the university and the City of Burnaby wanted to provide some affordable housing for students within the community. However, the university did not want to use high value land for student housing, especially since it might "de-value" the adjacent condominium sites," Geller explained.

"So the question we asked ourselves was: Why not create the equivalent of a basement suite in a fifth-floor apartment?" he said.

"The answer came from resort architecture. We've all been in a hotel room or suite where, through a series of interlocking doors, two individual rooms can be joined as one suite," Geller said.

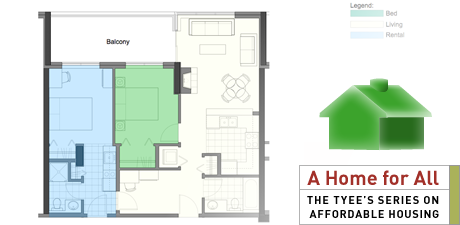

After considerable negotiation, the City of Burnaby amended its bylaws to approve lock-off suites within up to half of the apartments and townhomes at UniverCity. The suites must be at least 240 square feet. They are permitted to have their own entry from the corridor, as well as their own bathroom and cooking facilities.

"When we initially thought of this concept, we expected these suites would be the third bedroom in a three-bedroom unit," Geller said. "However, the first units to be built were in fact two bedroom units, where the second bedroom could either be the master bedroom, or a separate suite."

Twenty-four such suites were built as part of the first development at UniverCity. (See sample floor plan, above.)

"I am quite certain that nowhere else in North America -- or for that matter, in the world -- has another municipality developed a specific zoning bylaw to govern suites within apartments," Geller said. "Burnaby did it in 2002. And Vancouver is looking into it now."

Flexibility does not come cheap

The Burnaby Mountain lock-off suites are not "affordable" in the strictest sense.

In fact, Geller figures they cost between $20,000 and $30,000 more than the same-sized unit with ensuite bathrooms but without lock-off capability. Included in this amount is the extra door to the corridor, more fire-proofing between living quarters, an additional electrical panel and wiring, and parking.

"In order to increase affordability, the city agreed that it would relax its normal parking requirements," Geller said. "Only one space was provided for every four secondary suites."

But the existence of the lock-off suites -- and, specifically, the prospect of their rental income -- has made these relatively expensive apartments more purchase-able, because lenders have regarded a portion of the anticipated rent as income.

"This allows a young family to get into the suite they might not otherwise afford. And later, when kids need their own room, they can take over the whole suite," Geller said.

"Some people would argue that costs inherent in making a home flexible are too great," Geller said. "Particularly recognizing that, at least in North America, we have a propensity to move quite frequently. Others might argue that our propensity to move is a result of the fact that our homes can't change as our needs change."

Filling a gap in the rental market

The lock-off suites have not proven cheap to rent, either. These tiny bachelor suites -- ranging in size from 240 to 285 square feet -- fetch from $525 to $750 per month.

"They rented for much more than I expected," Geller said. "Still, they rent for considerably less than for a conventional one-bedroom suite."

But while the rents are quite high on a per-foot basis, these tiny suites are cheaper than almost anything other than a substandard basement suite or an aging residential hotel.

This may prove to be the lock-off suite's greatest advantage: It serves the most extremely under-served gap in British Columbia's expensive urban rental markets.

In Vancouver, newly built or recently renovated one-bedroom apartments in walkable neighbourhoods rent for about $1,200 a month. Basement suites fetch $750. And a bug-infested room in an aging residential hotel runs to almost $600 a month -- if one can be found.

This leaves students, artists, and other young singles priced out of the market. It also serves as a profound disincentive for the province's tens of thousands of mentally ill and frequently addicted citizens to better their lives: After all, why undertake all the hard work of getting clean if, years later, one is going to wind up shelling out $600 a month to live in the same sort of residential hotel that one lived in on welfare?

A clean, modern suite -- even a miniscule one -- for between $525 and $750 a month is precisely the grail sought after by thousands of single Vancouverites, including many in what Richard Florida calls the Creative Class.

"It's not necessarily affordability in the sense that most people use the word," Geller said of the UniverCity lock-off suites. "But it created a housing choice that would not otherwise have been provided."

Next week: Condo sales king Bob Rennie has views on how to bring down the cost of housing in Vancouver.

Related Tyee stories:

- Michael Geller, New Blood for NPA

Vancouver's reigning party stumbled, says developer who seeks one of its council slots. - Can 'Eco-Density' Be Beautiful?

New initiative means new architecture. But how will it look? - Design the Next Vancouver'

FormShift Vancouver' contest invites new ideas for a vibrant, greener, denser city.

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: