[Editor’s note: This Labour Day week The Tyee is daily publishing excerpts from Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle, a new comics-style collection of stirring moments in Canadian labour history. Today’s offering is from the chapter “Coal Mountain,” written and drawn by Nicole Marie Burton.

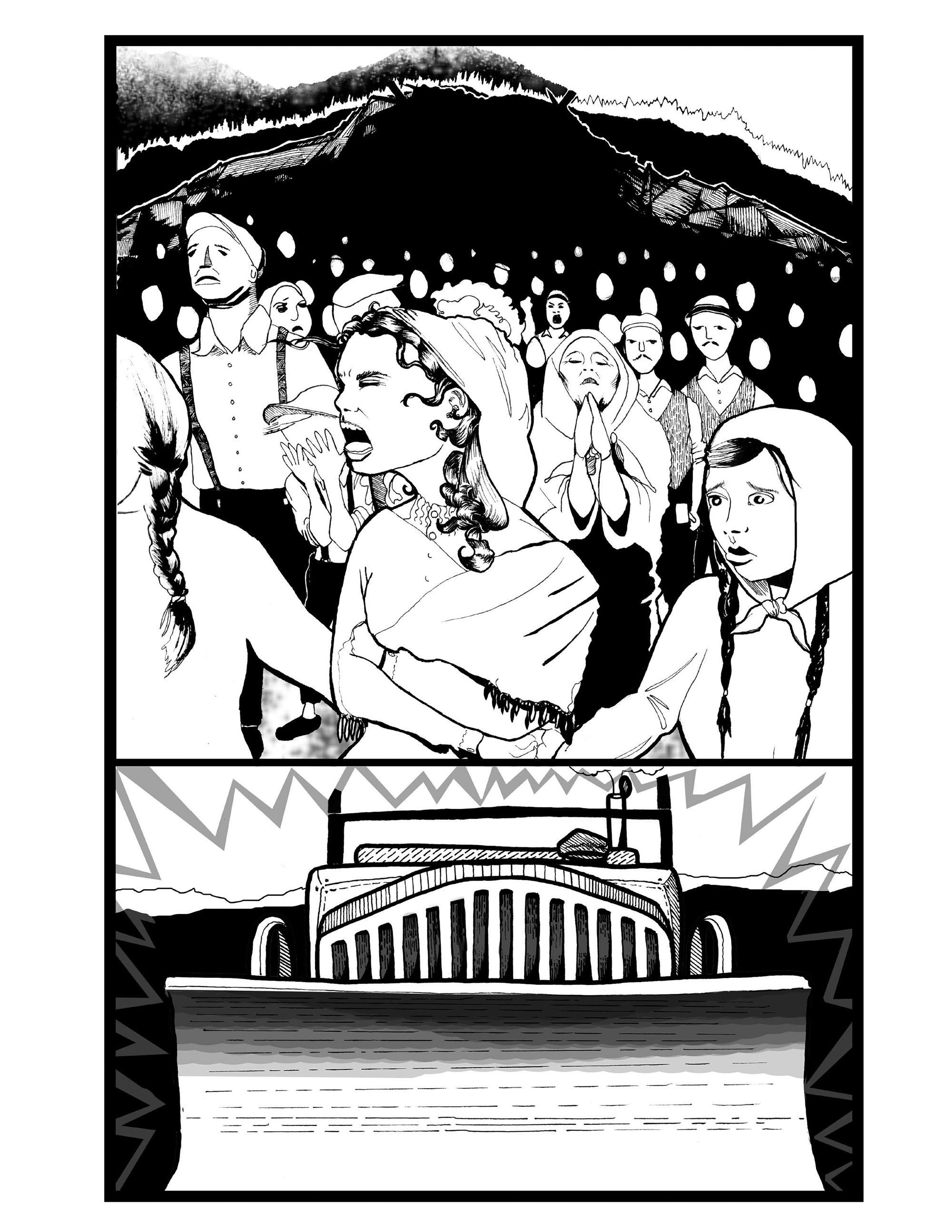

In the little, now faded, company town of Corbin near Crowsnest Pass in eastern B.C., coal miners struck for better wages and working conditions during the harsh winter of 1935. The owners refused to yield, eventually bringing in “scab” replacement workers to break the strike. On April 17, when the miners massed to protest, their wives formed the front line of the demonstration. They found themselves facing the broad, sharp blade of a snowplow fronting baton-wielding police. The plow lurched forward, police began beating the women with their riot sticks, and the striking men responded in fury. What ensued, by one account, “wrote a page of unparalleled police brutality in Canadian history.”

Nicole Marie Barton’s graphic history of those times in Corbin is told through the eyes of child named Gracie, based on the recollections of Grace Roe, who spent some of her childhood in the mining town and bore witness to the hard life and tragic events there. The page excerpted here sets the scene.

For more context, farther down, read Simon Fraser University labour historian and trade unionist Ron Verzuh’s essay “Holding the Line in Corbin”. The work of Burton and Verzuh is excerpted with permission by Toronto-based publisher Between the Lines.]

HOLDING THE LINE IN CORBIN

Essay by Ron Verzuh

In Coal Mountain: The 1935 Corbin Miners’ Strike, artist and author Nicole Marie Burton proves that Canada’s labour history is anything but boring. By bringing to life an incident in British Columbia’s past that has been obscured for too long, Burton takes a sympathetic yet conscientious approach to her task, one that historian Bryan D. Palmer has described as enabling the labour and social historian to “glimpse the tenacity of common people struggling against increasingly harsh realities.”

In that spirit of deep understanding and in stunning detail, Burton tells the story of Corbin, a company town built in the early 1900s by Daniel Chase Corbin of Spokane, Washington, a prospector, railway builder, and founder of the Corbin Coal and Coke Company. As Burton shows with her powerful images and terse narrative, the people of Corbin had big hearts in the 1930s and they needed them to cope with the poor living and working conditions that Corbin offered its workers.

In another innovative approach to recounting labour history, Burton chooses as her narrator a young girl named Gracie to relate descriptions of those conditions. Based partly on the recollections of Grace Roe, a woman who once lived in Corbin, this literary device adds an intimacy to the Corbin story. Drawing on interviews with Grace Roe, Burton looks at history through “a different set of eyes,” offering us Gracie’s view of the tragic events that led to one of the Canadian mining industry’s most brutal attempts to break a strike.

With her stark images of the lives of the miners and their families living in the Crowsnest Pass area of British Columbia, Burton transforms an important event in Canada’s labour history into a moving visual documentary, making it come alive with pictures and text. In her memoir Right Hand Left Hand, celebrated Canadian poet Dorothy Livesay also vividly recounts what happened. To illustrate the scene, she quotes one of the strike leaders: “The womenfolk were grouped in the middle and some were up front. Suddenly, as at a signal, the full detachment of police ran out from the hotel and grouped themselves in two squads on either side of the caterpillar, flanking the picket line....Before we could understand anything the caterpillar was moving forward, straight at our women.”

Seventy-five years later, in 2010, a report in the People’s Voice reminded readers that “the legs of several women were crushed, and one woman was dragged 300 feet by the bulldozer. Another had to be hospitalized after the machine’s blade tore the flesh from her legs. A pregnant woman lost her unborn child after being clubbed across the shoulders and her abdomen.”

As Burton explains, 50 people were hurt, including 14 police officers, and 17 strikers were arrested, but the mine in Corbin stayed closed. The struggle continued for many months and the company’s unconscionable behavior was broadly exposed by labour-friendly politicians like Tom Uphill.

Historian Allen Seager notes that the events at Corbin had “an electric effect” in Blairmore, Alberta, where militant members of the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada (MWUC) adopted the radical outlook of the Communist-sponsored Workers’ Unity League (WUL). Disgusted with the violent way the Corbin company had responded to the strikers, the MWUC sent money and other forms of support to strikers and their families.

MWUC leaders also led a march uphill for 16 kilometres to reach the town, singing the great labour anthems of the day, including “The Red Flag,” “The Internationale,” and Joe Hill’s “The Preacher and the Slave.” What they saw when they arrived in the strike-torn and defeated camp was a town that one strike leader described as struck by “police terror.”

The WUL’s Harvey Murphy, who organized the march, described the aftermath: “The doctor was out of medicine, and all kinds of people were hurt...There was just this narrow roadway and the police had this wired. That’s why the doctor was out of medicine for these injured women. They were locked in, and the R.C.M.P. was in charge…. And it was only when we got through that we got those people out of their houses.” Secret police reports record the efforts of Murphy and other MWUC leaders to rally the unemployed and miners in Southern Alberta to support the Corbin strikers as they would do for many strikes in the mines and metal smelters of B.C. and Alberta. But despite these attempts, the miners of Coal Mountain eventually moved away to look for work elsewhere.

Valour and determination

The company town of Corbin, once boasting a population of 600 souls, was abandoned in the early 1950s and became an almost forgotten ghost town. Some traditional historians might consider the Corbin coal strike a failure. After all, in its assessment of the dispute, the Labour Gazette of June 1935 concluded that “a number of strikers were charged with assault, creating a disturbance on a public highway, and impeding police in the discharge of duty.” It further reported that “nine were sentenced to terms in jail of three and six months and 13 were fined. Appeals from the jail sentences were entered in some cases and the convicted men released on bail.”

Others might assess the outcome of the bitter strike in less clinical terms, perhaps seeing what Burton sees: a struggle deserving of our attention because it points to the valour and determination of men and women who were willing to hold the line in their fight for the right to earn a decent living, to not back down.

Historian Irene Howard numbered the Corbin women among “militant participants in labour struggles” in B.C. In her account of the activities of the Mothers’ Council of Vancouver, she saw them as akin to the Chartist women in the Great Britain of the 1830s, or the women of the Paris Commune of 1871, or the “revolutionary sisters” of the famed Bread and Roses strike of textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912. One could easily add the monumental women’s victory in the early 1950s during a violent New Mexico miners’ strike as depicted in the banned film Salt of the Earth.

Like these and other powerful historical occurrences, the Corbin strike should be recognized and celebrated rather than, as Howard remarks, “omitted from ‘official’ history.” Instead of being jettisoned as insignificant, that story deserves to be told, and what better lens through which to view it than Gracie’s eyes?

Now with Coal Mountain we can do precisely that. By revisiting the tragic events of 1935 through Burton’s depiction of the lives of the Corbin miners and their families, we can take a graphic tour of their struggle and witness the courageous actions of the men and women of this company town eighty years ago. Thanks to Burton, Corbin takes its proper place in labour history as a symbol of resistance to oppressive employers everywhere. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: