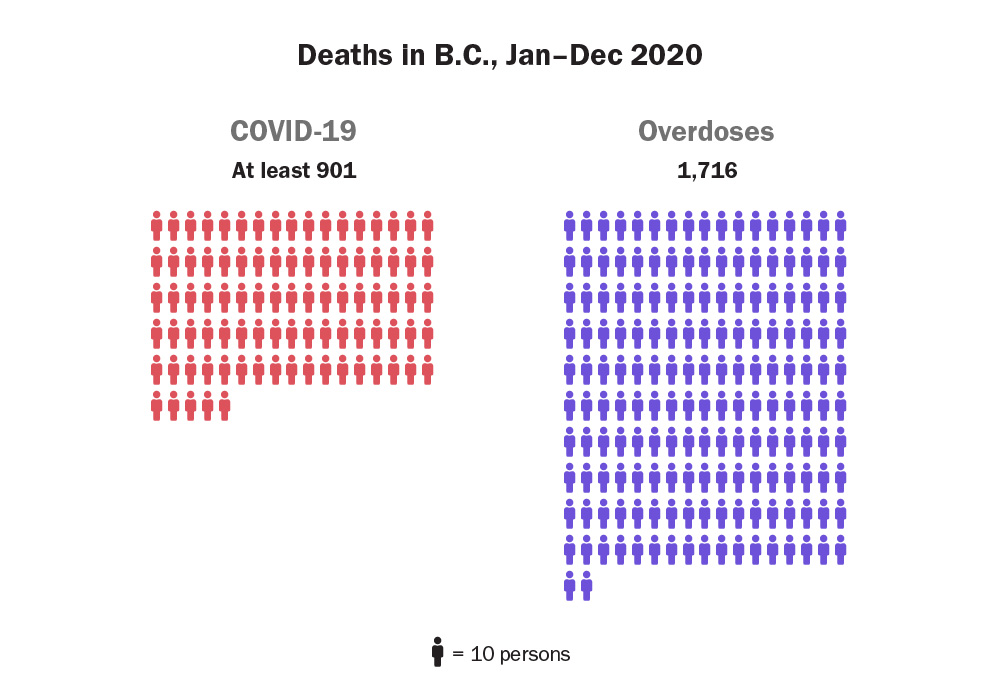

Almost five years after the overdose crisis was declared a public health emergency, at least 1,716 British Columbians lost their lives in 2020 without access to a regulated, safe alternative to poisoned illicit drugs.

That surpasses the 1,549 people who died in 2018, up until now the deadliest year, and is a 74-per-cent increase from last year’s 984 deaths.

About five people died on average each day in the province.

“Thousands of years of life and potential are gone,” said chief coroner Lisa Lapointe as she presented a report on the deaths today. “We must turn this terrible trajectory around.”

Since March, the provincial government has blamed the surge in fatalities on pandemic disruptions to harm reduction services and an increasingly toxic supply of illicit drugs due to border closures and domestic production.

Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson said today the deaths were an “insidious impact of the pandemic,” wiping out progress made in 2019.

But advocates and experts say the province’s small, slow steps to address the crisis, even after the potential impacts of the pandemic on overdose deaths became clear, are a slap in the face to the families and friends of the 6,733 people who have died since 2016.

“We have had years to get ahead of this,” said peer advisor Guy Felicella of the BC Centre on Substance Use. “COVID showed how fragile what we had in place already really was.”

Leslie McBain, who lost her 25-year-old son Jordan Miller to an overdose in 2014, says more than 200 members have joined her organization Moms Stop the Harm in just the last few weeks. “It’s a testament to the amount of grief this crisis is causing.”

McBain said it’s “incredibly disappointing” that the death toll is still rising, five years after the public health emergency was announced.

“What is wrong with this picture? The government is not doing enough, and they do not have a plan,” she said. “I think that is shameful and it is unconscionable.”

The province has focused recent efforts on new treatment and recovery beds, training nurses to prescribe medications to treat substance use disorder and expanding eligibility for people to be prescribed pharmaceutical alternatives to illicit drugs.

In September, the province announced it would expand eligibility for safer supply programs and allow more substances to be prescribed.

But no details on timelines have been provided in the months since.

Malcolmson said, “B.C. is leading the way.”

“The work that B.C. is doing on the whole umbrella of prescribed medications associated with practice is groundbreaking in Canada,” she said.

The Globe and Mail reported today that Malcolmson has asked the federal government to decriminalize possession of drugs for personal use in the province.

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry proposed a made-in-B.C. plan to decriminalize illicit drugs in April 2019, which the province rejected.

In December, Vancouver made a similar request to the federal government seeking an exemption from personal possession laws. Talks are to begin next month.

But Lapointe, McBain and Felicella said decriminalization isn’t enough.

A safe supply of pharmaceutical-grade drugs is needed to stabilize people and separate them from the contaminated street supply, they said.

Felicella said the government’s actions on safer supply have missed the mark. Instead of providing people with non-toxic replacements for drugs they now buy on the illicit market, programs have focused on prescriptions for drugs used in treatment.

That leaves users dependent on often-poisoned illicit supplies, he added.

“It’s another reiteration of a prohibition strategy, all of everything we have is rooted in punitive drug policy,” he said. “We need drug reform, and that’s regulated supply.”

Felicella would like to see community compassion club-based models where people can buy pharmaceutical, regulated drugs without fear of contamination.

Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart supported a role for such a model when asked today, noting the city “would be looking forward to even more aggressive models as this crisis is just getting worse and worse and worse.”

Jordan Westfall of the Canadian Association for Safe Supply said not everyone who dies of an overdose has a substance use disorder or addiction.

And he noted that many people prescribed alternatives as part of a treatment program still access the illicit supply.

“We know a lot of people using on the side are dying,” said Westfall in an interview. “We have to honour that, we have to invite them in.”

When The Tyee asked what Malcolmson was doing to prevent deaths among intermittent users or those not ready for treatment, she encouraged people to use with a friend or use the provincial Lifeguard app.

And when asked about expanding safer supply to provide safe replacements for the drugs people currently use, Malcolmson was vague, saying there is “still a lot of runway and work that’s under way” on expanding the current model.

Westfall says the government has missed an almost infinite number of opportunities to avoid this tragic loss of life.

“I think the summer was a critical chance to do more, to do much, much more,” he said. “Why do we wait for COVID to do safe supply? Why on Earth did we have to wait for a separate public health emergency? I think a lot of people got woken up by the response to COVID.”

In the news conference today, Malcolmson denied that the difference between the government’s response to the pandemic and overdose crises showed some lives matter more than others.

Westfall, Felicella and McBain hope this could be a turning point. But they want to see a major investment in the crisis response in the provincial budget expected in April.

If the report on record deaths doesn’t spur bold action, they are not sure what else could.

“It’s never been this bad before, and we’re still slow,” said Westfall. “We don’t need to keep tinkering at the margins when people are dying.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: