In 1957 a group of anthropologists from museums in Vancouver and Victoria, a filmmaker, a Haida crew and the renowned artist Bill Reid, then a CBC broadcaster, set out to "save" what were considered to be the last remnants of an endangered culture. Armed with saws, a small boat and a carpenter to hammer together the shipping crates, the team arrived on Anthony Island off the far southwestern coast of Haida Gwaii that summer.

"We weren't too late. Everywhere there was a wealth of wonderful detail, powerful wings and feathers, huge impassive eyes, little crouching figures. The jungle growth of the North Pacific had almost reclaimed some of the poles, crawling over them and splitting them with its roots," said Reid in his narration of a CBC television documentary.

As the monuments were gently lowered to the ground, each member of the group may have wondered whether they were doing right or wrong. After all, the standing poles honoured the chiefs, clans and carvers of a once mighty village. Many had died of small pox or other diseases, and in the mid-1800s those who were left moved to Skidegate. Tragic circumstances had left the village, known as SGang Gwaay or Red Cod Village, to the ghosts.

Was taking the poles an act of desecration or a way to save great works of art from annihilation?

It's an age-old question and the crucial dilemma explored in Beyond Eden, a Theatre Calgary/Vancouver Playhouse co-production written by composer and playwright Bruce Ruddell. The musical opens tomorrow, Saturday Jan. 16, during the Vancouver 2010 Cultural Olympiad.

Reid's life-changing voyage

Ruddell became intrigued by the story through his friendship with the iconic artist, Reid. In 1957 Reid was a radioman, aware of his Haida heritage but only beginning to embrace it. So, when given the opportunity to join anthropologists Wilson Duff, Michael Kew and Harry Hawthorn on a trip to the remote ancient villages of his ancestors he jumped at the chance. Ruddell says the trip (and a similar 1954 reclamation project at the villages of Tanu and Skedans) dramatically changed the lives of at least two members of the expedition -- Reid and Duff -- and it's these two men who became key characters in his fictionalized play.

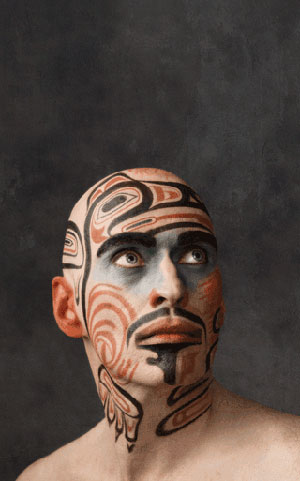

The primary character is anthropologist Lewis Wilson, played by former Spirit of the West lead singer John Mann. Wilson, based on Duff, is the expedition leader, and he becomes haunted by ancient Haida voices questioning the morality of his life's dream -- to rescue these poles and bring them to safety and increased visibility in an urban museum.

Duff was a curator of anthropology at the provincial museum in Victoria from 1950 to 1965 and later joined the faculty at the University of British Columbia. He was passionate about northwest coast art and his discoveries inspired many anthropologists to see deeper meaning in the images carved in stone, wood, antler or bone. Well-respected by people up and down the coast, he was also an expert witness for the Nisga'a land claims case, wrote extensively of the impact of the white man on aboriginal people and led several other pole removal expeditions in other areas.

Haida Gwaii Museum director Nathalie Macfarlane moved from Ontario to Vancouver in the mid 1970s because she wanted to learn from him. She had read his seminal work, Images: Stone: B.C., which delved into the symbolic rather than just functional aspect of a group of prehistoric stone carvings.

"It was quite radical at the time to present pieces as artworks as opposed to mere functional representations," she says.

He was also a very popular lecturer, and his third year anthropology course at UBC was always packed. "He was known to come to the lecture theatre and say, 'Professor Wilson Duff isn’t here today, but Charles Edenshaw [considered one of the great Haida masters of the 19th century] will take his place.' He would then speak to the students as if he were Charles Edenshaw," she says.

'See how deep this cut'

In 1976 Macfarlane started a job at the UBC museum and he was to be her supervisor. But Duff, who after the expedition, had never gone back to Haida Gwaii, committed suicide that summer. It is the arc of Duff's passion, quest and death that Ruddell has sped up and fictionalized in his play.

Max, the carver, (based on Reid who quit his CBC job to focus on art soon after the trip and played by Cameron MacDuffee) is haunted by the ancestors' voices too, but this is overshadowed by his desire to have poles brought to the city where they will be close to him, so he can learn to carve.

"See how deep this cut, how the plane runs vertically. See how deep this cut, how the form arcs beautifully... Teaching these hands to see...," he sings in one of the many original songs Ruddell has composed for the work.

Theatre Calgary director Dennis Garnhum says the musical, which also stars aboriginal actor, Tom Jackson (as the Watchman), is mostly told from the white man's perspective. "It’s a different community looking at a story from a different vantage point. Our unique challenge is finding the spirit of the truth," he says.

Two Haida women, Raven Ann Potschka and Erika Stocker of Massett, will make their professional theatre debut as ancestors whose singing haunts the team. The two started rehearsals in Calgary on Dec. 17 and although they've both been involved in local productions before (a locally-written Haida language play, Sinxii’gangu or Sounding Gambling Sticks had a short but successful run in 2008), they've enjoyed the opportunity to work with such a high-calibre cast and crew. Potschka says the move to Vancouver, where the show opens on Jan. 21, is an important one for the cast, many who are First Nations from across Canada. They are looking forward to going to the Museum of Anthropology to see the actual poles that were cut down so many years ago. "It will deepen the experience for everyone," she says.

"It's an important story in Canadian history. They thought we were a dying culture and wanted to preserve the art. But we are still alive and thriving!" she says.

'The eternal debate'

Garnham admits he fell into the same trap of wanting to rescue the poles still left at SGang Gwaay when he and his production team toured the islands last spring, reinforcing the clash between the European need to preserve things and Haida decision to let the poles return to the earth.

"The eternal debate is should they be left to rot, or should we preserve them so more people can learn about them. Seeing what's left. It’s sad. But beautiful..." he says.

It's still a sensitive topic on Haida Gwaii today. Roy Jones Sr. of Skidegate was a young fisherman when Duff hired him and his two brothers to take the 1957 team to Anthony Island on his 54-foot seiner. He remembers the trip well. He and his brothers, Clarence and Frank, helped set up the camp, rig up the lines, and make the actual cuts that brought poles -- as much as 50-feet in height -- down. Jones, who is the only team member still alive, says he walked up one of the poles like a logger walks up a spar pole to get a line around the top. "[Loggers] have spikes, though. I had gumboots and a rope around my waist."

Now in his mid-80s, he is reflective about the experience, having enjoyed the physical work and the company of members of the crew -- but about cutting the poles? "It didn't feel right," he said. However, the Skidegate Band Council had approved the work and many felt it was the right thing to do. Further to that, Jones was on a recent trip to The Chicago Field Museum and saw one of the poles taken from Skedans (an expedition he was also on). "If they hadn't taken it at that time, it would have been ruined, I think," he said.

The sacred element

Barb Wilson, the cultural resource manager responsible for Haida heritage sites in the southern half of Haida Gwaii (now Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site), agrees that the remaining poles are slowly disintegrating, "Much to the visitors' distress."

In the old days, memorial poles, raised to honour chiefs, would have been taken down when they became a hazard and then clan members of high standing would replace them. "It was quite an honour to be given a piece of a pole at a potlatch," she says. But because so many of the villagers were decimated by small pox, customary practices fell by the wayside. A new approach had to be found.

"In 1995 we took all the chiefs that were alive then and talked about what could or couldn't be done," she said. The chiefs decided that because the poles left were mortuary poles and it was the scene of so many deaths, that the area should be treated like a cemetery. After one effort was made to raise those poles that were leaning and/or on the ground, the only conservation parks staff are allowed to do now is to clip new plant growth from the tops or the faces of the poles.

Replacing poles has been discussed, but the money is not within reach and then a new question must be asked: "Would the site have the essence that people go there for?" she asks.

Stocker, who at 19 sees her involvement in Beyond Eden as her first opportunity to step beyond her home on Haida Gwaii, says the play offers many ways to think about these issues. At one point a character talks about how people have stepped off the path and forgotten the sacredness that is behind their art. She thinks the play can reach a wide audience by bringing these universal themes alive. "It's happened to people all over the world," she says.

Beyond Eden plays in Vancouver Jan. 16 to Feb. 6 at the Vancouver Playhouse. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: