[Editor’s note: Under the White Gaze originally ran as an exclusive Tyee email newsletter last fall. We’re republishing the full series of essays on our site this month. This essay, the seventh in the series, was originally titled 'White at the Museum.']

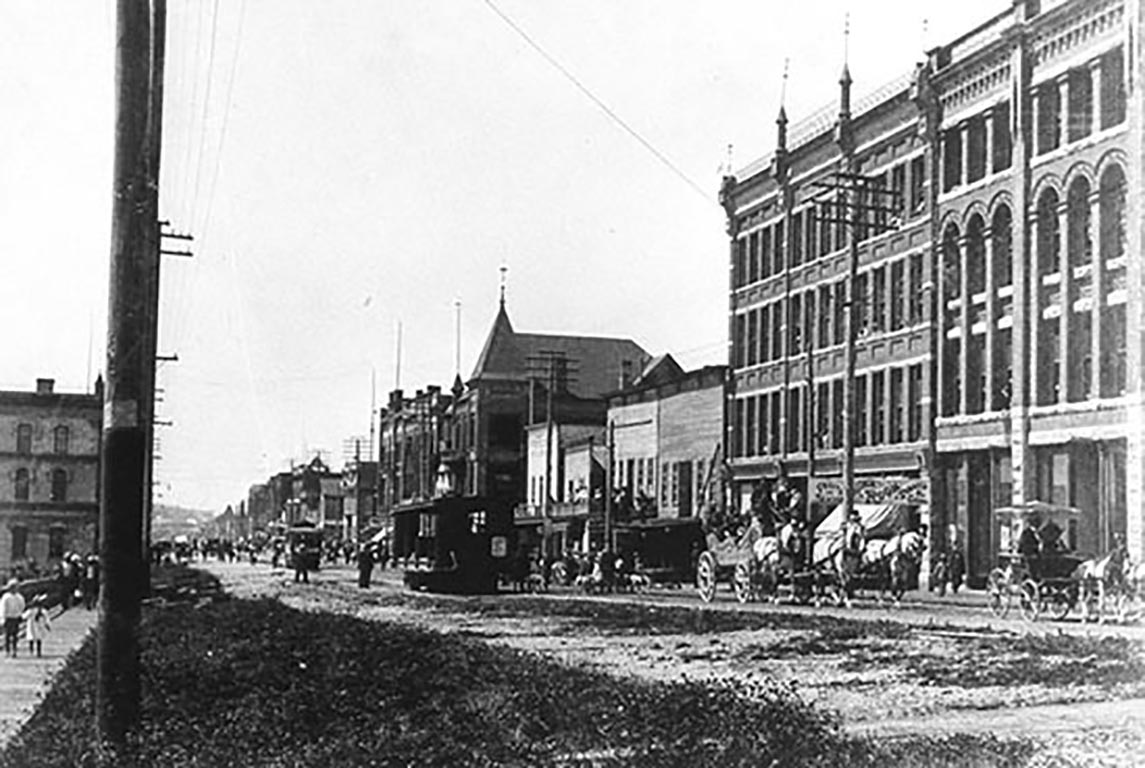

We’re going on another field trip today — New Westminster, B.C.!

If you strolled into the city’s museum a decade ago, it would’ve been all about the British colonial narrative.

The city was the original capital of the colony of British Columbia, and the museum showcased exhibits on everything from Victorian fashions to the Queen’s visit in 1971.

In 2011, a member of the city’s multicultural advisory committee told the museum’s curator that people of colour did not see themselves reflected in the institution.

Another person who visited the city’s Irving House — built in 1865, the oldest colonial house still intact in B.C. — told the curator that nothing about the heritage site would make her visit again.

The house wasn’t entirely devoid of racial representation: inside was the print of a Black man kneeling before Queen Victoria.

What’s a museum to do? The ones steeped in colonialism don’t have good track records when it comes to inclusion.

“Historically, museums were presented almost as a political statement to assert someone’s dominance in an area and demonstrate longevity,” explains Robert McCullough, who manages the museum and heritage services at New Westminster.

What happens when marginalized voices aren’t reflected in community records?

We’re six essays in, so you’ll already know some of the outcomes when ethnocultural groups are stereotyped or left out of journalism.

We’ve talked about how coverage frames migrants as good or bad; how coverage ignores or belittles racialized neighbourhoods; and how coverage pins behaviour on race, while neglecting inequalities of gender, class, etc.

But we’re not just lacking stories that show the diverse reality of our present. We’re also lacking stories that show the diverse reality of our past.

That’s why we’re visiting a museum today — to have a longitudinal look at how the white gaze has silenced racialized people in some of our community records.

The gaps in museum archives have a lot of lessons for journalists on how we chronicle the times.

Who are the people we are leaving voiceless? How does their absence shape how we understand our communities? How do we decide which stories are considered “important”? How do we make space for people who’ve been previously neglected to share their stories and views?

In 2017, New Westminster’s council approved a new mandate, long in the making, to decolonize the museum.

One of the goals was to “enhance knowledge and deepen understanding of the city and its diverse peoples — from the First Nations cultures to the multicultural community of today.”

But when New Westminster Museum curator Oana Capota and her team started digging through newspapers to collect stories, she found that “people of colour were always criminalized.”

There were stories of them getting drunk, stealing hats, forging cheques and committing “ridiculous offenses.”

“I’d find something like a Japanese man I’ve been researching arrested for riding his bike in the wrong direction,” Capota says.

I’ve noticed the same dehumanization and vilification when reading stories about people of colour in BC’s history.

Disasters were often turned into spectacle. In 1909, the Columbian newspaper covered a Burnaby train wreck, describing in detail the gore of peeled scalps and severed heads of the 23 Japanese men who died, but including none of their names — only that of a white survivor named George.

Even something like health was blamed on race. In 1917, the Vancouver Daily World blamed the spread of the Spanish flu among “Red Men” for “declin[ing] to take proper precautions,” and among the “Oriental population” for their “wages of sin.”

To update its collection, the New Westminster Museum worked with such newspaper records, but also turned to the public to surface 'new' stories that haven’t been told in a formal way.

“I think white Anglo-Saxon people are used to being in museums, and so will often approach me and say, ‘Here’s something I know the value of, and it should be in a museum,’” Capota told me.

“Other groups, they haven’t seen themselves in a museum, so they wouldn’t think of approaching us.”

The concept of value stuck with me.

Other journalists and I have had similar experiences. Almost everyone who contacts me out of the blue with a story idea that they “know the value of” is white. But for stories centred on the experiences of people of colour, particularly migrants, I have to go find them.

But when I talk to them, some have refused to do interviews, saying things like: “I’m not an expert.” “I’m not interesting.” “I’m not very good at speaking.”

It’s not that they lack personal self-worth; they’re not used to seeing themselves in a formal record of their community. And if journalists or other chroniclers don’t proactively seek out these stories, they may never be recorded.

There’s another common pitfall of representation in Canadian history: 'Communities of colour are only allowed to share one story.'

That’s something Naveen Girn, one of the museum’s guest curators, told me.

For South Asian Canadians, it’s the Komagata Maru. For Chinese Canadians, it’s the head tax story. For Japanese Canadians, it’s the internment.

Girn remembers his high school class in Vancouver zipping through these stories in a week, as if paying diversity dues.

These stories are, of course, hugely important events with lasting historical effects, key flashpoints of people of colour fighting discriminatory governments.

But if they’re told in the same way, their overemphasis in media and historical accounts can lead to blind spots.

They may be used as shorthand for an entire race’s experience. They may sideline other stories of Canadians of colour. They may silo “diverse” history as different from Canadian history. They may give the appearance that systemic discrimination is relegated to the past.

I did a quick search in the Canadian Newsstream database of stories from major newspapers to examine the scale of this. In the past decade, 62 per cent of the 3,600 stories that mentioned “Japanese Canadians” also mentioned “internment.”

The challenge today, says Girn, is to open up the “scope of stories.”

Communities of colour have more than one storyline.

In the end, a collaborative approach with the public enriched the New Westminster Museum’s record of the city’s history.

The museum looked everywhere from city committees to knitting groups to powwow workshops and beyond.

They wrote family profiles for incoming donations of artifacts and conducted oral history interviews. Thanks to these, new light was shone on the city’s Sikh, Chinese and Black heritage.

The efforts revealed New Westminster, despite its British roots, to be a very diverse place.

The first Japanese person in Canada lived in New Westminster. The earliest property purchase in the archives was by Black residents in 1860.

There were two Chinatowns. Queensborough, on the other side of the Fraser River, was home to a Sikh community, many of whom worked in the lumber industry.

And of course, the city is on land that was originally home to the Kwantlen people.

One museum exhibit, “Hair Apparent,” included a story from 1859 of one of the city’s first barbers, who was Black, and used a barrel for a chair.

Another was “An Ocean of Peace,” which traced a century of Sikh history in New Westminster, told through intimate objects like photo albums and weaponry on loan from families.

Stories included the founding of a gurdwara in Queensborough and the life of the anti-imperialist revolutionary Mewa Singh, who was executed by hanging in the city in 1915.

Seeing is often believing when it comes to representation.

How would anyone understand a community if the diversity of its history and residents is not visibly reflected?

And how would racialized people feel they have a voice in the community if they’ve been neglected from the official record for so long?

Personally, I’ve often second-guessed whether stories outside of the white gaze were worth writing about, because I haven’t read about them before — whether it’s some cultural food or practice or special place.

When I write about these things, some readers ask why I’m wasting my time and not covering the “bigger issues” of the day.

I suppose when a lack of diversity is normalized, a glimpse of diversity almost seems abnormal.

Capota at the museum has a response to this.

Spotlighting diversity doesn’t over-privilege it, she says. Rather, it brings to light experiences that “have been hidden.”

Discussion questions

- What’s a story you learned that changed how you view a place?

- How can journalists and other community chroniclers do a better job of making sure the diversity in their communities is recorded?

Readers’ corner

From a writer of high school textbooks:

“A few years ago I was asked by a publisher to write a social studies textbook to accompany the new B.C. curriculum. I originally declined the offer, as I said I hated textbooks because they don’t tell the stories that need to be told, and they all tend to be so Eurocentric.

“The publisher eventually convinced me that this would have a global perspective and really prompt students to think more and engage with wider perspectives (certainly a goal of the new social studies curriculum).

“I ended up writing the textbook, but ended up still frustrated by all the stories, voices and perspectives that ended up on the editing room floor.... So many teachers don’t know the stories (and don’t know where to look for further stories), aren’t comfortable talking about things they aren’t expert in (which makes them shy away from being allies even if they have good intentions) or are simply trying to be allies, but end up paying ‘diversity dues’ and zipping through stories and then onto the next era or event. Many are doing amazing work; it gets better and better each year. But we still have a ways to go.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: