Sukhmeet Sachal and his father finally had the chance to visit their gurdwara in Surrey four months after the pandemic began. The first thing Sachal noticed when he arrived: none of the seniors were wearing masks.

“It was basically just me and my dad,” he said.

It was alarming, but Sachal, a medical student, diagnosed the problem immediately.

The Sikh community wasn’t getting effective guidance on the measures needed to fight the pandemic. There wasn’t much health communication targeting cultural communities in a way that landed, like showing Sikhs how to wear masks.

“My ears are covered by my turban, and so a regular mask can’t fit around my ears,” explained Sachal. And for men with long beards, standard-sized masks don’t give the needed protection. But public health guidance didn’t cover those kinds of challenges.

The need to reach Surrey residents became even more critical as the pandemic worsened. The city has had over 10,000 cases and is part of the hard-hit Fraser Health region.

Surrey is largely a blue-collar immigrant suburb. About 52 per cent of its workers can’t work from home because they do manual labour jobs, according to census data. One-third of residents don’t speak English in their homes. After English, Punjabi is most commonly spoken in Surrey.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, researchers have urged health officials to collect data on how the coronavirus is affecting ethnocultural communities, particularly in diverse places like Surrey with high infection rates.

B.C. does not collect such data, except for Indigenous people. But in mid-October provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry did acknowledge a high transmission rate in B.C.’s South Asian population due to many working in essential sectors.

A statistic like this shows the importance of communicating differently to groups that might be left out with existing messaging.

“The English guidelines aren’t even read by English speakers,” said Jaskaran Sandhu, the admin director of the World Sikh Organization of Canada.

“Why do you expect my 60-year-old mother or grandparent to go to the public health website and download the Punjabi version of the guidelines? It’s not enough. It’s about engaging with stakeholders, engaging with the community at the ground level… and contextualizing those guidelines.”

That’s exactly what Sachal wanted to do for gurdwaras like his, the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara on the Surrey-Delta border. He has a master’s degree in public health and to craft a solution he turned to an approach he studied called the PICO process.

P is the population, which in this case was fellow Sikhs. I is the intervention, which is culturally specific education. C is comparison, to determine if the intervention is working, and O is the outcome, which Sachal hoped would be more adherence to public health guidelines.

With the help of his gurdwara, Fraser Health and grants from the Clinton Foundation and Canada Service Corps, Sachal and other volunteers launched the COVID-19 Sikh Gurdwara Initiative.

Special cloth masks were provided to those who didn’t have them, with volunteers and infographics teaching people how to tie them around a turban, as well as how to store and wash them. South Asian-looking people were used in the images.

Sachal wanted people to think “if they’re doing it, we should be doing it.”

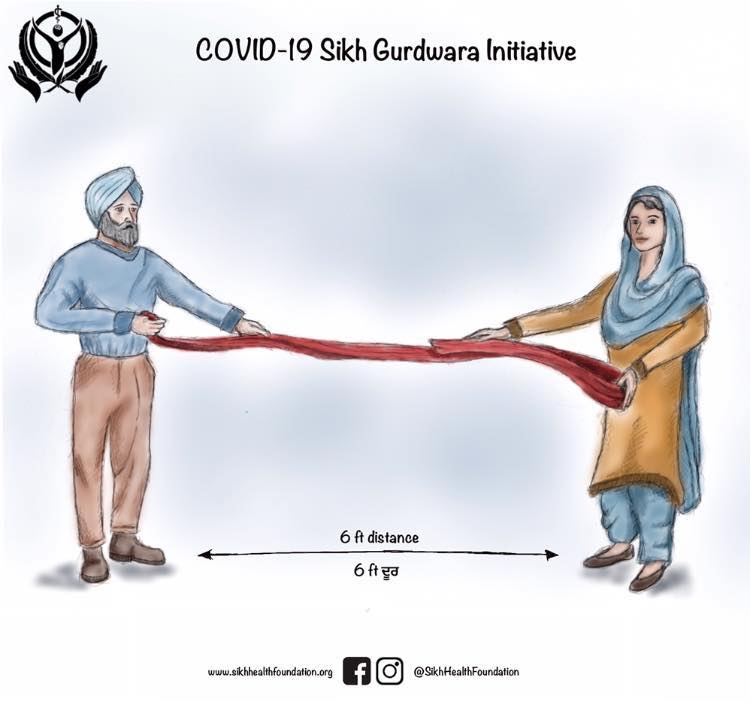

Gurdwaras, like most indoor public places, had markings on the floor and signs to encourage physical distancing. After a stroke of inspiration, Sachal crafted a better illustration to help his community picture physical distancing.

“As I was tying my turban at home, I realized that it’s actually six feet long,” he said. “I was like, this is the perfect way for people to understand this. I drew a sketch of it and sent it to one of our volunteers in the group who does graphic design and got it printed. So the first thing you see when you walk into the gurdwara is a huge cardboard cutout with this drawing of two people at the ends stretching out a turban. You don’t need English, Punjabi, Hindi, French or literacy — you can visualize what six feet apart is.”

The guidelines — reinterpreted — got the message through.

Beyond the blame game

Experts in B.C. and Ontario who work with the South Asian diaspora say they’ve heard a lot of targeted blame for the high numbers in Surrey and Ontario’s Brampton, which shares similar demographics.

Among them: South Asians don’t care about COVID-19; South Asians can’t help but have large celebrations; South Asians will cause a spike in cases due to Diwali; South Asian youth from Surrey were recklessly crowding Vancouver streets on Halloween.

“First, it was the East Asian community,” said Sachal, referring to Chinese people being blamed for COVID-19 early in the pandemic. “Now, it’s the Indian community.”

But Ananya Tina Banerjee, an assistant professor of public health at the University of Toronto, says people looking to blame culture for higher infection rates are missing the really important factors, such as income, housing and access to health care and health education.

“Social determinants have to be at the forefront,” Bannerjee said. “Whenever we see certain racialized communities experiencing health disparity, it’s always alluded to as due to individual cultural factors. When that comes into the media, that’s the narrative that holds.”

Banerjee is used to seeing culture blamed for health outcomes. Before COVID-19, studies linked the high rate of diabetes among South Asian people to their eating habits.

“A lot of the work unfortunately attempted to explain how it’s because of our culture, particularly that we consume primarily high-fat, high-sugar diets, and because of genetic predisposition,” said Banerjee.

But the studies didn’t focus on the reality that Canada’s South Asian diaspora is largely working class and live in car-oriented suburbs.

It’s harder to be healthy if you’re a newcomer who works long hours, commutes by car and lives in a community where there isn’t much health education available in your language, she said.

Also, social investment has not kept up with growth in Brampton and Surrey.

Brampton Mayor Patrick Brown points out that the city receives $1,000 of health-care funding per capita compared to $1,800 in other parts of Ontario. In Surrey, a second needed hospital has been promised for years and crowding in schools has resulted in over 360 portables.

On top of that, many workers in these cities live paycheque to paycheque, and may not have adequate employment benefits or sick leave.

“They can’t stay home and be safe inside,” said the Sikh organization’s Sandhu. “They’re in the trucks, they gotta be on the factory floor, gotta be in the warehouse, gotta be in food processing, gotta be in retail stores. That’s a reality of the community that’s directly often ignored, and it compounds the chronic lack of investment and makes it really difficult to fight transmission.”

Protecting a diversity of communities

On the home front, many South Asian families live with three generations under one roof, a model that has been described as “cradle-to-grave.”

There isn’t much data on multigenerational households, but B.C.’s seniors’ advocate says that about eight per cent of the province’s seniors live in them. And according to Statistics Canada, the Fraser Health region has the highest percentage of them among Canadian urban centres.

The province has detailed safe practices on everything from sex to trick-or-treating during the pandemic. It has also released guidelines and infographics on what to do when visiting a senior at a care home.

But there isn’t much on dealing with the risks if you live with a senior.

“This causes a lot of disruption in family relationships,” said Neelam Sahota, CEO of the non-profit DIVERSEcity. “[Seniors are] traditionally the matriarchs and patriarchs of the family. COVID completely turns it around, and they become the most vulnerable. This completely changes the dynamic, that they need to be protected.”

Sahota says having tangible recommendations on ways to protect such seniors would be helpful. For example, how does a family protect the grandparents if the children they live with are going to school? Or if the working adults are frontline workers?

The seven-member Ramgarhia family in Surrey has been doing a good job protecting grandma and grandpa based on what they know. Tavleen, 22, has lived in the city with her two siblings, parents and grandparents all her life.

Rather than focus on what they can’t do, they’ve been finding things they can do.

Mom tunes into Sikh programming online and on the radio, rather than going to the gurdwara in person. Tavleen is vigilant about physical distancing when volunteering with the COVID-19 Sikh Gurdwara Initiative. Grandpa no longer buys the groceries, but he’s been cooking more and making sweets. He’s also telling more stories to the grandkids about his time in the Indian Air Force.

With fewer places to go, the family has been calling relatives in India, with grandma and grandpa bringing everyone together.

“We facetimed my grandpa’s brother, and it was the first time I had seen his face since Grade 6,” said Tavleen.

Overall, the pandemic has made the family closer.

“I think it’s important to recognize that household dynamics are diverse,” said Tavleen.

A tailored approach

All experts and advocates The Tyee interviewed have called for more data on how ethnocultural groups are affected by COVID-19.

In addition to ethnicity, experts say there are many factors that would help the understanding and reduction of transmission: work, religion, where people live, who they live with and how long they’ve been in Canada.

“There are many cohorts of ‘South Asians’ that can’t be generalized in a brushstroke,” said Satwinder Bains, the director of the South Asian Institute of the University of the Fraser Valley.

B.C.’s Dr. Henry has supported the need for race-based data but said the province does not have the IT capacity to collect it, and that “health actions” are currently what’s prioritized.

But even without the data, Bains says there’s enough evidence that health authorities should be reaching out to a diversity of community stakeholders to ensure COVID-19 guidelines are being effectively communicated.

And to make sure that those guidelines reflect different norms, rather than blaming them for transmission.

“Do we question Thanksgiving as white man’s gathering around turkey? We don’t question the culture behind it. We’ve accepted that it’s normal.”

There are strengths to be recognized too, said Bains. Multigenerational households provide immigrant families economic, physical and social support, especially at a time like a pandemic. Also, ethnic enclaves like Surrey and Brampton offer supports such as places like gurdwaras or being able to speak one’s mother tongue at a medical office.

“I know when we hear ‘enclaves,’ we can break out all kinds of stereotypes about the people who live over there,” she said. “But people congregate and live in places where they feel comfortable. They feel they can open the door and know someone that will speak in their same language and won’t ridicule them. It’s a valuable social safety net.”

Back at the Surrey gurdwara, Sachal’s PICO process proves the power of tailored interventions. If a population is left out in mainstream messaging, it helps to have a targeted approach. His group was contacted by others in Ontario, California and Kenya who immediately connected with the infographics.

You don’t need to be in a hospital to help people in a pandemic, said Sachal.

“It’s all about preventative education to stop people from having to go to the hospital in the first place.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Coronavirus, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: