Just about every inch of Harold Steves’ house has some project waiting for him. At 85 years old, most people would’ve retired already. But Steves kept on getting elected, putting in five decades as a Richmond city councillor and four years as an MLA. The legendary politician and environmental activist has fought everything over the years from a supertanker port, a plan to dump raw sewage into the Fraser River to unrelenting attempts to buy up farmland for industry and new homes. But in 2020, after the 60th wedding anniversary with his wife Kathy, Steves decided it was time to retire. In 2022, with the October election of a new council, Steves finally made his exit.

These days he’s working on something else much closer to home: renovating the house.

It’s a gloomy November Monday and a new door was just delivered to the Steves’ farm at the western end of Steveston Highway, the only farm left in the area. The family cows, Belted Galloways, usually graze in the nearby pastures by the boggy city’s dike, with a sweeping view of the Georgia Strait on one side and the suburban likes of townhouses and cul-de-sacked mansions with pools on the other.

Steves, who usually sports a plaid shirt but is wearing a sweater vest on this cold morning, is very happy about the delivery.

“The whole house has been torn apart!” he says.

The Steves farmland on which the house sits has been passed down through the generations. It was first purchased by his great-grandfather in 1877, even before the founding of Richmond. In 1917, it was grandfather Joseph Steves who selected the plan for the current Edwardian farmhouse, with Craftsman touches, out of a catalogue. Steves says he “yo-yoed” in and out of living in it over his early life, moving in permanently with Kathy when his parents died.

This is the first winter since he was a child that cows haven’t been around. His son Jerry took them up to their ranch at Cache Creek for the winter — which leaves Steves with more time to tackle the long list of things he has to do.

The door has arrived at the perfect time because the contractor will be done with the porch next week. After that, the old carpet inside the house will need to go. He’s still producing heirloom seeds at the farm, including the family’s alpha tomato, which yields fruit a full month earlier than other varieties. The basement needs to be cleaned in time to welcome visitors for an open house next year. There’s also something in the garage he’s been tinkering with: a 1950 Dodge convertible, just like the one he used to carpool to university in.

“None of my friends have passed away yet,” says Steves, “so before anybody dies on us, we gotta take it out for a ride.”

On top of all this are the projects he’s undertaking for the city. There’s the fisheries museum he’s proposed for Steveston, his last big council motion, which he will likely consult on. There are old photos he’s scanning for archives, which include those taken by his aunt Jessie of her students at the nearby school for Japanese locals before the wartime internment. There’s historical writing he’s putting together, everything from his own experiences to his late family’s diaries to the records of Richmond archaeologist Leonard Ham, who passed them on to Steves before he died. There’s Twitter, an arguably less-important platform where he has almost 10,000 followers, but he’ll spare a moment here and there to chime in on farming, politics and climate change with other British Columbians.

Of course, retirement means more family time too. His young granddaughters, who are off from school, are hanging around the farm this morning. Upon spotting this reporter with their grandfather in the dining room, they cry, “Hey, where did you come from?”

“I’m so busy I hardly miss council,” says Steves, who was the longest-serving sitting politician in Metro Vancouver.

That said, council is in session today at 4 p.m. and he still plans to tune in.

The Steves of Steveston

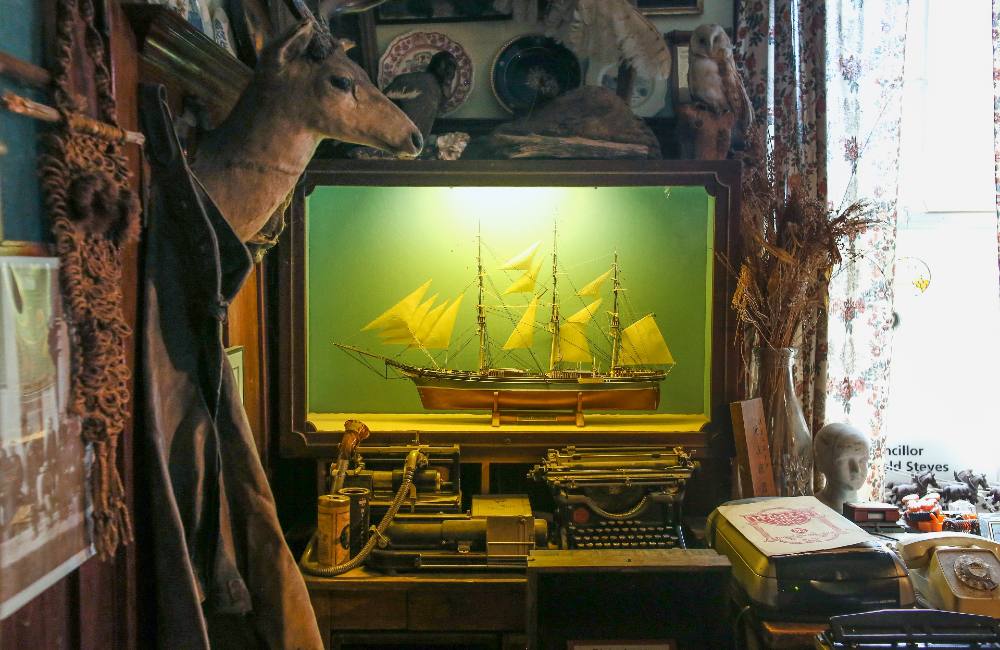

The Steves house is a trove of family history. In Steves’ home office, the HP laptop on his desk feels anachronistic surrounded by the old portraits, plates and plaques that cover the walls. Taxidermy of Richmond water birds perch on the shelves, many of which were stuffed by Steves himself.

One of the prints on the wall comes from 1867, a picture of the Fathers of Confederation in Charlottetown. “There’s a W.H. Steeves in there,” he says, pointing to the ancestor with whom he shares a slight resemblance.

The family cows are watching over him. While the living room has framed portraits of family, Steves’ office has portraits of Holsteins in a row just under the ceiling.

His great-grandparents were the first to import purebred Holstein cattle to B.C., supplying milk to nearby Vancouver. Steves has a whole album of sepia-toned cow pictures, starting with a bull on the first page named Sir Canary Mechtilde.

“I used to try and play it down,” he says. “It just seemed kind of strange. It took a while to get used to it.”

While great-grandfather Manoah Steves was the first white settler in the area in 1877, arriving from New Brunswick, Steves always notes that the family were not the first people to live there. This part of Lulu Island, the main island of the City of Richmond, was once home to two Musqueam summer villages. A few years later, a son of Manoah and his wife Martha, named William Herbert, established lots in between those two villages for a new town called Steveston.

“Instead of building on high land, they drove posts into the ground and built the whole town on stilts,” says Steves. “Only white people would build in a swamp; the First Nations people were on solid land on each side.”

In its early decades, Steveston flourished as a fishing community with a row of productive canneries. The area has since suburbanized, but remains an active fishing port and is a popular destination for tourists from around the world but also locals looking for live spot prawns and hungry for fish and chips.

‘The little man who stood nine feet tall’

Harold Steves was a 22-year-old university student when he was pulled into the public eye.

In 1958, he applied for a permit to build a new barn and dairy for the family farm. It was rejected and Steves stumbled upon worse news. Two years prior, Richmond’s council had quietly rezoned the Steves farm, part of about 1,000 farms, for residential use. The farmers were angry, but didn’t know how to fight city hall. Many sold their land as a result. For the Steves, the city’s decision put an end to the family’s dairy business and hit them with heavy residential property taxes.

From there, Steves took an interest in politics. He had a friend named Bill Sigurgeirson who ran a Co-operative Commonwealth Federation club for young people in his parents’ basement. The party of farmers and agrarian socialists seemed the perfect match for Steves, who became a member. When the CCF teamed up with labour to form the NDP, Steves became the first president of the BC NDP Youth in 1961.

A few years later, Richmond proposed dumping its raw sewage into the Fraser River. Steves helped launch an anti-pollution group, which collected 10,000 names in a petition, more than the 10 per cent necessary to force a referendum. But the wily council said that the petition was invalid due to a technicality: it did not name the specific bylaw they were fighting. So the anti-pollutionists decided to run candidates for council, one of whom was Steves.

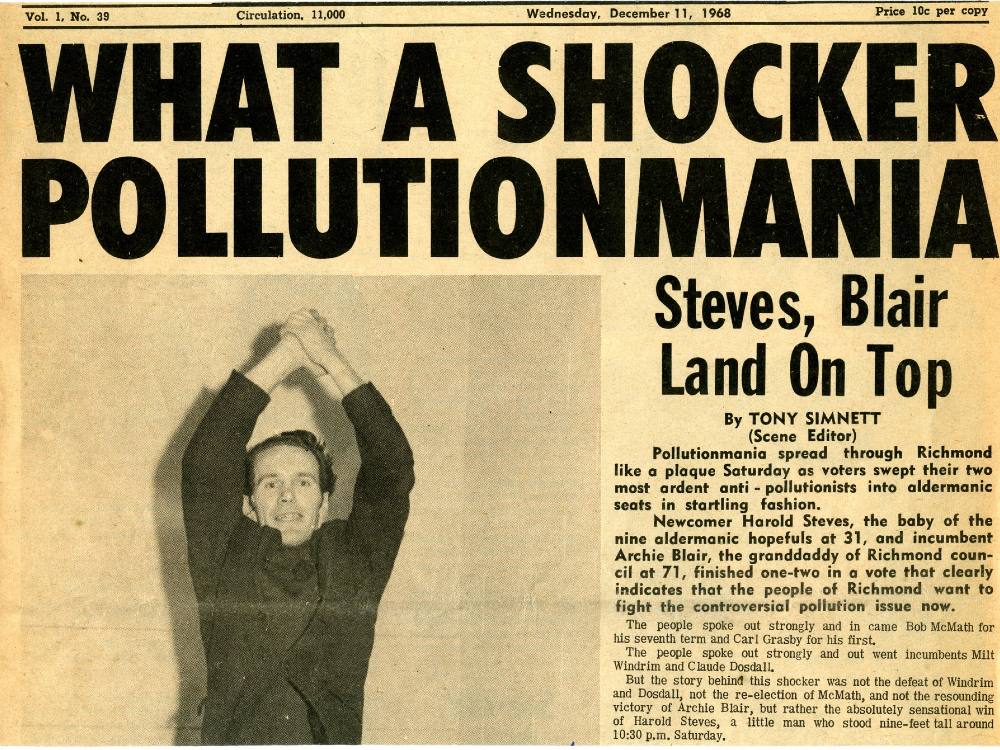

The Richmond Scene newspaper called the election a “shocker.” Steves was elected, along with another anti-pollutionist. The paper called him “the little man who stood nine feet tall.” With 1968 being the year of Trudeaumania, media dubbed the election “Pollutionmania.” Their victory resulted in secondary sewage treatment for the city.

“It was the Japanese community largely that pushed to get me elected because they were the main fishing group at the time,” says Steves, who remembers a hundred people waiting in line to vote at the local community centre with 15 minutes before the polls closed.

After his first term in council, Steves made a run for provincial office and was elected MLA for Richmond with Dave Barrett’s New Democrats in 1972, the first time the party had formed government in B.C.

It was the chance for Steves to push an idea that he had kicked around at NDP conventions. Not long after the Richmond rezonings that shut down his family dairy, Steves heard from the village blacksmith in Surrey’s Whalley about something called a land bank. That’s why was being used in Saskatchewan to protect farmland and Steves was determined to introduce something similar to B.C.

The NDP found the idea too radical in the 1960s, but the loss of farmland, about 6,000 hectares each year, became a growing problem that even the Social Credit government took note.

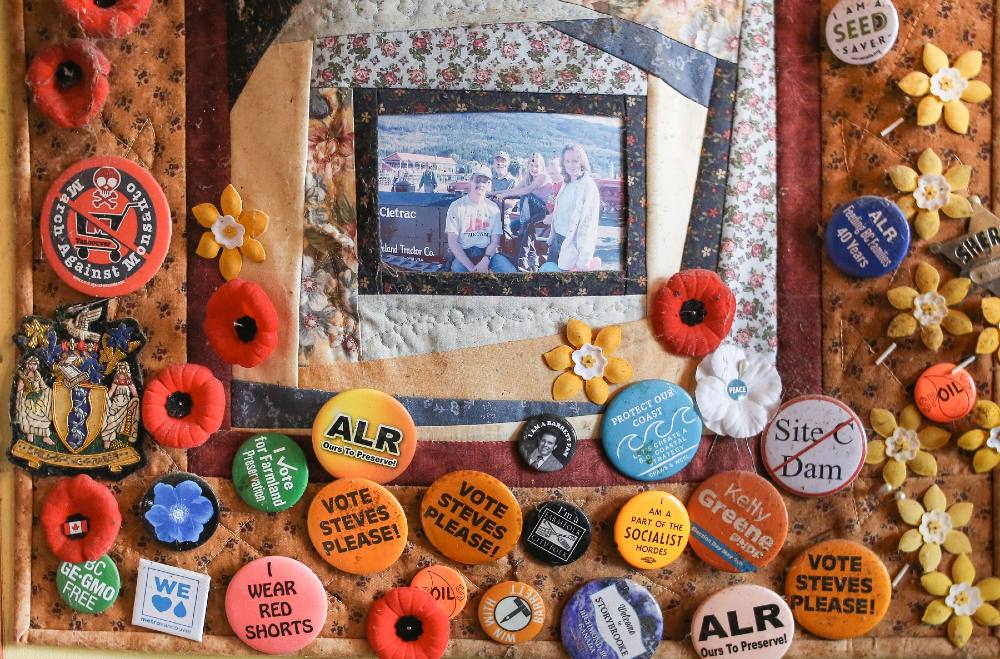

The New Democrats eventually accepted a land bank as part of its platform in time for their victorious 1972 election. Steves had the ear of agricultural minister David Stupich and in 1973, the Agricultural Land Reserve was created, only permitting the land within it to be used for agricultural purposes.

Today, the ALR covers about 4.6 million hectares of protected farmland. The opposition, upon its creation, called it “communist.”

By that time, Steves, who has a degree in agriculture, had already been worrying about an existential threat to food security for over a decade.

“I was a teaching assistant for a graduate course on the future of agriculture,” says Steves, who earned his degree at the University of British Columbia.

“The world’s scientists had just announced in 1957 that the climate was changing. And they predicted that within 50 years, you’d be able to sail a ship through the Northwest Passage, which is exactly what happened. Part of our seminar asked: as the climate changes, how does that affect agriculture? We didn’t know.”

When they took the neighbours away

There’s a vintage pie case in the basement that Steves is cleaning up for next spring’s open house. “Plant a victory garden,” reads a wartime poster on the wall, telling the home front that “Our food is fighting.” Also kicking around is an old mechanical cash register. During the Second World War, this was where his parents set up a canteen for the troops. Apparently they didn’t like camp food and occasionally visited the Steves’ for breakfast, lunch and slices of apple and lemon meringue pie.

When war broke out in 1939, Steveston became Fort Steveston, fully manned and operated by the 58th Battery of the 15th (Vancouver) Coast Regiment of the Royal Canadian Artillery.

Steves was two years old at the time. Barbed wire and barricades were a common sight. When he was old enough, he’d watch the testing of the anti-aircraft gun from his front window, which his parents were told to keep slightly open, because the sound of the gun firing could shatter the glass.

Even Steves the toddler was conscripted for a special role, that of the fort’s mascot. It was a formal affair, with Steves wearing a scaled-down army uniform while inspecting the troops.

Steveston was home to a prominent Japanese community very soon after the town was founded. They were drawn by the fishing industry, particularly salmon, though it wasn’t an easy living, with booms and busts over the years. Still, many chose to put down roots in Steveston, with a Japanese population of about 3,500 at its peak. Japanese residents established their own hospital, because the other local hospital refused to admit Japanese patients, and its own school, where Steves’ aunt was a teacher and welcomed students of any background.

Then in December 1941, Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbour. “I was only five years old when they took my playmate away,” says Steves. “She lived across the street, Fumiko. Her father Fumio Kojiro was the principal of the Japanese school and his wife was a teacher. And they took him right out of the school. His wife came over to our place to get my mom and dad to help.”

When the federal government decided to forcibly intern Japanese Canadians and seize their property in 1942, Steveston’s community leaders like Fumiko’s father were the first to be taken away. Steves’ father went to a local meeting to protest the internment and came home angry: someone had called him a “white jap.”

Steves remembers the day when the rest of the Japanese community was evacuated. His mother took him and his brother, who was in a baby carriage, to say a tearful goodbye to Fumiko and her mother, who were being taken away on a tram. Fumiko gave Steves her teddy bear.

Steves turned five later that year and he was distressed during his own birthday. “I didn’t know any white kids,” he says. “My mother invited a whole bunch of white kids and I refused to play with them. I walked out of my own birthday party. I had a First Nations friend that lived up the street and he played with me, the two of us alone, while the white kids had birthday cake. I guess it really must’ve affected me because I remember it very well.”

Battle for the basements

Canadians generally think of multiculturalism as having arrived after 1967, when the country opened its doors wide for immigration. Richmond in particular has become known as a paragon of that multiculturalism, with people of colour now comprising 80 per cent of the population. Most are Chinese residents of different backgrounds, followed by South Asian and Filipino residents.

But pre-war Steveston was already an early Canadian example of people from different parts of the world living together, a mix of white, Chinese, Japanese and Indigenous people. As a result, inclusivity remained important to Steves because, quite simply, “that was how I grew up.”

In 1976, institutional racism reared its head again in Richmond. It was a rare year that Steves was not in office, having finished his term as MLA, but he couldn’t catch a break. “We took the city to court!” he says.

There was an influx of immigration from India and many newcomers lived in basement suites as part of multi-generational households. Basement suites were illegal unless you had an inspection from the city, but it wasn’t a problem until there were complaints against the newcomers.

“The city basically declared them illegal and laid charges,” says Steves.

He recalls about 106 families charged, 103 of them South Asian. Steves’ friend, the late Bill Sigurgeirson, the one who ran the CCF meetings in his parents’ basement, had become a lawyer. So Steves asked him to defend the families in court. They argued that the newcomers should be considered part of the primary family due to their close ties.

The charges were dropped and the city eventually backed off because of a housing crisis. Because of his role, Sigurgeirson received racist phone calls and death threats. It wasn’t until 2000 that the city finally legalized basement suites.

“You’ve got to have a lot of patience,” says the politician after 50 years in office.

‘A strong consistent voice’

Garry Point Park. Terra Nova Rural Park. The Britannia Shipyards. The Garden City Lands.

These now-beloved Richmond projects passed through council between Steves’ re-election in 1977 and his retirement in 2022. With the population of Richmond growing from about 10,000 to 210,000 in his lifetime, Steves has always made an effort to keep the island city green. The farmer-councillor was especially pleased to see the Garden City Lands — a large piece of land near the downtown but untouched for years due to legal battles — host Kwantlen Polytechnic University’s Farm School. During his tenure, the city also established a municipal district energy corporation, became a regional leader in diking against river and coastal floods and hosted events in the 2010 Winter Olympics.

Richmond’s current mayor Malcolm Brodie, who was a two-time councillor before taking the top job for the first time in 2001, says he worked well with Steves, who agreed, having never felt the need to challenge Brodie for the mayor’s seat.

“He was a strong consistent voice,” says Brodie. “The passions he had and the directions he wanted to take, they didn’t change with the wind.” While Brodie is a self-described centrist and Steves a progressive, the mayor says they only had “little differences” over the years.

The two also served in regional governance with the Metro Vancouver district and politicians from other cities were often wowed by Steves.

“He has an amazing archive,” says Brodie. “He would find old reports and old procedures that would pertain sometimes the most obscure situation. The context for it shaped your thinking, then you had the benefit of hindsight.”

Does Brodie, with 26 years in office, think he’ll ever catch up to Steves’ record?

“Let’s just say I don’t consider it probable,” he says. “When you think about it, if a politician today was to be elected, and be in office for as long he was, you’d have that person beyond 2070.”

A Wolfe at the door

While Richmond’s council embarked on a number of entrepreneurial conservation projects, Steves worried that if he were to retire one day, there wouldn’t be someone in office that shared his same concern for the environment. As it turned out, there was someone in council chambers who did, though he was sitting on the other side of the table.

About two decades ago, Michael Wolfe, a university student studying biology, started showing up at every single meeting. It was pollution and wildlife that he cared most about, but he challenged himself to find something on each agenda to speak to every meeting.

“I wouldn’t just speak and leave,” says Wolfe. “I’d sit and listen to the discussions. Harold Steves had this authentic way of listening extremely well. He was most likely the person to respond to my presentation while most of council would just give you the blank stare.”

At UBC, Wolfe started attending Green Party meetings, where he met Adriane Carr, then the leader of the BC Greens. It was the kind of politics he wanted to see in Richmond, so he decided to run for the school board in 2005.

On the deadline to submit his nomination papers, Wolfe asked city staff how many people he was up against. They said 15.

“What about for mayor?” he asked.

They told him that only Brodie the incumbent was running for mayor.

“I said, OK, sure, I’ll run for mayor too.”

On the campaign trail, Wolfe had the opportunity to watch Steves closely as he won another election. One day they met up for beers at the Buck & Ear, the pub of the 137-year-old Steveston Hotel.

“He was saying how he saw this kind of fire in me, this passion that reminded him of himself,” says Wolfe. “He said, if you don’t get elected here, keep coming to council meetings, keep speaking, keep sharing perspectives because we need to hear it.”

Wolfe, who was 23 at the time, did not get elected. But he did keep going to council meetings, speaking his full five minutes every time. And when he took part in local advocacy, fighting against a jet fuel pipeline and for the preservation of greenspace at the Garden City Lands, he often found himself shoulder to shoulder with Steves, who’d show up too.

In 2018, after 10 attempts to run for three levels of government, Wolfe was finally elected to Richmond city council. The keen citizen became the keen councillor, who attended every meeting of every city committee, only ever missing three occasions, one of them “because my daughter was born,” says Wolfe.

In council, Wolfe sat beside Steves. “I learned a lot from him, but for one year only. The pandemic came in,” says Wolfe. “It was really unfortunate, but fortunate in the way that we didn’t need to talk: we already got each other, like we’re on the same wavelength already.”

In 2020, Steves announced that his current council term would be his last.

“For years, I said [Wolfe] was the person to take my place so I could retire,” says Steves.

Racking up 50 years on Richmond council, does this make Steves the longest-serving councillor in B.C.? Neither the Union of BC Municipalities nor CivicInfo BC have an official answer. They’ve been tracking municipal offices in recent decades, but beyond that, the majority of 20th-century records are kept in paper and spread out in city halls across the province. That being said, Steves was in office longer than Alice Maitland of Hazelton, the province’s longest serving mayor of 42 years, who spent five years on top of that as a councillor.

In 2022, Steves made his exit and Wolfe was re-elected.

“Thankfully I [was],” says Wolfe. “Otherwise, I would have been a big disappointment!”

On top of shared passions, the two have a lot in common. Both are fourth-generation Richmondites. Both are science teachers. Both come from farming families; Wolfe these days keeps bees and an urban garden.

While Richmond council hasn’t been without Steves for long, he’s always top of mind for Wolfe, who is, quite literally, stepping into Steves’ shoes.

“Sometimes, I wear cowboy boots,” says Wolfe. “People say I have the same style as him, that shaggy head of hair. I’ve had sideburns ever since I met him, so it’s probably where it all got started. I also wear plaid jackets like he does. So I’m kind of like this younger version of him. I always think of how well he listens…. If it wasn’t for him being there [for me], listening, asking questions, I probably would’ve called it quits a long time ago.”

Forget term limits!

Because of the pandemic, Kathy Steves had a preview of what it was like to have her husband around the house more often.

“I would prefer if he wasn’t in the house the whole time, 24 hours!” she says with a laugh.

The couple met during their time at UBC. Kathy was studying nuclear physics.

“I didn’t take physics in high school because girls just didn’t go into it,” says Kathy, but university offered her that opportunity. “I just loved it. Physics, you always know what was going to happen. It all worked out straight. I was comparing it with biology and the animals all seem to do something different.”

Like Steves, Kathy became a teacher as well. When they had children, she ended up staying home to raise them, working on the farm and tutoring at night. When her husband ran in his first election, she went through the phone book to contact voters. When Steves brought out an old report that impressed other politicians, it’s thanks to Kathy that the papers are organized and ready to whip out at a moment’s notice. In 2020, the couple celebrated their 60th anniversary.

“We’ve done everything together,” said Steves. “Basically, she’s kept me in order. She’s done all the filing, so now she’s doing the unfiling.”

As Steves’ political career began to wind down, the final years were filled with events that echoed back to his early years of activism.

There’s the matter of the BC NDP, a party Steves has a hard time recognizing.

“Basically, the environmental people left the party and it ended up being just a labour party rather than a combination,” says Steves, who’s disappointed by clear-cut logging and the decision to complete the Site C dam, which he saw unions push for firsthand at the party convention following the NDP’s 2017 victory

The leadership race this past fall was another sign of that, he says, which ended with the party’s executive council ousting climate activist Anjali Appadurai, claiming improper membership sign-ups. Steves had called her a “breath of fresh air,” even encouraging many of his friends who’ve ditched the party to sign up again to support her.

There’s the matter of persistent attempts by moneyed interests to nab agricultural land, half a century after the creation of the ALR.

Steves and others have been constantly fighting efforts to take farmland out of the reserve for residential and industrial development as well as attempts to use farmland for purposes other than farming, such as the building of “megamansions” and “pot bunkers” with concrete flooring.

“He’s been a great champion of the cause,” says Bob Williams, who was a cabinet minister in the Barrett government when Steves was MLA. “I’m overwhelmed by how [ALR] has stood out and been supported by the population… but money is money and it’s always attractive.”

And then there’s the matter of reconciliation. For one, Richmond doesn’t open meetings with a land acknowledgment. Mayor Brodie has said that this is because the city is in land disputes with two nations, one of them being Musqueam, and that a land acknowledgment might result in sweeping legal implications.

But late November, Coun. Wolfe proposed a motion to establish a Truth and Reconciliation policy for the city, which was approved unanimously, and could pave the way for land acknowledgments, which is already being done in Richmond schools.

Steves’ hope is that the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language names of the two villages that predate Steveston will be restored. There’s Kwayo7xw, meaning “bubbling water” due to the marsh gas there, which is at the location where Garry Point Park is today. His grandmother’s diary has some stories about the Steves’ relationships with them. The other spot is Kwlhayam, which means “place with driftwood logs on the beach,” a fishing village near what would be become the site of the Imperial Cannery.

With such business still underway, no wonder Steves continues to tune into council meetings.

“I get a chuckle when people say there should be term limits,” he says. “I decided that if we should have term limits, it should be 50 years. You’re not going to do things overnight.”

It’s plain to see that there’s still more for Steves to do.

But for now, his granddaughters are visiting. And the family is ready to sit down for lunch. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics, Environment, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: