Bright, buzzing neon will light your way through the cavernous heart of Crystal Mall, a labyrinth of stalls that sell produce alongside specialties like fresh tofu and peppercorn pig ears.

Vendors will shout that their veggies are the cheapest. Shoppers, mostly older than you, will push and shove to secure a spot in one of many snaking lines. You’ll smell buns and bubble waffles, curry and charsiu — you might even glimpse a butcher wheeling a rack with a whole animal carcass.

It’s not in Chinatown, but a suburban mall.

It may be hard to believe that this very Chinese place can exist as part of Burnaby’s Metrotown. Its chaotic charisma is at odds with the polished vision sold by the neighbourhood’s condo ads.

Graham McGarva, who worked on Crystal Mall when he was at VIA Architecture, says its role is like that of an “appendix” — something anomalous or extraneous from the neighbourhood.

“Not a negative outlier,” he said, “but an outlier.”

People come from all over the region to shop at Metrotown, but their primary destination is the Metropolis supermall, British Columbia’s largest shopping centre. The Crystal is a five-minute walk away, but you can’t see it from the supermall.

Close readers of history will know that the Crystal Mall is more than just a quirky relic that lived on as a suburban downtown blossomed around it. It was a key part of growing that downtown — dreamed of and designed by creative authors who had just completed Concord Pacific Place, arguably still the most famous Vancouver development.

The story of the Crystal begins at the Dragon Inn.

It was a classic Chinese-Canadian restaurant with an all-you-can-eat buffet of dishes like egg foo yung and sweet-and-sour pork. The restaurant announced its presence at Kingsway and Willingdon with a giant vertical sign that featured a neon dragon and promised “SMORGASBORD” in large Charlie Chan letters.

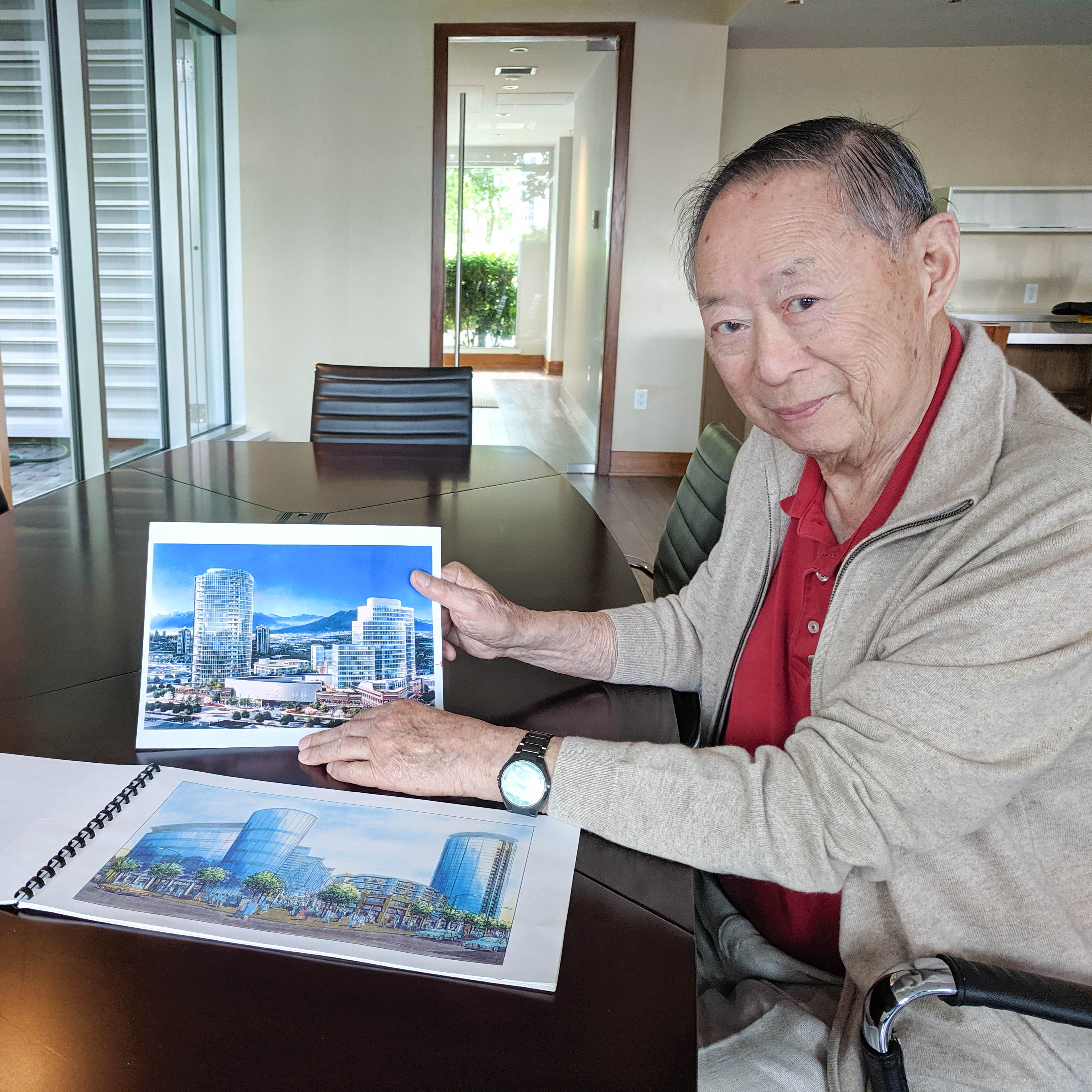

Sometime in the early 1990s, Larry Lee, whose family owned other Dragon Inns and Chinese Canadian restaurants, decided it was time to redevelop the site. A property manager Lee recruited, Edmund Francis Hyland of Hyland Turnkey Ltd., decided to bring onboard one of the biggest local names in real estate at the time: Stanley Kwok.

In 1988, Kwok — billed as an architect, planner and city builder — helped Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing win the bid for the Expo site on False Creek with an offer of $320 million. Kwok would go on to lead the planning and building of the $3-billion Concord Pacific Place.

“Afterwards, everybody wanted to work with me,” said Kwok. “But after I finished Concord, I didn’t know what to do with myself!”

It’s hard to imagine what the Metrotown neighbourhood was like then.

In the early 1990s there was no transit village, let alone a walkable community, despite the SkyTrain station. The Metropolis supermall, opened in 1986, was where the action was, and the car was king. Building near transit wasn’t the hot moneymaking recipe it is today. The neighbourhood’s demolition-and-displacement-fed densification would not happen for another two decades. And on Kingsway, retail suffered as the supermall sucked in shoppers.

“I thought it was quite a challenge,” said Kwok.

But Kwok loves tricky projects. He had heard two other developers had tried and failed to win the site.

“So I said, OK, I’ll take it on. I’ll see what I can do.”

Before coming up with a plan, Kwok looked at changes happening elsewhere in the region.

Vancouver’s Chinatown was suffering a classic case of inner-city decline — its proximity to the impoverished Downtown Eastside hurt its reputation — and Richmond was quickly evolving into a home for new East Asian immigrants. Hong Kong and Taiwanese investors had just started building Richmond’s first “Asian malls,” effectively indoor Chinatowns for the suburbs.

“Burnaby doesn’t have one of those,” thought Kwok. But he didn’t want to do a run-of-the-mill suburban mall.

Since Kwok had never done a project in Burnaby before, he decided to visit the planning department to hear what they wanted for the site.

The city planners had Metrotown’s future in mind. Their ideal was something pedestrian-friendly, and oriented towards the SkyTrain station. A hotel with conference space would be good too, as there wasn’t yet one in the growing neighbourhood.

“Fortunately, I knew the Hilton people,” said Kwok. “I went down to see them and they happened to want a hotel in Vancouver.”

With the Burnaby, Vancouver and Richmond forces in mind, Kwok went to the drawing board and came up with an unconventional plan that covered not only the block the Dragon Inn was on, but also the block beside it, to create a square.

At its centre, an East Asian-oriented mall in the shape of a circle was to be the ring that held a marriage of buildings together: an office tower, a hotel tower and a condo tower and low-rise buildings. This is the Crystal as it exists today.

“The visual imagery was of the Crystal resulting from an explosion of kinetic energy, with shards of building forms exploding out,” said McGarva, who was recruited by Kwok because they worked on Concord together. “I liked the forced intersection of these different worlds.”

To replace the street the Crystal erased, it would have a path cutting through the centre of the circular mall that allowed a way between the SkyTrain station and Kingsway. The hope was that it would help make car-oriented Metrotown more walkable.

The City of Burnaby was pleased with Kwok’s plan, with then-mayor Doug Drummond calling the Crystal “important” for Metrotown and the planning chief complimenting its “curving forms.” It would be a dense, cosmopolitan development for an urbanizing suburb.

The city also happened to own houses on his proposed superblock, and sold them to his team to help piece together the Crystal.

However, at the other end of the superblock on Kingsway, a deal could not be struck with three property owners, one of them A&B Sound, the popular B.C. music and electronics chain.

Kwok decided to forge ahead and ignore that corner. Those buildings are still there today, home to such businesses as Sleep Country and Love in Love Adult Store.

Two other partners joined Kwok, the local TYBA Group and a Korean construction company looking to get some Canadian experience called Dong Ah.

In 1996, the neon dragon at the Dragon Inn came down, and the formation of the Crystal began — over 750,000 square feet for a price tag of $200 million.

Kwok wanted to avoid criticisms of North American malls, which were being accused of killing local character and prioritizing chains over mom-and-pop businesses. He didn’t even want a major anchor tenant, just a big market and food court.

His solution was to reject the traditional mall model that saw businesses lease space from the owner and agree to rules on everything from hours to signage.

“Chinese like to own their own thing,” Kwok said.

So the units, from the shops to the offices, were stratified, meaning they were available for purchase. This required dizzying legal work.

It was unusual, as no mainstream mall in Metro Vancouver was made up of independently owned units and businesses. Merchants could sell what they wanted and add personal touches to their businesses. The inspiration was a Hong Kong street market.

“We were trying to do some anti-urban design where it was visually chaotic, with non-standardized signage,” said McGarva. “We thought it was good to have a dark public environment, with the brightness coming from the shops.”

The strata investors proved to be a great relief, because the Korean construction company Dong Ah was the Crystal’s largest investor, and the Asian financial crisis hit in 1997.

“People were locked into the investment,” said McGarva. “It couldn’t be over budget, so I had an overriding noose built in.”

But it worked. All the fragments of the Crystal — 269 shops, 218 condos, 68 offices, 283 hotel rooms and over 1,300 parking stalls — fell into place.

The Crystal officially opened in 2000, and McGarva recalled that it took a while for businesses to move in. Many of the investors preferred to rent out their units rather than launch enterprises themselves. But when they did, the mall was “totally quirky and unlike anything else.”

There were places to pick up a brand-name Japanese rice cooker, a zither lesson or a giant Gundam robot figurine, and a half-dozen places to get your laptop or cell phone repaired. Though some of the corridors away from the market can get eerily quiet.

A Christian organization took over a massive 13,000-square-foot space at the centre of the food court, and offers Bible studies and activities like martial arts, health social support groups and an art gallery for the public.

“For us, it was a miracle,” said Thomas Tam, the director of the Chinese Christian Mission of Canada, known as CCM.

The organization, now 40 years old, used to be located in a small storefront on Fraser Street.

“Our philosophy is to go where the people are,” he said. “When we heard about this space at the heart of Metrotown, right at the centre of Greater Vancouver, our board members started to explore the opportunity.”

They bought the space as one of the Crystal’s first owners, a smart decision considering how religious groups are struggling to find space today. The mission also plays the role of landlord, with three other churches renting their space at the Crystal for Sunday services.

The unconventional choice to have a wet market and food court as an anchor draw for the mall worked as Kwok intended.

For immigrant seniors who transit to the Crystal with personal shopping carts, the language and the products are a great comfort.

At the food court, visitors can choose from 28 mom-and-pop kitchens cooking up regional specialties like Shanghai xiaolongbao soup dumplings and Zunyi tofu pudding chili noodles for less than $10 a dish. Close your eyes and you might think the humid space, cooled by an arsenal of small rotating fans mounted on the ceiling, is a Singaporean hawker centre.

Some guests at the Hilton have no idea they share a building with such a thing as Crystal Mall, but there are also days when you’ll spot large groups of people taking a break from conferences feasting at the food court.

Workers wearing dangling key fobs from Metrotown’s office towers are also a common sight at lunchtime, eating carefully to avoid splashing soup on their shirts.

Sally Cai and her husband Pan run one of the stalls, Fung May, which serves Cantonese classics like congee, rice rolls and noodles.

The couple, who emigrated from Guangzhou in the early 1990s, live in Richmond and wake up at 5:30 a.m. to get to the Crystal by 6:30 a.m. to turn on the stove and start boiling the congee.

“The congee needs at least two hours,” said Cai in Cantonese.

“Any quicker and it’s not any good,” added Pan.

Cai, often sporting pink plastic sandals, handles the congee and cash, while Pan works the wok.

It’s a tight space to be handling hot food like boiling soups or prepping delicate items like wontons, especially at lunch time, but their stall, at 400 square feet, is already the largest in the food court, said Pan.

Behind the counter, every surface is spotless. It has to be, because it’s the only thing a shop owner can control in a shared mall.

“My heart jumps if I ever see a cockroach strolling in the food court,” she said. “Owners here lose sleep over them. Even if your stall is clean, what can you do if your neighbour’s isn’t?”

The relationships the couple have made in 10 years of putting in more than 13 hours a day to run Fung May speak to how the Crystal works. They get their veggies from a stall downstairs before the market opens. They remember the customers who make long drives from places like Maple Ridge or Port Coquitlam to visit the Crystal. When Pan hears a particular order at a certain time of day, he’ll know who the customer is; Pan may even tease them if they’re late.

Their children have also grown up in the business, sometimes helping out or doing homework at the mall — not at all uncommon for shop kids here. When Cai and Pan took over Fung May — the owner had decided to sell and retire after a severe burn on her leg — their daughter and son were 13 and six.

“You get to keep an eye on them, and they get to understand the kind of work that you do,” said Cai.

The Crystal has also grown, with more foot traffic, younger entrepreneurs and businesses more reflective of China as a whole, as the owners of Cantonese mainstays retire and pass their units on to newer immigrants giving the mall a try.

“It’s hard to find anyone to do this kind of Cantonese cooking anymore,” said Pan. “Young chefs can’t take the heat.”

He means that literally. It’s hot inside the stall. Pan estimates it can get up to 38 degrees Celsius. The physical work is tiring, and the hours are long. He’s trained staff before who’ve called it quits after three months.

The Crystal has also become a nerve centre for food couriers on delivery apps like Fantuan, who beeline in and out of the mall with Styrofoam towers of takeout.

Without a mall manager to set rules, the development has grown and changed organically — just as Kwok had hoped.

The Metropolis supermall has remained the heart of Metrotown, and it’s understandable why the Crystal lives in its shadow. A recently redeveloped mall, Station Square, is a physical obstacle between the two.

Many still view the Crystal as an appendix, a black sheep that doesn’t quite fit in, a hidden gem at best.

But consider what the Crystal means to all the people who pass through, the visitors who experience another culture and the immigrant diaspora who use it as a village market, and perhaps you’ll see that it is less of an appendix in the growing neighbourhood and more a heart of its own. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: