The year was 2014, and Vision Vancouver was riding high. The party had just won its third consecutive election and continued to control city council under then-mayor Gregor Robertson.

This was B.C.’s “wild west” era of political fundraising, and a look at donations made to Vision for the 2014 election shows just how much money was thrown at parties from both corporations and unions: a total of $233,900 from the Canadian Union of Public Employees, which represents many city workers. Vision received $230,000 from restaurateur David Aisenstat and companies associated with him. Tens of thousands also rolled in from real estate developers, luxury car dealers, taxi and towing companies, engineering firms and other unions.

The problem with unlimited campaign donations is simple: politicians are supposed to work on behalf of all citizens, but when certain companies, unions and wealthy people have had a big hand in getting a local politician elected, there’s more perceived pressure to return the favour — by making decisions that benefit those donors.

After local and international media drew attention to B.C.’s anything-goes system, a new NDP government in Victoria introduced legislation in 2017 that banned union and corporate donations to municipal campaigns. The new rules also limited individual donations to $1,200.

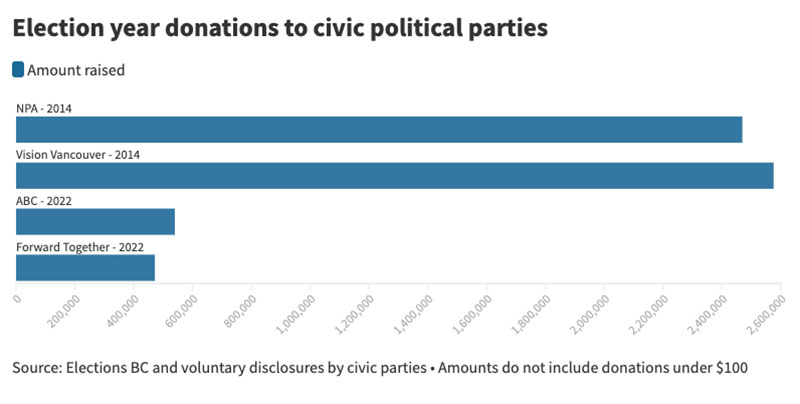

The Tyee compared 2014 donation totals reported by Elections BC and early donation disclosures made by Vancouver political parties for the 2022 civic election. The analysis shows that the new rules have dramatically lowered the amount civic parties can fundraise, but also shows that big money is still making its way into election fundraising. (Elections BC will release official data for the 2022 election in the next few months.)

In 2014, Vision Vancouver received 693 donations over $100, for a total of $2.5 million. Their rival party at the time, the Non-Partisan Association, received 868 donations over $100, for a total of $2.4 million.

In 2022, incumbent mayor Kennedy Stewart and his party, Forward Together, got 727 donations totalling $472,059. ABC Vancouver, the party that ended up sweeping city council, park board and the school board, received 665 donations and raised a total of $539,789. (None of these figures represent the total amount of donations parties had to work with in 2014 and 2022, but we’ve limited our analysis to just the donations received in each civic election year.)

After several elections run under the new rules, new patterns are emerging that show big money is still finding a way into the coffers of political campaigns. Similar trends have emerged in other provinces that capped donation amounts.

Duff Conacher, the co-founder of the watchdog group Democracy Watch, says these patterns show that B.C.’s new rules haven’t gone far enough.

“When you ban corporate and union donations, but still have a relatively high donation limit of $1,000 or more, it’s just a sham system that still allows big money to flow in and people to have undue influence,” Conacher said.

Conacher identified two ways wealthy people and corporations can work around donation limits. They’re called funnelling and bundling — here’s how they work.

Funnelling

When donations are funnelled, family members and company employees give individual donations that don’t exceed the donation limit. Together, those donations can equal the same amount the company used to give before the new rules came into play. It’s only illegal if the company reimburses the employees or family members for their donation.

Donation patterns seen in the 2022 disclosures show that some wealthy business people whose companies used to make significant donations to civic parties have now switched to donate as individuals — and their family members are donating the maximum amount as well.

In 2014, Aquilini Development and Construction gave a total of $60,000 to Vision Vancouver; Francesco Aquilini is listed as one of the directors of the corporation.

In 2022, Francesco Aquilini gave $1,250 to Mayor Kennedy Stewart’s Forward Together party — as did eight other donors with the same last name.

The same pattern can be seen for other major real estate companies that are run as family businesses. Amacon is a real estate company founded and run by the De Cotiis family, and nine people with the last name De Cotiis donated $1,250 each to Stewart’s campaign. Colin Bosa of Bosa Development, and seven other people with the same last name, donated $1,250 each to a rival party, ABC Vancouver. Lululemon founder Chip Wilson, his wife and his four sons — two of whom are still teenagers — also donated $1,250 each to ABC.

The Tyee is not suggesting that any of the donations described violated B.C.’s election rules.

Funnelling can fly under the radar when family members don’t share the same last name, or when the donations are coming from unrelated employees.

“All it does is obscured that big money flowing,” Conacher said. “It doesn't actually stop it. So it was actually easier before to say, ‘Oh, this corporation gave $20,000.’ And now you have to try and track down, who are these people, are they connected to this business?”

Quebec limited individual donation amounts to $2,000 back in the 1970s. But Conacher said that when the government of Quebec audited five years of election donations in 2011, auditors discovered $12.8 million of donations that had likely been illegally funnelled.

Without a whistleblower coming forward, it’s nearly impossible to prove that illegal funnelling is occurring. Thanks to a whistleblower, SNC-Lavalin is the only Canadian company to have been found to have violated the Canada Elections Act by funnelling donations through executives and their family members; the company entered into a compliance agreement with Elections Canada in 2016.

Bundling

Bundling is a term that describes the practice of organizing a fundraiser for a political party. It’s legal, but Conacher said it can still lead to the star fundraiser being able to wield influence over a politician or a political party.

“You have a party where a bunch of people come who each donate $1,000, and then you let the party know it was my party that recruited all these people,” Conacher said.

During the Vancouver civic election, a spreadsheet that was found on the sidewalk pointed to Stewart’s party, Forward Together, making a similar fundraising attempt, although many of the people named on the list denied they had ever agreed to act as fundraising “captains.”

One of the people named on that list, Francesco Aquilini, did sign his name to fundraising emails that invited people to a luncheon with Stewart. Donors who paid the maximum donation of $1,250 were promised access to a “pre-reception” event.

Conacher shared an example from federal politics. “The Liberal party has this thing called the Laurier Club,” he said. “If you donate near the maximum amount, which is now $1,675 a year, then you get invited to special parties where the leader and cabinet ministers show up.

“You're essentially buying access.”

Both examples are classic “pay to play” fundraising, a type of political fundraising that’s very common in B.C. politics and has been criticized for putting a price on access to politicians.

Conacher said he'd like to see provinces follow Quebec’s lead and lower individual donations to $100 a year, or $200 in years when a general election or byelection occurs. The province made the move after the Charbonneau Commission revealed extensive political corruption in the province, including outright bribery, around the awarding of municipal and provincial construction contracts.

“In Quebec, if you donate more than $50, you actually have to send it to Élections Québec and they verify that it's your money before they pass it on [to] a party,” Conacher said.

“That's how far they've gone in Quebec and they're the model for Canada.”

A $100 cap would dramatically reduce the amount civic parties could raise to run campaigns. In 2014, Vision Vancouver’s donations of $100 or under totalled just $138,110. COPE, a left-wing party that mostly relies on similar-sized donations, raised around the same amount in 2022: $104,319.

That budget would leave fewer dollars for ad buys, lawn signs and co-ordinated jackets — but it could level the playing field. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: