With six-month-old Kaleb nestled in the crook of her arm, Katelynn Innes picks a purple Sharpie and writes the name of Kaleb’s dad, Sean Kyle Dudoward.

Then Innes encircles the words in a big purple heart, and writes, “We love you forever” and “miss you always.” Beside her is Dudoward’s sister, Shannon Watts. Dudoward died on May 13, just a month shy of his 28th birthday.

Finally, Innes adds, “My daddy — miss you, love Kaleb.”

On Overdose Awareness Day on Monday, organizers in the Downtown Eastside unveiled a memorial wall — white painted plywood sheets — where those who have lost friends and family to overdoses can write down names and messages.

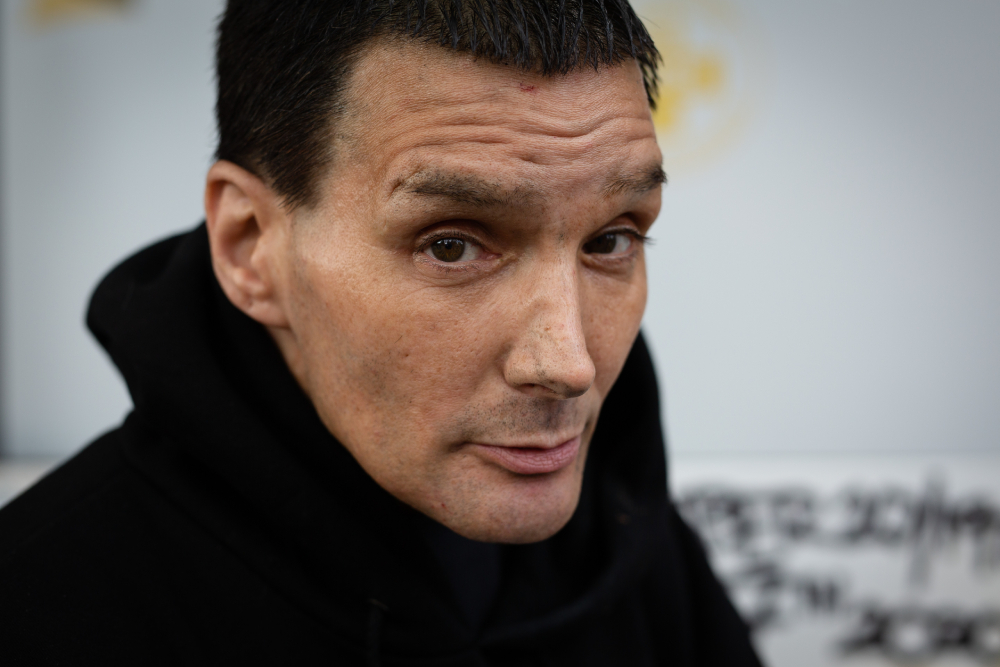

Graffiti artist James Hardy, also known as Smokey D, had worked to fill in a few spots with faces and messages. Some of the portraits — like that of Thomus Donaghy, an overdose prevention worker who was stabbed to death while working at a site in July — are based on real people, while others are fictional creations.

The wall will stay up outside Carnegie Community Centre at Main and Hastings Streets for the next three months, but the plan is to find a permanent spot for the wall.

“What we’re trying to do is use this as a launching pad to have something permanent, something that can be here forever to remember this time,” said Sarah Blyth, a founder of the Overdose Prevention Society at 58 E. Hastings Street.

“(So) people in the neighbourhood, when they want to go say hi to someone who died unnecessarily, before their time, they can go say hi to them.”

While British Columbia grappled with COVID-19, another health crisis was also unfolding, one that would prove deadlier than the coronavirus pandemic. After making some headway in reducing overdose deaths in 2019, fatalities shot up again in the first seven months of 2020.

The increase in deaths coincided with some services being cut back, the illicit drug market becoming more unpredictable and toxic, and no visitor rules in many SRO buildings leading more people to use alone.

In May, 171 people lost their lives to suspected overdose deaths, at that time the highest monthly number ever recorded in the province. In June, 177 people died of suspected overdoses; in July, 175 people died according to the BC Coroners Service.

In recent months, so many people have died in the Downtown Eastside that there’s a risk some people will be forgotten, Blyth said.

“One person at the street market said to me the other day: ‘People just die and... another person dies, and they’re just lost,’” Blyth said. “We need a place to put them.”

There’s another reason a permanent memorial wall is so important, Blyth said: what’s happening right now — the rising number of deaths, the lack of political will, the politicization of a health crisis — is wrong.

“We’re going to have to remember this for being a terrible, terrible time,” Blyth said. “I think that time will come when we make sure people get the help they need and look at all the things we did wrong.”

During the memorial wall event, and at an afternoon block party and protest on Hastings Street, community members pushed, once again, for change — and for the overdose crisis to be treated as seriously as the COVID-19 pandemic.

To flatten the curve of overdose deaths, activists have repeatedly called for the expansion of safe supply (prescribing untainted drugs to people with substance use disorder) to include options like prescription heroin.

Organizers of the Hastings Street block party also called for more radical changes focused on decriminalizing drug use: repealing Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, releasing everyone who is in prison on drug charges, defunding the police and expanding “safer supply” programs, “including non-prescription programs developed by drug users.”

Suzanne "Indian Princess" Kilroy, who was volunteering at a table set up to help residents send a letter to the federal government, said it was important to “bring awareness of police brutality and the drug war on Downtown Eastside people.”

“The drug war is always violent,” Kilroy said. “We’re trying to help people get homes and housing and bring them to a healthier life.”

Kyle Jesperson, a co-ordinator with Onsite, was also at the block party, along with colleague Rebekka Regan. Onsite is the detox, transitional housing and recovery arm of Insite, Canada’s first legal safe injection site.

Holding signs calling on Premier John Horgan to act, Jesperson and Regan said that along with expansion of medical treatment options like safe supply, lack of housing is also a major factor that is leading to people falling back into substance use.

Regan said that many people complete treatment programs only to find no affordable housing to move into. She said the problem has gotten steadily worse since she first started working at Insite in 2003 because of steadily rising housing costs, gentrification in the Downtown Eastside, and a “not in my backyard” response to new social housing in other neighbourhoods.

“The exit plan of that treatment is to return back into the shelters they were accessing before treatment,” Regan said.

The outcome is often a relapse back into substance use, Jesperson said.

Marten Hill, who went through the Onsite program, said finding housing he actually likes — a one-bedroom apartment with a view — has been a major part of being able to stay sober.

“I’ve also got a dog. I’ve got a part-time job. I’m in a way better headspace,” Hill said.

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: