In the world of drawing, Betty Edwards is a goddess. Her seminal book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, first published in 1979, made the case that anyone could learn how to draw. Over the last few decades, Edwards demonstrated the truth of this claim with five-day workshops that offered a fundamental understanding of not only how to draw, but more importantly, how to see.

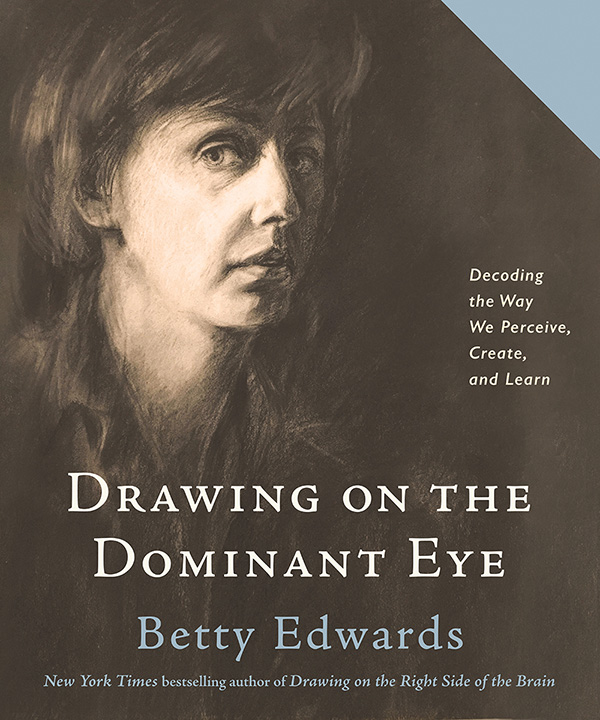

At 94, she is a joyful, ebullient presence as we talk about her new book, Drawing on the Dominant Eye: Decoding the Way We Perceive, Create and Learn. The concept of a dominant eye, “eyedness” for short, was news to me. Like being right or left-handed, it turns out that humans also have a dominant eye.

The book offers a few simple tests to figure out which eye rules the roost in your own head. Some 65 per cent of the population are right-eye dominant, and 34 left-eye dominant. In one per cent of the population, both eyes are equal.

Archers, marksmen and others have long known about eyedness, but we all have an unconscious understanding of it. When talking with another person, people tend to look into their dominant eye — speaking eye to eye, as it were.

Edwards first noticed the phenomena while teaching portrait drawing to neophyte students. Before instruction, students tended to draw eyes as symmetrical, but after lessons they drew eyes with clear differences.

It’s not simply the eyes themselves, but what they represent in terms of brain function that is most fascinating. As Edwards explains in the introduction to her book: “The dominant and subdominant eyes reveal the mind.”

The concept of eyedness is a leaping off point for an intriguing journey through a broad array of ideas — everything from politics to the pineal gland, which produces melatonin in the body. In undertaking these explorations, Edwards is an excellent guide — curious, funny and able to pull out the unseen connections between things.

Before reading her latest book, I’d never thought about this aspect of human physicality, and now I can’t stop thinking about it.

The right eye, connected to the left hemisphere of the brain with its emphasis on words, logic and reason, is bright, inquisitive and fixed intently on whatever its gaze lands upon. The left eye, by contrast, is dreamy, less assertive and wired into the right brain with its nonverbal, intuitive approach to the world. A number of illustrations, portraits and photographs throughout the book make these differences clear.

The different aspects are best summed up by two quotes in the book’s introduction. As painter Paul Klee says, “One eye sees, the other feels.” As photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson observes, “One eye looks within, the other looks without.”

These distinctions manifest in fascinating ways. When painting female models, for example, male artists have a tendency to paint the softer, less dominant left eye, letting the questioning right fade into the background. Conversely, when painting self-portraits, artists like Picasso favoured the dominant right eye, making them seem more alert and assertive.

There’s a lot packed into this book, all elucidated in Edwards’ clear and precise prose. One of her main goals is to be clear, she says. “When I’m agonizing about how to put something into words, [I think], ‘Oh, just say it, Betty!’”

Anyone who switches back and forth from writing to drawing has probably experienced the occasional frustration with words. Words and sentences must be constructed and built like a wall, whereas drawing often feels much more fluid, like a river.

In a culture that values speed, efficiency, facts and numbers, the left brain, with its ability to name, label and verbalize has long been valued over the right brain. Even in their early education, children are taught how to read and write, but not how to draw.

But as Edwards asserts, learning to draw has untold benefits, not the least of which is a greater understanding and appreciation of the world. She quotes Daniel M. Mendelowitz’s famous book, A Guide to Drawing: “That which I have not drawn I have not seen.’” And when she asked workshop participants whether the class changed them, the answer was often “I see things I’d never noticed before.”

It’s a different way of understanding the world, a slow seeing as opposed to the quick naming, and it’s fundamentally about empathy. To draw something, be it a tomato or a human being, is to develop a relationship with the thing being drawn. As Edwards laughingly says, she often feels like saying “I’m in with love you!” after drawing her students over the years.

This type of empathetic relationship is often surprisingly nonjudgmental. Anyone who has done a lot of life drawing knows that imperfect bodies are more interesting to draw. Wrinkles, lines and bulges are much more engaging than symmetrical faces and perfect pectorals.

There are other significant pleasures derived from drawing, like escaping to an older way of understanding and perceiving the world. Right-brain activities tend to be timeless and quiet, a break from the endless chatter of the left brain. “Drawing can be a huge relief,” Edwards says, especially during times of stress and anxiety.

It’s hard to say if people are drawing more during the pandemic. But if something like Portrait Artist of the Week is any indication, perhaps so. The program was a pivot from the U.K. Sky Arts channel’s long-running series, Portrait Artist of the Year.

When the pandemic hit, the program offered a weekly drawing session that anyone could join. Submissions flowed in from around the world in an explosion of creativity and celebration of the art of observation.

The richness of this outpouring is a powerful reminder that anyone can learn to draw at any age. It’s not about innate magical talent, but the willingness to look and understand. In this fashion, drawing dates back to the earliest manifestations of human culture.

Edwards notes that visual language long predates the written word, using examples of prehistoric cave art that captured the intricacy and beauty of the natural world. But as images evolved into symbols and, eventually, language, she argues something went awry. “Drawing, which contributed greatly to the invention and perfection of writing, has in the process been largely overwhelmed by language and become lost as a form of human intelligence and expression.”

With the ongoing attrition of creative education, drawing isn’t a part of curriculum. Even something like cursive writing isn’t taught anymore, a fact that Edwards finds confounding. The days of pride in penmanship, the struggle to make an elegant capital "G" with its curlicues and flourishes, is gone, she says, and even personal signatures aren’t what they used to be.

Still, the fact that certain symbols have stood the test of time shows their importance. None have been around quite as long as the Eye of Horus, an Egyptian hieroglyphic that researchers believe is a visual representation of the pineal gland, the brain system that Descartes called the “the principal seat of the soul.”

The third eye, as it is referred to in other cultures, might actually be a vestigial eye, deep within the brain itself. Edwards cites a 2015 U.S. study that made the case. “[The] findings suggest that the pineal gland is a precursor to the modern eye, with photoreceptors present in both organs, and that the gland is the ultimate third eye, embedded in the brain itself.”

There’s a reason the all-seeing eye is still on the U.S. dollar, or that one of the most popular tattoo designs continues to be an eye. It is a portal through which we travel, both in and out, from the Platonic cave of the skull. Although Edwards’ book is packed with some high-flying ideas, it is also deeply rooted in the real, the observable and the practical, offering a variety of drawing exercises.

At the centre of her thesis is the idea that right and left hemispheres function best in a holistic fashion, working in concert, each supporting the other in their respective strengths. “Learning,” as she quite rightly says, “never harms, it only helps.”

Drawing offers a kind of relationship not only with other people and the observable world, but also with your own mind, bringing the two halves together to form a whole. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: