This story was produced in partnership with fellows of the Global Reporting Program at the University of British Columbia's School of Journalism, Writing and Media. View additional project credits.

On Jan. 4, 2020, as news began to spread about a novel coronavirus, Hereditary Chiefs from the Wet’suwet’en Nation felled trees across a snowy resource road and evicted the company that intended to build a pipeline through their traditional territory.

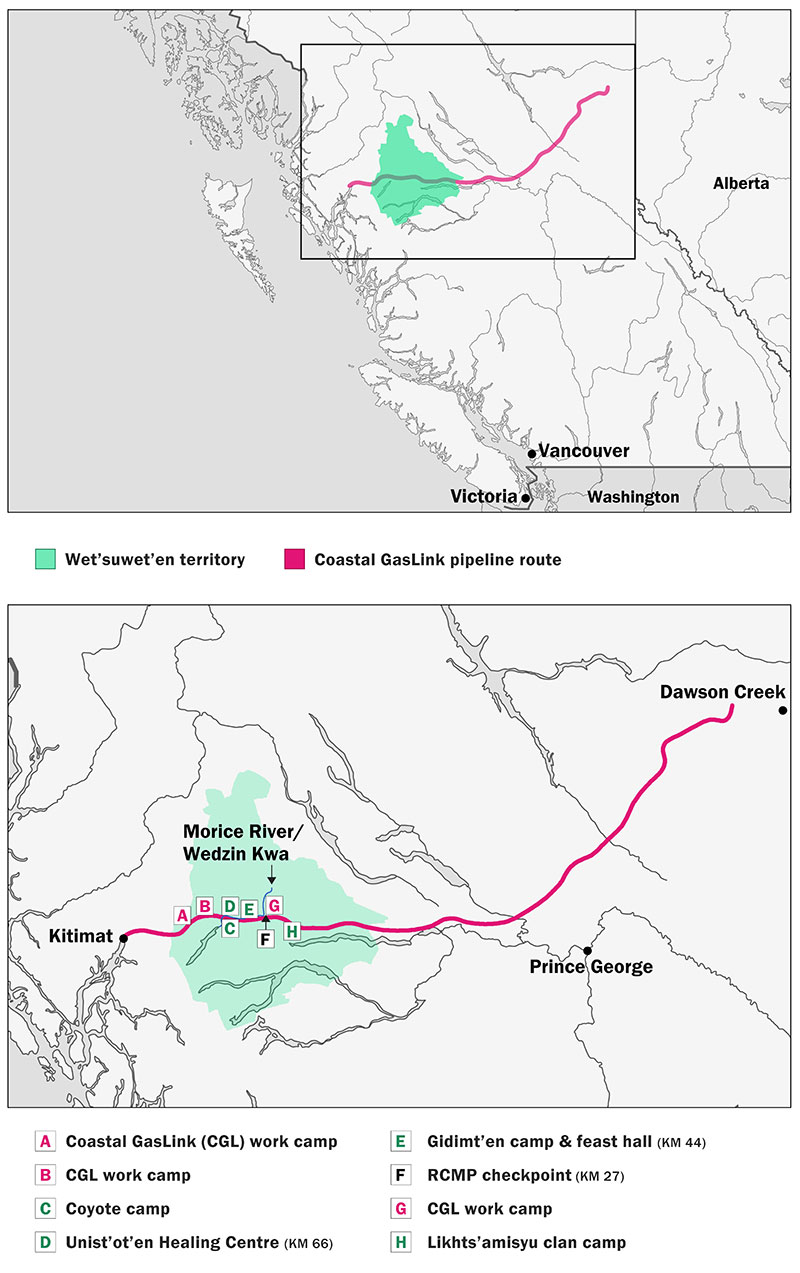

The Chiefs were responding to an injunction, issued days earlier by the B.C. Supreme Court, that allowed police to arrest anyone blocking access to Calgary-based TC Energy’s 670-kilometre Coastal GasLink pipeline, currently under construction from northeast B.C. to an LNG processing plant on the coast in Kitimat. Roughly a quarter of the pipeline route crosses Wet’suwet’en territory and the project has faced long-standing opposition from the nation’s traditional leadership.

A month-long standoff began.

By early February, the crisis in remote northern B.C. was vying with COVID-19 for national news headlines as protests expressing solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en shut down highways and shipping routes across the country. On Feb. 10, after a five-day enforcement and 28 arrests, heavy machinery pushed aside the remaining month-long accumulation of snow from the Morice Forest Service Road, clearing the way for industry.

Then, it went quiet.

In the weeks that followed, the Hereditary Chiefs went into talks with the provincial and federal governments, by late February reaching an agreement to resume negotiations over Wet’suwet’en land title. Days later, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. Then B.C. declared a state of emergency. Wet’suwet’en communities went into strict lockdown.

“Everything just stopped,” says Molly Wickham, a member of the Gidimt’en Clan who holds the hereditary name Sleydo’. She lives on the territory not far from the pipeline route and says while the camps remained, no one came or went.

“We basically just shut down for more than a year. I felt like we were paralyzed,” she says. “It was a way for them to do the work without any Wet’suwet’en resistance and without any eyes on the significant increase in work.”

As communities locked down, the B.C. government took steps to ensure the economy kept moving. Large industrial projects like Coastal GasLink were quickly declared essential services and camp-style accommodations were permitted to continue hosting hundreds of workers.

The move, some argued, was an opportunistic claim to Wet’suwet’en territory, fitting the definition of a disaster land grab: a moment when calamity — whether storm, earthquake or disease — makes it easier for powerful interests to impose their will on local populations under intensified duress.

“To the extent that this is Indigenous land, it is a land grab, because it is using a disaster to attempt to override the assertion of Indigenous rights and titles,” says Canadian journalist and author Naomi Klein, who recently became an associate professor of climate justice at the University of British Columbia. “I think it’s fair to say that the B.C. government has taken full advantage of the pandemic to push through projects that are dividing Indigenous communities, that are highly contested, that have been the subject of mass demonstrations in B.C. and across Canada.”

B.C. wasn’t alone. In July 2020, as the world’s attention was on the unfolding COVID-19 crisis, the Ontario government pushed through an omnibus bill that significantly weakened environmental assessment laws. Alberta’s government also eyed pandemic upheaval as an opportunity to push oil and gas development through the unceded Indigenous territories of B.C. to reach overseas markets.

“Now’s a great time to be building a pipeline because you can’t have protests,” Alberta Energy Minister Sonya Savage said in a May 2020 interview, where she referred to “fringe radical left” and “nutbars” opposing fossil fuel development.

“So, let’s get it built.”

Defining disaster land grabs

The term land grab provides a loose definition for the practice of governments paving the way for industry by handing over communally held parcels of land for economic development.

At times eschewed by academics, the phrase is as blunt as the image it depicts. But its directness serves a purpose, says Sam Szoke-Burke, a senior legal researcher for the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment: “It’s just a bit more accessible,” he says. “It’s blunt, but the bluntness allows us to reach more people using it.”

While use of the term “land grab” can be traced back decades, it became widespread in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and overlapping world food crisis, as land speculation took hold in places like Africa, seen to have large tracts of land at low cost.

Klein’s 2007 book The Shock Doctrine, in which she coined the term “disaster capitalism,” examines shock therapy treatments used in the mid-20th century and interrogation tactics adopted by the CIA — things like sleep deprivation, fear and isolation — all designed to clear existing ideas and replace them with new ones. She draws parallels to how the shock of disaster can be used to override economic policies and clear land for development.

Disasters were frequently the lever that powerful interests used to separate the people from the land.

“Opportunistic governments might have less scrutiny or counterweights from civil society or even from their own regulators, and that’s where rights of local communities can be more quickly thrown under the bus,” Szoke-Burke says. “Land grabs can more easily occur in one way or another.”

That’s what happened at different times in Liberia, the Philippines and Caribbean island of Barbuda, their stories told via historical timelines in sidebars throughout this article. The interactive globe below has further examples.

Examples of Land Conflicts Around the World

Visualization made with globe.gl using imagery from NASA's Visible Earth.

In short, experts say these elements are common to disaster land grabs:

- A destabilizing factor, such as a natural disaster or disease

- Land that is often communally owned or Indigenous territory

- Limited ability for communities to engage with each other or decision-makers

- Implementation of policies, authorizations or land sales to further economic interests

- Displacement of occupants based on those legal or policy decisions

So does the disaster land grab paradigm apply to the construction of a gas pipeline through territory of First Nations never formally ceded to the governments of British Columbia or Canada by its long-time Indigenous inhabitants? That complex question requires revisiting events stretching back long before the Coastal GasLink project was conceived or the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus materialized.

“Colonialism was a land grab,” says Haroon Akram-Lodhi, a professor at Trent University’s department of international development studies. “That’s true whether we’re talking about the Americas, whether we’re talking about Africa, whether we’re talking about Asia. We’ve basically been living in a world where land grabbing has been central to economic processes for over five centuries.”

Akram-Lodhi describes “a process of continual enclosure,” or taking what was held communally and privatizing it for profit, dating as far back as 16th century Europe that continues today in Canada’s resource-based economy. “The thing about resource extraction, of course, is that in Canada resource extractions take place on Indigenous territories,” he adds.

While the Royal Proclamation of 1763 clearly stated that all lands not ceded or sold to British interests remained in the hands of Indigenous peoples, what followed in Canada was a slow creep of dispossession, with industry used as the tool to push colonial interests across Indigenous land.

The pattern dates as far back as the introduction of the Hudson's Bay Co. and Canadian National Railway, says Shiri Pasternak, assistant professor of criminology at Toronto Metropolitan University. Today, it continues with the Coastal GasLink pipeline, she adds.

“There’s an interesting parallel, I think, that you can draw in terms of how the land grab with Coastal GasLink happened and how earlier land grabs happened, involving this trifecta of companies, governments and the police, which is that corporations have always been really integral in Canada to extending Canadian sovereignty,” Pasternak says.

“It’s the advancement of the company’s property rights that were recognized in the courts, and that enable the whole mechanism of police enforcement to go in and violently remove people where the state actually couldn’t exercise that.”

Increasingly, the court system has been used against Indigenous nations opposing industry by issuing injunctions that favour corporations over the people who might stand in their way, says Estair Van Wagner, an associate professor at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School.

Van Wagner is part of a group of academics working to unravel the legal history of the Great Land Grab, the dispossession of Hul’qumi’num territory on Vancouver Island where land was originally handed over for railway development, then transferred to forestry companies and, more recently, investment firms who sold it to Canadian pension funds.

As a result, the nation may never lay claim to 80 per cent of its territory that was first handed over to industry in the late 1800s. Like on Wet’suwet’en territory, watersheds and sacred sites have been impacted and gates prevent access to some areas of the territory.

But as layers of interests in the land accumulate over time, Van Wagner describes how the courts skew their weighting in favour of authorizations granted relatively recently to industry over the long-standing and continuous use of First Nations.

In the case of the Wet’suwet’en, claim to the land has also been affirmed by Canada’s highest court.

“The Wet’suwet’en have a very strong interest in that land, akin to the strongest that you could make in Canadian law,” she says. “It’s a good example of how these presumptions and biases work their way into the supposedly neutral processes of the court.”

Since time immemorial

Two years after the World Health Organization declared the pandemic, on a March overcast day, Chief Na’Moks stands at the confluence of the Bulkley and the Skeena rivers. On his left, the Bulkley flows from the Morice, recognized by the Wet’suwet’en Nation as one river, Wedzin Kwa, its headwaters deep in the nation’s traditional territory. To his right, the Skeena flows through Gitxsan territory, an Indigenous nation whose identity is embedded in the river’s traditional name: Xsan.

They join here under the commanding presence of Hagwilget Peak, Stegyawden, flowing together just as the two neighbouring First Nations have since time immemorial — that is, longer than anyone can remember.

“We have such a deep connection to the land,” Na’Moks says. “How could you feel mad, alone, frustrated, defeated when we’re standing right here, where both those powerful nations become one?”

Na’Moks’ ancestors stewarded these territories for millennia. He was born John Ridsdale, his father Gitxsan and his mother Wet’suwet’en. The cultures are matrilineal, so he carries his mother’s Wet’suwet’en heritage and the hereditary name Na’Moks, which once belonged to his maternal grandmother. It puts him amongst the nation’s highest-ranking Chiefs.

The names are earned, passed down after years of learning the culture. They are both a privilege and a responsibility. In addition to honouring the ancestors who held the name before him, Na’Moks is tasked with upholding the title and preserving the culture for those who will come after. Inextricably tied to that is protecting the land.

That has become harder in the time of COVID.

Na’Moks lives in the nearby village of Hagwilget, a joint Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en community that embodies the two nations’ historic relationship of co-operation. Hagwilget was among the first Indigenous communities in the region that locked down when the pandemic hit, imposing 24-hour security, monitoring residents’ movements and taking their temperatures when they returned to the village. Visiting was prohibited, even between neighbours.

The village is managed by one of six Wet’suwet’en elected councils and is the only one that didn’t sign an agreement with Coastal GasLink. The nation’s remaining five band councils — which sit closer to the pipeline route but don’t overlap its path — agreed to a portion of pipeline profits through benefits agreements, which are frequently touted as evidence of support for the project.

But it was Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en traditional leadership, the Hereditary Chiefs, who jointly fought the Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa court case, a decade-long effort that ended in 1997 with the Supreme Court of Canada acknowledging on appeal that the nations had never ceded, or relinquished, title to their traditional territories.

Traditional Wet’suwet’en travel routes crisscross Coastal GasLink’s pipeline corridor. There was a village site at the confluence of Wedzin Kwa and Lamprey Creek, known to the nation as Tsel Kiy Kwa, near where Gidimt’en Camp — the site of several police actions — now stands. On a ridge above the camp, an archeological site was destroyed last summer by Coastal GasLink under the authority of BC Oil and Gas Commission, as it stood in the way of pipeline construction.

Wet’suwet’en ancestors would travel these routes from permanent homes on the territory to seasonal fishing villages in communities like Witset, where salmon congregate on their annual spawning journey. Here, they would fish and feast, joining gathering with governance, as they caught and preserved food for winter.

As Europeans moved into the area in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Wet’suwet’en increasingly returned home to find their cabins had been burned or taken over by settlers, says Chief Dsta’Hyl of the Likhts’amisyu Clan, whose English name is Adam Gagnon.

“Over the years, the government slowly burned all of the homesteads out,” he says. “The government was trying to force them onto reserve, into a complete entitlement situation there, so that they could have the extraction industries just steal all the resources off the land.”

Land reoccupied

When Wet’suwet’en began building cabins on traditional clan territories in the 1990s, it was a deliberate move to reoccupy the land, Dsta’Hyl says.

“It was to try to get our people out of the entitlement situation that they were forced into by the federal government back in the 1800s right through to the 1950s,” he says. “The camps are basically to start educating the younger generations.”

Some encampments have also coincided with pipeline opposition, strategically positioned near the project right-of-way or access roads.

In 2009, several years before Coastal GasLink was proposed, the Unist’ot’en, a Wet’suwet’en house group, began building a healing centre on its territory next to Wedzin Kwa. It installed a gate on a bridge over the river to keep out the crews that came to scout for future pipelines.

At the time, two pipelines were proposed for Wet’suwet’en territory — Enbridge’s Northern Gateway bitumen pipeline and Chevron’s Pacific Trails natural gas pipeline, which was recently purchased by Enbridge. The Office of the Wet’suwet’en, which represents the hereditary leadership, spoke to The Tyee in 2008 about its concern that the proposals could open the door to further pipeline development.

A decade later, despite its inability to access a portion of the route, Coastal GasLink had been granted an environmental certificate by the B.C. government and was becoming anxious to access its pipeline route through Unist’ot’en territory. The B.C. Supreme Court issued an interim injunction barring anyone from blocking access to pipeline worksites or access roads.

Gidimt’en Clan, which shares a boundary with Unist’ot’en at Wedzin Kwa, responded by building its own camp near the pipeline route.

On Jan. 7. 2019, 14 people were arrested for blocking the road at Gidimt’en Camp in what would become the first of several police actions on the territory. While Unist’ot’en would agree to allow access while the matter remained before the court, on Dec. 31, 2019, the B.C. Supreme Court granted a permanent injunction for the duration of pipeline construction, leading to the standoff in early 2020.

As the pandemic took hold and the fight for land sovereignty returned to the negotiating table, things quieted on the territory — but they remained unresolved. In September 2021, citing the authority of Gidimt’en Hereditary Chief Woos, Wet’suwet’en and supporters occupied a strategic Coastal GasLink worksite where the company plans to drill under Wedzin Kwa. Dubbed Coyote Camp, it became the site of a third police action in November.

At a bail hearing days after the November arrests, Coastal GasLink lawyer Kevin O’Callaghan argued that the reoccupation camps did not constitute communities. “There is no such village or town within the area covered by the injunction,” he said.

The argument isn’t new. A version of it is 600 years old, in fact, in the form of the much-maligned Doctrine of Discovery, a legal concept based on two 15th century papal bulls used to justify the colonization of “undiscovered” land on behalf of European nations. The doctrine is based on the premise of terra nullius — land belonging to no one.

As Wet’suwet’en land defenders transitioned from protest to pandemic in early 2020, it may have again appeared the territory was deserted. The camps remained quiet, with few coming or going.

Despite a condition by Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs that RCMP leave the territory before negotiations could begin with the federal and provincial governments, police continued to patrol and work on the pipeline resumed, with work camps housing hundreds of transient workers.

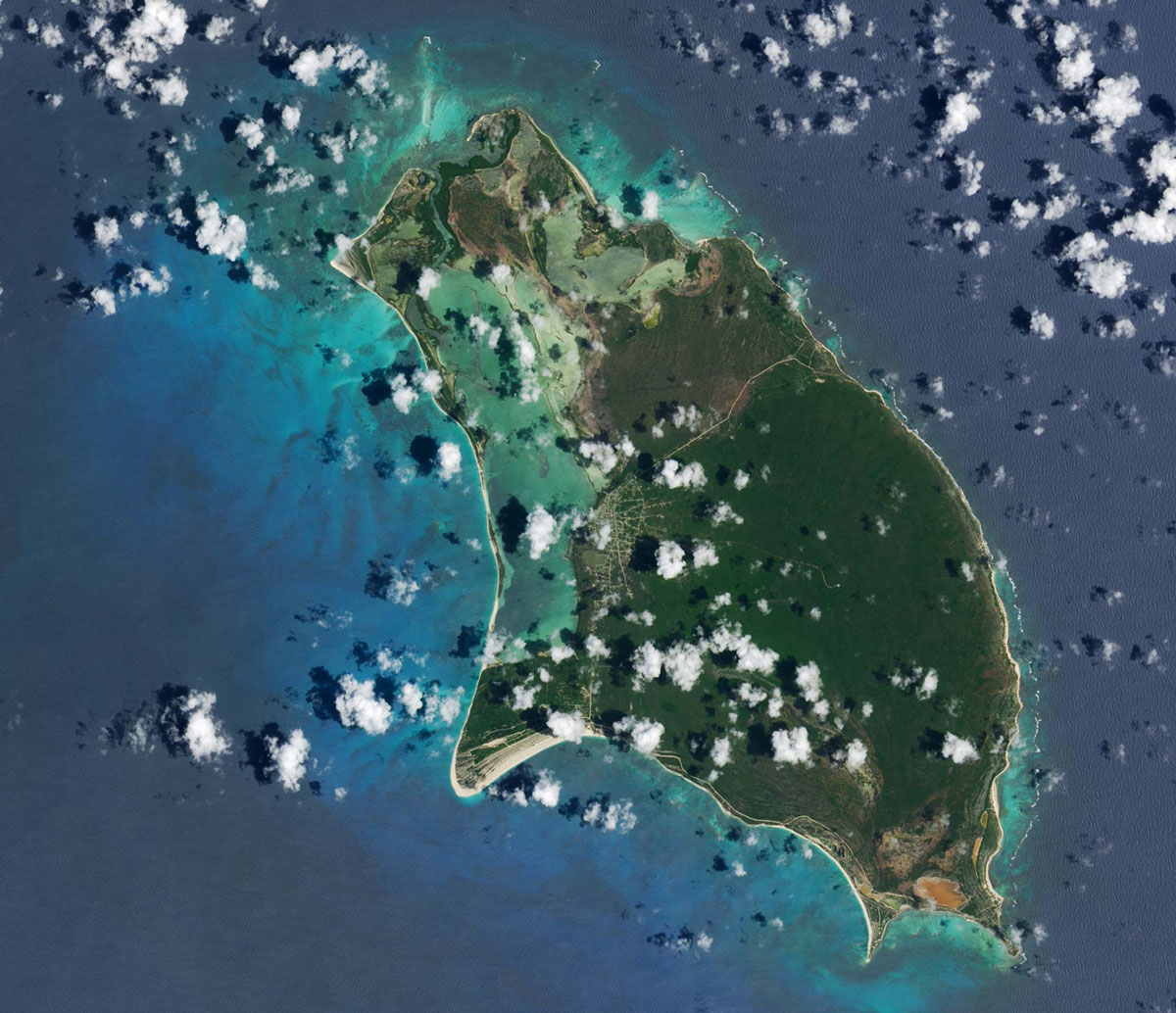

Aug. 27, 2017

Aug. 27, 2017

Sept. 12, 2017

Sept. 12, 2017

Disaster Land Grab in Barbuda

In 2017, Hurricane Irma levelled the island of Barbuda. Ninety-five per cent of buildings were damaged or destroyed, communications and power went down, and access to water was cut off. In the following days the entire population of the island was evacuated to the sister island of Antigua.

Antigua — the more developed and populous of the two islands that make up the nation of Antigua and Barbuda — is the economic and political centre. Today, it’s home to roughly 99 per cent of the country’s population.

Costs for rebuilding Barbuda were estimated at up to US$220 million (C$281 million). Prime Minister Gaston Browne made it clear that Antigua should not foot the bill for recovery, indicating that Barbuda’s land policies limiting privatization were a reason.

In 2007 Barbuda passed an act declaring that all its land “shall be held in common by the people of Barbuda.”

“You cannot tell us that you do not want any development and then come to us, the Antiguan treasury, for a cheque on a monthly basis,” Browne said in a 2018 interview with Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Even before Irma barrelled across the Caribbean, Browne had been pushing for a major resort on Barbuda, drawing criticism from land rights advocates.

Despite repeated attempts, representatives from the prime minister’s office and the Department of Environment for Antigua and Barbuda did not respond to requests for comment.

“The human rights violations, ecological destruction, disaster capitalism, it's all happening on this tiny island,” said Jasmine Rayée, a legal officer at the Global Legal Action Network, or GLAN. Rayee sees Barbuda as a microcosm of the problems facing the wider Caribbean, and potentially the world.

“It's not land grabbing in the sense of, “I get there with bulldozers and I keep people out,” said Tomaso Ferrando, a consultant and pro-bono advocate for GLAN, “but it’s how through legislation and abuse of power you guarantee that… hundreds of acres of land can be privatized.”

“Gaston Browne had been trying to get control of Barbuda land for a very long time,” said Claire Frank, writer and founder of the local news site Barbudaful. “And the hurricane helped him do this.”

Here’s how it played out.

Timeline

The Barbuda Land Act is introduced. The act states, “All land in Barbuda shall be held in common by the people of Barbuda,” and “No land in Barbuda shall be sold.” It codified the Barbudans’ communal land practices established following the abolition of slavery in 1834.

Prime Minister Gaston Browne announces a development project called Paradise Found — a business venture to build a US$250 million (C$313 million) resort on Barbuda with funding from actor Robert De Niro and investor James Packer.

The Paradise Found Project Bill is fast-tracked through approvals. The bill supersedes certain sections of the 2007 Barbuda Land Act to make conditions for development more favourable.

When people described the COVID pandemic as “unprecedented,” a number of Indigenous voices pointed to the grim precedent that haunted their collective memories — the devastation wrought by the 1862 smallpox epidemic first transmitted by Europeans. “It was frustrating, but it was also terrifying, because nobody really knew the extent to which COVID would impact our communities. We did know that bringing people into our communities from outside was a huge risk, particularly to our language speakers and our vulnerable people,” Sleydo’ says. “It was a really stark indication of where their priorities were.”

By late March 2020, the province had declared the pipeline and other large construction projects in the north — like the corresponding LNG Canada plant and Site C dam — to be essential services, or those “essential to preserving life, health, public safety and basic societal functioning,” according to a March 26 statement by the province.

Some expressed concern over the designation.

The Union of BC Indian Chiefs wrote an open letter calling for an immediate halt to pipeline construction, saying “the risks posed by continued work on the Coastal GasLink project are ones that were not consented to and ones that leaders and officials raised warnings about in advance of the project’s approval.”

Former chief medical health officer for B.C.’s Northern Health Authority, David Bowering, also called on the province to close the camps, naming them “COVID-19 incubators” that heightened the risk for workers and local communities.

Even B.C.’s then-deputy minister of energy, mines and petroleum resources Dave Nikolejsin quietly expressed misgivings, saying in an internal email later revealed by the CBC, “I can’t argue Site C, LNG Canada, etc. are essential.”

As pressure mounted to close the camps, Coastal GasLink initially fell back on seasonal workforce fluctuations. It was the cusp of spring thaw, when access roads become impassable and industrial work takes a breather. The company announced it was sending workers home.

“With spring breakup around the corner, we expect a significantly slighter workforce to be onsite to perform critical tasks,” it said, promising enhanced COVID-19 measures and a workforce reduced from 1,200 in February to about 400 by mid-March.

But by late summer, construction was back in full swing, with nearly 3,000 workers employed along the pipeline route, and by December local communities were beginning to experience the effects. Witset began to see COVID-19 spread in the community, brought by those travelling between home and work camps.

Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs called on the province to close the camps. “We understand that the province has declared oil and gas work an essential service, however, we strongly encourage you to reconsider,” the Chiefs wrote in a letter to B.C. provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry. “The economy cannot come before Indigenous lives.”

Days later, Northern Health Authority declared a COVID-19 outbreak at two work camps for Coastal GasLink. Workers were sent home for the holidays. In the new year, a public health order enforced a phased return to work in the early months of 2021.

Pipeline construction in a pandemic

TC Energy declined interview requests for this article and didn’t respond to questions about how the pandemic had affected project timelines.

A spokesperson for the company instead said in an email that “the health and safety of our workers, their families and Indigenous and local communities has and continues to be our first priority.” The company underscored its work with provincial health authorities and medical services providers to implement safety protocols during the pandemic.

“As the situation changed we continued to evolve our plans for effectiveness and implement improvement as necessary through testing and vaccination,” it said, citing access to project-wide vaccinations and testing beginning in February 2021.

However, the company has blamed the restrictions imposed in early 2021 for delaying the project and causing significant cost overruns that have led to friction with LNG Canada, saying in its 2021 annual report that, “Coastal GasLink is in dispute with LNG Canada with respect to the recognition of certain costs and the impacts on schedule.”

Monthly updates issued by the company indicate that protests in Wet’suwet’en territory may also have put the project behind schedule, with work in that section lagging behind the rest of the route.

While in some parts of the world the pandemic was used to avoid consultation and push projects through — Szoke-Burke points to examples in the Philippines, Liberia and Colombia — the B.C. government says that consultation with First Nations didn’t slow, with discussions moving online and continuing “at typical levels.”

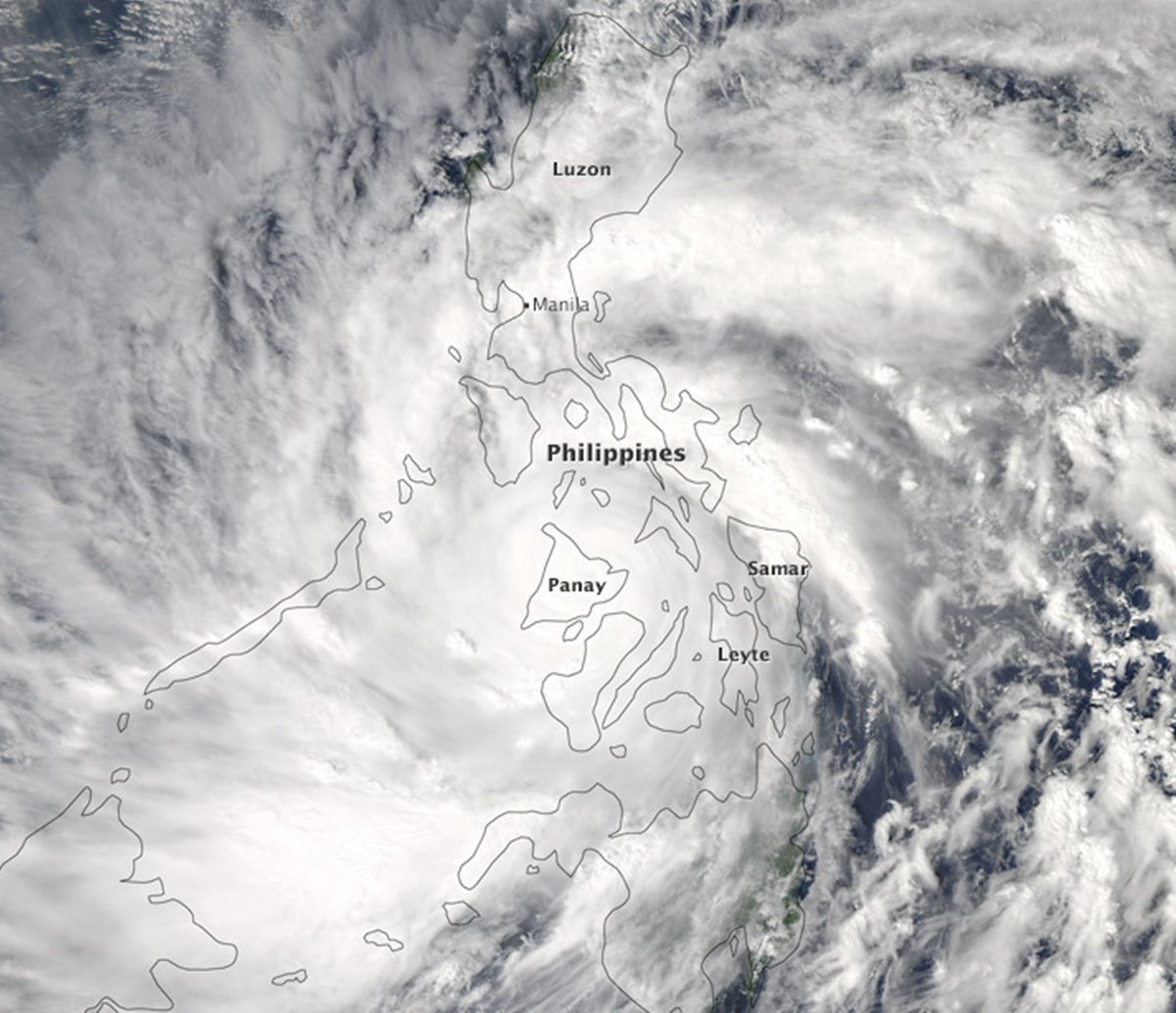

Nov. 7, 2013

Nov. 7, 2013

Nov. 8, 2013

Nov. 8, 2013

Disaster Land Grab in the Philippines

Village Chief Wenefred Gonzales remembers how the gusting winds and torrential rain tore apart his home in 2013. Houses on tiny Sicogon Island, part of the Philippines, came crashing down from the intensity of Super Typhoon Haiyan.

In the aftermath of the massive tropical storm, the government turned to the private sector to bolster rebuilding and recovery efforts. Ayala Land, Inc. or ALI, a subsidiary of Ayala Corp., one of the archipelago’s oldest and largest conglomerates, focused its investment on Sicogon Island.

With white sand beaches and turquoise waters, this dot in the Indian Ocean is almost entirely owned by the Sarrosa family, through their company Sicogon Island Development Corp., or SIDECO. Post-Haiyan, SIDECO partnered with ALI to rebuild the island as a world-class tourist destination.

Meanwhile, Gonzales says families were barred by SIDECO security guards from rebuilding or even repairing their damaged homes. He adds that residents were harassed, with security deployed along the shore to block the arrival of assistance like food and construction supplies. ALI and SIDECO also gave residents options for post-Haiyan resettlement, which would require people to give up their land claims and leave the island.

ALI and SIDECO declined to be interviewed, but in an emailed response, a representative of the ALI-SIDECO joint venture SITEC said, “There was never any attempt by SITEC to prevent assistance nor cause any harassment of residents on the island.”

Here’s the timeline.

Timeline

Residents have been locked in a years-long dispute with the Sarrosa family and its firm to secure land rights for farming and fishing. Residents allege ongoing intimidation, violence and threats from members of the family.

A government notice is issued slating 335 hectares of SIDECO-owned land for redistribution to some island residents. The notice, from the Department of Agrarian Reform, or DAR, falls under an act put in place to grant communities’ land rights for farming and fishing. The act allows for the redistribution of both public and private land to farmers.

SIDECO and ALI break ground on a multimillion-dollar development. Looking to build a new tourism industry, the plan includes a five-star luxury resort, a seaport and an airport. Sicogon residents protest the development, which will include the 335 hectares of disputed land.

In an email, the Ministry of Environment adds that a lack of project approvals, with the province failing to grant a single environmental certificate in 2020 and 2021, is not pandemic-related. Instead, it blames natural fluctuations in the permitting process — despite granting an average five, and at minimum two, certificates a year in the decade leading up to the pandemic.

There are also indications that some pandemic measures may have disproportionately benefited the oil and gas industry.

According to U.K.-based environmental journalist Fred Pearce, author of The Land Grabbers, as governments struggled to find their footing early in the pandemic, the uncertainty offered opportunities for corporations to successfully argue that economic recovery depended on their projects continuing.

“People are very flexible about coming up with excuses to do things, but certainly in non-normal times, it becomes a lot easier to make plausible excuses,” he says. “A lot of people made a lot of money out of the pandemic.”

A report by Statistics Canada that analyzed the pandemic’s impact on productivity growth indicates that companies considered essential during the pandemic benefited in particular. While the GDP contribution of the arts and entertainment sector plummeted by 47 per cent in 2020, mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction collectively dipped by less than five per cent.

The findings, the report concluded, were “a result of the structural changes during the pandemic towards industries that carry out a larger share of essential activities.”

In addition to being declared an essential service, pandemic relief also flowed to the oil and gas sector. According to Canada’s National Observer, the federal government provided more than $1.3 billion to the industry in the first seven months of the pandemic through the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy.

At the same time the industry was fuelling up on wage subsidies, it continued to raise dividends and provide large bonuses to company executives.

Canadian banks have also continued to invest heavily in fossil fuels during the pandemic. The country’s five biggest banks increased fossil fuel financing by 70 per cent, or around $61 billion, last year, according to a recent report. RBC, recently targeted by pipeline opponents as a major funder in Coastal GasLink, ranked fifth out of the world’s 60 largest banks with $48.4 billion in fossil fuel financing provided in 2021.

Industry has also benefited in smaller ways during the pandemic. By spring 2021, B.C. was directing rapid tests to industrial work camps under the Provincial Health Services Authority program, despite it taking another year for them to become widely available, even in high-risk settings like long-term care and public schools.

TC Energy didn’t respond to questions about what, if any, COVID-19 relief it received from government.

But throughout the pandemic, the company continued to raise quarterly dividends, maintaining its long-term average seven per cent growth rate, even as it projected cost overruns into the billions. Its CEO, Russell Girling, ranked 16th among Canada’s highest-paid executives in 2020, with overall income totalling almost $15 million.

For a moment, says Van Wager, it appeared that the pandemic might provide an opportunity for sober second thought about how our economy can adapt for climate change.

But that didn’t happen, she adds.

“I think a lot of people were hoping that the pandemic was a time where we could actually reassess and think about what things, what projects we think are critical, think about how we structure our economy,” Van Wager says, pointing to Ontario’s Bill 197, a July 2020 omnibus bill that made substantial changes to environmental laws while favouring extractive industries, all at a time when remote First Nations remained under strict lockdown.

“I think it’s really important to shine a light on the use of emergencies as cover for other kinds of political agendas around resource extraction and economic development,” she says. “There were a number of moves made by different governments across Canada, either project-specific or more broadly, while both the public and Indigenous communities have been distracted by emergency circumstances.”

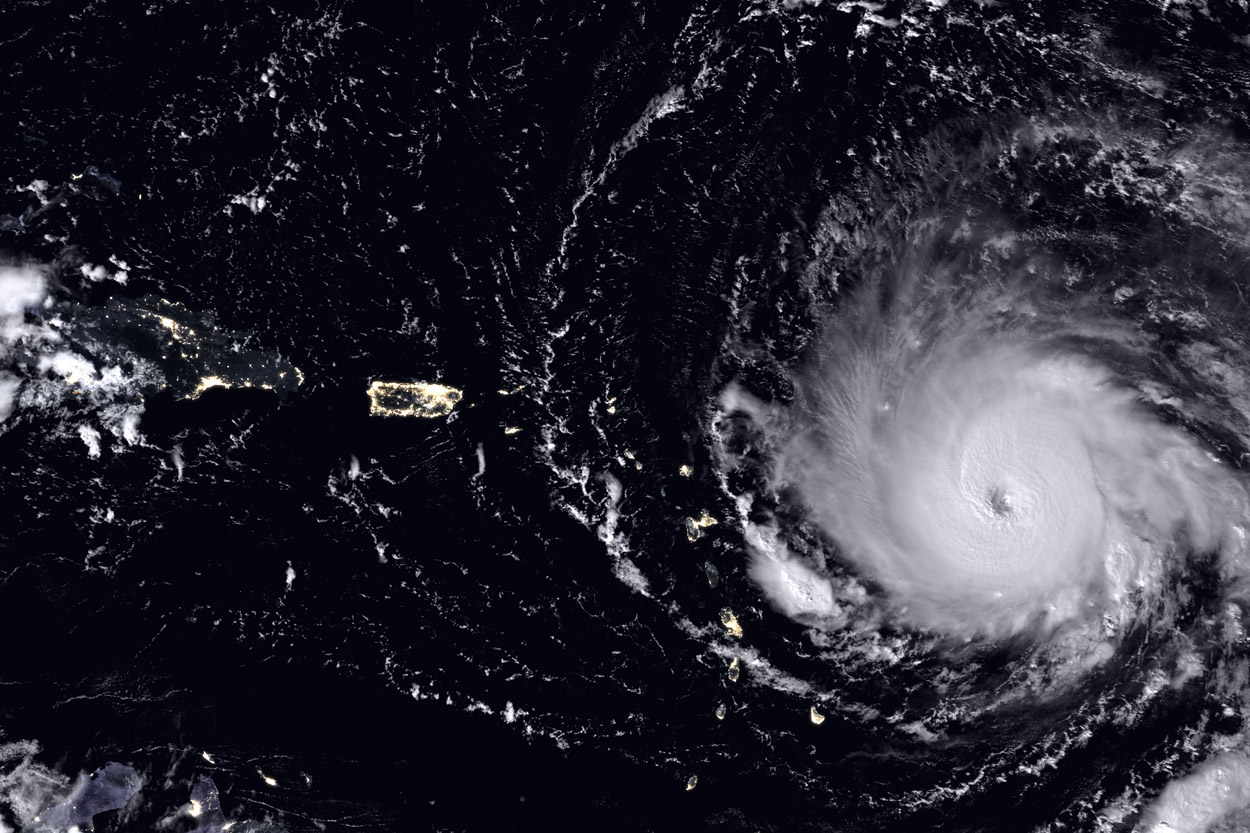

Expect more disaster land grabs in coming years, says Klein. She predicts opportunities to prioritize industry during times of extreme destabilization will become increasingly common, because, as she says, society faces “overlapping and intersecting emergencies” caused by climate change. Scientists have linked not just winter’s flooding but recent summers’ catastrophic wildfires and last June’s deadly heat dome to rising levels of carbon in our atmosphere.

Emergencies produce chaos and anxiety that strengthen the hand of the state. The pandemic may not have hit with the physical force of a hurricane, but the risks it posed to personal safety meant norms were suspended. People found themselves isolated. There was uncertainty and fear. According to Eli Lazarus, a geomorphology associate professor at University of Southampton, in tourism-dependent places like the Caribbean, the pandemic’s economic toll exceeds that of a natural disaster.

Szoke-Burke draws parallels between the Ebola epidemic in Liberia, when communities were unable to gather and government quietly signed agreements with industry, and what happened around the world during the COVID-19 pandemic. Doubts about the nature of the disease, how it was spread and whether vaccines were safe and effective made if feel unsafe for rural communities to come together, preventing them from deliberating collectively.

“It’s not that things were perfect prior to the disease outbreak and then they got bad,” he says. “It was a matter of things being very imperfect and then opportunistic, powerful actors exploiting a change in circumstances for their own gains.”

Disaster Land Grab in Liberia

At the height of the Ebola outbreak in Liberia in 2014, while the country was in a state of emergency, one palm oil company, Golden Veroleum Liberia, or GVL, was expanding its business.

“GVL [has] put our communities and people at risk,” said James Otto, from the Sustainable Development Institute in Liberia. “When state institutions were paralyzed, when civil society were incapacitated… the company used that as a means to kind of get things done.”

The company holds land use rights to more than 220,000 hectares of forest land in southeastern Liberia. The rights were granted by the Liberian government during a raft of investment concessions.

At the heart of this land dispute is the global demand for palm oil, which is thought to be in 50 per cent of supermarket products, from food to face wash.

“I have yet to hear of a case where an oil palm plantation hasn’t been somehow implicated in some sort of land dispute, in some sort of land conflict, where there haven’t been any human rights violations,” said Jasmin Hristov, an assistant professor in sociology and anthropology at the University of Guelph.

Between 2012 and 2018 several complaints were filed alleging that GVL coerced and intimidated community members, disregarded Ebola health protocols, failed to fulfil principles of free, prior and informed consent when signing agreements and didn’t deliver on stated community benefits.

In an interview, Michael Abedi-Lartey, general manager for sustainability at GVL, denied the allegations. He said GVL did not disregard health protocols, did not threaten or coerce community members and is working to fulfil commitments.

But James Otto says Ebola was just the first opportunity. “Disasters actually fuel land grabs. The companies use it. GVL used it,” said Otto. “They [used] Ebola to take the land away, and then they use COVID to drive people off their jobs and to shove them back into poverty.”

“So disaster has played a serious part. And it's much more serious in the case of Liberia because our governance system has been very weak.”

Here are the key events.

Timeline

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf takes office as the newly elected president of Liberia. Johnson Sirleaf is tasked with helping the West African country to stabilize and recover after 14 years of civil war that ended in 2003. The death toll from the war is estimated at 150,000 to 250,000 people. Hundreds of thousands were internally displaced and the country’s infrastructure was devastated in the fighting.

Johnson Sirleaf vows to rebuild the country with the help of foreign investment. During the postwar boom the Liberian government signs concessions for extractive industries like palm oil, rubber, forestry and iron ore.

GVL and the Liberian government sign a concession agreement granting the palm oil company the lease rights to roughly 220,000 hectares.

A community complaint is filed against GVL to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. The RSPO is an industry watchdog that monitors members like GVL for social and environmental responsibility. The complaint accuses GVL of disregarding land rights, desecrating religious sites and polluting water sources.

GVL signs four agreements with local communities.

The first case of Ebola is reported in Liberia.

When the world shut down in March 2020, the Coastal GasLink pipeline was already under construction through northern B.C., armed with all necessary permits from the province and a court-issued injunction. The law, proponents argued, was clearly onside with the pipeline and “rule of law” became the mantra by which to cheer the project forward.

But Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs maintain that they never consented to the pipeline, and so the project bypassed the free, prior and informed consent promised by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which B.C. made law in October 2019. Canada followed in 2021.

Merle Alexander is a Hereditary Chief of Kitasoo Xai x’ais First Nation who practises Indigenous resource law. He was part of the team that developed the B.C. legislation and continues to work on its implementation to bring the province’s laws in line with the U.N. declaration.

“It was known all the way through the entire process that the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs were against the project and the province and the companies consciously chose to just rely on Elected Chiefs and council to make decisions,” Merle Alexander says. “There isn’t any real legal guidance on what to do about whether you need to negotiate with Hereditary Chiefs or Elected Chiefs.” Such vagueness might have prompted a tapping of the brakes on proceeding with the pipeline until lines of authority were sorted out and enshrined in new formal agreements. Instead, the confusion was used by those backing industrialization of Wet’suwet’en territory to claim Indigenous support for pushing on with the project.

UNDRIP promises Indigenous self-governance. But it stops short of defining what that should look like, instead leaving the details up to each nation. And while Delgamuukw recognized the authority of the Hereditary Chiefs, there has never been a legal test of the groundbreaking case in court, Alexander says, calling the decision to approve the pipeline despite the fact that title claims are not yet resolved a “conscious gamble.”

In her decision granting Coastal GasLink’s injunction against Wet’suwet’en blocking access to the pipeline route, Justice Marguerite Church sidestepped the 1997 decision, saying simply that “the Aboriginal title claims of the Wet’suwet’en remain outstanding and have not been resolved either by litigation or negotiation, despite the urging of the Supreme Court of Canada.”

The injunction has provided a tool to remove opponents and push the pipeline through.

But, as Szoke-Burke points out, government’s tendency to prioritize industry during times of upheaval can backfire, leading to a greater risk of protests, social conflict and uncertainty for industry. “You can quickly see how the cracks are going to form and how it’s going to cause more problems than it solves,” he says.

Indeed, forging ahead with Coastal GasLink has done little to quell dissent.

During an April court appearance for those arrested in November, Justice Church noted that protests have escalated since she issued the injunction, saying, “The conduct alleged is defiant of the rule of law, and such conduct depreciates the authority of the court.”

In addition to the pandemic, climate change has layered on other disasters, atmospheric rivers that paralyzed parts of British Columbia last fall and a war that rocked global supply chains. The expansion of oil and gas infrastructure in contested territory proceeded, championed by governments, with Alberta Premier Jason Kenney recently tweeting, “Now if Canada really wants to help defang Putin, then let’s get some pipelines built!”

In November, even as the province experienced catastrophic flooding in the south, the B.C. government worked to provide policing resources for the two-day RCMP action against land defenders who blocked access roads, worksites and two work camps near the pipeline route.

Then, on Feb. 17 of this year, Coastal GasLink reported that masked assailants had descended on its drill site during the night, swinging axes, threatening workers and causing millions in damage to company equipment.

Unlike previous pipeline opposition, no one has ever claimed responsibility for the attack and, months later, police have made no arrests. But that hasn’t stopped RCMP from using the incident to increase patrols and disrupt life at Gidimt’en Camp — against the requests from Hereditary Chiefs to remove police forces from the territory.

Na’Moks likens the impacts to camp occupants’ ability to sleep or function in the midst of the patrols to interrogation and torture tactics — those reminiscent of the shock therapy methods referenced in Klein’s The Shock Doctrine.

For the first time, police officers began entering the camp in February, multiple times a day and throughout the night, asserting their authority on “Crown land” and saying they had found a link between the camp and the alleged Feb. 17 attack. The patrols continued, several times a day and into the night, at the time of publication.

RCMP did not respond to questions about what links exist between the camp and the incident, nor did they provide an update on their investigation. Instead, a spokesperson says the force increased patrols out of concern for safety of those in the area “after the violent confrontation against employees of Coastal GasLink.”

“While we have maintained a presence in the Morice Forest Service Road corridor since 2019, the RCMP has increased our presence patrolling around the industry camps and other camps along the route, and interacting with people in the area,” it said in an email.

Sleydo’ believes the February incident is being leveraged as another tool to remove them from the land.

“They’re purposely trying to get us off of the territory. They don’t want us to be there, and they’re trying to make life so miserable that we won’t be there anymore,” she says. “It’s obviously meant to wear people down.”

In the face of land grabs rooted deeply in colonial history, there is a growing chorus advocating for a reversal. The Land Back movement is a deliberate attempt to reassert Indigenous jurisdiction over their territories, by calling for the return of decision-making power to First Nations and the need for consent when it comes to resource extraction projects.

“The Land Back movement is colliding with the continuing history of land grabs,” says Alexander, explaining a goal is to integrate traditional Indigenous laws and governance with colonial ones. “I think that in the long term we will be successful because Indigenous peoples are just relentless advocates for themselves.”

Pasternak describes Land Back, alongside Black Lives Matter, as “two of the most powerful and effective social movements” underway.

“The amount of active land defence movements, and even more less-known assertions of jurisdiction over Indigenous lands, really betrays the claim by Canada that there was some kind of chronological, perfect unfolding of state sovereignty over an entire containerized territory of the Canadian nation state,” she says. “The Land Back movement shows that that was nothing but a bunch of tattered strings.”

Today Wet’suwet’en title negotiations have stalled, according to Na’Moks. The police presence on the territory has increased. And pipeline construction continues, despite the company’s repeated environmental infractions for damaging watersheds.

The company says it has overcome challenges during the pandemic to complete more than 60 per cent of the project, which remains underway.

But the Wet’suwet’en, who have occupied these lands since time immemorial, aren’t going anywhere, Sleydo’ says.

Instead, they are digging in.

This month, Gidimt’en Clan announced that it is building a new bahlats, or feast hall, where an ancient Wet’suwet’en village once stood at the confluence of Wedzin Kwa and Tsel Kiy Kwa, a short distance from Gidimt’en Camp. It is the location where Wet’suwet’en ancestors once harvested the now-scarce lamprey eel alongside other foods and medicines.

“There are permanent homes and Cas Yikh (Grizzly House) members are living full time as their ancestors have since time immemorial,” it says in a recent statement. “This will be available to all Gidimt’en Clan members and other clans of the Wet’suwet’en Nation to hold feasts for all things related to our governance system and lands.”

RCMP officers are a regular presence at the construction site, pulling in several times a day to observe activities before leaving again, just as they do at nearby Gidimt’en Camp, where the smell of cottonwoods mingles with woodsmoke and life continues despite the interruptions. Meals are served, people gather around a bonfire and children play.

For Na’Moks, being on the land brings a sense of peace.

“When industry comes in, and then governments fall in place, and you know that you’re collateral damage, that doesn’t mean you have to go quiet,” he says. “You can remain peaceful. But that doesn’t mean you have to go quietly.

“I can’t speak for all Indigenous people, but for Wet’suwet’en. We don’t want more than what we have. We just want to keep what we have.”

Additional project credits

EditingBritney Dennison, Andie Crossan, David Beers

Reporting and researchKatarina Sabados

Design and developmentAndrew Munroe

Additional credits for timelines and visualizations

Reporting and researchEmma Gillies, Mashal Butt

Contributing editorDavid McKie

Field reportingHarry Browne (Liberia), Varney Kamara (Liberia), Bong Sarmiento (The Philippines)

Fact-checkingSharon Nadeem, Mashal Butt, Sonal Gupta, Rithika Shenoy

This project was produced in partnership with fellows of the Global Reporting Program. See the full project team.

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: