"Let me tell you what it's like at a hearing. I'm in a room, and there's my lawyer in front of me, an adjudicator to my right, two women from the government, and then one or two native counsellors at my side, who I've never met before and who are usually women. Each time, I'm telling this to four different women that I've never seen before, and to an adjudicator who I've never seen before, trying to tell them about things that happened to me way back in 1951."

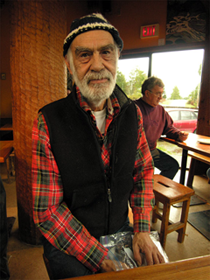

Matthew Williams is a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation. His tribe's main village, Opitsaht, lies across the harbour from Tofino. Williams himself lives on an island off the main village. Opitsaht is just one of many native villages on Indian reserves where former Indian residential school students like Williams are waiting to be compensated for the unlawful confinements and physical and sexual assaults that took place decades ago in the schools.

"They ask me, 'What did it feel like when the priest stuck his penis up your ass for the first time? Did it hurt? Did it bleed? What did it feel like, having him breathing down your neck?' I was eight years old."

Williams travelled to Victoria earlier this month to attend, for the sixth time, a hearing to decide how much he is owed. At the fifth hearing, he was told that this time he would be asked no more than five or six questions. Instead, Williams says, they fired 50 at him within the first hour.

"It is so painful, so shameful, to have to sit in front of those women, time and time again, so they can try to find some discrepancy in my story. It is so degrading, I feel so full of shame. I left that hearing saying 'I don't want your money. That carrot you're dangling in front of me, you can shove it up your ass.'"

In the hours after the hearing, Williams suffered a stress-related anxiety attack. He finished the day in a hospital bed.

Matthew Williams was one of the first residential school attendees in Canada to launch a complaint about the treatment he received while there. His made his first report to the RCMP while he was in an addiction treatment centre. "That was back in 1986," he said last week. "And here I am, 21 years later. I still haven't got a cent."

Only a fraction compensated

Williams is not alone. Out of approximately 100,000 thousand First Nations children who attended residential schools -- about 80,000 of whom are still alive today -- only about 13,000 of the oldest former students have been paid restitution.

That was supposed to change this year. After survivors launched a series of class-action lawsuits, the federal government agreed to a payment formula. But, just as the money was to start flowing, the pipes again got clogged.

A dispute over lawyers' fees means survivors now face even more delays.

The current compensation process was kick-started in 2003 when the federal government, through Indian Residential Schools Resolution Canada, drafted the Alternative Dispute Resolution procedure. The procedure was supposed to serve as a substitute to courtroom hearings and prevent victims, like Williams, from having to face cross-examinations from defence lawyers.

In 2005, a more comprehensive settlement agreement was drawn up between the government of Canada, the plaintiffs as represented by their lawyers, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and the four churches that operated residential schools.

The Agreement in Principle, as the new agreement was called, created a two-part compensation process. The first payment, called the Common Experience Payment, is for all former students and is based on how many years they spent in residential schools, to a maximum of around $40,000. The government set aside $1.9 billion dollars for those payments, as well as another $205 million to fund related initiatives such as the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

The second stage, the Independent Assessment Payment, is for those who were sexually and physically abused. To apply for the second payment, survivors must attend a hearing and talk specifically and accurately about what was done to them. Specific cases of abuse are then classified by severity, frequency and the impacts of the abuse on, for example, their health or ability to earn an income. These factors are then all graded on a points system [for more on the points system see "Putting a Price on Suffering" in yesterday's Tyee] to determine the value of compensation, which could range from $5,000 to $525,000 per person.

That was all decided back in 2005. But, with the exception of small advance payments for the oldest survivors, the money hasn't started to flow. The delay has nothing to do with the survivors themselves and everything to do with their lawyers. Or, more specifically, a dispute over how much those lawyers should be paid.

Feds balk at lawyers' fees

Tony Merchant has become synonymous with the residential school file. Merchant, a well-connected Saskatchewan lawyer, whose wife is a Liberal senator, is the head of the Merchant Law Group. No one disputes that Merchant Law represents more former residential school students than any other firm. Exactly how many, however, is another question.

Under the Agreement in Principle, Merchant Law, and any other firm representing a survivor, is entitled to a fee for every client they represent who claims the Common Experience Payment. (They can also claim a percentage of any award won under the Independent Assessment Payment, an enormous potential windfall for lawyers that you can read more about in part three of this series, tomorrow in The Tyee.) Merchant claims to represent as many 10,000 former students, which he says should entitle him to at least $40 million in fees. The Federal government, though, thinks his roster of clients is considerably shorter and his restitution should be equally curtailed.

The Agreement in Principle included a provision, known as Schedule V, to settle the dispute between the two parties, one part of which allowed the government to hire an auditor to review Merchant's files. But that too caused controversy. The audit, conducted by Deloitte and Touche, ended abruptly in 2005 when Merchant refused the auditors further access to his files, arguing that to do otherwise would be a violation of solicitor/client privilege.

The situation escalated in December, when a judge in Saskatchewan, relying again on a provision of Section V stating that if the Federal Representative and Merchant Law Group cannot come to an agreement on the fees, the final payment "shall in no event be more than $40 million or less than $25 million," ruled that while some of Merchant Law's behaviours have been questionable, the agreement is unambiguous and the government has to pay up, at least to the tune of $25 million.

The federal government, not surprisingly, disagrees. Last month, they launched an appeal of the Saskatchewan ruling, arguing that the judge did not have jurisdiction to make a ruling on legal fees and that the fees themselves should be reconsidered. Until the appeal is settled, the agreement cannot be finalized. And, at least according to Merchant, until the agreement is finalized, no one gets paid.

Minister: appeal won't delay payments

Federal government officials would not comment on this story since the appeal is before the courts. But Indian Affairs Minister Jim Prentice told reporters last month that he doesn't think the dispute would delay compensation payments.

But that's balderdash, according to Merchant. In an interview with The Tyee, Merchant argued the appeal has already caused delays. "This federal appeal will be heard on March 22," he said. "If it takes the judge even just half of the 80 to 100 days the judges took for the previous decisions, it could be mid-May before we reach the next stage.

"We settled this on November 20, 2005. The government promised payments to start in 2006. I now think that we won't see any payments until the beginning of 2008."

Delays kill programs, push back payments

That delay could have serious repercussions on organizations and individuals alike. The Aboriginal Healing Foundation, set up in 1998, was supposed to receive $125 million this year through the Agreement in Principle. Wayne Spear, AHF's director of communications, says he now doesn't expect to see that money until the end of this year at the earliest. 145 funded projects that are presently ongoing will have to be abandoned.

Hearings for individual claims of physical and sexual abuse also cannot begin until the agreement is finalized. While the government has committed to provide resources to hear at least 2,500 cases per year, it is not yet known how many of the estimated 80,000 survivors still alive today will apply through IAP. The entire process, not yet even started, could take decades. Many of the survivors are elderly and sick, and they are dying at a rate of about four every day, according to the Assembly of First Nations.

Breaking the silence

Matthew Williams is now 63. His first payment, under the Common Experience Program, could be another year or two coming. Just by talking about his experience, though, Williams has proved himself an exception.

In Opitsaht, many residential school survivors are still trapped within emotional cages that were created many years ago. All of this talk about forms to fill out, travelling to hearings, telling strangers what happened -- for many people it is triggering memories that have been suppressed for decades. And so, in Opitsaht and the many communities like it, binge drinking (which means forgetting) and talk of suicide (which means escaping), which are already prevalent, are becoming even more commonplace.

"I don't understand why the government won't acknowledge the torture and abuse they put me through in residential school. For 10 years, as a child," Williams said.

"Then along comes Arar. Canada isn't even the one who tortured him, yet they pay. He came back home to his family, and I have to go through this alone, because of how it's made me. Because we were just kids when it happened to us.

"And my settlement, compared to his, will be so tiny. And we're sure not going to get an apology from the prime minister saying 'We're sorry for torturing your son for 10 goddamn years.'" ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: