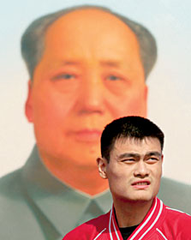

Now that the Beijing Olympics draws near, let's talk about the Chinese view of the body, how it went from Mao to Yao Ming, that is, from a culture of collective thinking to that of singular, athletic and glamorous.

Indeed, in modern China there came a startling moment when everything altered and shifted. A man carrying two plastic bags, one in each hand, stood directly in the path of a column of armored tanks, effectively preventing them from proceeding down the avenue toward Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The day before, on June 4, 1989, hundreds of pro-democracy students and workers had been gunned down in and near the square.

The image of "Tank Man," as he's now called, stays indelibly in the mind. For a brief moment he managed to stop the machines with just his body. This unknown rebel, unarmed, stood up against the awesome power of the state and, as the world watched, gained something priceless in return: He liberated his body from the collective, from being subservient to the ideological machine, and opened the floodgates to a new world.

Although direct political confrontation failed, a new sideways rebellion began in the cultural and economic sphere, one that has succeeded. If Mao launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966 to be rid of "liberal bourgeois" and to continue the revolutionary class struggle, the bourgeois liberals have struck back. The real cultural revolution, stoked by individual desires and ambitions, is happening now. The "We" of the old traditional world of clanship, self-defined by proper behavior and relationships within the collective, is ceding to the "Me" of the new generation, one defined largely by sex.

Under the knife

In a 2007 poll by Renmin University of China, more than half the Chinese surveyed in 10 provinces found premarital sex acceptable. Only 12.8 per cent said it was immoral. And the Internet, to which 200 million now have access in China, has flung open the bedroom door. While the government cracks down on online political dissent, the new socialism allows for a great deal of personal expression.

The proliferation of spas, sports clubs, fashion magazines and shows, beauty products, massage and dance clubs, love hotels, talk shows about sex, underground porn, and obsession with athletes and movie and pop stars all speak to the glorification of the body -- in stark contrast to the Cold War era, when having too big a mirror in one's home or even wearing makeup in public could be deemed counter-revolutionary.

Most telling is the growth of the cosmetic surgery industry.

In recent years, more than 10,000 clinics have opened. The number of surgeries for straighter noses, double eyelids, and breast augmentation would suggest that a fair number of Chinese with disposable incomes are rushing for extreme makeovers.

Body without glory

In ancient Rome and Greece, the naked body was sculpted to perfection and generally glorified. During the Renaissance, the human form was rendered not only anatomically correct but profound in refined drawings and paintings. In China, however, the body was kept hidden until the dawn of the 20th century.

To be sure, there were erotic images in ancient China, but they were created during the Taoist-dominated eras as manuals to educate young married couples. Far more typical were the paintings that depict upper-class men and women perched on carved wooden chairs, their hands hidden in the sleeves of beautiful brocades, their faces stoic, inexpressive, like peg dolls. To project a cold, outward face was akin to moral rectitude.

"The human body in traditional China was not seen as having its own intrinsic physical glory," notes China scholar Mark Elvin, author of Changing Stories in the Chinese World. Beauty was not dependent on sexual characteristics and attributes, he observes, but on artifice and ornamentation -- a painted face, silk brocade, the jade bracelet that dangles from the wrist -- or alteration such as the painful and crippling binding of feet.

Western gaze

Contacts with the West changed all that. The presence of the pale-skinned, blue-eyed gwai lo, "foreign devil," forced a new kind of self-awareness on the East. Take the beautiful cheongsam, a body-hugging piece worn by Chinese women. Developed in cosmopolitan Shanghai around 1900, it originated from its opposite, the qipao -- a baggy and loose-fitting dress once meant to de-emphasize and conceal the wearer's figure, that was transformed in the final years of China's last dynasty to reveal curves, waist, bosom, and a lot more skin.

Along with the colonial-era concept of the body as an object of admiration came a more insidious metaphor perpetuated by Westerners: the "sick man of East Asia." It was reinforced by caricatures of the frail, opium-addicted Chinese man with a long pigtail. Chinese defenselessness carved a deep wound in the collective psyche. Not surprisingly, the Boxer Rebellion, a peasant-based uprising in 1899-1901 against foreign influence, had at its heart the belief that the body can achieve invincibility. The rebels were practitioners of martial arts, which they believed could help turn their bodies into armor, impervious to bullets. That the rebellion failed and the bullets did pierce their flesh did not extinguish this collective longing for inviolability. The theme of Chinese martial arts as the antidote to Western conquerors' firepower continues to inform and inspire many martial arts films, novels and comic books.

Under Mao, the body was once more inducted to represent the nation. In propaganda posters that have become collectors' items, workers are depicted as strong and square-jawed; athletes are lithe and agile. Sports became synonymous with modernity. A strong body was reflective of national strength and was seen as necessary for unity. The self was in service to a larger cause, and everyone moved together wearing Mao jackets -- a sea of blue and gray. The body, subdued by ideology, was not yet free.

Shame vs. 'Tank Man'

Freedom arrived in the late 1980s, and its symbol was that singular image of "Tank Man" engaging in a brazen and courageous act of self-expression. Once unleashed, though, freedom created a ripple effect that surged through the culture and threatened to wash away hundreds of years of social mores -- the piety of Confucianism, the humiliation of Western imperialism, the righteousness of communism under Mao, all variants of a single unifying characteristic: shame.

"Lead the people with excellence and put them in their place through roles and ritual practices, and in addition to developing a sense of shame, they will order themselves harmoniously," Confucius said in his Analects. Shame, in other words, binds the tongue and inhibits behavior.

Those who seek to change the old world order, therefore, learn to be shameless. Lewis Hyde, in his seminal book Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art, noted that artists who seek to change the conversation of the culture refuse "their elders' sense of where speech and silence belong, they do not so much erase the categories as redraw the lines."

Take the 2004 photograph "Hindsight" by the artist Liu Wei, in which a misty black and white image of a mountain scene is in fact made up of naked rear ends. It is both at once aesthetically pleasing and oddly lewd.

Or consider the controversial body art showcased in Shanghai in 2005, in which traditional brush paintings were drawn on naked models. Images of mountains and rivers, of peonies and songbirds, suddenly migrated from the familiar old canvas onto a moving one made of human skin. Most compelling was the female model who had a blue cheongsam with white crested wave motif painted on her body. She is both beautifully clothed and astonishingly naked -- and a literal transfiguration of the past.

Indeed, that old sea of green and gray Mao jackets has been rapidly transformed into a field of a hundred thousand flowers blooming. Protesters in Tiananmen Square may have failed in their direct confrontation with the state, but in their wake there rises a culture all at once playful, shameless, and disruptive of the past.

Related Tyee stories:

- Stepping Outside the Bamboo Lines

Interview with Jen Sookfong Lee, author of 'The End of East' - The Face of Asian Mixed Marriage in BC

All about 'NAAAPs, CBCs, and Egg-Yellows' - China's Sexual Revolution

A nation's sleeping libido awakens.

Read more: Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: