Natalie Livermore, a health-care worker living in Pemberton, was shocked and angry when she heard that the town’s only bank would be shuttered in a few months’ time.

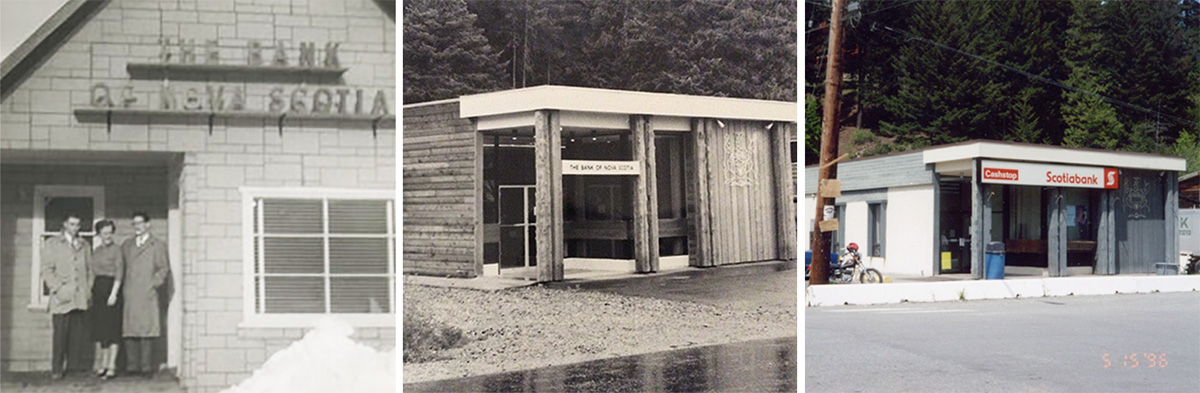

Pemberton’s Scotiabank branch has been a regular fixture in the booming town almost as long as it has legally existed.

But on Jan. 6, the bank announced — without any prior consultation — that it would close its one branch on July 15. Customers would then be referred to the Whistler Creekside branch, which is smaller and about 40 kilometres south.

That same day, Livermore started a petition urging Scotiabank to keep the branch, which currently has almost 2,400 signatures. About 3,100 people live in the town.

David MacKenzie, her neighbour and manager of the Pemberton Valley Lodge, also organized a letter campaign and a rally in front of the bank a week later.

A bigger puzzle fuels their frustration: Why is a rapidly developing community like Pemberton facing the loss of its financial hub?

“We never would have thought they would yank our bank out of our town,” said MacKenzie. “Pemberton is growing in leaps and bounds.”

In its communication with community members and The Tyee, Scotiabank has repeatedly declined to provide its reasons for pulling out, saying only that “the matter was not considered lightly and that complex factors were studied.”

But what is becoming clear to this community — like many rural, remote and Indigenous communities across Canada — is the cost of losing a brick-and-mortar bank branch.

Even as the COVID-19 pandemic speeds up the move to digital banking, poor internet connectivity threatens to leave these areas behind and force many to travel for hours to access basic services.

While alternative models like credit union and postal banking exist, many say there is still a way to go before they could fill the gaps left behind by the banks.

‘A town this size needs a bank’

In Canada, bank branch closure is not rare. But some closures have a bigger impact than others.

For rural, remote and Indigenous communities without multiple local banking options, a branch closure usually means increased travel time, sometimes on unsafe roads. Sean Markey, professor of planning at Simon Fraser University, called it a byproduct of decisions made without a rural lens.

“Often, these decisions might be made in a central urban core or even another part of the country without a real deep appreciation of the rural dynamics and challenges,” he said.

The Scotiabank branch in Pemberton also services residents of nearby remote and Indigenous communities like the Líl̓wat Nation, which is the third largest First Nation in B.C. with almost 1,500 people living in the community.

“We’re the service centre for the whole region,” said Meredith Kemp, executive director of the Pemberton & District Chamber. “So now imagine all those people who are travelling 15 minutes, 30 minutes to an hour to come here, and then now they have to drive to Whistler.”

Livermore says her drive to Whistler is about 30 minutes on a good day. During ski season or when it’s snowing, it could take her from 45 minutes to two hours. Meanwhile, public transit offers very limited options.

This closure is particularly jarring for a town with an expanding population. Pemberton has continued to grow rapidly since being recognized as B.C.’s fastest-growing community in 2005.

Kemp said there’s been a housing construction boom over the past few years, with more than 100 building permits issued in 2020 alone. The community is also seeing a growth in traffic.

Residents are now worried the branch’s impending closure could hurt their thriving local economy.

After more than a year of surviving COVID-19’s devastating economic impact, MacKenzie is angry that his business will soon incur new operation costs, mainly transportation, due to the bank closure.

He also worries that people who travel to Whistler will spend money there, hurting businesses that have counted on Pemberton’s role as a hub for shopping and services.

“I don’t think people will realize this trickle-down effect until the bank is gone,” he said.

Scotiabank said that it will leave a full-service bank machine in Pemberton but could not yet confirm its location this week. The bank said it will also invest $25,000 into the community over the next five years.

Many don’t think these concessions are enough.

“If we all move our business to another chartered bank in Whistler, maybe that bank would be interested in building a brand-new branch in Pemberton,” MacKenzie said.

“There’s enough going on here that one of them’s going to be interested. We’re growing, and a town this size needs a bank.”

Online banking ‘not a dependable service’

A persistent lag in internet connectivity for many rural, remote and Indigenous communities makes online banking even less accessible than distant bank branches.

While the vast majority of urban households in B.C. can access the official recommended 50/10 Mbps internet speeds, only 38 per cent of rural communities and rural Indigenous communities can.

Pemberton residents say their internet connectivity has only improved in recent years. And this gap persists for many nearby remote and Indigenous communities, even as the federal government works to improve the area’s internet connection.

Many also pointed out that there is a generational gap where most seniors simply prefer in-branch banking and banks still recognize it as “a valued method.”

“[The internet] is not a dependable service,” said Líl̓wat Nation’s political Chief Dean Nelson. “For some, it is. For some, it isn’t.”

Scotiabank said in a statement that it is giving Pemberton funds to procure 10 laptops at the local library to help residents access online banking.

Nelson similarly said Líl̓wat Nation is looking to provide laptops in central areas, but he acknowledges there will be challenges with the adjustment. His community is also considering starting its own branch with another chartered bank, but the idea is still in its early stages.

‘People before profit’

Are there financial institutions that have a community lens? SFU’s Markey thinks so. Credit unions tend to do a much better job of servicing rural communities, he said.

A credit union, BlueShore Financial, already exists in Pemberton, but many residents haven’t interacted with the system before, with some expressing worries about its accessibility and its capacity to support full banking services.

BlueShore Financial declined to comment for this article. But in a statement to the Pique Newsmagazine, branch manager Holly Hetherington said the credit union is working to ensure that people are aware that it can take care of the community’s needs.

Fraser Lake Mayor Sarrah Storey thinks community members should give credit unions a chance.

In 2019, the village in central B.C. lost its one CIBC branch, forcing many residents to drive 45 minutes to Vanderhoof or two hours to Prince George just to bank. The internet connectivity in the area is also “not great,” Storey said.

The village finally caught a break last year with the arrival of a credit union. Although it is only open two days a week, she said the credit union has been “really helpful” and committed to “building their roots” there.

“At the end of the day, I get it about shareholders,” Storey said, “but sometimes we have to think about people before profit.”

Credit unions are also a popular way of banking in the province. Forty per cent of British Columbians already bank with them and they serve as the only financial institution in 37 communities in B.C., according to the Canadian Credit Union Association.

Still, credit unions are unlikely to quickly and completely fill the gaps left behind by bank branch closures. While some are expanding their footprint, the association’s current priority is protecting existing credit unions — many being one-branch operations — and helping them comply with increasingly robust regulations.

“So right now, it’s not about opening new branches,” said Henry Han, the association’s regional director for B.C. “It’s about maintaining where we have [credit unions] that are the only financial institution and making sure that their costs are manageable.”

A new, old idea

Postal banking — where post offices would also offer banking services — has returned in recent years as a suggested alternative for underserved communities.

While many Pemberton residents told The Tyee they have not heard of the idea before or worry about the post office’s capacity to handle more responsibilities, postal banking is not a new idea.

Many countries like France and Japan already offer the service in various models and a postal saving system actually existed in Canada until around 1968.

These days, advocates like the Canadian Union of Postal Workers are hoping to expand postal banking through Canada Post beyond its current limited partnership with MoneyGram.

Canada Post already had close to 6,100 outlets as of 2019. Postal outlets also already exist in many communities that have neither a bank nor a credit union, like rural areas and First Nations reserves.

“It could be like a real bank,” said Lydia Tabard, the national co-ordinator of Delivery Community Power, a CUPW-affiliated campaign that was relaunched in January to champion postal banking and other goals.

“We would like to offer the exact same services as a regular bank, but with lower fees. There is no interest in making huge amounts on the back of people.”

The Canadian Bankers Association maintains that “there is no clear public policy objective or existing gap in the marketplace” for the government to enter banking through Canada Post.

But there has been an increasing openness to exploring postal banking in Canada, with many municipalities endorsing the idea. And since last year, Canada Post and the Canadian Postmasters and Assistants Association have been studying the idea through pilot projects.

“This is the best moment to push [our advocacy] as far as we can,” said Tabard, adding that an adequate system would need to go beyond putting bank machines in post outlets.

Still, it remains to be seen if this model could once again become the norm and how quickly it could roll out across Canada.

Ultimately, the “visceral” response of small communities to a branch closure could mean something much more personal, Markey said.

“Whenever there’s a business closure like that, people try to figure out what it means,” he said. “Is our autonomy in trouble? Is our community in trouble?”

Pemberton’s residents can’t say for sure what will happen yet, but they know the impending change would remove an essential service for the area — and a piece of their past.

“There’s a history here and they’ve been a pillar of our community,” said Kemp. “They’re our friends and neighbours. It’s a big loss not to have that here in town.” ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: