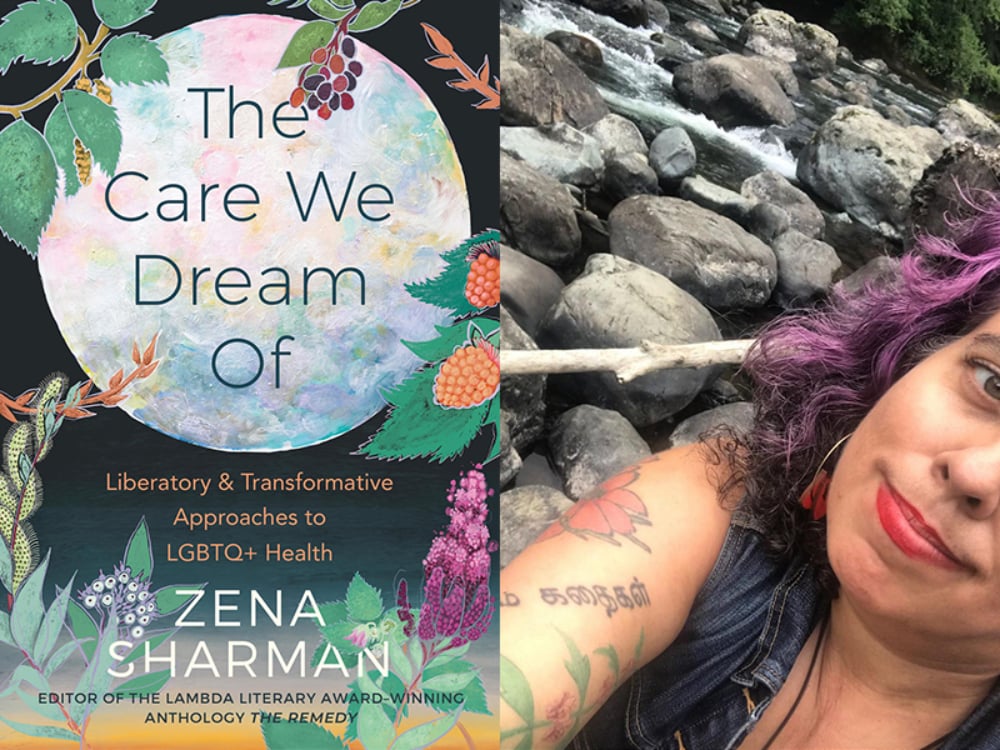

[Editor’s note: This excerpt, from Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s 'Cripping Healing,' can be read in full — alongside writing by Zena Sharman, Alexander McClelland and Zoë Dodd, jaye simpson, Jillian Christmas and more — in 'The Care We Dream of: Liberatory and Transformative Approaches to LGBTQ+ Health' out now with Arsenal Pulp Press. The book begins with a question: What if queer and trans people loved going to the doctor? From there, editor Zena Sharman, whose previous works include 'The Remedy: Queer and Trans Voices on Health and Health Care' and 'Persistence: All Ways Butch and Femme,' imagines liberatory futures for health care, futures that aren’t limiting but rather take a view of health as 'wholeness, healing, happiness, safety and sacredness.' If this all sounds theoretical and you’d like to understand what this kind of reimagining can mean in practice, you’re in luck: this excerpt does just that.]

Can you write me a prescription for my own accessible apartment?

We’re used to thinking of “healing” as specific treatments — surgery, pills, herbs, acupuncture. Those things are useful and important. But a cripped definition of healing would include anything that supports someone’s disabled body/mind. My cane; my friend’s garden bench chair they sit on while they weed; my heating pad and excellent ice packs; my friend’s sensory friendly hijab; the CRV my friend and his partner bought that can easily fit his wheelchair in the back; stim toys; my car with its disabled parking permit; the disabled parking spaces at the Grocery Outlet; the portable wheelchair at the protest; Zoom captions; the autistic Black, brown, Indigenous, Asian and mixed race group I hang out in online; and my close and extended disabled BIPOC friend family who are available to bitch and vent and commiserate and troubleshoot and doula each other: none of these are healing in the “cure” sense. But all of these things do a lot to ensure my or someone else’s chances of an excellent disabled life.

The items I use on that list are not things I knew I needed overnight. They emerged from a process of defining what healing looks for me as a disabled person, a process that’s ongoing as I grow and my disabilities grow and change, too. It’s a process whose goals are less about “curing my chronic illness” — which, like most of them, doesn’t have a cure — and more about “less pain, adaptations that stretch my spoons, monitoring growths and illnesses early, and creating a sensory-friendly environment.”

Figuring out those goals would not be possible without having disabled friends and disabled community who could do what disability justice activist Stacey Park Milbern referred to in my conversation with her in Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice as “crip doulaing” — the process by which disabled people mentor other disabled people in learning new disabled skills, from how to drive a wheelchair and negotiate with care attendants to how to have sex. She points out that until she invented the term in 2017, there was no word to describe this process of disabled-to-disabled mentorship and skill-sharing. And if you don’t have words for something, it’s hard to do it or imagine it’s possible.

Both when we have a crip community and when we live in isolation, sick and disabled people are inventive and creative as we crip healing, and the ways we create to heal aren’t ones that fit in most doctors’ rule books. We know what we need, including when it looks wrong or silly or “crazy” to other people. The crip healing we create might be a freezer full of gluten-free frozen pizza and tater tots for high-pain, low-spoons days. It might be a Mad Map — a document similar to advance directives, written by a Mad person describing what their altered states or crisis times look like and stating their needs, preferences and boundaries for when they go into an altered state. It might be turning our phone off and going to the woods when we go into an altered state, temporal access, or a million hours of The Office cued up on Netflix. After 15 months of severe back and hip pain, the sports medicine doctor I saw could only furrow her brow and push weight loss and more tests; I had a 90-per-cent pain reduction through using the McKenzie Method, which a disabled fat femme I knew mentioned on Instagram. (The method includes books such as Treat Your Own Back and Treat Your Own Hip.)

One of the biggest cornerstones of my own crip healing has been my ability to rent my own place — to live by myself, where I can cry as much as I need to, make tea with no pants on, look weird, be tired, keep the place as clean as I need but also, it’s not a big deal if things get gross for a minute. Living alone has given me the autistic quiet I need to thrive, a place where I don’t have to mask or negotiate my access needs with anyone. This is vital, for me and so many other Mad and neurodivergent folks. Yet you won’t see the right to live alone in a messy, accessible, affordable apartment on any doctor’s prescription pad.

Cure ≠ healing

In his book Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure, white disabled trans activist and writer Eli Clare writes about cure from every angle — how ideas of cure were invented by colonial western doctors, settlers and capitalists; what purposes cure serves and where it fails us; and what a disabled vision of a good life might be if we decentred cure. On page 25, he writes, “At the centre of cure lies eradication,” of what he terms “brilliant imperfection” — all the skills, brilliance, ideas, art, community and love that disabled people create because, not in spite, of our disabilities. (Quotations from this book reprinted with permission.)

There are so many examples of the harm that comes from lifting up a cure model as the only way to fly, like how the medical industrial complex pushes treatments like applied behaviour analysis, or ABA, on autistic children. ABA was first developed as a form of aversion therapy to “cure” queerness. It’s now one of the most common treatments parents of newly diagnosed autistic kids are told they have to use on their kids. In ABA, autistic kids are punished for exhibiting visibly autistic behaviour, like stimming, not making eye contact or not speaking verbally. ABA literally uses the phrase “compliance training” in its pushing of autistic young people to stop acting autistic, setting us up for lifelong vulnerability to abuse — if you can’t trust your gut when it wants you to act neurodivergent, how can you trust it when it tells you a partner or friend is abusing you?

Although there are not a ton of studies backing this up — because the vast majority of funding for autism research is focused on “curing autism” rather than being led by or learning from neurodivergent people — there is a vast amount of anecdotal experiences shared among adult autistics reflecting on the lifelong damage ABA caused us and how we would have benefited much more from access to autistic community, access supports like alternative communication devices and sensory-friendly environments, love and acceptance. The website Stop ABA, Support Autistics: Advocating for Better Treatment of Autistic Individuals crowdsources information about why ABA is harmful, and what works better.

Cure often also just doesn’t work! Telethons have been raising money to “cure” diseases for years, but they’re still here. And how many of us could trust the cures that are promised? Clare writes of his encounters with many doctors throughout his lifetime who promise that any day now, they’ll be able to “cure” his cerebral palsy and his retort to a recent one, shared on page 85: “Not over my dead body. You can’t even explain what happens between my brain and my muscles.” On page 90, he writes of how telethons to “race for a cure” are so much more common and funded than events like Zoe’s Race, an annual fundraiser held in Burlington, Vermont, where people roll, walk, and run, fundraising to make homes more disability accessible:

Erika Nestor founded the event after she and her family renovated their home to make it more accessible for her disabled daughter, Zoe. Along the way, she learned just how expensive this kind of remodeling is and how little funding exists to help people make it happen... Zoe’s Race is motivated by the value of accessibility rather than cure. The money raised goes to something concrete, improving people’s present-day lives, rather than something intangible centred on the future.

Clare also complicates his anti-cure politics, writing on page 13 about his friend with cancer who says, “I’m not at war with my body, but at the same time, I won’t passively let my cancerous cells have their way with me.” On page 61 he quotes disabled feminist thinker Susan Wendell, who says, writing about living with chronic pain, “Some unhealthy disabled people... experience physical or psychological burdens that no amount of social justice can eliminate. Therefore, some very much want to have their bodies cured, not as a substitute for curing ableism, but in addition to it.”

Because that’s the thing. We need both love and acceptance as we are as disabled and total access to the life-saving health care we need. Many of us really need access to western medicine — surgeries and transplants and drugs and chemo and wound care and equipment and western science. And some of us die without it.

Happy holidays, readers. Our comment threads will be closed until Jan. 3 to give our moderators a break. See you in 2022! ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice