“I ended up here because I got lost! Honest.”

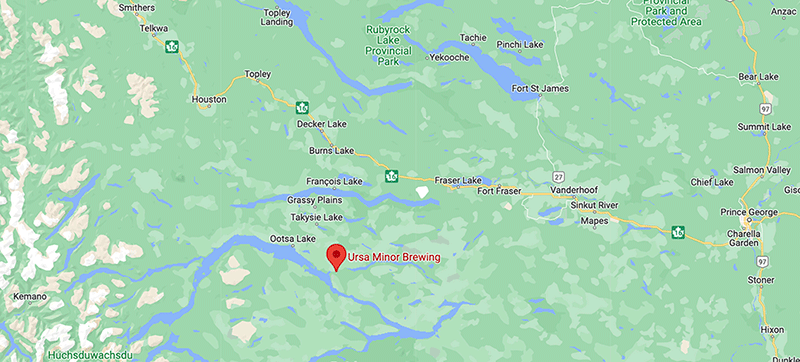

I’m skeptical. The entry, scribbled in the guestbook at Ursa Minor Brewing, is surprising given its location 100 kilometres down a labyrinth of resource roads south of Burns Lake, B.C.

The craft brewery seems like an unlikely — if fortunate — place to just stumble upon.

Indeed, owner Nathan Nicholas says day-trippers will dedicate hours to drive from northern communities like Smithers, Terrace and Vanderhoof just to sit near the placid inlet on Ootsa Lake and sip some local brew.

Industry workers have ventured here looking for something to do on a day off. Local cabin owners are grateful for a nearby venue to gather with neighbours, and campers looking for a hot meal and cool beverage are also enthusiastic guests. The guestbook even includes international visitors.

But it’s also true, Nicholas confirms, that the brewery gets the odd road-weary traveller who has taken a wrong turn.

That’s all part of the appeal, he says.

“We really want to have a destination brewery,” he tells me. “We want to be a tourist attraction.”

I arrived here very much on purpose, having driven 240 kilometres east from my home in Smithers, south from Burns Lake, crossing Francois Lake by ferry and continuing on through the small communities that dot Southside, the gently rolling, pastoral region between Francois and Ootsa lakes.

Here to research an article about the area’s history for The Tyee, I’m grateful for a glass of Siberian Express Haskap Saison and a dry place to work on this damp mid-July afternoon.

While Nicholas insists Ursa Minor isn’t the most remote brewery in the world (he references one in Norway and another in Iqaluit) it strikes me as unique that pretty much the only thing I can buy with my credit card within a 50-kilometre radius on this day — save some Ursa Minor swag — is beer.

Nicholas, also the operation’s brewer, grew up on this 540-acre property. His parents bought the land in the late 1950s after being displaced from their original home when Ootsa Lake was flooded by the Aluminum Co. of Canada, now Rio Tinto Alcan, to create the Nechako Reservoir that powers the mining giant’s smelter in Kitimat.

Nicholas left to pursue a culinary career and later worked in forestry. But he and his partner Gwyn moved back in 2018 determined to start a family business that incorporates the local culture of this remote area.

So it’s not surprising that the brewery has a special focus on local ingredients. The haskap berries in the saison I’m sipping were sourced from a nearby farm. Spruce tips for a session ale are plucked from local trees. Rhubarb from the Nicholas’s garden adds pucker to a pale ale.

Nicholas has even attempted a cottonwood beer (it was far too bitter, but he’s not giving up) and is considering a soopolallie, or soapberry, brew. Homemade soda and spruce-tip iced tea provide non-alcoholic options.

“It’s a really nice way to engage with people,” Nicholas says about purchasing ingredients from his neighbours. “That’s one thing we really wanted to do with our brewery is foster that sense of community again.”

Nicholas remembers a time when Southside thrived with small sawmills and family farms. But corporate industry made the operations uneconomical and many families left. He and Gwyn both attended a nearby elementary school, which has since closed. The changes left the community fractured — well before the pandemic came along.

As they worked toward opening the brewery in 2018, the Nicholases battled an epic wildfire season, which delayed Ursa Minor’s opening until June 2020. Today, it offers COVID-19-friendly outdoor picnic tables and a place for people to come together again.

The brewery operates during the summer months. On this rainy Thursday afternoon, its tasting room is open by appointment only. It has regular business hours Friday to Sunday, and most weekends the former chef fires up two large barbecues. Be sure to book ahead to guarantee your dinner, Nicholas warns.

Other than beer and a hot meal, perhaps the most important thing a remote brewery needs is a place to pitch a tent. The couple is working on that. On Aug. 1, they plan to open a small campground that will host visitors who want to spend more time in this peaceful location, where swallows swoop and loons call, hours from the nearest city.

“Sometimes I wonder if people come for the beer or to see the crazy people who started a craft brewery in the middle of nowhere,” Nicholas jokes. ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: