When the smoke and ash started seeping into her home and hallways, Billie Sheridan knew it was time to escape. The official evacuation order that would clear the entire city of Williams Lake had yet to be sounded. But already three of Sheridan’s sons were gone. They’d left the morning before because it was too hard for one of them with asthma to breathe.

Now wildfires — among a swarm that burned across British Columbia that summer of 2017 — were fast closing in on the central Interior city’s 10,500 residents. Sheridan and her daughter-in-law loaded themselves, the dog and their belongings into a minivan and started the 240-kilometre drive up Highway 97 towards safety in Prince George.

Billie’s wife Crystal Sheridan, a nurse, stayed behind to care for and help evacuate elderly residents. Billie’s mind turned to Crystal as she drove. She hoped for the best, assuming they’d all be reunited soon enough with stories to share.

“We didn't anticipate the length of the time,” Billie recalled. “We were hoping that this was only going to last a few days.”

But days turned into weeks, then stretched past a month as the Sheridans shuffled from place to place.

While caring for her patients, Crystal Sheridan’s hip replacement broke. She was eventually medevacked to Vancouver after the rest of the Sheridans made their way to the Lower Mainland. There, the family bounced between the hospital, a hotel and staying with family.

While the official evacuation order for Williams Lake lasted almost two weeks, the fires triggered a series of health and safety issues for the Sheridans that caused them to leave early and stay away more than twice as long as officials mandated.

“It was mentally and physically exhausting that summer,” said Billie Sheridan.

The family eventually found lodging at Honour House, a home in New Westminster for Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans, emergency services personnel and their families to stay while receiving medical care. “We were so lucky and so fortunate,” Sheridan said. “That facility holds a very important place in my heart.”

That tinder dry wildfire season of 2017 was one of the worst in B.C. history, forcing an estimated 65,000 people out of their homes. Many of those evacuees learned Billie Sheridan’s hard lesson — that as climate disasters increase in their frequency and intensity, those who seek refuge can expect to be uprooted for long stretches.

It’s already happening. The Tyee analyzed available data for the past six years to discover the average length of time people are being evacuated in this province — it tops three weeks.

That’s a span of time that experts say the B.C. government hasn’t reckoned with — but must if it is to succeed in its declared effort to beef up its support systems for evacuees.

Bowinn Ma, who heads the newly created B.C. Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness, acknowledges the province needs to catch up. Many of B.C.’s emergency support services “were designed in a time before the realities of climate change” and haven't evolved since the early 2000s, Ma told The Tyee in an interview.

B.C.’s Emergency Support Service program provides people aid during the first 72 hours of a crisis to give them time to reach out to other support networks or get insurance to kick in, said Ma. It is a “short-term immediate measure to help people during emergencies.”

But emergencies are changing, said Ma, and the “duration of these displacements is really, really getting so much longer than what we used to see in the past.”

This year the province invested $180 million into the Community Emergency Preparedness Fund to help communities and First Nations be ready for emergencies like floods and wildfires — bringing the total to $369 million since 2017. Communities can apply to use the money for building dikes, evacuation planning and emergency support services recruitment and training.

How data can build resilience

The Tyee worked with Vancouver-based data scientist Jens von Bergmann to create an in-depth profile of evacuations in B.C. Combining open data and census data we were able to uncover an estimate of how many people are being evacuated, for how long and who they are.

People in B.C. are being evacuated, on average, for approximately 22 days, according to figures over the last six years. Since 2017, there have been over 1,400 evacuation orders across the province and about 97 per cent of those lasted over three days.

Over that time, the B.C. government told us they spent over $49 million to support approximately 113,453 evacuees through the Emergency Support Service program. The last fiscal year cost almost half of that funding at $23 million.

“The whole framework is out of date,” said Tyrone McNeil in reaction to the Tyee’s findings. McNeil is chief of the Stó:lo Tribal Council and chair of the Emergency Planning Secretariat which is creating a Coast-Salish led flood management strategy for the 31 First Nations by the Fraser River.

The province’s emergency support service system should be designed not for evacuations of 72 hours but for displacement lasting a full month, McNeil said. “Right now, it's all too short-term.”

Making matters worse, “There's too much bureaucracy involved.”

It’s hard for evacuees and their First Nations or municipalities to keep going back to the provincial government to get extensions for support, McNeil explained.

“While there's a lot of excellent measures in place, I think that the complexity and the frequency and the severity of the problems that are now coming down the pipeline are not things that the system was equipped to deal with,” said disaster displacement and community engagement specialist Sarah Kamal, who is based in Vancouver and works with First Nations in B.C.

As climate disasters intensify, scientists warn that stories like Sheridan’s will become more common. Canada is warming at double the rate of the rest of the world and communities across the country face rising sea levels, wildfires and floods, according to a 2019 report by the federal government.

No one is keeping track of how long people in B.C. are actually away from their homes and what populations are most affected. This data is crucial to ensure we have the right programs to prepare for disasters and support evacuees and communities, as Kamal noted.

Bracing for the future or extreme weather disasters in B.C., Kamal said, means attending to “a major gap” — the same one cited by McNeil.

“There's no plan for what happens when evacuations lengthen out and become longer displacements over months, even years,” said Kamal. “That causes additional trauma and uncertainty for communities that are already suffering.”

Indigenous people are most likely to be evacuated

It can be overwhelming to think about how we prepare for the unknown, said Kamal. But having more data about evacuations allows decision-makers to make informed choices on what programs and populations to support.

Fires were the main reason communities were evacuated. Fires also displaced the most people, followed by floods then sinkholes and landslides.

Most evacuations for fires, floods and landslides in B.C. last more than three days

Fires

Floods

Landslides & sinkholes

The Tyee’s analysis drawing on von Bergmann’s data work also showed that Indigenous people across B.C. are about four times more likely to experience an evacuation than non-Indigenous people. Indigenous people living on reserves across Canada are 18 times more likely to be displaced, according to the federal government.

“Our communities are impacted a whole lot more than others based on their geographic location, based on their inability to have funding to fire smart their communities, based on limited capacity,” McNeil said.

The colonial legacy of how and where reserves were structured and the uneven distribution of resources to Indigenous communities means that they are more likely to be harmed by climate disasters and displacement, said Kamal. She recently published a policy scan looking at climate displacement around the world and what Canada can learn.

While there weren’t significant differences; people in the bottom half of the income distribution, homeowners and people not in the labour force were more likely to be evacuated over the last six years. These demographics also reflect the makeup of rural and remote communities who disproportionately “experience social, economic, cultural and health impacts from climate change compared with urban centres,” according to a report by the federal government.

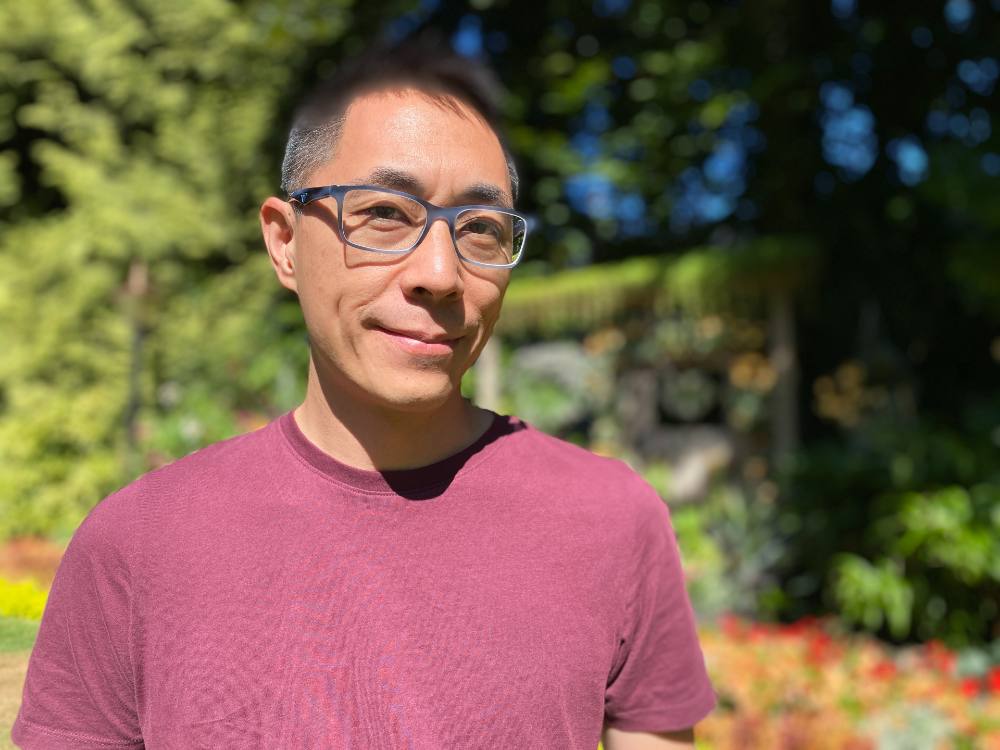

Putting the average time people are evacuated at three weeks in B.C. seems realistic to Vincent Fung, a data analyst. Fung has worked in international humanitarian and disaster response for over 15 years and has crunched displacement data from around the world. He was formerly a monitoring expert for the Asia Pacific region with the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

Getting accurate data to help inform policy is one of the goals of the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The organization describes itself as the world’s definitive source of internal displacement data and uses public data and the media to count displacements from disasters and conflict.

Around the world, extreme weather is forcing people to leave their communities. The last few years saw major flooding in Pakistan, wildfires across Europe and major hurricanes in the U.S. Almost 24 million people were displaced around the world by disasters in 2021, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The centre estimates 60,000 of those displacements were across Canada. Their numbers are based on a variety of sources including open data and media reports.

“It’s happening everywhere,” Fung said, including in B.C. as he pointed to major flooding in 2021 from atmospheric rivers and seasonal wildfires.

Evacuations: A brief primer

When disasters strike in B.C., emergency officials will often use evacuation alerts and orders to move communities out of harm’s way. Alerts are sometimes issued if there is a nearby disaster like a flood or wildfire that could threaten people’s safety. Alerts allow people to get ready for a possible evacuation, plan an escape route and prepare a bag of belongings to take in case an evacuation order is issued.

An evacuation order is given when emergency officials believe it is no longer safe to stay and residents should leave immediately. During big events, people often then are directed to Emergency Support Services Reception Centres in neighbouring communities where they can get information and resources. These support services are generally available for up to 72 hours and can be extended in extreme situations.

An evacuation order is lifted when emergency officials have decided it is safe for people to return home but an alert might still be in effect. Our analysis counted the length of an evacuation as the time from when an evacuation order was given to when there were no more alerts or orders for the area.

Just because an evacuation order has been lifted, does not mean that evacuees will have a safe place to return to or will choose to return. Long after an evacuation order ends people may face rebuilding their homes and communities.

An estimated 13,500 people were evacuated after atmospheric rivers hit southern B.C. in November 2021, according to the Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness. Homes, highways and critical infrastructure were destroyed, making it the most expensive disaster in the province’s history. An analysis by the Globe and Mail estimates it will take nearly $9 billion to rebuild.

Major disasters across Canada are costing billions of dollars in insured damages

During the November floods, the entire city of Merritt was evacuated. While some people were able to return a few weeks later, it took until June 2022 for all the evacuation orders to be lifted. Over a year later, some evacuees were still living in hotels and are only now moving into transitional housing.

B.C. officials working to keep pace with intensifying climate disasters might look beyond Canada’s borders for examples of how to do more. While 2021 flooding in B.C. was described as “unprecedented,” across the globe in Indonesia floods force thousands of people from their homes every year during the rainy season between October and March.

Responding to disasters is a priority for the nation made up of thousands of islands where one in four people live in high risk flooding areas.

The country’s National Disaster Management Agency publishes an online, public database on the number of evacuations, destroyed housing and affected people. “They have data that goes back to the 1800s,” said Fung who points to the disaster-prone archipelago as an example of how systemic reporting and open data on displacements can help improve disaster response and recovery.

The data has allowed authorities to predict future displacements and strengthen warning systems, giving people more time to prepare and evacuate. It’s also helped local authorities and non-governmental organizations manage stockpiles of food, medicine, blankets and clothes for flood survivors.

People want more information to help them plan for climate change. A recent survey commissioned by the Insurance Bureau of Canada found that nearly nine in 10 British Columbians believe it’s important to have access to data on flood-prone areas and nearly seven in 10 said they would consider relocating to a safer area if the government paid market price for their property.

One tool newly crafted for such a purpose by two Canadian real estate platforms ranks risk factors for hundreds of thousands of homes across Canada. Demand for such transparency is likely to rise.

“The first thing we need to understand is the risk profile of these communities,” said von Bergmann. “Once we understand these risks better then we can think of how to mitigate them.” Other responses can vary from building climate resistant infrastructure like dikes or, in some isolated cases, relocating.

“We need awareness so that people can make informed decisions about where they live and how they deal with these risks,” von Bergmann said.

That data can also be used to help address gaps in insurance policy that leave flood survivors with not enough or no coverage at all. Providing accurate flood risk levels can help guide society towards less risky decisions, according to a federal task force on flood insurance and relocation.

Right now, the nation’s yearly flood risk, for residential areas alone, sits at $2.9 billion. The authors also warned that without carefully designed flood insurance policies, access to proper insurance will remain a challenge and leave more risk “on vulnerable Canadians and people living in high-risk areas.”

The provincial government is currently developing a risk data strategy as it modernizes the Emergency Program Act. The goal is to provide public data that provides risk and hazard information at provincial, regional and local levels.

The province is also digitizing much of its processes which were previously mostly paper-based. This should provide easier access to data about evacuations, said Minister Ma.

While data won’t alone solve challenges, it gives us an opportunity to plan better. A common maxim that has stuck with Fung is: you can’t manage what you can’t measure. With more information about displacements, agencies and governments can better manage and budget what supports they are able to give, Fung said. It also provides individuals with more agency if they know an evacuation could last several weeks.

Planning for future disasters

Looking back at how past evacuations have unfolded is helpful but it’s also important to consider how our population is changing over time to ensure that our preparation, response and recovery to future disasters can meet people’s needs, Fung said. When that fails, the consequences can be deadly.

Fung pointed to how seniors and people living in long-term care homes were especially hard hit by COVID-19. Today, governments are still trying to fix the system and update standards. In the coming decades our population will age and B.C. is expected to see one of the highest proportions of seniors aged 85 and older in Canada, according to Statistics Canada estimates.

When it comes to climate disasters, people on fixed income like pensioners or retirees out of the labour force could face unique challenges if they have to rebuild their homes.

“Disasters don’t care about age,” said Fung. “Whatever they're receiving from the government or from their own pension, it's not going to cover the cost of rebuilding; especially if we're talking about inflation and the cost of supplies.”

Disasters also don’t care about skin colour, said Kamal. Over the next 18 years, the Indigenous population is projected to grow faster than the non-Indigenous population across the country. B.C. will likely have one of the highest populations of First Nations people in the country, according to projections by Statistics Canada.

It’s important that any response includes community leaders so that things like traditional foods, activities and cultural healing can be available to help reduce stress, Kamal said.

When an entire community is evacuated, the response should look more like humanitarian aid rather than the current emergency support services that are provided, said McNeil. The response needs to factor in the growing size and scale of disasters as well as culture, spiritual and dietary needs. He’s calling for more authority and more support for First Nations to address the needs of evacuees.

“There's got to be better financial support available,” McNeil said. Indigenous communities have set up reception centres for Indigenous and non-Indigenous evacuees but need to be reimbursed for those costs in a more timely way, he said.

While McNeil is pleased to see the government provide more funding for emergency planning, he’s heard communities have waited anywhere between one and two years to be paid back. It needs to be more manageable, he said.

The Emergency Support Service program is geared to help evacuees for the first three days of their ordeal but money for needs like accommodations and food can be extended beyond 72 hours when requested. Since June 2022, the province has provided extended support for evacuees of 77 events. These events also included apartment fires.

Thousands of evacuees rely on government funding to help with basic needs after a disaster, every year

Last year, the province spent almost $23 million to provide emergency support services for over 34,600 evacuees, according to data provided by the ministry. Over the last five years, the average amount spent on evacuees increased from $258 per person in 2017 to over $500 per person every year since.

“We provide funding for essentials like lodging, food, clothing, incidentals and transportation,” Minister Ma told The Tyee. “In terms of lodging, it's very often hotel rooms.”

But living out of a hotel room for weeks or months on end is not ideal for people’s well-being or for cost efficiency. Now the ministry is looking to answer how the province evolves supports over medium to long term evacuations and identifying the gaps in services, Ma said.

That’s a key target for action, said Kamal. “We have in our heads through public messaging, this idea of the 72 hours.” But if disasters are lasting longer that needs to be more clearly communicated to the public. “In that process of the 22 days, you're not in one location, you're moving around, you're trying to cope with a great deal of uncertainty,” she said.

Having a better idea of how long an evacuation might last can help with not just planning but lower stress, Fung said. “That psychological impact really eats away at you. And it’s not knowing sometimes that really causes that.”

Communities can take a proactive approach when knowing that evacuations are lasting longer and the government support might not be available right away or for their entire displacement, Fung said.

“We have heard loud and clear from local governments and First Nations communities, the need to support capacity building within their governments,” said Ma. She pointed to the Community Emergency Preparedness Fund that has a dedicated stream for Indigenous cultural safety in emergency management.

‘If this ever happens again’

During the summer of 2017, wildfires across B.C. prompted the government to declare a state of emergency that lasted from July 7 to midnight of Sept. 15. The fires around Williams Lake did claim some structures, but thankfully no residents died and the vast majority of homes were spared.

Billie Sheridan and her family still live in the home they fled. As she reflects on what they endured, she is a reminder that those who have lived through calamities carry within them useful data of a sort that is personal. They have experiences to share.

Sheridan hopes that disaster survivors will share their stories and the people tasked with improving emergency responses will listen to better inform their policies.

“For somebody that's lived through it, it's hard. You're leaving your life behind. You're uncertain if you're going to be homeless. You're uncertain if you're going to come back home,” Sheridan said.

She said more information before and after the wildfires and a realistic return plan would have helped ease the anxiety of being away from home for so long. It was agonizing, she said, to be glued to the news waiting for any word, but only getting vague details from officials.

“A lot of times, they would just tell us that we're hoping to get people home as soon as possible.”

After her ordeal, she feels the next time she will be more ready — and so will her community members.

“I think Williams Lake knows that now. If this ever happens again, they are prepped and ready to go at a moment's notice.”

This is a part of ‘Bracing for Disasters,’ an occasional series investigating how to support evacuees and save lives as extreme weather worsens in B.C. Next Monday, meet survivors sharing precious items they managed to save as they fled catastrophes.

With files from Aldyn Chwelos.

Read more: BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: