It may be hard to believe that the two decrepit hotels seized by the City of Vancouver for mismanagement and horrific living conditions were once high-class establishments for wealthy visitors.

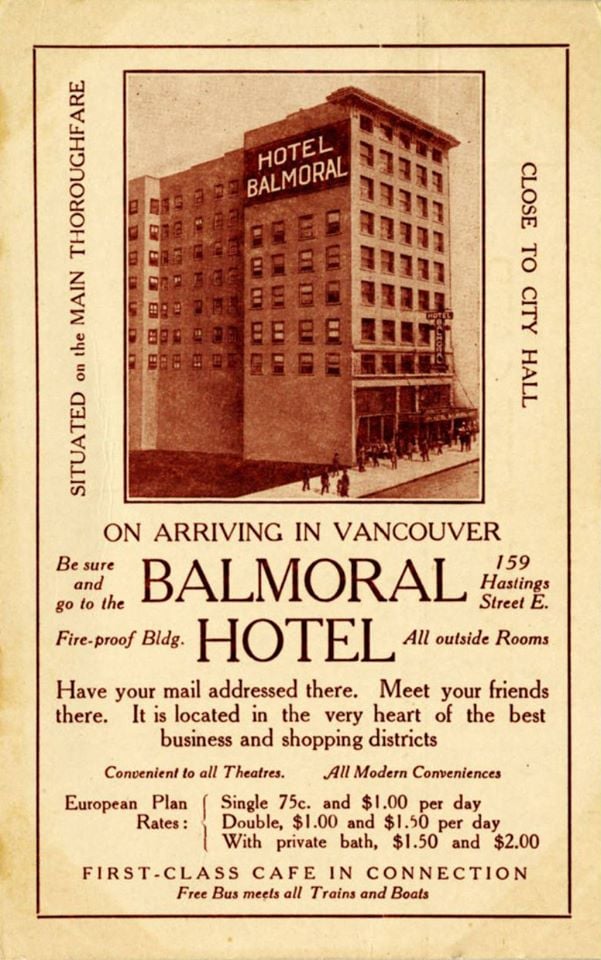

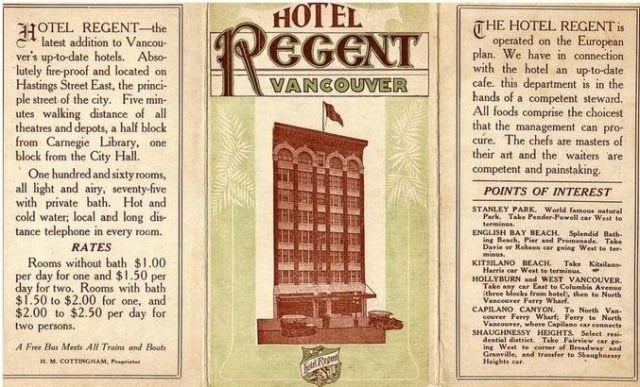

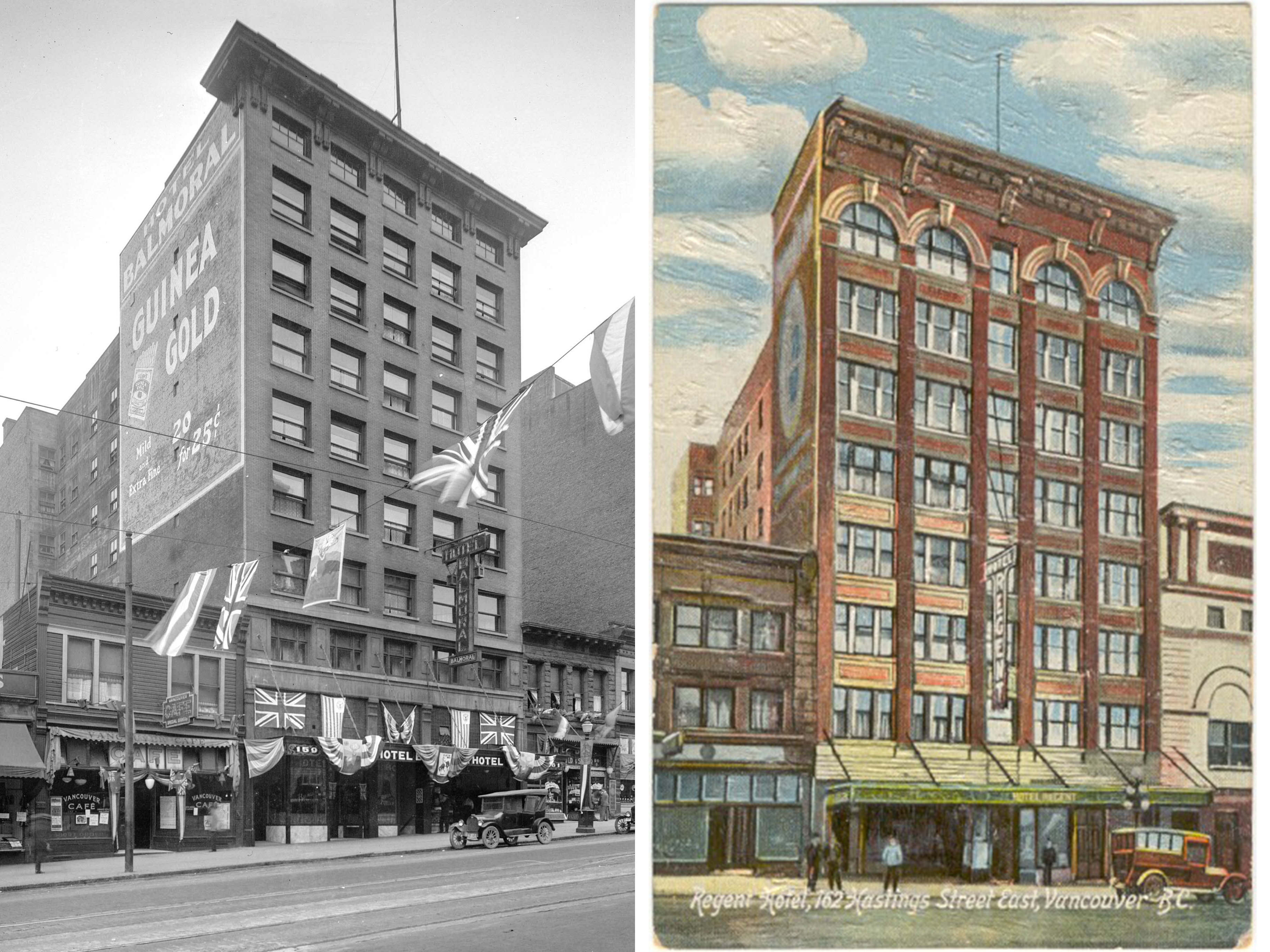

When the Balmoral opened in 1912 and the Regent in 1913, they were not like the blue-collar hotels of the neighbourhood.

Most single-room occupancies on and around Hastings Street were temporary homes for seasonal workers in resource industries such as logging and fishing. These workers would travel north along the coast for months at the time, staying in Vancouver hotels during their downtime between stints.

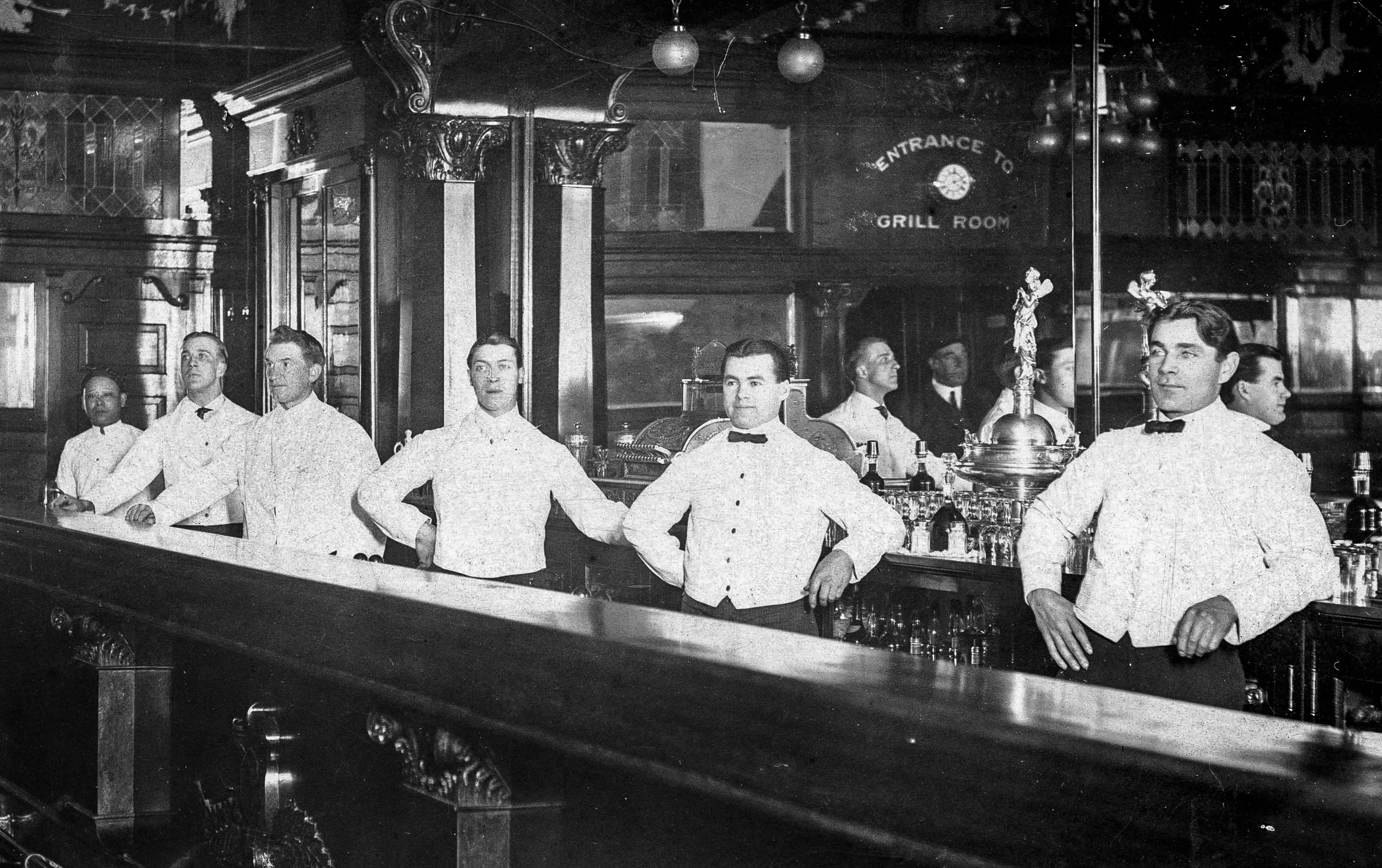

In contrast, the Balmoral and the Regent were fancier establishments catering to wealthy out-of-town guests in Vancouver for both business and pleasure, making them rivals.

They were built during a time of hope and prosperity for Vancouver, which had become established as the province’s centre of finance, manufacturing and shopping and was shedding its image as a colonial frontier town.

Both the Balmoral and the Regent opened just in time to take advantage of the completion of the Canadian Northern Railway in 1915.

The designs of the two buildings have much in common. They are early skyscrapers in the Chicago style, with decorations like arches, pilasters and painted sandstone sills.

Regent developer Art Clemes, who had many properties, was a partner of the Pantages Theatre just next door to the hotel, and the two buildings have similar fine finishes.

The Balmoral shares an architect with other iconic Vancouver buildings that have since been kept in better shape: the flatiron Hotel Europe in nearby Gastown, and the Vancouver Block on Granville Street.

Let’s imagine you rolled into town in the Roaring Twenties. What might you expect from these hotels as a guest?

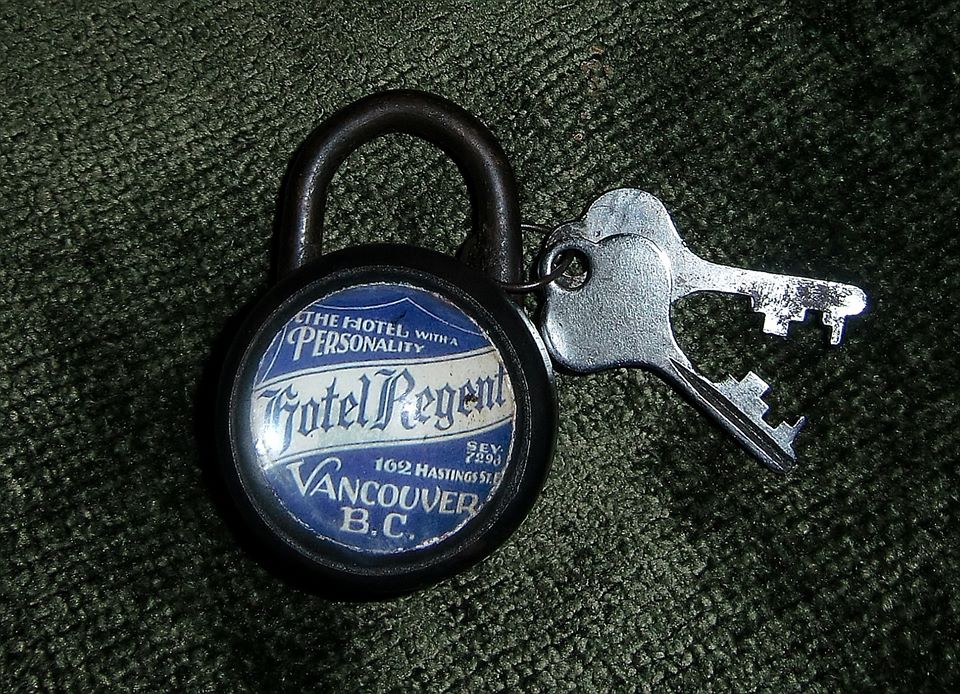

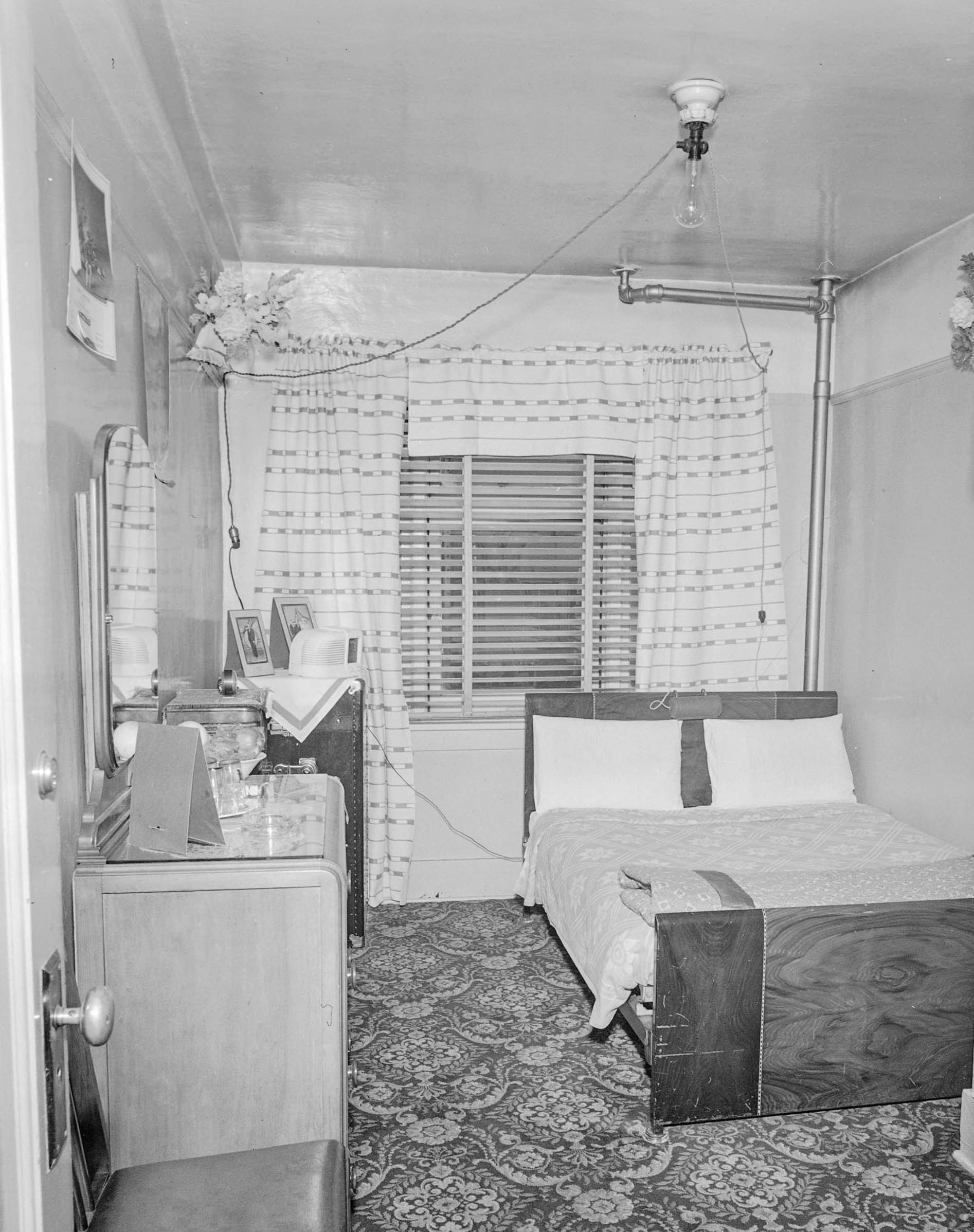

“Painstaking” service, the “choicest” foods and chefs “masters of their art” awaited you at the Regent, according its first brochure. It was a modern place, with 160 rooms, “all light and airy,” about half of which have a private bath. There is also “local and long-distance telephone in every room.”

The Balmoral, just across the street, had its own barbershop, cigar shop and shoeshine stand.

The hotels were located in what was then the city centre, home to city hall, the courthouse, banks, theatres and the Carnegie Library. Hastings, the main thoroughfare, was already known as “Skid Row” by then, a term that originated in Pacific Northwest logging communities because logs would be greased and “skid” on tracks for transport.

The early community here was very male, due to the working population and the traveling public of the time, with shops and services catered to them such as chop houses and pool rooms.

So what happened to the neighbourhood?

What would later be called the Downtown Eastside was always a home for marginalized and transient populations.

During the Depression, accommodations in the original city centre were what many low-income people could afford. It also offered a non-judgmental community. Bars and brothels were plenty. The 1950s brought the death of streetcars. The 1970s saw the area housing psychiatric patients due to the rapid closure of psychiatric hospitals. The 1980s brought the rise of cocaine, and a rise in crime. Gentrification fueled by Expo 86 and then the Olympics sped the closure of SROs beyond a diminishing stretch of Hastings Street.

All the while, the Vancouverites with more money suburbanized, with new urban centres popping up across the region.

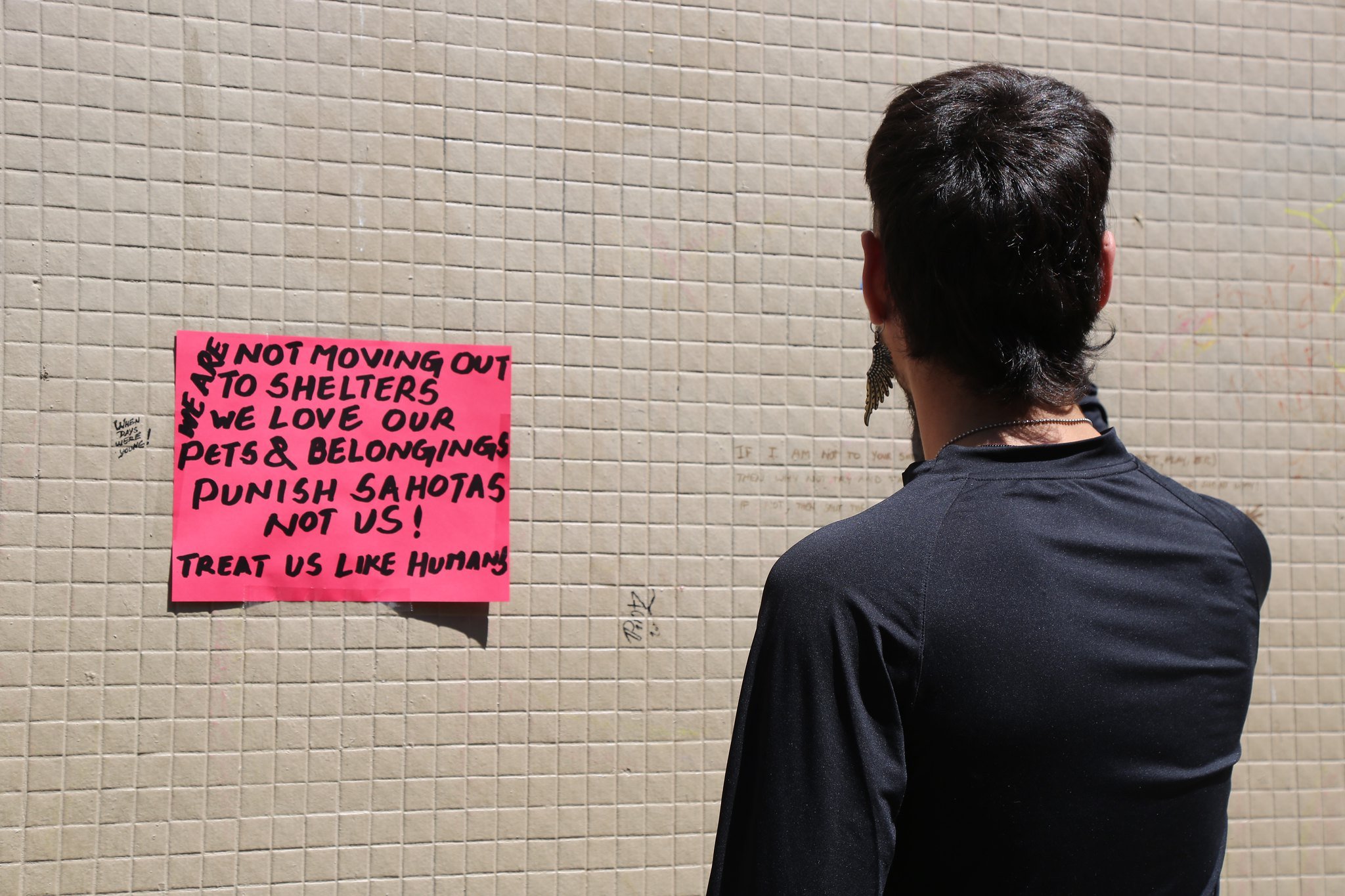

The Sahota family arrived on the scene in the 1970s. They had a “buy and hold” philosophy when it came to profiting from property. Many of the buildings they purchased fell into disrepair. In 1989, the family bought the Regent for $1.5 million. (The Tyee was unable to find when they purchased the Balmoral.)

And so the Balmoral and the Regent, which once boasted of being “fire-proof,” became known as firetraps. The uninhabitable conditions of the family’s SROs, home to residents struggling with poverty, addictions and health issues, led to them earning the moniker of slumlords.

As a result, the city ordered to close the Balmoral in 2017 and the Regent in 2018 over health and safety concerns. Last week, city council voted unanimously to expropriate the properties from the Sahotas for a dollar each. After over a hundred years, it’s a pause in the hotels’ long history of accommodation.

With thanks to Glen A. Mofford for sharing his research. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: