On a cloudy spring morning in Vancouver’s Chinatown, Ms. Liang gently wheels her push cart down a steep flight of stairs. She doesn’t want to damage her precious cargo, a cardboard box that holds 24 empty bottles of Sleeman Honey Brown Lager.

She hikes back up to bring down two black garbage bags bulging with empty cans and bottles, the result of a week of evening strolls to the area surrounding BC Place Stadium and nearby Andy Livingstone Park to hunt for recyclables. Liang, who is in her 70s, takes her time because the building where she lives is over a century old and the stairs are narrow.

While Liang doesn’t know her stouts from her saisons, she knows that each can and bottle brought to the depot will earn her 10 cents.

On the sidewalk, she stacks the garbage bags on top of her box of bottles. There are a few holes in them, chewed open by rats drawn to the lingering sweet aromas from the beer and soda. But the stack holds together after Liang fastens them to her cart with her hooked bungee cords.

With her payload secured, it’s off to the depot.

Liang is one of a population of 600 to 700 customers who depend on the United We Can recycling depot on Industrial Avenue, just outside the low-income neighbourhoods of Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside.

Those who make regular trips to collect and return recyclables for income are known colloquially as “binners.”

Urbanization around the world has created excess waste of all sorts, which has in turn led to a form of work for people with limited employment options to collect and recycle it. In B.C., binning for cans and bottles has become a major type of waste-picking work. Low-income people in the province who turn to binning often lack adequate income supports. Or they are on a disability benefit that has a cap on how much they can earn through formal employment.

Over the past three decades, there has been increased public understanding of the experiences of binners, with credit to organizations like United We Can and the Binners’ Project, a local organization that seeks to improve economic opportunities for binners.

However, less is known about a binner demographic that is a common presence in Vancouver alleys, parks and sports fields, waiting at the ready for people to finish their sunny day beers: the immigrant senior.

In East Vancouver, they are mostly East and Southeast Asian women, some of whom have become familiar faces to the locals drinking all the beers and sodas that these seniors clean up after.

News media have mythologized a few who’ve struck up strong friendships in their respective neighbourhoods, such as an immigrant from Vietnam dubbed the “angel of East Hastings" for donating virtually all of her recycling profits to charities. Another in the area has been called the “grandmother of Hastings" by skaters at the park she frequents, because “she’ll come by your house to pick up cans, she’ll plant vegetables in your garden, she’ll bring you food.”

But behind these exceptional examples is a population of people who live in one of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods and are binning with far less fanfare. They face stigma from their families. They experience racism on the streets.

Yet they’re out collecting recyclables because it’s work they can pick up to pay the bills.

Shame and independence

“This is private work for a lot of people,” says Liang in Cantonese.

Two decades ago, Liang emigrated from China to Canada to help raise her grandchildren in Vancouver. After they grew up, she and her husband moved to Chinatown. As native Cantonese speakers who know little English, it was a comforting community to live in, with shops, services and other senior residents who all spoke the same language. Her husband has since died and her community means all the more.

“This seems to be a common story,” says Beverly Ho, the operations manager at Yarrow Intergenerational Society for Justice, a non-profit that works with low-income seniors in Chinatown. Once the child care is done, those grandparents opt to move out because they value their independence — or their families don’t want them in the home anymore.

In Chinatown, there is a significant number of seniors who have incomes less than $15,000 a year, Ho says. Among them are some who are undocumented or haven’t yet been Canadian citizens for 10 years, disqualifying them from the Old Age Security Pension. Seniors may not have family nearby, or have families who are low-income themselves and unable to provide financial support.

As a result, these seniors work. Ho says they engage in care work, such as taking care of children or minding other seniors who require assistance. Some work in food processing, but the most common place of employment is in restaurant kitchens.

For those seniors who don’t earn enough from their jobs to make ends meet, binning offers flexible work they can do at any time.

Liang has since retired from a decade of dishwashing but says she bins casually to “help out” with the bills and have a little extra money. While there are seniors who depend on the income from binning to survive, there are also those who live on tight budgets. What profits they can make from recycling offers them precious spending money. Liang is proud of every dime earned, though she worries about a decreasing number of affordable places in Chinatown for her to spend it, with the recent closures of restaurants like Gain Wah, Daisy Garden and Kent’s Kitchen.

Seniors are aware of the stigma behind working with waste. “They think it’s a bit shameful,” says Ho. Yarrow’s staff have noticed that seniors hide the fact that they bin and that they are discouraged from doing so by their relatives.

Almost two dozen Cantonese-speaking binners whom I approached at the United We Can depot, the Return-It depot on Kingsway and Clinton Park refused to be interviewed for this story. One who was willing to share about binning did not fit the demographic of the typical Chinatown binner, as she lives in a two-storey house in Burnaby, has an adult daughter who drives her to the depot and donates almost all of her profits to her church’s missionary work. Liang was the only one willing to share about her experiences in and around Chinatown using a real last name.

Custodians, street cleaners, city waste collectors and other formal, regulated workers who come into contact with waste that contains bacteria and bodily fluids are recommended by WorkSafeBC to use personal protective equipment like gloves. They will also receive mandatory training about safety. But while binners do similar work, the fact that they are unregulated, self-employed and likely low-income means that they do not have the same access to this protection.

What training Liang received for binning was through word-of-mouth. A former colleague at the restaurant she worked at set her up with a binner who brought her to the depot and showed her how to organize her recyclables and refund them for cash.

Aside from the hazards of handling waste, binning is also physically taxing for seniors, says Ho. Binners repeatedly bend over to pick up recyclables and carry heavy loads during commutes to a depot.

And despite living in Chinatown, a community that offers supports for Chinese seniors, there is also anti-Chinese racism.

Extra visible, extra audible

One of Liang’s neighbours, a man who looks slightly younger than her, is on his way to the depot too. He boards the 3 bus down Main Street with a full bag of recyclables in each hand, something Liang would never do.

“What if someone on the bus shoves me?” she says. “There’s been a lot of anti-Chinese racism during the pandemic."

In Chinatown these past three years, hateful graffiti has been scrawled on windows. In random encounters, seniors in the neighbourhood were physically attacked and the targets of aggressive, racist remarks. One attack in 2020 took place on a Chinatown bus, starting with a man telling two East Asian women wearing masks to “Go back to your country. That’s where it all started.”

“A lot of seniors do face overt anti-Chinese racism that [other visibly Chinese people] don’t face because of youth or ability to speak English,” says Ho at Yarrow.

Racism is enough of a regular occurrence that it shapes the daily routines of some Chinatown seniors like Liang. She also knows that binning makes her extra visible and extra audible, carrying rattling recyclables.

With the attacks in mind, she opts to walk the half hour to the depot instead, watching her neighbour speed away on the 3 bus.

“I just treat it as exercise,” she says. Wearing a sweater and comfy sneakers, she’s ready for the commute.

She might even spot an extra container along the way. Walking down busy Main Street, there’s something glittering on the road. It’s a can of Canada Dry cranberry ginger ale, flattened paper-thin by passing cars. Liang waits for a gap in traffic before stepping off the sidewalk curb to pinch it.

“The depot still accepts them like this,” she says, adding the wafer of a can to her bag.

Aside from racial discrimination, senior binners of colour are disadvantaged compared to the white counterparts if they don’t speak English. Some building managers and bar owners are known to form relationships with binners and offer them recyclables on the regular. But Liang and binners like her don’t speak English and they can’t access these kinds of casual relationships of support.

That being said, for all the stares and discrimination she’s experienced, there are people who come up to her at parks to offer her a can or bottle.

“Some white people know to say ‘lay ho’ or ‘jo sun’ to me,” she says with a laugh, surprised to see hear them using the Cantonese phrases for “how are you” and “good morning.” “There’s good and bad people of all backgrounds.”

‘I didn’t know how to protest in English’

There are already a dozen binners sorting their cans and bottles when Liang arrives at the United We Can depot. They each have a trolley on which they are placing recyclables into trays, which can fit 24 cans or bottles each. There’s another Chinatown resident here, a man wearing a red cap with the logo of the Ming Pao newspaper, who greets Liang in Cantonese with a “Good morning, sister!”

Liang grabs her own trolley and a stack of trays. Untying her bags, she goes straight to work sorting like with like. It’s the soft drinks she organizes first, putting the cans of Coke and Sprite together. Then it’s tallboys, an assortment of Sapporo and local craft beers. That leaves glass and plastic bottles remaining.

A voice behind her says, “You can’t take all of those trays.”

It’s a tall white man in his 40s or 50s who has just arrived at the depot.

“I need them,” says Liang in Cantonese.

The man approaches to take the trays from her.

“No, no, no!” she says.

The man grabs about four from her stack, knocking the rest to the ground.

“Fucking chink,” he says as he walks away.

Liang is shaken. But it’s not the first time something like this has happened.

“I’ve had entire bags stolen before,” she says. “Once was at the depot. I remember it was a white man with a hat. He yanked my bag out of my hands. I didn’t know how to protest in English. I tried to tell the staff at the depot, but they didn’t seem to know what to do. The man ended up refunding everything I had collected and taking the money.”

She’s never met staff at the depot who could speak Cantonese. The only hint of Chinese is a sign that says “Don’t mix pop cans and beer cans.” While this has made it hard to communicate with the organization on which she relies to get her binning money, she notes that the staff have helped whenever they could.

There was a second occasion on which a man stole her bag of recyclables at the depot. It was worth about $10. Liang started crying, which frightened the man enough that he ran away. The staff offered her a seat, a cup of water and pointed to the security cameras to let Liang know that they were watching. The next time Liang went to the depot, the staff gave her a bag of recyclables, which she suspects was recovered from the thief.

“Another time, someone stole my hat!” says Liang. “Right off of my head. I followed him to the counter and told the depot staff, ‘No, no, no!’ I pointed to my head and I pointed to him. I didn’t want them to accept his cans and bottles. And then he gave me my hat back.”

Making ends meet

When Liang finishes sorting her recyclables, exactly an hour after she started, she takes out a homemade notepad made up of old envelopes and receipts and begins doing some math. She estimates that she’ll be receiving $62.40 today.

She wheels her trolley over to the counter and the attendant tallies her haul: 237 cans of beer, 171 cans of pop, 118 plastic bottles, 62 glass bottles and 34 beer bottles. The only two containers that are rejected are a yogurt drink and a bottle of olive oil. That means Liang was only 20 cents off from her tally.

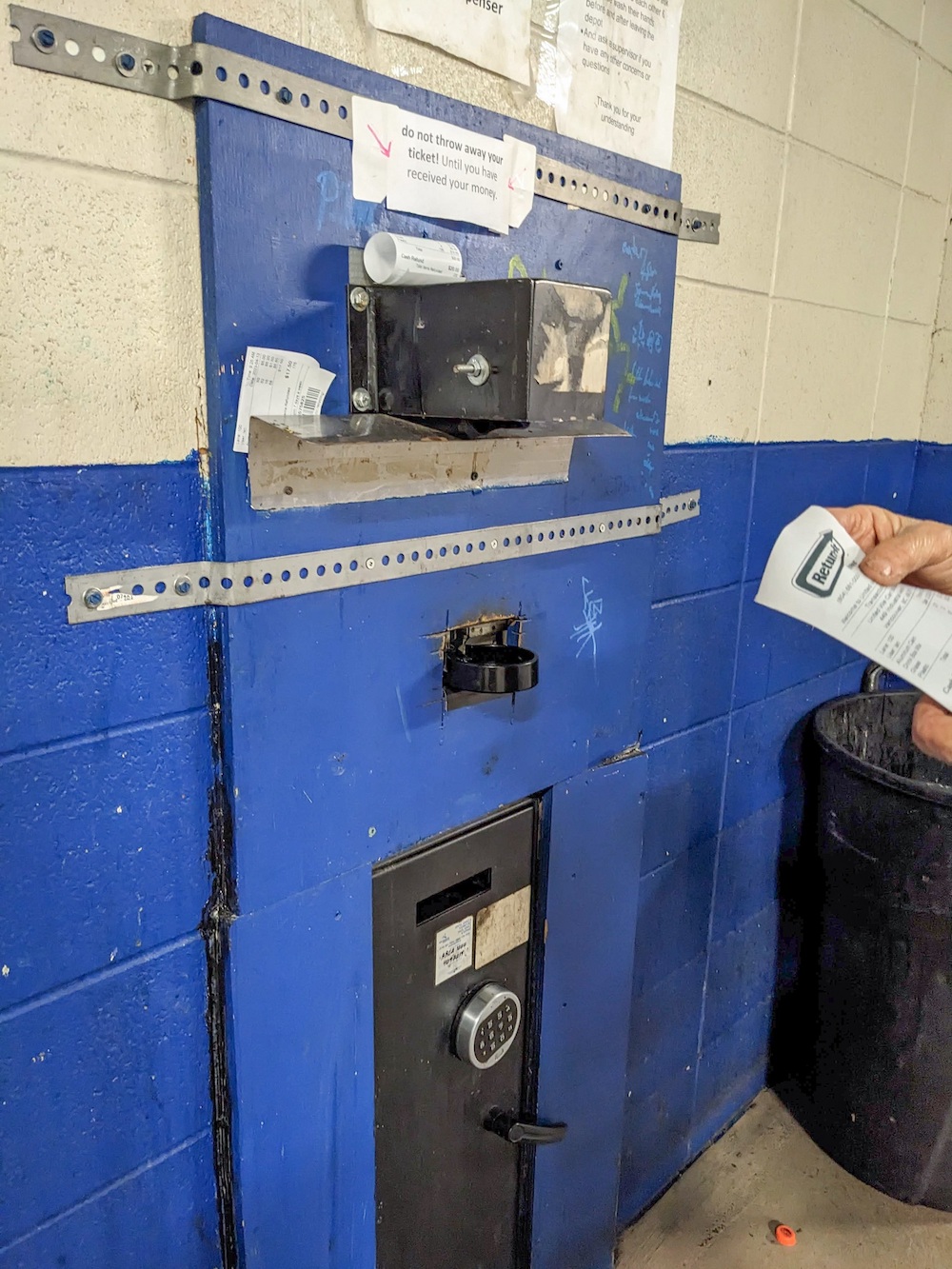

The attendant hands her a ticket, which she brings to a machine inside a wall on the opposite side of the room.

She inserts her ticket into the slot and out comes her cash refund.

“Over 60 dollars!” she says with joy.

It’s the result of about a week of casual collecting. The non-profit Binners' Project estimates that a full-time binner makes about $50 a day. That’s $6.25 an hour, almost a third of what a B.C. worker makes for minimum wage, for work that’s taxing for seniors in particular.

“I know some do it to pass the time or as a social aspect,” said Ho at Yarrow. “But at the same time, I think we can grow a stronger social service support network so that seniors don’t have to work… I think seniors should be able to retire completely, age in place and not have to worry about making ends meet or finding affordable food sources and culturally appropriate services.”

After Liang washes her hands and her bags at the depot, she starts her walk back to Chinatown.

With the $62.40 in pocket, she’s thinking of taking her friends out for dim sum. Maybe she’ll spot a few cans or bottles on the way there. She plans to be back at the depot next week. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: