For many, it's difficult to remember enough noteworthy moments of Canadian civil disobedience to fill the back of the proverbial envelope.

The list might include the Winnipeg General Strike and the Conscription crises. Perhaps there would be a nod to the FLQ crisis, and Oka. The honest among us might add the anti-Asian riots in Vancouver as a tragic moment of misguided civil disobedience.

There are many more, but in the popular imagination at least, the list is short. And for a country swaddled in a myth of peace, order and good government, these noteworthy events have surprisingly violent overtones.

Standing against these is the Clayoquot protest that shook British Columbia and the country 20 years ago this summer. It was a high point in a pitched battle between environmentalists fighting to preserve an old-growth rainforest, along with First Nations fighting for the same and for the recognition of their territorial rights. The battle was against logging companies allied with a labour government dependent on logging revenues -- a provincial government that was briefly the largest stakeholder in one of those companies.

At the time, Clayoquot Sound was the largest lowland temperate rainforest left in the world. For about 10 years leading up to the summer of 1993, it was the subject of protracted land-use negotiations that were punctuated by road blockades and protest.

Finally, in June of that year, Mike Harcourt's NDP government released the Clayoquot Land Use Decision, which set an allowable cut level that environmentalists and First Nations found intolerable.

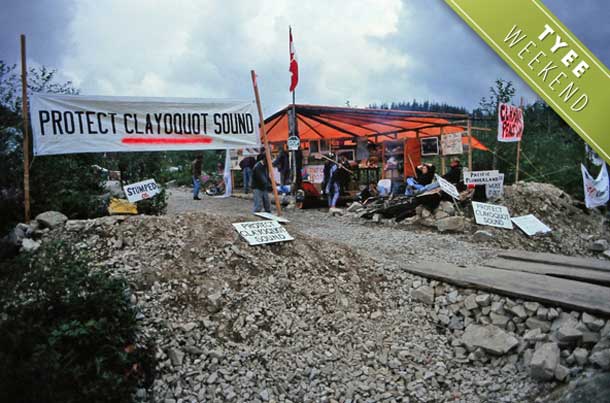

In July, they set up the "Peace Camp" as a place to organize another blockade. Over the course of the next couple of months, it's estimated that more than 10,000 people visited. Much like the recent Occupy movement, the camp fed upwards of 200 people per day, decisions were made by consensus, and educational seminars were held. The camp collective required new participants to agree to a "Peaceful Direct Action Code," which emphasized Ghandian non-violence, no drugs or alcohol, and calm dignity. Leaders were, more often than not, women.

Women like Bonny Glambeck. By the time the '93 protest was underway, Glambeck had already been arrested twice in years prior for her participation in blockades. On probation that summer, she spent most of her time in the camp.

"We had flags flying at the edge of the camp from countries all over the world, representing all the people who had been arrested," remembers Glambeck, a long-time Tofino resident who now runs the conservation non-profit Clayoquot Action. "By 1993, we had gained international attention for Clayoquot Sound."

As the summer wore on, the protest in a remote B.C. forest garnered reportage in the New York Times, which compared it to the fight to save the Brazilian rainforest. Groups gathered in front of Canadian consulates and embassies around the world to voice their solidarity. Before he was a failed presidential candidate, congressman John Kerry wrote a letter to former vice-president Al Gore urging him to pressure Harcourt to relent to the protestors' demands. Robert Kennedy Jr. was helping local First Nations. A Belgian member of Parliament joined.

In the end, it was one of the largest moments of peaceful civil disobedience in Canadian history. More than 900 people were arrested, which led to the largest mass trial in Canadian history, if not the Western world. All because some folks wanted to stop large companies from turning thousand-year-old cedars and hemlocks into, among other things, non-proverbial envelopes.

'Very changed lives'

In addition to changing forest practices in B.C., the protests changed lives. It propelled some into the spotlight, radicalized others and made and destroyed careers. More so, it created a cast of characters that became notable players on the political stage -- many of whom gathered in Tofino this weekend to celebrate the anniversary and warn of future threats. The event is organized by Friends of Clayoquot Sound, which spearheaded the '93 protest.

"There has been logging that has continued," acknowledges Valerie Langer, co-founder of ForestEthics, who was a key organizer in the woods that summer. "Some places that are very special have been lost. Some battles you win, some you lose. But the big blockade of 1993, that's one of the things that delineates a watershed moment for Clayoquot Sound and for the environmental movement in B.C."

Langer helped found Friends of Clayoquot Sound shortly after arriving in Tofino in 1988. She believes the group's peaceful tactics helped inspire greater numbers of people to join the movement.

Friends of Clayoquot Sound's early blockades involved trekking out into the wilderness -- "an hour by boat and a hike up the cliff" -- with a few other volunteers to get to a logging road under construction, Langer recalls. Only the hardiest could possibly get there.

Unsurprisingly, these yielded little success. The group decided to take a different approach. They selected a site accessible by car and accepted that while they could not stop the logging (each day, blockaders were arrested to let trucks roll through), they could make a symbolic stand.

Thousands of people joined them. One highlight, Langer says, was the day a burly logger showed up at the group's office.

"He said, 'I've come up with 10 people who work in the forest industry and we have a banner and tomorrow morning, we want to do a blockade of forest industry workers against unsustainable logging.'"

Subsequently joining in were doctors for Clayoquot Sound, artists for Clayoquot Sound, disabled people for Clayoquot Sound. "It was a symbol," says Langer, "for everything that people wanted to see done differently to protect the environment."

The experience bonded those working together, cementing lifelong friendships.

"We started off working out of a passion for the place where we lived, and we ended up, many of us, with very changed lives," Langer says.

One of Langer's close allies was Tzeporah Berman. Arrested that summer "literally off the side of the road" as she remembers it, Berman was charged with 857 charges of criminal aiding and abetting for her participation in the blockade.

(At that time, Berman was not yet known as a Canadian "enemy of the state." That honour was bestowed upon her a few years later by former B.C. NDP premier Glen Clark, who wasn't much a fan of the young activist's efforts to stop clear-cut logging in the Great Bear Rainforest.)

Despite a prison stint and the two long years of court proceedings -- the charges were eventually dismissed -- Berman said her involvement as a captain of B.C.'s war in the woods represents a critical turning point in her life.

Her career since has been both driven and defined by her convictions. From a top Greenpeace campaigner in Europe tasked with persuading executives to green their business practices, to co-founder of ForestEthics, a group which claims to have "helped move billions of dollars of corporate buying toward environmentally responsible market solutions," she rose the ranks from student activist to become a woman Reader's Digest called one of the world's most powerful environmentalists -- Canada's "Queen of Green."

"I do the work that I do because of the deep influence that summer had on me," Berman says, "and my lasting belief in the power of civil society organizing to balance the undue influence of corporations on public policy."

Arrested too was Svend Robinson. A long-serving NDP MP at the time, Robinson arrived at the blockade on day one, hoping his presence would attract media attention to the issue.

The next federal election was mere months away.

"The stakes were high," Robinson says. "But I felt so strongly about the loss of this magnificent old growth forest, one of the last remaining on Vancouver Island, and the contempt for aboriginal rights."

Robinson was later charged for contempt of court and sentenced by Justice Wally Oppal to 14 days in jail. But though fellow politicians and forest union leaders criticized his role in the protest, he was re-elected in his Burnaby constituency in 1993 and remained in politics for another decade.

"I look back on the blockade with great pride as an incredibly powerful act by a wonderfully diverse group of people from around the world," Robinson says.

Glambeck, Langer, Berman and Robinson converged once again in Tofino this weekend to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the blockade, along with several other key players, such as Elizabeth May, the Green Party of Canada's leader; John Cashore, the 1993 B.C. minister of environment, and Joe Martin, a Tla-o-qui-aht master carver. Countless more were in attendance.

On this anniversary weekend, The Tyee invites you to share your remembrances of the 1993 Clayoquot protest in the comment thread below. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: