Withdrawal symptoms wait for no one, not even in the middle of a pandemic, said Guy Felicella, recalling the 30 years he spent addicted to drugs.

Felicella, who used heroin while living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, intimately knows the daily struggle to avoid withdrawal.

“You will have to go out, no matter what, and do what you have to do to get that substance,” said Felicella, a now-clean advocate for a safe drug supply and a peer clinical advisor for the B.C. Centre on Substance Use.

The federal government’s relaxation of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, followed last month by more flexible provincial guidelines for prescribers, is welcome news for agencies and advocates such as Felicella who have watched the already-poisoned drug supply become increasingly toxic and expensive as borders close and people self-isolate.

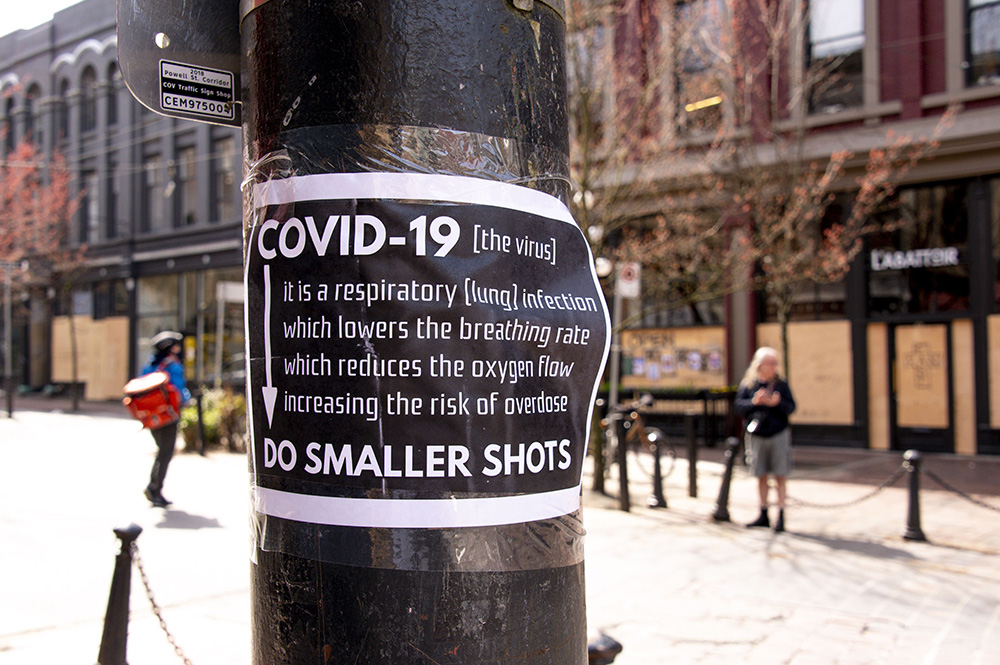

With the supply shortfall, more dangerous basement concoctions are being sold on the street and there is concern that those searching for drugs are at risk of both contracting and spreading COVID-19.

The provincial guidelines, which were hurriedly released to address two overlapping public health emergencies — the opioid crisis, which has killed more than 5,000 British Columbians since January 2016, and the threat presented by COVID-19 — are slowly being adopted by physicians and nurse practitioners, who prescribe drugs; and pharmacists, who have expanded powers to renew, extend and transfer prescriptions, but it is a steep learning curve.

The B.C. Centre on Substance Use has organized webinars and provincial educational bulletins to inform prescribers about the groundbreaking changes that include the ability to prescribe drugs such as hydromorphone, stimulants, benzodiazepines, cannabis and substances to manage alcohol and nicotine withdrawal. Costs are covered by provincial PharmaCare.

The guidelines allow for home delivery by pharmacy employees and prescription renewal by phone. And virtual visits with prescribers are encouraged, especially when COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed. In some cases, people will be allowed up to three weeks supply instead of having to go to the pharmacy every day.

“We want people not to have to go into pharmacies every day... when they should be self-isolating,” said Judy Darcy, minister of Mental Health and Addictions.

“We are trying to flatten the curve at the same time as stopping overdoses and these really unprecedented measures are meant to do both of those things,” she said.

Those eligible for safe supply include people at risk of contracting COVID-19, those with a history of ongoing substance use, people at high risk of withdrawal or overdose, and youth under the age of 19 who provide informed consent, provided there is additional education.

The changes are a great starting point, Felicella said.

“I got a phone call today from someone who has been on a safe supply for two weeks. He has had a challenging life on the Downtown Eastside for 20 years and he says, ‘My anxiety has improved, my mental health has improved, and my overall health has improved, and I am not doing the relentless grind of getting enough [drugs] to not be sick.’”

That means he is not committing crimes because he doesn’t have to worry about withdrawal — and he is able to practice physical distancing, Felicella said.

Education for both prescribers and drug users is now key to the success of the program.

Leslie McBain, co-founder of Moms Stop the Harm, said the province rushed to release the guidelines because of the two health crises, but it is frustrating that the full word did not get out to all prescribers.

“What you had was rollout of a good policy that I hope will continue to progress and evolve, but the infrastructure was not there,” McBain said.

Darcy said the guidelines were put in place at the first legal opportunity.

“As you can imagine, there is a massive effort underway now to get the word out to all prescribers, health professionals, people who are struggling with addictions and advocacy organizations,” Darcy said.

The speed of the changes is unprecedented, so some lag is to be expected, especially as there is usually a gap of 17 years between research and delivering care on the ground, said Cheyenne Johnson, B.C. Centre on Substance Use co-interim executive director.

“This gives an opportunity to protect a very vulnerable population, but it bumps up against all sorts of problems with implementation,” she said.

One problem is that British Columbia does not have a functioning addiction and substance use system of care with a seamless, co-ordinated approach, Johnson said.

“Some people are facing barriers in getting care. It is a challenge on that level. It’s definitely a matter of education,” she said.

Bernie Pauly, University of Victoria School of Nursing professor and a scientist with the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, said it takes time for new guidelines to be implemented.

“But I think prescribers have to get up to speed very quickly on this one because we are talking about people’s lives. We’re talking about preventing an overdose death, so prescribers need to not only know and understand the guidelines, they need to do it really quickly because people’s lives are at stake,” she said.

While there are hopes that the program will bring more people into treatment, some users are complaining the prescription drugs do not produce the same effect as street drugs.

Grant McKenzie, director of communications for Our Place Society in Victoria, said people are starting to access the safe supply, but it does not always get them the high they are seeking.

“People will use it if they have no other access to drugs, but some will then switch back to street drugs when they get the chance,” he said.

Providing drugs that lead to intoxication is not the aim of the changes, according to Darcy.

The objective is safe medication treatment to help people deal with the symptoms of withdrawal, which can be dangerous without medical supervision, to stabilize their lives, and to not rely on an illegal drug supply, she said.

The aim must be maintenance to keep people safe, Pauly said.

“It wouldn’t be good if people are still accessing the illicit market because they are not getting enough,” she said.

As the program slowly becomes part of everyday health care in B.C., advocates are anxious to ensure it stays in place once federal exemptions reach the sunset clause at the end of September.

“I would hope we are able to show the benefits of this,” said Pauly, who also wants to see the government take the next step of decriminalizing personal possession — a policy recommended last year by provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry.

Felicella wants to see policies evolve to providing safe drugs such as pharmaceutical grade heroin, fentanyl and cocaine without prescription, similar to how cannabis is dispensed.

“What we have today is a medical version and it’s a great start and will help many people, but it is not where we want to stay,” he said. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: