I grew up riding horses, then bicycles. I also grew up knowing that if you are an Indian that can pass as not being an Indian, you don’t talk about it — if you don’t have to.

Today I am an Indigenous professor who has the amazing privilege of helping Indigenous graduate students navigate the labyrinth of one of the world’s great research universities.

How did I get here? I ask. I don’t know really, but here is a story that is part of the answer. This story has four main characters, my father, my childhood best friend Tom, and Tom’s dad Ray. I am the storyteller who wanders in and out of scenes.

My father was a letter carrier for the United States Postal Service in Washington state. He thought I had taken his exhortation to go to college much, much too far. Three years ago, just before he died of congestive heart failure, he said to me, “Son, I have seen enough. No, I have seen too much. I am weary now and ready to move to another realm. I have seen what I never thought could be. I never would have believed that I might accumulate the impossible number of 87 years.

“I’m ready now. I have seen the Cubbies win the World Series. More, I have seen Donald Trump be elected president of the United States. I do not want to know what comes next as a result of this last condition. I was proud to serve in the navy of this great nation during one of the most silly and reckless of wars. I never really was in Korea. I couldn’t ever even see the shore of those people’s land. The pilots saw it well enough I suppose. But I saw the looks on the pilots’ faces and I guessed how much alcohol it took at the officer’s club to wash away memories and dark realizations.”

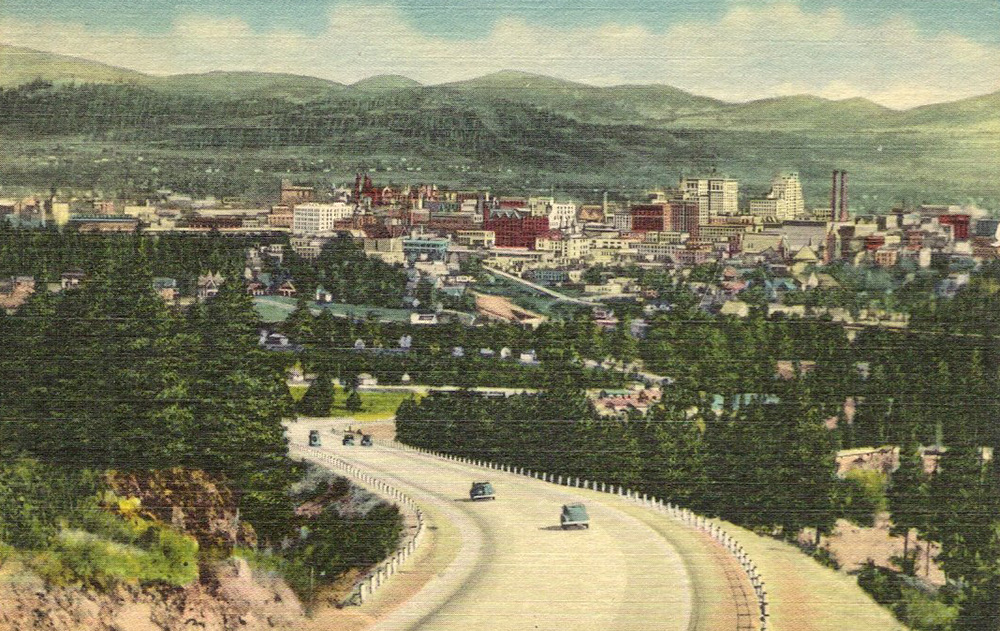

However, this story is not about what my dad did during the Korean War. It is about some things that happened after he was discharged from the San Diego naval base, and he and mom moved back to Spokane with one-year-old me. They bought a brand new 600-square-foot house in a working-class neighborhood. Dad, at that time, worked for a construction company that built our home, and because my father was a veteran he did not need to make a down payment.

As I grew up, I made a best friend in Tom Takasaki, whose family lived two doors down. We didn’t knock but came and went in and out of each other’s houses, especially in the summer when we were up to hijinks of all sorts, as boys are. I don’t remember not knowing the word Nisei. Tom and I took Nihongo language lessons together from Mrs. Matsumoto.

Sometimes, sometimes, I would be called into the Takasaki living room. It was some kind of sacred space with Catholic things on the very clean walls. “My dad wants to talk to you alone,” Tom would say. In that room one of those times, after I’d acquired my purple belt in Judo, Ray Takisaki congratulated me. For him, it was a hopeful sign that I might someday learn discipline.

Other times, Tom’s dad would tell me, as though it were some dangerous top-secret information, about how his family were rounded up like criminals and sent to a concentration camp in Idaho in 1942. They lost their business in Seattle, their homes. They never lost their humanity. These were for me powerful, sacred, restricted moments and I felt I was the vessel for something that no one in my city or world knew; something no one wanted to know about then and there.

One spring afternoon in the late 1960s, as Tom and I rode the Spokane city bus home from another day at Lewis and Clark High School, an evil thing happened.

Some teenager, a bully, I don’t remember his name (Tom might remember his name) said a sequence of words to Tom that ended in two words I knew only from war-movies and from ugly adult talk: “Dirty Jap!” I completely lost all sense of everything. I had no fear, but I did have hate. Yes, even now I remember the hate like a sour, foul taste in my mouth. I don’t remember the exact words but it might have been something like, “You fucking racist son of a bitch are getting off this bus right now and I will definitely beat your fucking brains out!” The bus driver promptly stopped the bus.

Tom and I jumped out. The bus took off in a rush and no one else got off.

Tom and I walked home in silence. When we got to his house, Tom merely said, “There’s no secret message in the White Album when you play it backwards. We tried it.”

Go back to 1956, when our family had just moved into our new house, the Second World War having ended just over a decade before. One slow day in the fall, when I was about four or five years old, a guy came to the door. This I know now. But I’d never heard this story until recently. It was never mentioned in my household.

Knock, knock. “We got a petition here and we want you to sign it Marker. There’s a Jap family that wants to buy that house two houses away from you. We don’t want their kind and we figure this petition will run em’ off.”

How do I know this happened? As I noted at the beginning of this prolonged parable, my dad died three years ago. We had a small memorial for him at my brother’s house in Olympia, Washington. There were cousins and aunties and uncles, his grandchildren, nephews and nieces. I knew, but didn’t know, how profoundly they all loved him. The food was good. Barbecue. Then he arrived. Tom. He’d driven six hours to show up. He said, “I have a story to tell.”

“My dad,” he said, “would only let us play with you kids. Do you know why? Well, when my family was trying to move into the neighbourhood, a bunch of people started a petition to keep us away. They came to your house and your dad told them to get the hell off his property before he lost his temper.”

My dad was a boxer in the Navy and was over six feet tall.

After that, back then, it was all pretty simple. Ray, Tom’s dad, became friends with my dad. They were what you might call very careful, respectful-from-a-distance-neighbour-type friends. Theirs was an old fashioned and beautiful kind of friendship. One day Ray said, “Bob, I will go house to house and get all our neighbors to sign on to be taxed to get our street paved. This dust is ridiculous.”

“Ray, I think I’d better go with you.”

Together they accomplished this and a number of other amazing things. I grew up watching this distinct friendship mature as they became old men together. When Tom showed up at the memorial I hadn’t seen him in about a decade. I do not know why he drove his little economy car all the way to my dad’s memorial alone to grab a microphone and say, “I have a story to tell about this man.”

Mom died in August. Their ashes are mingled together with the Selkirk Mountains that know no border between Canada and the United States. My mother, the progeny of Indigenous and homesteading people, had five generations of memories in the Salishan territory that was our homeland.

She married a navy mechanic with an eighth grade education from a poor German immigrant family. She married a man who refused to participate in racism. Their love for each other was deeper than the rivers and lakes of the landscape that was the stage for their human devotion concert.

I, their eldest son, have been left with their one great question, “How are we not one people?” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: