One possible response to Vancouver’s housing crisis that has been largely overlooked is a strategy called vacancy control. It was once the law of the land. We should take a hard look at bringing it back.

Vacancy control extends the prohibition against excessive rent increases beyond current renters to include the unit itself.

Right now, the B.C. Residential Tenancy Act allows landlords to increase rents without limits when a unit becomes vacant. Lately those increases have often exceeded 25 per cent. This is a problem for a few reasons.

It gives landlords incentives to force out long-term tenants, many of whom are lower income, through a process called “renoviction,” because evictions are legal if renovations are substantial.

And it gradually degrades the availability of affordable housing units as the normal churn of vacancies of this housing stock pushes prices further and further out of reach for service workers with median household income and below.

Without vacancy control we are likely to see a continuation of raging land price inflation as buildings are increasingly acquired and renovated by real estate investment trusts, or REITs, and other real estate investment corporations. The trend is fuelled by global investment capital seeking annual returns of greater than 10 per cent.

It wasn't always this way. Vacancy control was a key part of the BC NDP 1974 initial law. It was struck from the act in 1984 when the Socreds retook power.

What the critics say

Some argue that vacancy control harms existing landlords. That depends on your definition of hurt and what kinds of landlords you seek to protect. Vacancy control would reduce the attractiveness of our rental properties to REITs, leaving more of that stock in local hands. Why? Because when a REIT does a financial gains assessment on an existing building, absent vacancy control they can and do assume that they will get "market rents" from the building. Not right away, perhaps, but as soon as existing residents can be legally evicted so new management can boost prices to market levels.

To the uninitiated this may not seem tragic, until you place yourself in the shoes of a person paying below market rent because they have yet to be renovicted. So many people are in that situation that the difference in rents between the existing median rent and market rents for a one bedroom apartment can be double. In a neighbourhood like Kitsilano, for example, where according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. median rents are $1,139 per month for a one bedroom, "market" rents are around $2,500 per month, or in some cases much higher.

This difference between median and market rents has never been this wide and is entirely a function of how well rent control, under the existing law, has protected renters and, to some extent, kept a lid on the hyperinflation of urban land values we are currently experiencing.

But this potential and actual difference explains why REITs are in town offering spectacular prices, based not on median rents but on doubly high market rents.

The return of vacancy control would eventually be reflected in less rapid inflation of the market price for existing rental buildings (and the land below them) and would incentivize current owners to hold and maintain existing properties for long-term equity gain versus immediate big paydays.

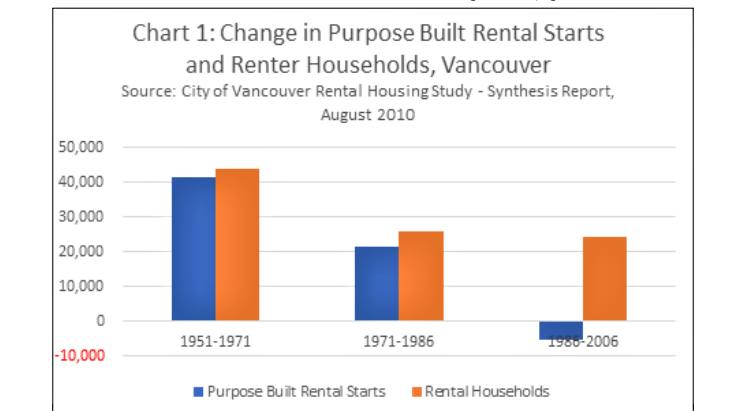

Critics, including landlord associations, also claim vacancy control will halt construction of purpose-built rentals. But a more careful analysis suggests not. It was landlords who convinced the Socred government to do away with vacancy control in the 1980s, arguing that measure stood in the way of new investment in rental buildings. But if that was their hope it didn't work out. Rental building construction fell off a cliff in the 1980s, not recovering in Vancouver until the 2000s when tax incentives favouring rental buildings over condo construction were instituted.

Studies have shown that in Manitoba, where vacancy control has been the law for decades, no noticeable slowdown in rental building construction has been noted as a result.

Taming the rise of land values

So while it’s not clear what will or won’t get built under a vacancy control regimen, one result is almost certain. Vacancy control will put the reins on the 200 and 300 per cent increases in the price of rental-appropriate land parcels that are making Vancouver ever less affordable.

That is because if builders can’t expect to demand higher rents over time, they will insist on paying less for land to meet their penciled out profits. Land markets will eventually adjust to changed market contexts.

Will that cause rentals to be an increasingly small proportion of Vancouver’s housing mix? Not necessarily, if the city and province use other incentives at their disposal to encourage the building of affordable rentals. It's worth mentioning that even our existing weaker rent control also has had a downward influence on land value and yet since the 1970s the proportion of rental units available in our city has stayed roughly stable at about 50 per cent of total.

And there should be caveats. If this idea becomes broadly accepted, consideration should be given to excluding rental units within owner occupied properties and/or rental buildings of six units or less. This type of housing, on very small lots and integrated within neighbourhoods in small buildings, provide a different service to the community and adhere to a substantially different land pricing dynamic. Building these projects requires no land assembly, for example.

We are entering a municipal election, during which candidates will once again be asked what steps they are willing to take to truly address Vancouver’s mounting housing crisis. Some will say all that is needed to fix the problem is to simply add new market rentals. But there is good reason to doubt that just adding tens of thousands of units will deliver cheaper units.

After all, Vancouver has, since the 1980s, been ahead of the North American curve rather than a laggard when calculating new housing units per capita. It's called Vancouverism and the downtown is the internationally recognized emblem for this strategy. If simply adding new units would bring housing prices down, Vancouver should have North America's cheapest housing. Instead it has North America's most expensive housing, by far (when measured by the gap between market rates and average household incomes).

Now is the time to have a serious conversation about adopting vacancy control in Vancouver. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: