Jennifer Thompson lives on a shaded street in New Westminster, B.C., a city of 71,000 located on the banks of the Fraser River, around a 30-minute drive east of Vancouver. Her neighbourhood is filled with colourful Victorian-era houses. Picket fences guard neatly-kept lawns, ornamental shrubs and fruit trees.

On Monday, June 28, Thompson noticed something unusual. There was a car parked in front of her house in the shade of a cherry tree, and it was making a strained revving sound. Glancing inside, Thompson could see a woman in her late 60s or early 70s, leaning back in the reclined seat. Thompson asked the woman if she needed help.

“I'm really grateful that she said, ‘I'm not OK,’” Thompson said.

Depending on where you live in Metro Vancouver, temperatures that day had soared to the low to high 30s, but in many communities it felt like 40 to 46 C. Many residents hadn’t fully grasped that B.C., along with Washington and Oregon, was locked under an unusual weather system called a heat dome trapping the high temperatures. It wasn’t cooling off overnight, and the heat had been building for days.

With the help of her husband, Kurt, Thompson helped the woman out of her car and into their house. They led her down the stairs to the basement, where family members had been sleeping to get a break from the heat.

The woman told her new hosts that her name was Carol*, but she was disoriented and weak. The couple gave her water and food and applied cold towels to the back of her neck to try to cool her down, but it didn’t seem to be helping much.

They asked if they could help take her home, but Carol said no: she was sure if she went back to her apartment, she would die. Later, Thompson would learn that Carol had been sleeping in her car for two nights with the air conditioning on to try to get some relief from the heat.

When Thompson called 911 for an ambulance, the dispatcher told her it would take between eight and 12 hours for paramedics to arrive. Thompson urged Carol to let the couple take her to the hospital, but she refused to go. So they decided to let Carol stay overnight in their basement.

“We were worried that she would die in the basement,” Thompson said.

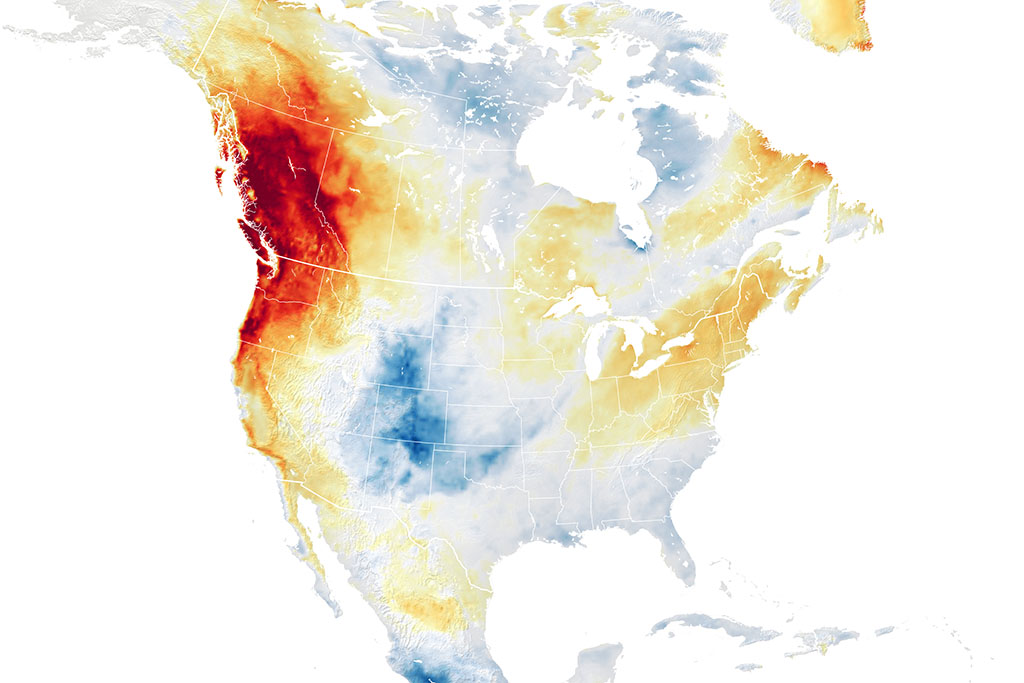

The conditions that led to Canada’s deadliest weather event started 8,500 kilometres away in China. Heavy rains there that started in June injected moisture and energy into the jet stream — bands of air that travel across the globe.

“The jet stream with all that energy went into a very high-energy state, where it started behaving kind of like a wave does,” said Jeff Masters, a meteorologist at Yale Climate Connections.

Masters described the way the jet stream behaved as “extreme,” thrown out of whack by all the extra moisture from the unusually heavy rains that caused catastrophic flooding in China.

“Normally in the jet stream, these ripples that form just kind of propagate along and don't stay in one place for any long period of time,” Masters said.

Like a kinked vacuum cleaner hose, the jet stream that travels across the Pacific Ocean became contorted. Then, it froze in place for days.

“You got a very sharp bulge to the north over western North America,” Masters said. Under the bulge, a ridge of high pressure was keeping unusually warm air that had flowed up from the tropics and subtropics locked in place.

Under this dome of air, the heat started building up. Over the course of the five-day event, temperature records were smashed across B.C., Washington and Oregon. On Tuesday, June 29 the town of Lytton, B.C. notched the highest temperature ever recorded in Canada, at 49.6 C. The next day, a wildfire levelled the town.

Temperatures began to drop on July 1. But by then, over 800 people had died in B.C., Washington and Oregon. B.C. counted the highest number of deaths: 595 people died of heat-related causes during the summer of 2021, according to the BC Coroners Service. The number makes the June 2021 heat dome the deadliest weather event in Canadian history, in a country that regularly endures bitterly cold winters, violent storms and wildfires.

In comparison, 100 people died in Washington and 110 people died in Oregon. Compared to B.C., Washington has 2.5 million more people, and Oregon has 853,000 fewer.

Unlike more dramatic weather events like tornados, hurricanes and floods, there was no dramatic footage to illustrate the horror of the event. The victims of the heat dome died at home, out of the public eye. They were found by family members, neighbours, paramedics and police officers, sometimes in front of a fan with a glass of water at hand. Some had tried to call for help, and died waiting for an ambulance. Some never knew how much danger they were in.

Others survived, but sustained serious injuries to their brains, kidneys or hearts that required lengthy hospitalizations. And some people died weeks after they were admitted to hospital.

There is no doubt that the heat dome was caused by human-caused climate change, said Nathan Gillett, a meteorologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada. With other scientists, Gillett contributed to a study that found that the event would “have been virtually impossible” without climate change.

“The study looked at climate model simulations to see how much human-induced climate change had increased the risk of this event, and it concluded that the risk had increased by a factor of at least 150,” said Gillett.

Under current climate conditions, the study estimates that the heat dome event will happen once every 1,000 years. Right now, the climate has warmed by 1 C above pre-industrial conditions. If the climate warms by 2 C above pre-industrial levels — the track we’re currently on if countries don’t further reduce greenhouse gas emissions — a heat dome event similar to the one that hit British Columbia, Washington and Oregon could happen every 5 to 10 years.

“These kind of analyses tell us: Has climate change affected the risk of this kind of event? Is it going to become more frequent in the future? That does help,” Gillett said. “It helps people respond to it in developing building codes or protocols for heat waves.”

The province says it’s now working on a plan for next summer, but so far has released few details.

The Tyee spoke to first responders, doctors, public health officials and municipalities to try to determine what went so wrong during the most extreme heat wave the region has ever experienced, and what could be done next time to save lives. We also examined practices in Oregon, where the response in some cases was faster and more assertive as the threat mounted.

June 22 to 24, 2021: ‘Every day the forecast got a little worse’

In Portland, Oregon, Chris Voss was watching the forecast grow increasingly worse. What had at first looked like an ordinary heat wave was looking more and more unusual.

Initially, Voss recalled, the forecast showed a 50 per cent chance that temperatures would rise above 100 F, or 37.7 C, on one day of the upcoming heat wave.

“Then it became: OK, now there's a 50 per cent chance that all three days will be over 100 degrees,” said Voss, who is the director of emergency management for Multnomah County. “So every day the forecast got a little worse.”

The county was already planning to open cooling centres, air-conditioned spaces like libraries and community centres where people can get a break from the heat. But on June 22, four days before the heat wave was expected to hit, Voss and his team made the decision to keep cooling centres open for 24 hours, including the Oregon Convention Center, a facility that could house hundreds of people in an emergency. It was the first time the county had decided to run the facilities throughout the night.

“Normally, we would open cooling centers for the hottest part of the day,” Voss said. “But through consultation with the health department and the National Weather Service and others, and hearing what the nighttime lows are going to be, the decision was made to keep them open 24/7 until the heat dome had sort of broke.”

In New Westminster, similar conversations were taking place. The city had never opened cooling centres in the past, but there had been a growing realization that they were going to be needed, said Jonathan Coté, the mayor of New Westminster.

In Burnaby, a city of 250,000 that sits between Vancouver and New Westminster, city staff were also trying to figure out how to open cooling centres in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. One idea was to use city-owned parkades: they weren’t air conditioned, but they would provide some shelter from the heat, while avoiding crowding people together indoors where they might run the risk of transmitting the virus.

On June 23, New Westminster Fire and Rescue Services staff held an emergency meeting to plan for the upcoming heat wave.

“When some of the predictions were coming through… then we sat down as a group and said, you know, this is impending,” said Kevin Urton, an emergency management program officer with New Westminster’s fire department. “This looks critical and life threatening.”

Urton said there were information gaps between municipalities and the provincial agency Emergency Management BC.

“Normally we get (weather) bulletins from Emergency Management BC,” Urton said. “They'll send information out to emergency managers, they have a distribution list that covers the southwest region of the province.”

But as the heat wave approached, “there were no notifications from them, so we looked at what Environment Canada was projecting for the city.”

According to a report from City of Burnaby staff, the city got a warning about the upcoming heat wave from Environment Canada around noon on June 22, but didn’t receive any communication from Emergency Management BC until June 25.

A review of Twitter posts shows that Multnomah County began warning about the upcoming heat wave on Wednesday, June 23, using language that emphasized that the heat would be record-breaking. The messages on that day included information about cooling centres that would be open starting June 25.

The City of Vancouver posted a warning about the heat wave on June 23, with a link to an Environment Canada advisory. On June 24, the city posted another warning with tips on how to keep cool and a link to information about cooling centres. Burnaby and New Westminster first posted about the extreme heat on June 25.

On June 24, Fraser Health — the health authority that includes Burnaby and New Westminster — urged residents to check on family and friends who could be vulnerable to heat by phone or video call. Vancouver Coastal Health didn’t issue any warnings until June 25.

June 25 to 27: ‘I witnessed everything sort of crumble’

On Friday, June 25, Kevin Marriott was heading into two day shifts followed by two night shifts as a dispatch supervisor with the BC Ambulance Service. Marriott has been an ambulance dispatcher for 20 years, and before that worked as a paramedic for a decade.

Heading into the weekend, Marriott said he noticed it was busy during his day shifts on June 25 and 26, but the Vancouver dispatch centre wasn’t receiving an unusually high number of calls. It was a typical summer weekend, with people heading out to enjoy the weather and getting into the usual number of accidents and scrapes. The province had just relaxed several COVID-19 restrictions, and people in B.C. were keen to start travelling and getting together with family and friends.

That pace shifted when Marriott headed into work on the afternoon of Sunday, June 27, the first of two back-to-back night shifts. The call volume had been building throughout the day, and going into the evening the calls started to shift, from the usual range of incidents to calls from people who were suffering from the heat.

Shelby Weber noticed the same thing. Weber works as a paramedic in Surrey, a sprawling city of 500,000 a 45-minute drive east of Vancouver. She’d picked up a 6 p.m.-to-midnight shift on June 27, and as her shift came to an end, she and her partner could hear calls coming in over the radio.

“You could sort of feel that ominous writing on the wall. The temperatures weren't predicted to get any cooler, and you could already hear the cardiac arrests that were coming in multiples over the air,” Weber said.

When Marriott started his shift at 5 p.m. on June 27, there was already a backlog of calls. During the next 12 hours, the dispatchers on duty never caught up. People were waiting up to 25 minutes just to talk to a dispatcher, and then they were waiting hours for the ambulance to arrive.

As the hours ticked by, the stress started to build among the dispatchers. Marriott saw some of his staff weeping at their desks. They couldn’t keep up with the calls.

“It was a lot. I witnessed everything sort of crumble,” Marriott said. “And then you trying to hold all that together and keep yourself composed.”

The clock finally read 5 a.m., and Marriott’s shift was over. He felt exhausted and numb; it was the worst shift he’d ever worked. But it wasn’t over.

June 28: ‘The system was not working’

Marriott went home to his air-conditioned house in East Vancouver and tried to sleep, but he kept waking up. Finally he got up and went to work two hours early to try to prepare for the next night shift. Marriott talked with the day-shift supervisor, trying to get a sense of where in the region it was the busiest.

“We talked about spots that are super busy — there's always kind of a theme, certain areas will be sort of the hot spot where it's just busy all day for some reason,” Marriott said.

But between June 27 and 29, “it was literally everywhere. It didn't matter if it was downtown Vancouver or Bowen Island. It was busy everywhere.”

At 10 p.m. that evening, Dave Meers was at home in bed when he got a call from the firehall. When the assistant fire chief arrived at Firehall No. 1 in Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood, he found Chief Karen Fry and two deputy chiefs monitoring a huge volume of calls.

“They looked at me at and said, all of the firehall apparatus, every single apparatus, is committed right now,” Meers said, using the term for a fire department vehicle staffed with a crew.

“They’re all at a medical incident. I’m pretty sure that was unprecedented — I don't remember ever hearing that in all my years as a firefighter.”

Meers and the other chiefs got on the phone, calling every off-duty firefighter in to work.

What made the heat dome so dangerous was not just how hot it was getting during the day, but the nighttime temperatures. Normally, people who are suffering from heatstroke or other effects of a hot summer day can recover at night as the temperature drops.

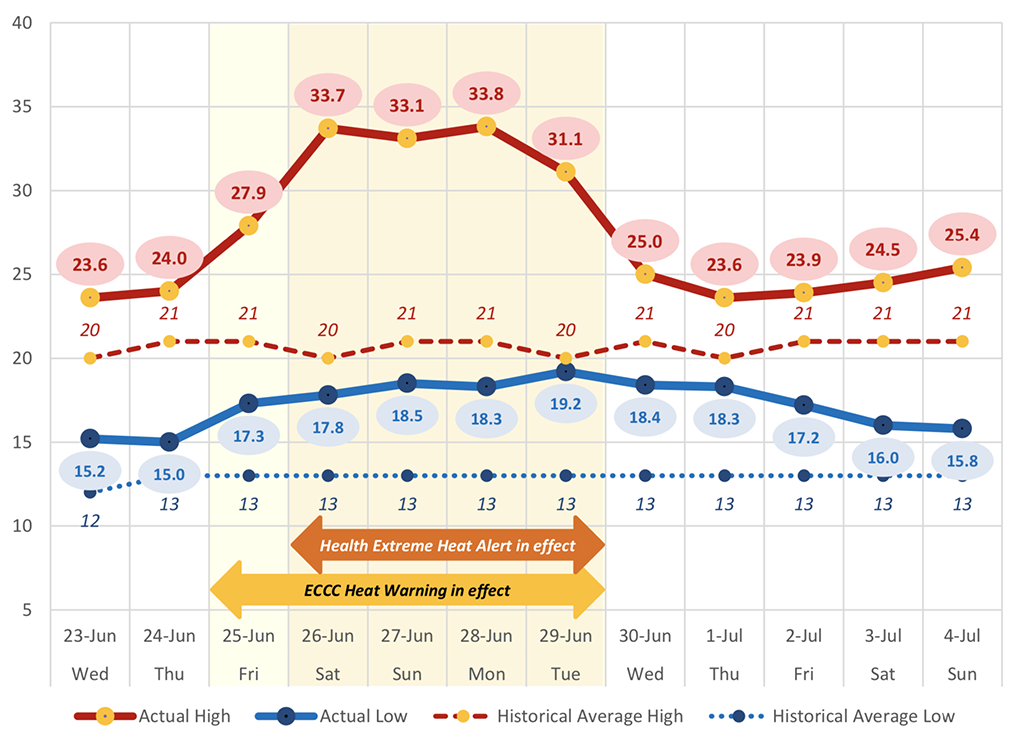

But during the heat dome, not only was it getting unusually hot during the day, it wasn’t cooling off at night. June 28 was the hottest day and the hottest night of the heat dome. In Vancouver, the high that day was 33 C, but it felt like 38. Overnight, temperatures fell to 17.5 C; a normal nighttime low for that time of year would be more like 13 C.

Inland, temperatures were much higher: in Surrey on June 28, the temperature rose to 37.5 C, but with humidity, it felt like 46 C. At midnight on June 28, it was still 22.8 C. In Abbotsford, an hour east of Vancouver, temperatures rose to a high of 42 C, but it felt like 50 C with humidity. At midnight, it was still 27.8 C.

Extreme heat can cause a range of serious injuries. When people get severely dehydrated, there’s not enough fluid and blood in their bodies to get enough blood flow to the kidneys. The kidneys are organs that filter waste, toxic substances and excess fluid from the body and expel the waste in urine.

“When you are dehydrated and don't have enough fluids, enough flow to the kidneys, your kidneys start to shut down,” said Dr. Elise Jackson, an internal medicine resident who worked at two Vancouver hospitals during the heat dome. “As a result of that, you get a lot of other complications.”

Toxins can start building up inside the body, and patients’ potassium and sodium levels can also rise to dangerous levels. A guide produced by the U.K.’s National Health Service explains the role potassium and sodium play in keeping the body functioning properly:

“All the cells in the body, apart from those of the outer skin, are surrounded by a fluid called the extracellular fluid. For the cells of the body to work properly, the extracellular fluid needs to have a stable composition of salts — such as potassium and sodium — and acidity (often referred to as pH). The kidneys are central to maintaining these correct balances and the effective functioning of all the cells of the body.”

But if the kidneys aren’t working properly and there is too much potassium and sodium in patients’ bodies, “that can then cause quite severe symptoms,” Jackson explained.

“You can get a lot of cardiac events and cardiac arrests, as well as confusion, headaches, malaise — just feeling really unwell.”

Getting overheated can also cause brain injuries.

“When you have a fever, or when you get overheated, your brain uses up a lot more energy and a lot more oxygen,” Jackson said.

“You can actually get quite severe, long-term brain injuries — because the brain just can't handle being that hot for a long time.”

In the ambulance dispatch centre, the situation was getting worse.

“There were a ton of cardiac arrest calls, but those didn't necessarily start out as cardiac arrest,” Marriott said.

“Somebody might be feeling dizzy. It’s hot, they’re dizzy, they have a headache and are feeling sick. And then, let's say two hours later, they're starting to feel worse.”

Marriott said many calls would start out as a “routine response,” meaning no lights or siren, but as dispatchers stayed on the line, the call would escalate all the way up to “a code 3 response.”

In Vancouver, it was taking hours for ambulances to arrive. Often, firefighters — who have advanced first aid training — were arriving first, but were unable to follow the usual procedure of handing the patient off to paramedics. That meant firefighters were getting stuck for hours at calls. The longest medical incident started just before midnight on June 28, and firefighters stayed with the patient for nearly 13 hours.

“Their condition was such that we couldn't just leave them, and we couldn't get relieved by an ambulance,” Meers said.

The situation was the same in New Westminster. The fire department doesn’t ever transport patients to hospital, but during the crisis staff made the difficult decision to change that protocol. Fire trucks aren’t designed to carry people to hospital, so instead patients were put into taxis or driven by family members while fire crews followed behind.

“I just remember that being one of the stressful decisions — we didn't even know what the consequences of breaking the protocol necessarily would be,” said Jonathan Coté, the mayor of New Westminster.

“But the system was not working. We had to find a way to get people to the hospital, but we also needed to find a way to get the fire crews to be able to get their next call because the backlog was just growing.”

People were dying before help could arrive. If someone is discovered dead in their home, the police and the coroner both attend. But with so many deaths, it was taking a long time for coroners to arrive, leaving police unable to leave for hours. The whole system had ground to a halt, leaving patients to die in sweltering apartments and first responders with serious psychological injuries.

“I actually have sought help with a psychologist from our critical incident stress program, because it took such a toll on me,” said Marriott.

June 29: ‘The fellow around the corner from us did die’

For paramedics and health-care workers in Vancouver, the ordeal was far from over.

Weber, the paramedic in Surrey, started work that day at 6 a.m. On a usual shift, paramedics respond to one cardiac arrest or less. But over the course of her 12-hour shift, Weber responded to a total of eight heart attacks.

While Weber and her partner moved some patients to the air-conditioned ambulance to cool them down, cardiac arrest patients can’t be moved.

It was exhausting, and Weber and her partner had to make sure they weren’t becoming dehydrated or heat exhausted themselves.

“Paramedics described going into basement suites where it was upwards of 50 C,” said Troy Clifford, the president of the union that represents paramedics in B.C.

At one point, Weber could hear instructions from the dispatcher to another ambulance crew over the radio. To her horror, the dispatcher was telling that crew to cancel a previous cardiac arrest for “a more viable sounding cardiac arrest.”

“So not only do we not have enough cars to go to every single call, but we don't even have enough cars for the high acuity calls that we have going on in the area,” Weber said.

“We're constantly being diverted to the most high-acuity calls, but I’d never heard that before, to (cancel) one high-acuity call for literally the same thing.”

Many of the calls Weber and her partner responded to were inside older apartment buildings with no air conditioning. That was a common theme throughout the Metro Vancouver area: low-income people living in older, more affordable apartment buildings were hit hardest by the extreme temperatures.

In New Westminster, Jennifer Thompson’s houseguest, Carol, was feeling a better after spending the night in the Thompson’s cool basement. Thompson’s husband went out to buy a fan, ice and food and went to Carol’s apartment to make sure it was cool enough for her to return. Later that day, Carol was able to go back to her home, Thompson said.

Like many of the people Weber had been treating in Surrey, Carol lived in an older three-storey apartment building with no air conditioning, just eight blocks away from Thompson’s tree-lined neighbourhood of single-family homes. Census data shows median income in Carol’s downtown New Westminster neighbourhood is between $32,000 and $47,000, compared to $116,000 to $141,000 in Jennifer’s Queen’s Park neighbourhood.

When New Westminster Fire and Rescue analyzed data from the heat dome period, staff found that many of the calls for help were clustered in the Brow of the Hill neighbourhood, an area of the city where many low-income seniors live in older, more affordable apartment buildings.

Burnaby staff have noticed the same pattern: many of the calls for help came from neighbourhoods like Metrotown, where older apartment buildings are common.

An analysis by researchers with the BC Centre for Disease Control found the highest death toll from the heat dome happened in New Westminster and in Vancouver’s poorest neighbourhood, the Downtown Eastside.

The BCCDC’s analysis showed that people who were low-income, elderly and socially isolated were at the highest risk of dying, but even just one of those factors increased the risk of death during the heat wave.

“The fellow around the corner from us, two houses away, did die,” Jennifer said. The 80-year-man lived alone, she said. “He had nobody there, and didn’t realize he was overheating.”

June 30 to July 2: ‘All of us were seeing medical presentations we haven't seen much of before’

By June 30 it felt like a very hot summer day instead of like being trapped inside an oven. For paramedics, the call volume was easing, but it was still worse than normal. In half of the cardiac arrest calls Weber attended that day, the patient was already dead by the time she and her partner arrived.

In Metro Vancouver, hospitals were also filling up with patients suffering from kidney and brain injuries. On July 1 and 2, Jackson was working at Vancouver General Hospital. On July 2, there were 166 patients admitted to the internal medicine department, the highest number ever recorded; a normal volume is around 100. Patients were being treated in the emergency room for days, or placed on other wards.

Some of the patients simply needed fluids and rest, but others had such serious kidney injuries that they needed dialysis.

“All of us were seeing medical presentations we haven't seen much of before. Certainly you see kidney injuries and sodium abnormalities and stuff, but not because of heat,” Jackson said.

“And I think the prevalence of these brain injuries that happen because of the heat was also quite shocking to a lot of people.”

Many of the patients who suffered heat-related injuries were elderly, had cognitive or mobility disabilities, or lived in inadequate housing, Jackson said. People with cognitive disabilities may not recognize they need to drink more water or do other things to try to cool down, while people with mobility issues “just physically weren't able to do the things that they needed to do to keep themselves safe, like take cold showers, drink enough water,” Jackson said.

While many patients recovered, some died weeks after being admitted to hospital.

Data released by the BC Coroners Service shows that while 526 people died during the heat dome event, another 67 died between July 2 and Aug. 12.

“The injury [that took their life] was actually the heat injury that occurred initially in that week, but the people sadly ultimately succumbed in the weeks after,” Dr. Taj Baidwan, chief medical officer for the BC Coroners Service, told CTV News. “The organs take time sometimes, and the body fights against dying. Essentially those processes take time, and that's what we saw."

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, the many failures of the ambulance service were under intense scrutiny. Documents obtained by the BC Liberal Opposition through freedom of information requests showed that in the weeks leading up to the heat dome, senior leadership at E-Comm 911 had issued dire warnings about staffing problems at B.C. Ambulance Service.

During the heat dome, the B.C. Ambulance Service didn’t activate its emergency management centre until the most extreme temperatures had passed — a response that could have helped with staffing levels and co-ordination.

In response, Health Minister Adrian Dix announced the service would hire more paramedics. Two top executives in the B.C. Ambulance Service moved to different jobs in the provincial health system.

But Meers, the Vancouver firefighter, and Marriott, the ambulance dispatcher, say any system would have been swamped by the sheer number of calls on June 28 and 29.

“It was literally overwhelming,” Marriott said. “Even if we had all our staff and all the ambulances on the road that we're supposed to have, it still wouldn't have made a difference.”

Meanwhile, in Portland, Oregon, health officials say the first responder system was strained, but didn’t collapse as it did in Metro Vancouver. Voss, the director of emergency management for Multnomah County, said the 24-hour-cooling centre in Portland’s convention centre was well-used.

“I walked in there on day three during the day and there had to be over 500 people in the convention center — and 150 dogs,” Voss said.

Baidwan, the chief medical officer for the BC Coroners Service, told The Tyee that one of the reasons B.C. may have recorded such a high death toll compared to Oregon and Washington is that those states regularly get higher summer temperatures than B.C., so they may have been better prepared for the very high temperatures. Another factor, Baidwan said, may have been a letter he sent to doctors and nurse practitioners during the heat wave, reminding them that deaths due to heat-related causes should be recorded as accidental, not natural, deaths.

Dr. Sarah Henderson, one of the BCCDC researchers who analyzed factors that contributed to heat dome deaths, said cooling centres were available throughout B.C., but they weren’t used that much. She said creating a registry of vulnerable people, increasing green space in deprived neighbourhoods, and improving communication and outreach could help prevent a similar tragedy in the future.

When another heat wave hit the region in August, Vancouver, New Westminster and other cities did open cooling centres throughout the night, in contrast to the daytime-only services that were offered during the heat dome.

Urton, the emergency management program officer with New Westminster’s fire department, said the city’s response in the future could include having city staff going into apartment buildings in high-risk neighbourhoods to speak directly to residents to make sure they’re aware of the danger and know that options like cooling centres are available.

“We utilized all our traditional communication channels and went full out,” Urton said. “But I think we very quickly realized our traditional communication channels missed probably some of the most vulnerable people in this crisis.

Henderson also emphasized that people died inside their homes, where temperatures can rise higher and take longer to cool down than outdoor temperatures. Just 34 per cent of homes in British Columbia have air conditioning, compared to 80 per cent in Portland, Oregon. All of the people who died in Multnomah County either did not have air conditioning or central air, or their air conditioning units were not working properly, according to a report by public health officials.

Henderson said public health agencies in B.C. need to work with Environment Canada and other partners to establish thresholds for temperatures inside homes, and determine when to sound the alarm about temperatures that are getting dangerously high.

The province says staff at the Ministry of Health and the BCCDC are now working together to develop a new heat alert system. That system will have two alert levels, called heat warning and extreme heat emergency. The committee tasked with the work is also identifying public health actions that will happen when heat warnings and extreme heat emergency alerts are issued by Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Emergency Management BC and the Ministry of Health are developing a provincial extreme heat framework, identifying what different levels of government will do when extreme heat waves happen. The province is also working on preparing a new preparedness guide that “will focus on helping people manage in their homes or plan to relocate.”

The province says the work will be completed by the summer of 2022.

“I am a firm believer in the idea that we have to anticipate we’ll have another event like this next summer,” Henderson said during a presentation of her research in September. “Statistically it’s unlikely, but from a health perspective it’s the only sane way to move forward.”

* The Tyee was unable to contact the person Jennifer and Kurt Thompson helped, so we’ve used a pseudonym to protect her privacy. ![]()

Read more: Health, Housing, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: