“I have an easy solution. Just beat them up and ship them to Boston Bar or somewhere remote. Put a cheap tent. Let them live underneath it. Give them work to do like prison labour and provide food in exchange.”

“There are vacancies in our social housing system, and in local privately run single-room occupancy hotels, it’s just that some of those places are pretty awful and these people often prefer to live outdoors. Also, those places usually have rules, and these people, well... aren’t so good at following rules. And, finally, most of the people living in these tents are just straight up thoroughly mentally ill and refuse housing.” — Quotes from reddit Vancouver.

Since 2011, Pivot Legal Society has been working alongside people who live in camps or rely on public space to meet their everyday needs.

Addressing stigma is a part of this work. Sometimes, it’s obvious, like the reddit comments above.

However, stigma also informs how elected politicians, city staff and non-profit agencies respond to folks who rely on public space.

On Aug. 19, without prior notice, consent or consultation, residents of the Vancouver Oppenheimer Park camp and their advocates learned of the city’s plan for decampment.

More than 100 BC Housing units had been stockpiled in the preceding months, and residents were told they were being assessed for placement in housing programs throughout the city. Oppenheimer Park residents were given 57 hours’ notice to dismantle all structures.

Since then, Pivot has been on the ground, alongside Oppenheimer Park residents and organizers from groups like the Carnegie Community Action Project to advocate for the rights of those living in the encampment. Meanwhile, the city’s poor communication and lack of transparency has caused chaos and destabilized residents’ lives.

From the outset, the process to move people out of the park was unclear and opaque, creating confusion and suspicion as residents scrambled to determine their next steps. Municipalities across B.C. have identified decamping as a critical part of their homelessness strategy; the Union of BC Municipalities website hosts a 78-slide PowerPoint on “achieving voluntary decampment.” Yet the Vancouver park board deemed a two-page order sufficient.

Since that decision, Oppenheimer Park has made headlines across Canada. Leilani Farha, the United Nations special rapporteur on the right to housing, described the city’s approach as an “unacceptable and an egregious violation of the right to housing.” Pivot questioned what “voluntary decampment” means when tent city residents are threatened with legal action, offered unsuitable housing or have limited recourse.

Late last month, Vancouver city council approved a motion calling for “A Collaborative and New Approach to Oppenheimer Park and Other Public Spaces.” It directs city staff to “develop a collaborative decampment plan to go to the Vancouver Park Board for approval with the goal of restoring the park for broad public use.” Notably, the council failed to adopt an amendment to include park residents in the “collaborative plan.”

Elli Taylor, a Carnegie Community Action Project organizer, shared her apprehension about the motion.

“It calls for even more VPD, mental health cars (like car 87 and 88) as well as unlawful apprehensions,” Taylor said. “Furthermore, the motion does call for peer support, showers, and access to laundry, but it does not put a timeline on these items nor does it specify that this will take place in Oppenheimer.”

The motion doesn’t address the need for housing, or possibility of modular housing to replace the camp, Taylor said.

“The fact that BC Housing will sit in a communal meeting with residents of the park but the city staff refuse to, is another terrible monster,” she said. “When will we be accepted as real ‘citizens’ deserving of the same processes and rights as anyone else living in Vancouver?”

The high price for ‘supportive housing’

Housing has been a key demand of Downtown Eastside activists for years, but waves of paternalistic housing policy have led to concerns about control and coercion in non-profit housing. The 2019 Downtown Eastside Community Vision for the 100 Block of East Hastings reports that “it is abundantly clear that, in general, people want to have autonomy over their own housing and don’t want full non-profit control.”

For people who rely on public space, offers of housing can come with many strings attached, typically in the form of restrictive policies that protect the landlord. Residents may agree to extremely limited “guest policies” or continuous surveillance. Because people are not always informed about the agreements they’re being told to sign, the aftermath can feel like they’ve signed their lives away.

The uncertainty of life in these types of housing can have detrimental effects. A 2019 study by the BC Centre on Substance Use found both inadequate housing policies and tenancy supports were causing harm and contributing to the vulnerability of people who use drugs and experience evictions.

At first glance, supportive housing seems like a reasonable idea as one part of the housing spectrum. But an individual’s rights tend to diminish as they move along that spectrum and live in emergency shelters or transitional or supportive housing. This runs counter to Pivot’s work in advancing the rights of people who experience homelessness.

Supportive housing is generally distinguished by the 24/7 presence of building staff, who may be tasked with dispensing medications, everyday financial management or regulating who can enter a building. Staff may log everyday activity and keep track of residents’ lives through database systems.

BC Housing describes supportive housing as subsidized housing with on-site supports, suited to the needs of people who may require supports related to mental health, substance use and other challenges that increase the risk of homelessness.

In theory, the Residential Tenancy Act applies to supportive housing (unlike emergency shelters and transitional housing). However, there is little evidence that’s true in practice, as providers treat housing as a program element instead of a right.

Many people choose to live in informal shelters because they have the freedom to be near their friends, family and loved ones, without restrictive guest policies that isolate them from care and kinship networks. Some people avoid supportive housing because certain buildings are unsafe and unsanitary. When large camps are being shut down, some residents feel that they are slotted into housing programs that do not meet their needs or support them.

Were Oppenheimer residents informed that some supportive housing residents do not have protection under the Residential Tenancy Act? Were they told that buildings might have blanket policies that limit — or bar —guests?

Indigenous people — who have experienced displacement, dislocation, and genocide — continue to experience trauma as they are decamped. People are assigned housing without being adequately informed of their rights and the limits of a landlord’s power. This is housing that they do not want, and do not have a choice in. The imposition of supportive housing in these cases amplifies intergenerational experiences of oppression and power.

Imposing supportive housing on Indigenous communities disempowers people and has an impact on their self-esteem and self-worth. Cities, service workers and community advocates must deepen their understanding of Indigenous homelessness to better understand how their responses to displacement perpetuate harm.

Housing can meet the needs of residents without taking away their rights. Good supportive housing can build connections with neighbours and include space for culturally safe programming.

Erica’s story

I sought to better understand the impact of decamping Oppenheimer Park. I met with Erica Grant, a Nisga’a woman, who has been living in the DTES for five years. In that time, she has become a community organizer, graduated from the Community Action Network and is a member of the Carnegie Community Action Project.

When Erica first moved into her building, which is operated by a non-profit property management company, she assumed supportive housing just meant there would always be staff in the building. She now understands that supportive housing means much more. Staff also know about residents’ needs, they administer medications and enforce guest restrictions, with rules like “no guests before 9 a.m. and after 6 p.m.,” “no guests on cheque issue day” or “no guests for the first three months of your tenancy.”

The first supportive housing building Erica lived in was run by a non-profit. Both Erica and her partner got work in the building, but after her partner had a needle stick injury and requested protective equipment, she says that both were fired and evicted.

After that, Erica moved into her current place, another supportive housing building. This building has similar restrictions, and they are tightly enforced. When she had kidney surgery a few years ago, her children were barred from visiting because they do not have ID. Eventually, her daughter started dropping soup off for the staff to bring up to Erica, so that she didn’t need to rely on canned soup. Following the surgery, Erica was forced to recover too quickly.

Two of Erica’s children live in supportive housing buildings, and their experiences highlight the spectrum of quality. In her son’s building, anything goes. Violence and open substance use are the norm, and the staff does little to intervene. In her daughter’s building, a temporary modular housing program, the suites are nice and there is ample community space for programming that can bring neighbours together.

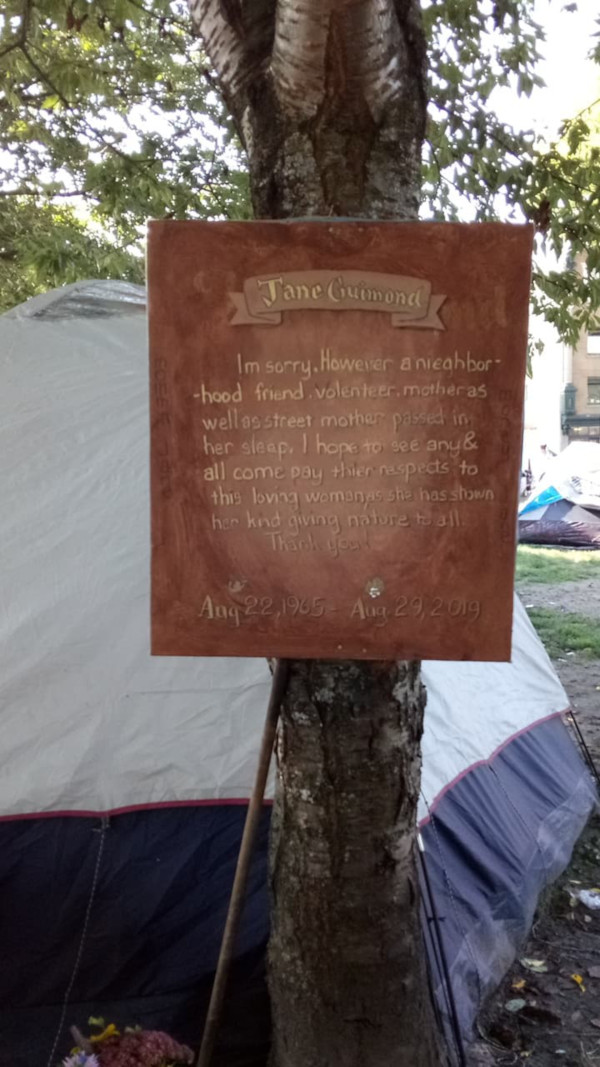

Erica says she knew a woman who lived at Oppenheimer and was offered housing across the city. This woman had lived among her best friends for months. Shortly after becoming a tenant at a housing site in Marpole, she died alone in her room. She could not afford the fare to come downtown, and she stopped seeing her friends.

She died of a broken heart, Erica says, isolated and away from her community.

Erica has heard the claim that “people in the park don’t want housing, that’s why they are in there.”

“That’s not true, not at all,” she says. People have come together in the park so they can unite and ensure the city takes notice. People in the park want housing, but they want quality housing that meets their needs. Some may want buildings that are staffed 24/7, while others want to live more independently.

What’s next?

Oppenheimer residents and their allies continue to uphold their autonomy and dignity, despite the city’s bureaucratic machinations, the tough-on-crime narrative of police and the widely held stigma around those who rely on public space. Rather than impose top-down solutions, it’s time for each of us — regardless of roles or relationships — to actually listen to the people who rely on public space. These folks have the lived experience and expertise that can inform well-crafted policies and practices to meaningfully address the problem of homelessness.

When I asked Erica what her dream for housing was, she described housing that affirms the community. Housing that would ensure residents are healthier and happier, not subject to discretionary and discriminatory rules and policies.

It’s time to put aside paternalistic notions and put people first. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: