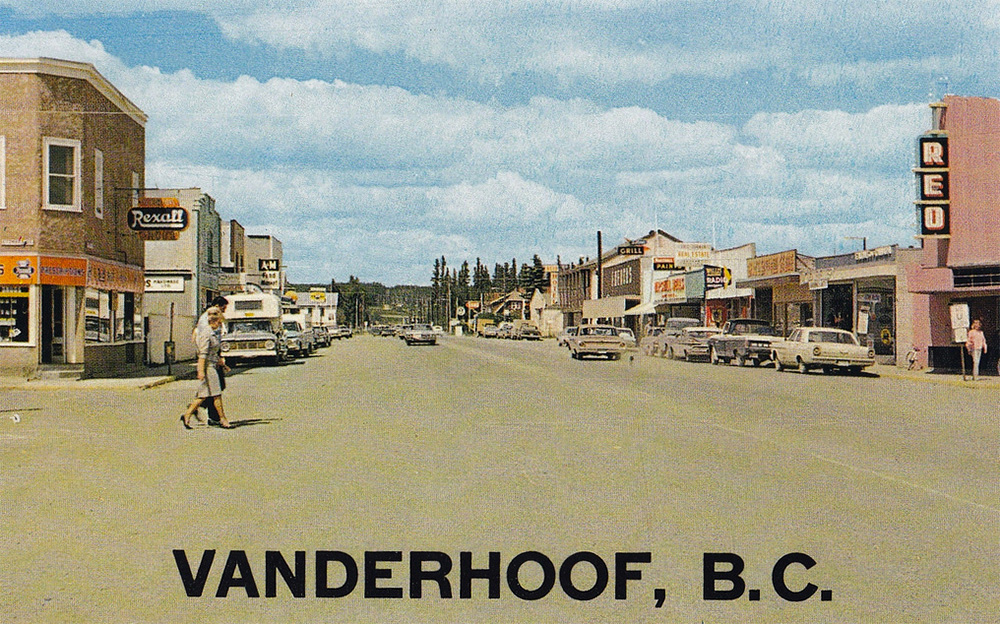

Poet and writing teacher Carla Funk is close to finishing a memoir of growing up in Vanderhoof in the 1980s, a fact The Tyee learned when we excerpted a small piece of the project last month as a selection from The Summer Book anthology. We were quite taken with Funk’s shimmering account of family life in a B.C. interior town that was, as she says, “full of logging trucks and God.” So taken that we circled back to Funk and asked if we could run more from her book in the making. She said yes, so today begins a three-part series of her snapshots from Vanderhoof, the proudly self-proclaimed “geographical centre of British Columbia.” You can read the first today here. And, to orient you a bit to the author and time and place she recalls, we offer this interview.

The Tyee: It’s a privilege to be able to preview for our readers some of your memoir of life in Vanderhoof. To orient us a bit, can you give a quick sketch of your family and why you lived there?

Carla Funk: “Both my mom and dad came from Mennonite families, but arrived in Vanderhoof via different routes. My Saskatchewan-born father, the firstborn of nine children, was a year old when he arrived in Vanderhoof in the early 1940s with his parents and grandparents on the first train full of Prairie Mennonites. My mother, one of eight kids born to American Mennonite-Amish parents, moved from Oregon to the Nechako Valley in the late 1950s when she was 10. As the story goes, my dad drove by in his logging truck and offered my mom a lift to school. A few years later, they wed, and my brother and I were born and raised in Vanderhoof among our many cousins, aunts and uncles, most of whom still live there.

“When we all get together on my mom’s side of the family, our count reaches well over 100, and includes a lot of home-baked pie, storytelling, theological banter, conspiracy theories, hollering toddlers and laughter.”

Now you live in Victoria, and were for a while the poet laureate there. What bit of Vanderhoof did you bring to that role in B.C.’s capital?

“Right after graduation, I moved to Victoria to attend university, and have lived here ever since. When I stepped into the role as the city’s poet laureate, I felt like an imposter. After all, I wasn’t a true Victorian — I was a small-town and blue-collar transplant, and I believed that good poetry can be both accessible and transcendent. I wanted to bring poetry to people who thought they wouldn’t ‘like’ or ‘get’ poetry, and to let them see the ordinary beauty of it, to show that poetry talked like they did, occupied the same world, and sometimes, beautifully, lifted them up out of it so they could see life from a new vantage.

“I still head back to my hometown at least once a year. My dad passed away a few years ago, but my mom still lives there — at least, for now, raising the chickens that end up in our freezer, growing the garden that we gratefully eat.”

Do you think Vanderhoof and other interior towns in B.C. are largely ignored by media coverage of the province? Are their people’s stories told enough? If so, what piece of the puzzle are we missing as a result?

“I’m not sure that people in small communities give a hoot whether the media pays enough attention to them. They have their lives, their work, and they faithfully go about it. Some folks in small towns seem to have a wariness of what my grandpa called ‘the high mucky-mucks’ — those in city centres of power who think they know best what the rural communities need.

“It strikes me that knowledge isn’t the same thing as experience, that bureaucracy often doesn’t understand the on-the-ground reality. But that’s the human problem, isn’t it? Until I kick off my ethically-sourced vegan sandals and walk a mile in another’s steel-toed boots, shed my organic suburban lifestyle to spend a winter in logging camp working night shifts in 30-below weather, my editorializing on the evils of the forestry industry might not have much clout.”

Your writing includes acute observations about gender — fathers and mothers, men and women, inhabit separate worlds, and roles, in many of the scenes you paint. Of course that was 30 years ago. Is that still true in places like Vanderhoof in ways distinct from, say, larger cities like Victoria and Vancouver?

“The traditional gender roles that played out in my childhood and adolescence are just that — traditional. They’re rooted in a long tradition whereby the men worked the fields and farm, and the women were CEOs of the household. Certainly, the Mennonite family structure favoured the wife and mother staying at home with the kids. Some of that came from a theology that put the husband as the primary provider. But a lot of that division of labour came out of practical wisdom.

“I bucked against that system in my adolescence, saw it as unjust, behind the times and annoyingly patriarchal. My dad, at the head of the dining table, used to hold up his empty cup and say, ‘Get me another glass of milk,’ and I’d fire back, ‘You have a piano tied to your rear end?’ I thought I was being a feminist. Turns out, I was just being a jerk. My dad grew up in a family where his mother waited meekly and faithfully on his father. He didn’t know any differently. And I didn’t know it was possible to be kind even when disagreeing with another person’s view of the world.

“Change takes a long time, especially in small interior towns and in the heart of a human, but it does happen. Case in point: my mother now has her own chainsaw, and I’ve discovered the sweet spot of practical feminism, which sometimes even finds delight in making my husband breakfast before he heads off to work.”

There is also a recurring theme in your memoir of religion — Vanderhoof’s Mennonite and Catholic communities for example. Can you tell a bit about where on the religious map your family fit in then, and where you are now? I’m curious, for example, how your family’s religious lens interpreted all the nature that surrounded you, and the way it also produced work, and wealth, for the community.

“When I was about six or seven, the travelling illusionist Reveen was scheduled to perform a show in Vanderhoof. Several of the churches banded together in public outcry, proclaiming his mind-bending tactics and magic to be evil, kin to witchcraft. They held a big meeting, at which they prayed fervently against Reveen. The show did go on, but the morning after the performance, in a chapel assembly at the church-school I attended, the principal reported that none of Reveen’s hypnosis had worked on the audience members. When he tried to hypnotize a man into clucking like a chicken, the fellow just laughed, and the audience booed. Reveen vowed never to return to Vanderhoof for another show. ‘Praise the Lord,’ said the minister, and we all clapped and cheered. That’ll teach Reveen, I thought, never to mess with our God.

“I grew up on black and white, darkness and light, this side or that side. At one point, Vanderhoof boasted the most churches per capita in all of Canada. That gives you an idea of the religious landscape of the town. My mother’s family attended a charismatic Mennonite church, which meant they believed in the gifts of the Holy Spirit but still didn’t think women should wear jewelry, makeup or jeans. My dad’s family belonged to a different Menonnite church — one that was quieter in its expression of faith, and more relaxed in its theology of cosmetics. But no matter their theological differences, these saints and sinners understood what it meant to live as a community, unified in purpose and in values, stewarding their shared and common ground. Love your neighbour as yourself — that verse rang out in word and deed, from the meals dropped off at the home of a new widower to the communal work in the butchering shed, every family taking home a portion of the lard, the sausage, the headcheese and the hams.

“As a searching, cranky teenager, I shucked it all off — or tried to, anyways. But our way of looking at the world as a broken Earth that was tilting toward redemption never left me. How could I lie in a field of snow on a clear-skied January night and not wonder at the stars, and how they got there, and who was behind all the beauty. In my twenties, I found myself drawn back into the mystery of faith, but it took years for me to feel like the religion I grew up with had become real and vibrant and personal. Now, I’m all in. There’s so much about God I don’t understand, so much doubt and mystery, but that’s faith. I’ve never met anyone as compelling as Jesus. No one has ever told me a better story or shown me more hope.”

What do poets notice, how do poets think, that’s different from, say, journalists or political advocates?

“Instead of the perfect lede, the killer quote, the commentary on the statistical analysis of the latest figures on the current research on today’s most pressing issues, I’ll go after the hard, clear image, and geek out over the metaphor that illuminates the truth beyond the facts.”

Anything else you’d like to share?

“In case it’s not clear, I adore Vanderhoof. That town has given me a bounty in experience, imagery, lore and love. If you haven’t visited that geographical centre of the province, of the universe — go. The river that cuts through the Nechako Valley is a beauty, in summer and in winter. The people are real and full of stories. And Woody’s Bakery makes a mean apple fritter.”

Read the first of three pieces from Carla Funk’s (as yet untitled) memoir, here. ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: