Genevieve Noel was in the room when Fort McMurray city councillors voted unanimously last month to provide almost eight acres for a Métis Cultural Centre.

Noel, a Métis woman and designer, said she had goosebumps as the votes were counted. The $22-million project offers a chance to reconnect with her Indigenous identity, she said.

And that includes exploring Indigenous food sovereignty as a solution to food insecurity, climate chaos and loss of culture, she said.

“As we were reconnecting with Indigenous culture, it just was so evident to me that the wisdom of traditional Indigenous culture is the way forward. We really need to embrace the Earth and really reconnect,” she said. “The spirituality was another layer that I really appreciate.”

Noel and her husband Maginnis Cocivera are founders of Mindful Homes, a North Vancouver architecture firm that hopes to facilitate “a seamless transition to the post-carbon era in response to climate change.”

The firm has been selected by McMurray Métis to design the project.

“It’s an honour to work with them and help bring all these things back,” Noel said. “It’s really a nice healing process to bring community together, and we want to present the project that way, like we’re all moving forward together, we’re not leaving anybody behind, and people can learn to live together again in a more positive way.”

Bill Loutitt, CEO of McMurray Métis, says Mindful Homes was chosen based on its approach to the project.

“We kind of like the presentation in that it’s a little bit back to the ’60s… but with a little bit more technological advances,” he said. “It’s going to really be an eyecatcher with just the design alone.

“This cultural centre has been on our minds for the last 30 years,” Loutitt said. “It’s not something that was brought up yesterday.”

Noel said the project will revitalize and celebrate the practice of Indigenous food sovereignty.

“We’re designing a totally regenerative project,” she said. “We have a huge food security component, so the whole rooftop is solar greenhouses for food security for the community.”

For communities like Fort McMurray — and First Nations in remote or northern locations across Canada — shipping costs mean access to fresh, organic fruits and vegetables is “so expensive, that it’s unattainable,” she said. “We will be growing lots of food.”

Noel said the project, on an island near the city’s downtown, won’t just involve food production.

“We’re rewilding the site with all the Indigenous plants for medicine and food, so all the berries, the traditional medicines,” she said. “We’re building wetland for bio-filtration of the water.”

And the project will meet standards for net-zero emissions, Noel said. “This will be the first project in Fort McMurray that doesn’t rely on the oil and gas industry… we’re healing the oilsands.”

Noel and Cocivera predict that 20,000 pounds of vegetables could be grown on the roof each year. The centre will also provide space to teach the practice of Indigenous food sovereignty.

“There’s a commercial kitchen on site, and that can be used to transform some of the produce into preserves… canning beets and that kind of thing,” Noel said.

Métis people are traditionally hunters and trappers, she said, and there is a specific protocol for handling animals that are killed.

“Being grateful for the animal and doing a proper spiritual acknowledgement,” Noel said. “They use the whole animal, right, nothing is wasted because it’s a life that’s been taken, so it’s really important to learn the protocol from Elders.

“That’s also knowledge that they want to be able to transmit from generation to generation,” Noel said. “And so, on site there will be… an outdoor space where they can undertake that cultural traditional practice.”

Eduardo Jovel, director of Indigenous Research Partnerships at the University of British Columbia, leads a project at UBC farm exploring Indigenous food security and sovereignty in urban settings.

Intergenerational teachings and giving people a space to learn are important, he said, and the project at UBC Farm provides that space. “The garden has become a place where people begin to reclaim their land literacy,” he said.

“Especially with people that have been uprooted from their traditional territories, they might not have a place to practise their own traditions, or they do not have access to knowledge that might be important to them to understand food sovereignty,” Jovel said. “So, Indigenous food security is what we focus mainly on, on medicines and traditional foods as a way to talk about food sovereignty, to talk about food security.

“The garden in some ways, it provides a venue for dialogue,” he said.

Cocivera says the Fort McMurray building will be a place for tourists to explore Indigenous traditions, but mostly it’s for the community, a place for government offices, family services and child care.

Loutitt said the centre will be an important place for people to learn about Métis practices and the history of the Métis people in Alberta. “It’s been kept under wraps for so long,” he said.

And Loutitt said it should also encourage “participation in the community, and not only in the arts and culture, but there’s business, there’s many areas that we should be more engaged on.”

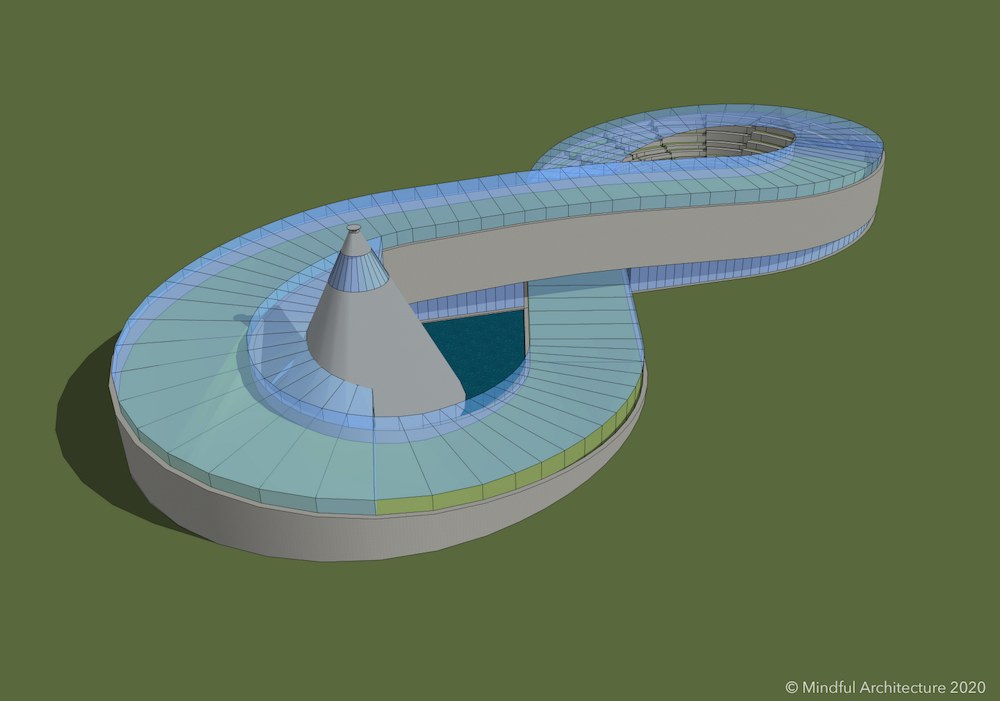

Noel said McMurray Métis felt it was important that the project include a monument to Métis history, so the whole building was designed as a monument, she said. The current design features a figure-eight shape that suggests the infinity symbol, with a walkable green roof.

“It’s like a green roof that goes into the greenhouse on top, and it’s really very contemporary,” Noel said. “When we presented to the Elders, we weren’t sure how they would react to such a modern building, but they totally were really surprised.”

The project is still in the design phase, which could take another year. Construction, which could take two or three years, would start after that.

Noel hopes people recognize this project as the way forward.

“It’s looking to the future and showing a possible way forward for people, another way from the oil.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: