Poor old Barbara Kruger. The New York artist came to fame in the early 1980s when her image and text convergences caught the flavour of the moment. Her most infamous work featured “I shop therefore I am” emblazoned in white Futura font on a red background. In the go-go ‘80s and early ‘90s, Kruger’s full-throated fusillade against consumerism seemed downright revolutionary.

Flash forward seven years, and Kruger’s iconic red box with white text is taken up by a skateboarding company, which parlayed her typography and colour scheme into a worldwide fashion brand known as Supreme.

When the Carlyle Group, a global investment firm, bought a 50-per-cent stake in Supreme, the deal was estimated to be worth $1 billion. In the fall of 2020, the company sold its ownership share for $2.1 billion.

I would venture that Kruger never saw a thin dime of this money.

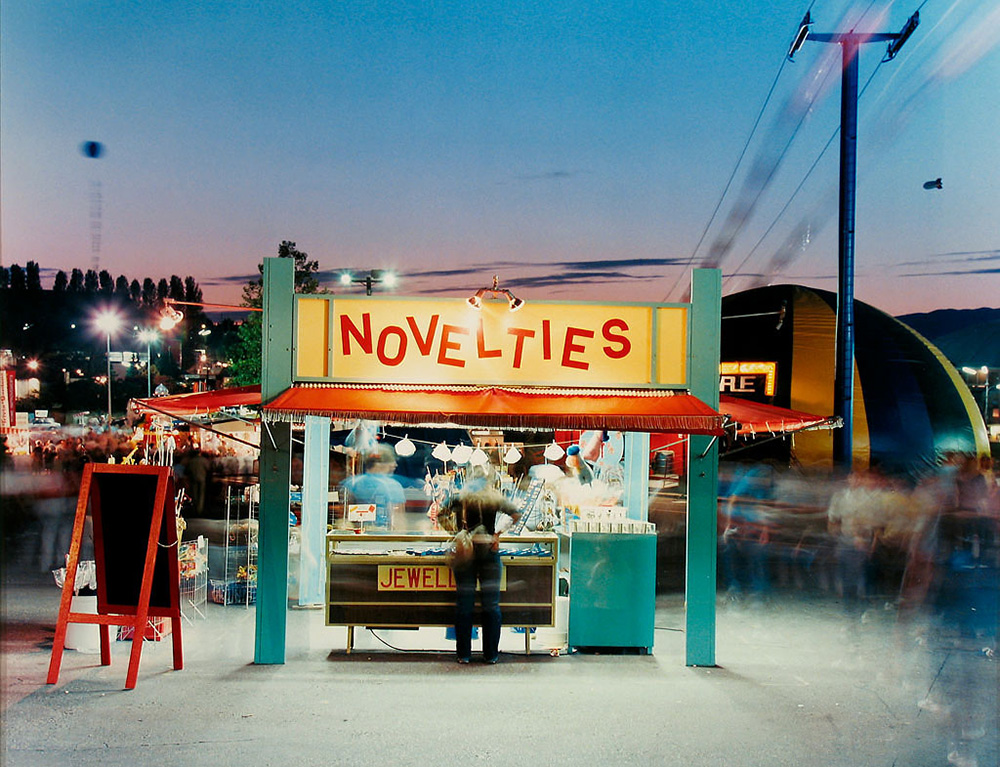

What does this have to do with anything? This story is emblematic of the strange relationship between art and marketing that’s at the centre of Pictures and Promises, a new exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

It’s a weird marriage, part mutual exploitation, part genuine affection. But as the Kruger/Supreme saga makes clear, this polyamorous conjunction is nothing new. Pop art and advertising have been messing about with each other for a long time, and now you practically have to pry them apart with a crowbar.

Does the VAG show offer anything new about this chumminess? Not really. But it does raise a few questions about the continued intertwining of art, commerce and value.

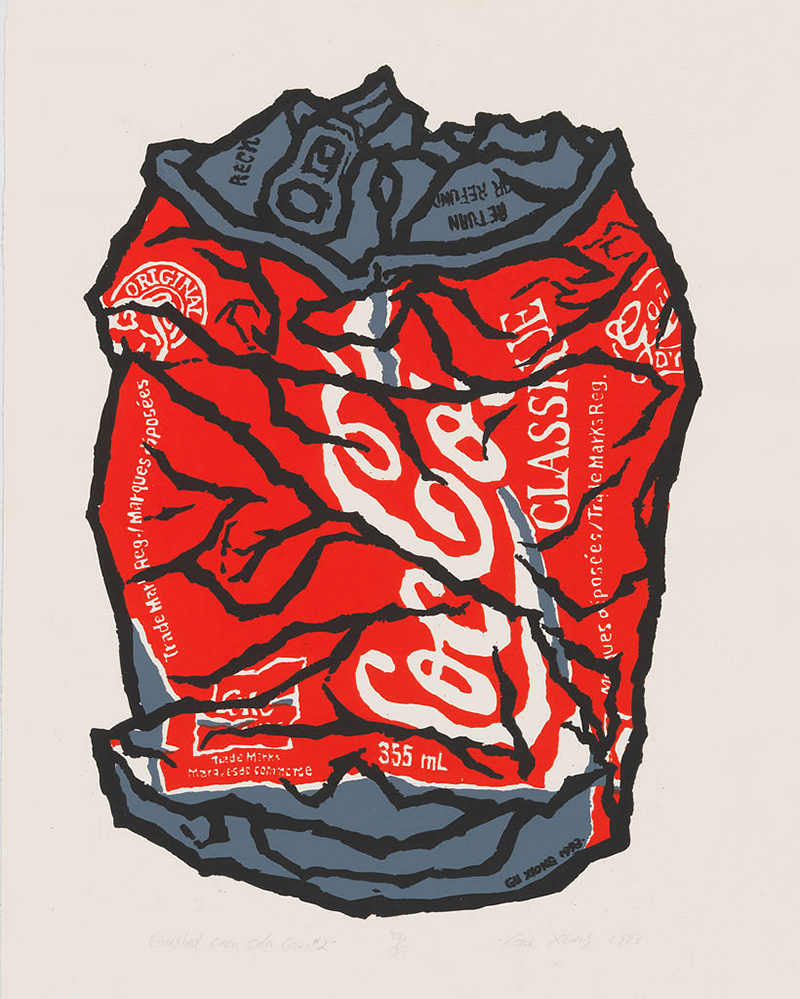

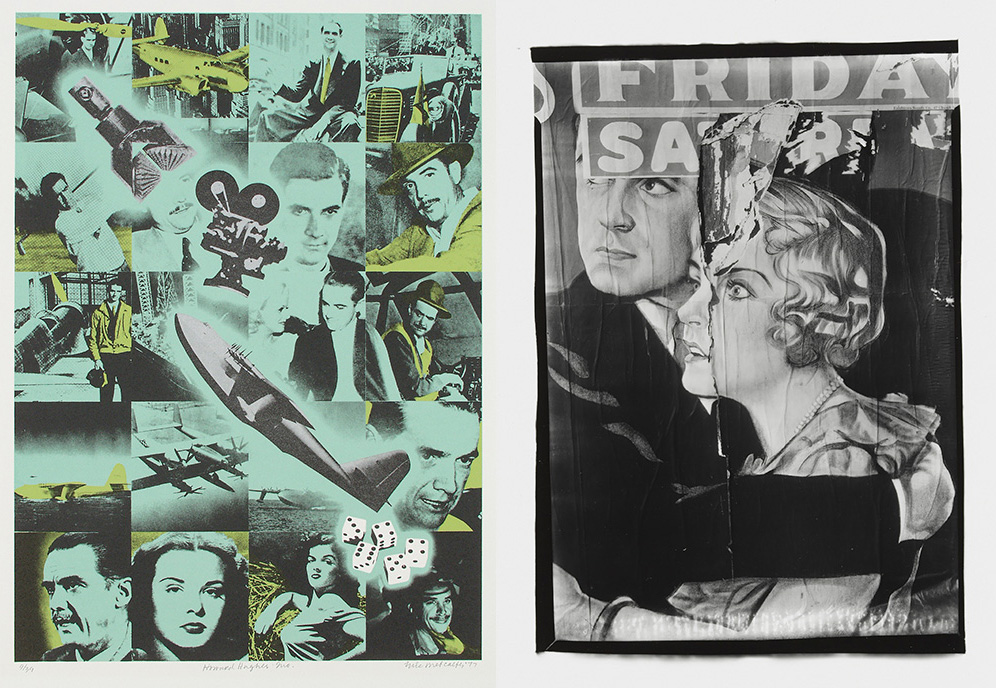

The exhibition is a curious cherry-picking of images that are simultaneously informed by marketing as much as they are subversions of it. It includes Kruger’s work as well as assemblages by Ken Lum, Vikky Alexander’s fashion mag blow-ups, and work by Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, Walker Evans and Gu Xiong.

The title of the VAG exhibition takes inspiration from Kruger’s 1981 show: Pictures and Promises: A Display of Advertisings, Slogans and Interventions. The original exhibition was a mashup of TV commercials, ads, posters and signage from artists like Cindy Sherman, Jenny Holzer, Richard Prince and Andy Warhol.

The things that were at issue then are still at issue now. As the review of the original 1981 show in Artforum declared, the line between “art and commerce were indistinguishable.”

But as critic Carrie Rickey went on, this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing: “Why defend artists’ poaching off the mass market if you can’t countenance the reverse? Probably because ‘slumming’ is respected social behaviour, while upscale moves are viewed with suspicion, with taunts of ‘Carpetbagger!’”

In other words, artists have long drawn upon the world of advertising for inspiration, just as the fashion, marketing and their related industries have lapped at the teats of the art world.

Kruger herself was inspired to create her original textual works after a stint working at Mademoiselle magazine making mailorder ads. Warhol did time in the advertising trenches. Salvador Dali infamously designed the packaging for Chupa Chups lollipops. Cindy Sherman has collaborated with Prada to create fashion campaigns. Ken Lum honed his art chops painting signs. So, the division between these two worlds is paper thin, shall we say.

High culture chews on low. Mass culture purloins high. Art and commerce have poached from each other so much that it’s occasionally hard to say what differentiates the two.

In this aspect, the incestuous relationships on display at the show are pretty rich and loamy stuff. They’re also a bit funny.

After being ostensibly ripped off by Supreme, Kruger offered a blistering riposte with a series of exhibitions that called out the appropriation game. She branded her own skateboards, T-shirts and hoodies with messages designed to skewer the commodity fetishism of the fashion world.

But it’s hard to conceive of a better form of inverse justice, than Supreme suing another skateboard company for copyright infringement for making use of the white font/red box style that Kruger created.

Supreme’s pinching of her stuff was one thing, but the perversity of suing someone else for doing exactly the same thing caused Kruger to weigh in. “What a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers... I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce. I’m waiting for all of them to sue me for copyright infringement.”

That Kruger’s most famous works calling out rampant consumerism were subverted by an upstart skateboard company that became among the most coveted brands in the world makes for the ultimate art farce. It’s an idea that David Shapiro, author of Supremacist, describes as a “long-term conceptual art project about consumerism and theft.... And corporate ownership.”

But who’s using who?

In spite of its pilfering ways, Supreme has collaborated with a number of contemporary artists, as a 2017 Vogue magazine profile of company founder James Jebbia noted. “The list of artists who have worked with Supreme over the last two decades could fill a gallery space: Christopher Wool, Jeff Koons, Mark Flood, Nate Lowman, John Baldessari, Damien Hirst — even Neil Young.”

Naturally, Kruger was not on the list.

One might argue that advertising is, in some fashion, a wee bit purer than the art world. After all, it’s clear in its intention — it wants to sell you stuff. Whereas the art world is more slippery in its ambitions. It’s about money and cachet, but it also wants people to have feelings and thoughts. But the art world may, in fact, be the original Hypebeast creator.

In order to justify sky high prices, the idea that a work of art is singular, rare and covetable must be sustained above all else. It’s a brutal lesson that was hammered home in Nathaniel Kahn’s documentary The Price of Everything, which traipsed along with curators and art dealers as they sucked down free wine at openings and drove up prices.

The lesson applies equally well to the fashion industry. Desire is steeped in rarity. Access or lack thereof is everything. Supreme’s marketing model was based on releasing limited editions of merchandise, driving a ferocious need to have something that few others had. The brand created and dropped new offerings in their stores on a weekly basis.

If you didn’t physically line up for three days to buy a box logo T-shirt, you were out of luck. You could pick one up later, at exponentially jacked up prices, if you were lucky. At the height of the Supreme frenzy, flipping the brand’s merchandise was an active and very lucrative business.

I’ve seen it in action at the Supreme store in Paris. The Paris outlet is not unlike visiting a gallery, with long lines, multiple security guards and a pronounced air of exclusivity.

Supreme isn’t the only fashion company to make active use of the art world. The collaboration between Japanese artist Takashi Murakami and Louis Vuitton created a line of insanely coveted handbags and accessories.

The Italian design house Prada also mixed culture and fashion in innovative fashion.

Prada has moved into funding films made by female directors. Many of the filmmakers in the series, such as Ava DuVernay, Chloë Sevigny, Isabel Sandoval and Mati Diop, are staggering artists.

But as much as there is mutual exploitation on both sides of the art/commerce relationship, some good and even great things can emerge from the coupling. Although Pictures and Promises doesn’t add a great deal to what has been readily apparent since Warhol was making Campbell Soup cans, it’s nevertheless a fun romp in the art hay, as long you don’t take it too seriously.

As Barbara Kruger once said, “Listen. Our culture is saturated with irony whether we know it or not....” A statement that can be applied equally to the worlds of fashion, marketing and art.

'Pictures and Promises' runs until Aug. 22. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: