On the Friday evening of June 7, Chief Lee Spahan of the Coldwater Indian Band received an email from Mitchell Taylor, Q.C., head of a federal consultation team acting under the auspices of Canada’s Department of Justice.

The email contained an offer, and an assertion.

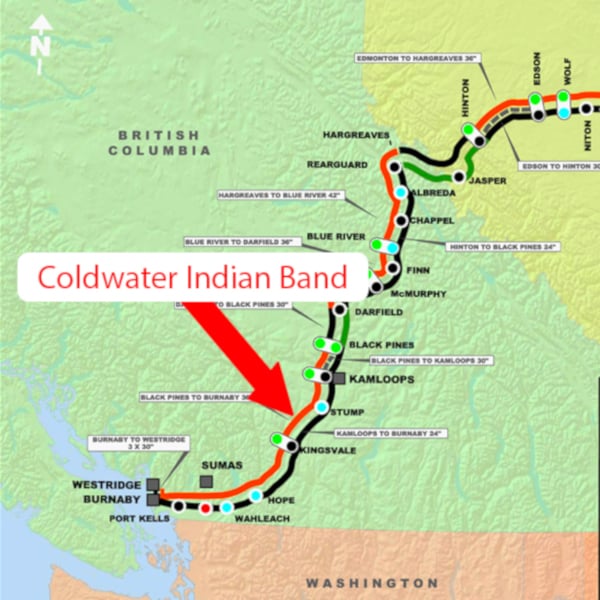

The offer was that the government would take a new approach to deciding where the Trans Mountain Expansion Project (TMX) pipeline would be routed in relation to the Coldwater reserve, whose people are determined to protect the freshwater aquifer upon which they depend.

That issue had remained wholly unresolved after four years of negotiations, court judgments in favour of the Coldwater’s position, countless hours of consultations, and many hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on futile wrangling.

The stakes were high for the Coldwater, for the TMX, and for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who had placed a heavy political bet on using taxpayer’s money to buy the pipeline and guaranteeing its expansion would happen. Last year, the Federal Court of Appeal threw out TMX’s permit to proceed, demanding more rounds of consultation with the Coldwater and other Indigenous nations in the path of the pipeline.

Now, with the new offer came this assertion: “Canada believes this commitment satisfies what we understand to be your key concerns.”

But Taylor’s offer did not begin to satisfy the key concerns of the Coldwater. In fact, in their view, it only put their precious aquifer further at risk, and once again failed to seriously evaluate a solution they’d been proposing for years.

The band was asked to respond to the government’s offer by June 12 — in just three business days. What had been a plodding process suddenly was moving fast. In fact, just 11 days after the emailed offer arrived in Spahan’s inbox, the federal government would announce (again) its approval of TMX, claiming in the process that it had done everything required of it to consult and accommodate Indigenous communities like Coldwater.

On Sept. 11, Trudeau asked the Governor General to dissolve the current parliament. That day he flew to Vancouver to start his bid for re-election with a speech that did not mention Canada’s Indigenous peoples.

The Coldwater Indian Band were busy too. That same day, they filed a Notice of Application in the Federal Court of Appeal that may hand pipeline opponents the keys to locking the project shut for good — or least spannering the works for months, if not years.

It’s not as if the Ncletko, or People of the Creeks, as the Coldwater are known, haven’t made their feelings known previously. Time and again, Chief Spahan and his people have told Canada they don’t see Trans Mountain as being in their interests at all.

“Canada’s Friday Night Proposal,” as they call Taylor’s emailed offer in their current application to the Court of Appeal, added insult to a long list of injuries that Trans Mountain has inflicted on the Coldwater — not least of which is that the existing pipeline actually trespasses on Coldwater’s reserve, and, in their view, has been operating illegally for years, and still does.

This is the long and winding story of how a reserve population of a little more than 300 people (out of a band membership of about 850) inhabiting a tiny sliver of British Columbia became vital to the fate of Canada’s most contentious public project.

The Coldwater Indian Reserve is nestled in the Coldwater River Valley, about three hours east by car from Vancouver. It is in country where the coastal rainforest transitions to interior pine forests, and farms start to look more like ranches.

South of the town of Merritt, the Coldwater Road winds and dips through timberlands and hayfields to a river that hosts steelhead, coho and chinook salmon, occasionally even sockeye, but whose water levels are a fraction of what Spahan recalls from his childhood.

In Spahan’s world, water is life — for fish, and for his people.

In July 2018, when Trudeau traveled to the Fraser Valley community of Rosedale to meet with British Columbia First Nations that support the pipeline, Spahan issued an open invitation to Trudeau to visit his community — just 150 kilometres away. He never received a reply.

Had Trudeau travelled to Coldwater, Spahan would have shown him where, a few minutes’ drive from his office, yellow markers announce a right of way for the underground passage of the existing pipeline. Back in 1955, when the original pipeline was built, the band was awarded a one-time payment of $1,292, plus $1,125 in damages to compensate for loss of timber during the pipeline’s construction by the Trans Mountain Oil Pipeline Company. That was standard practice on many reserves along the pipeline route — payment of $1 per “lineal rod,” a surveyor’s measure equalling 16.5 feet.

How much the Coldwater even knew about this transaction at the time is arguable, since as wards of the federal government, First Nations people had little decision-making power back then. But when Kinder Morgan became the new corporate owner of Trans Mountain about a decade ago, that triggered a requirement that the right of way be renegotiated. It was an opportunity for the band to negotiate improved compensation and to push for modern environmental protections.

The federal government’s fiduciary obligation to the band required the minister to act as though the minister was a person managing his or her own land, according to Matthew Kirchner, a lawyer for the band. In other words, the government’s duty was to wring the best deal for the band out of the company, just as a prudent person would try and get the best deal for themselves.

Instead, Kirchner told The Tyee, the minister at the time rubber-stamped the new easement. No talk of improved compensation, nor of environmental standards unvisited since the 1950s — even though there has already been a leak from the pipeline that has contaminated Coldwater land, and that still hasn’t been cleaned up.

The Coldwater went to the Federal Court of Appeal and, in 2017, the court ruled the federal government failed its duty to the band and ordered it to negotiate a new easement. So far that hasn’t happened. Trans Mountain Corporation, running the pipeline today on behalf of all Canadians, is “operating without an easement right now,” Kirchner said. Nothing has changed in the now two years since the court ordered Canada to seek a new easement. As far as the band is concerned, “They are in trespass. They are there with no authority,” Kirchner said.

The Coldwater reminded the government of this in July 2018, and in September that year it proposed a Resolution Framework that “would allow our governments to move past Canada’s breach of fiduciary duty.” The federal government eventually appointed a negotiator but has not proposed how to resolve the argument over the easement. Hence the Coldwater’s assertion, repeated in its new filing to the federal court last month: “That existing pipeline is in trespass.”

As for the government’s approval of Trans Mountain’s plans to expand the pipeline, the Coldwater joined with five other First Nations in a separate case seeking to overturn that decision. That’s the seismic ruling they obtained from Justice Eleanor Dawson on Aug. 30 last year, coincidentally the same day that Canada paid the “high end” price of $4.5 billion to buy a pipeline from the Texas-based Kinder Morgan. Indeed, the same day Trudeau and Finance Minister Bill Morneau bought the pipeline, Dawson tore up the “certificate of public convenience and necessity” that the government issued back in November 2016 — the legal device by which it had authorized TMX.

Justice Dawson’s ruling — in short form known as the Tsleil-Waututh Nation decision — was a huge win for the Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish Nations, which argued that the National Energy Board was wrong to ignore fears that a seven-fold increase in oil tanker traffic might adversely affect already endangered southern resident killer whales — not to mention impacts on the nations’ ability to harvest marine resources and access cultural sites in their territories. The court also sided with the Stó:lō, the Upper Nicola Band, the Secwepemc Nation and the Coldwater about insufficient consultation regarding everything from fishing rights to pipeline routing.

That latter issue, pipeline routing, was central to the Coldwater’s specific complaint, yet as Justice Dawson found, “Missing from Canada’s consultation was any attempt to explore how Coldwater’s concerns could be addressed.” The judge ordered the feds to redo their consultations to a standard that actually meets Canada’s legal, constitutional and fiduciary obligations to affected First Nations, and since the government chose not to appeal Dawson’s decision, it was obliged to do just that. It didn’t finalize its approach to that process until Feb. 19 this year, almost six months after Dawson’s order. (In their latest complaint to the court, the Coldwater drily note that “Canada took more time to design its 2019 consultation process than it provided for the actual consultation.”)

Canada’s political point man on the file was Edmonton MP and then minister of natural resources Amarjeet Sohi. While Trudeau never responded to the Coldwater’s invitation to visit their reserve, Sohi did. On Nov. 1, Sohi became “the first minister to set foot on the reserve, ever. I’ll give him credit for that,” said Kirchner. “He seemed well intentioned, but he was not well briefed.” In fact, it was confounding to Spahan and Kirchner that Sohi was unaware that Canada’s existing pipeline, let alone any future one, is in trespass on Coldwater lands.

Spahan showed Sohi around, pointing out where the existing pipeline crosses Kwinshatin Creek. “While we were speaking, children walked across the right of way on their way home from the school,” Spahan said in a follow-up letter to Sohi a few days later. “You have now seen for yourself that there are homes on either side of the pipeline that runs through the very heart of our community. I explained the anxiety my people feel about a rupture, spill or other emergency. Now you can understand why the expansion pipeline cannot run along the existing right of way through the Coldwater Valley, and that an entirely new right of way is required in or around the Coldwater Valley.”

Current plans call for new pipe to be laid fractionally outside the reserve, but on a route that crosses a “recharge zone” for an aquifer fed by Kwinshatin and Skugam Creeks. The aquifer is the sole source of drinking water for 90 per cent of residents on the reserve, and is used for agricultural, irrigation and fire protection on the reserve. The aquifer and the two creeks also have cultural significance for the Coldwater people who use them for spiritual bathing, in sweathouse ceremonies, for vision quests and youth training.

Just before Skugam Creek passes through a culvert under the Coldwater Road, its clear, potable water falls out of a tangle of bushes. On a summer’s day last year, the Coldwater Valley air clouded with smoke from nearby wildfires, Spahan gestured uphill to where his grandmother once hung a cradleboard after she lost a young child. It is a C’eletkwmx tradition to make cradleboards for newborns on which they are wrapped snug so they feel “they’re always being hugged.” If a newborn or a tot dies, a further tradition is to hang its cradleboard in the trees alongside the creek, which “allows the child to continue its passage to the other side.” It is part of Coldwater peoples’ culture and traditions, Spahan said, which they seek to “carry on, so our youth know and understand the ways of our people.”

Spahan told The Tyee protecting the creeks is important for another reason. Along their banks there are “little people” — not the lost infants, but little spirit creatures that can be heard singing at night and in the mornings. They are “protectors of the water,” Spahan said, and they are every bit as real to the Coldwater people, and their spirituality, as they are endangered by an oil pipeline in the wrong place.

When Coldwater pointed out the presence of the aquifer to Kinder Morgan when it owned the pipeline, the band proposed a new routing west of the reserve, subject to an examination of its potential impacts that has not yet been done. Their concerns, and the offer to explore an alternate route, were dismissed. In fact, the company stands accused by Coldwater of having tampered with a geophysical report entered as evidence to support its bid to secure the cheaper route at a hearing with the NEB. This, in the face of a federal official’s advice, tendered to the band the day before the cabinet approved the pipeline the first time, that there was a “high degree of uncertainty” regarding the impact of an oil spill on the aquifer, and that, depending on the nature of a spill, it may be “impossible” to ever return the aquifer to “potable standards.”

The Coldwater band has never said it opposes the pipeline expansion per se. What it did say was that, after the company refused to consider the proffered alternative, the federal government should have commissioned an independent analysis of potential routes but chose to rely instead on the fact that the NEB had already deemed the company’s favored route to be acceptable.

After Dawson’s ruling, in addition to the scramble to redo consultations, the government tasked the NEB with considering, as it had previously declined to do, the effects of marine traffic and pollution on those endangered killer whales. It was given 22 weeks to do so, and in February the NEB’s Robert Steedman announced that, despite the “significant adverse environmental effects” Trans Mountain’s expansion would likely have on the orcas, the project was once again recommended by the NEB for approval by cabinet.

Meanwhile, the consultations had been restarted. Sohi greeted the warmed over NEB recommendation on the marine traffic part of the file with a vow to wrap up the new consultations within a further 90 days, and predicted a cabinet decision by June. Sohi told Global News the teams he had working on the consultations had already met with “close to 85 communities” and that he’d met directly with roughly 50 by the end of February. “At the end of the day, no one community has a veto on this project,” he said.

Which entirely misses two points. One, that “This isn’t a scorecard, that you get a few First Nations onside” along the pipeline route, Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council and holder of both business and law degrees, told The Tyee.

And two, that the government, unlike a company like Kinder Morgan, has a fiduciary obligation to First Nations to act in their best interests. “How is it not a conflict of interest (for the federal government) to be consulting with First Nations,” asked Sayers. “They have a greater obligation to protect our rights (than a company does). It has to do with First Nations’ rights.”

In fact, as the Coldwater’s experience illustrates, Canada was unable to disentangle itself from its inherent conflict of interest when it came to consulting the Coldwater about the pipeline routing.

And so, after the cabinet decision in June to re-approve the project, the Federal Court granted leave to the Coldwater and five other First Nations to appeal that approval, just as they had appealed the 2016 decision. In its September ruling, the court said, “There is a substantial public interest in having the upcoming proceedings decided very quickly one way of the other.” Judicial review of the latest challenges is set for three days during the week of Dec. 16.

The showdown coming in December was previewed last February. Minister Sohi wrote to Spahan requesting a meeting in Vancouver on Valentine’s Day, the single stated agenda item being that “we are wanting to build the relationship with your leadership.” What ensued, in Kirchner’s words, was “a completely worthless meeting, nothing of substance. But now he can say he met with (the Coldwater’s leadership).” This was but one example of the federal government’s ongoing “complete failure of consultation” with the Coldwater, as the band puts it in their latest court filing.

The government offers a different picture. Its 236-page Crown Consultation and Accommodation Report presented in June brags about doubling the size of its consultation teams and that, “Overall, Minister Sohi held 46 meetings with over 65 Indigenous groups along the Project route to help in building relationships and supporting meaningful engagement.” It reports that on Feb. 14, “Minister Sohi re-engaged with Coldwater Indian Band, Musqueam Nation and Tsleil-Waututh Nation. Topics included: potential impacts to marine life, waterways and rights; nation-to-nation relationship-building; and the government’s plan to consult differently by engaging in meaningful, two-way dialogue.”

Chief Spahan and two band councillors drove through the tail end of a snow storm to meet with Sohi. Afterwards, the chief sent the minister a three-page letter saying that when it comes to the issue of trespass, “it is difficult to build a relationship based on mutual respect in the face of Canada’s inexplicable delays in giving this matter the attention it deserves. My community members, my council and I feel disrespected” by Ottawa’s inaction. As for “rerouting the pipeline to avoid our aquifer, you told us you couldn’t make any such commitment.” For that, they would need to have a fact-based discussion with the Crown consultation team instead, Sohi told them.

That’s something the Coldwater had been trying to do since Trans Mountain’s initial application back in 2013. At the time, the company looked at three possible routes, one along the existing right of way with some modifications; an eastern route above the reserve’s residential area (the one now approved, the one that threatens the aquifer); and a west alternative along a natural gas right of way. “Only the west alternative poses no apparent threat,” the Coldwater say, but it has never been studied and, early in the NEB’s initial review, it was unilaterally withdrawn by the company “without notice to or consultation with the Coldwater.”

Alarmed that the NEB was giving no weight to concerns about the aquifer, the Coldwater commissioned a hydrogeological study in 2015 which confirmed that the aquifer supplied most of the reserve’s drinking water and was at risk. When it filed the study with the NEB, Trans Mountain dismissed it as “over-simplified” and denied any “direct hydraulic connection” between the pipeline and the aquifer. It presented no data or analysis to support this claim.

The NEB nonetheless refused to order that the west alternative be examined. The one condition it placed on the company relating to the Coldwater route (known as Condition 39) was that the company file, at least six months before starting construction on a pumping station on Coldwater territory, “a hydrogeological report relating to the aquifer at Coldwater IR (Indian Reserve) No. 1.”

After the project was approved in 2016 but before Justice Dawson’s ruling in Tseil-Waututh Nation, the band filed a statement of opposition to the eastern route. “Coldwater specifically asked Canada to participate in the detailed route hearing but Canada refused to do so,” the band says in its current application. Dawson found that it wasn’t sufficient for Canada to rely on Condition 39 in any event, as it “provided no certainty of route or indication of how the NEB would address Coldwater’s concerns regarding the aquifer” once a study was complete. “The Crown did not seriously consider any additional mitigation, including other conditions or alternative routes.”

If the Coldwater believed that Federal Court order would make the government finally show quick and serious attention to their concerns, they were mistaken. Minister Sohi wouldn’t engage directly, referring the Coldwater to Mitchell Taylor’s team. It wasn’t until early March this year that the government signalled a willingness to discuss alternative routes and to study the aquifer; it was on March 15 that the company agreed to work with the Coldwater to “jointly agree upon an option” for routing the pipeline; it was at a meeting on April 10 that a process for doing so was agreed. “This was the first and only meeting where it felt that concrete steps were being made towards a meaningful dialogue on routing,” the Coldwater now say.

Work was begun on the aquifer and west routing studies, but it quickly became apparent that none of the work could completed before the June 18 cabinet decision deadline.

Spahan asked Taylor in a May 7 letter for a detailed written explanation as to how the government intended to fulfil its duty to consult. He told Minister Sohi on a phone call three days later that the Coldwater “was, again, in the position of being squeezed by the Crown’s deadline for a GIC (Governor in Council) decision without essential information about the aquifer and having just started to study the west alternative route.”

Instead of a written response from Taylor, the band received a letter from Trans Mountain president Ian Anderson who now works for the government inasmuch as Canada owns the company he heads. Anderson committed the company to examining the west alternative, but also hedged by saying Trans Mountain retained full discretion to reject that route, whether or not the hydrogeological study had been completed on the eastern route. This “significant retraction” from an agreed process to jointly agree on the new route was a “major step back,” the Coldwater have since told the court.

It also didn’t help that Trans Mountain, without any discussion with the Coldwater, had written to Natural Resources Canada asking for amendments that would substantially water down Condition 39. Spahan told Taylor in early June that the government had no legal authority to make the change that Trans Mountain was seeking — and again, he asked how, with the cabinet deadline just two weeks away, Canada intended to fulfil its duty to consult.

On June 6, the Coldwater met a government deadline to submit to cabinet its perspective on the consultation process that cabinet would rely upon to decide whether its redone consultations satisfied Justice Dawson’s demands in Tsleil-Waututh Nation. Obviously, from the Coldwater’s perspective, the consultation process had failed. By filing its report, the Coldwater considered the consultation process closed.

The next day, or evening — at 7:04 p.m., to be precise — Taylor sent his email attaching out of the blue a new approach from Trans Mountain entitled “Proposed Trans Mountain Commitment to Coldwater.” Taylor asked for a response by June 12. The “commitment” to the Coldwater established for the first time — and without any discussion with the Coldwater — a Dec. 31, 2019, deadline for completing the hydrogeological study. It also said a feasibility study of the west alternative would be completed by Jan. 31 next year. Coldwater and the company would then attempt to reach “consensus” on a route, but if not, a final decision would be made by the NEB — or actually its renamed replacement, the Canada Energy Regulator.

The Friday night proposal would place a time limit on the study “that threatens to undermine the scientific principles on which the condition is based,” the Coldwater say, “… because the study will, at best, be incomplete.”

The Coldwater flatly reject Taylor’s assertion that government fulfilled its obligations by, in his words, “setting out, with certainty, how a route will be chosen — on what basis and with what information.”

In an interview on Sept. 21, Chief Lee Spahan told The Tyee he’s not sure how much time the long-sought-after aquifer study will take, but he’s quite sure the government and the company are actively working against the best interests of Coldwater.

“I am very, very, very frustrated,” Spahan said. “It’s just dragging us through the mud. Our people are so frustrated that even today the pipeline is in trespass, they don’t respect Coldwater, that respect is not shown by the government or the company. They don’t want to be fair about anything.”

Spahan said the study will take as long as it takes, that it cannot be rushed because it is critical to his membership that they be properly informed before deciding what route, if any, TMX will take in relation to Coldwater and what threat, if any, the membership will tolerate to their drinking water. “What is Canada or Trans Mountain going to do when, and it’s when, not if, that water gets contaminated?” Spahan asked.

In her ruling last year, Justice Dawson was withering in her catalogue of Canada’s failings on the TMX file. In the end, she wrote, “more was required of Canada.”

In a statement to The Tyee last week, Natural Resources Canada said in response, “the Government of Canada launched the most comprehensive consultations with Indigenous groups and communities that it has ever conducted for a major project.” It committed to moving forward on the TMX project “in the right way... and that is exactly what we did.”

Its re-approval of TMX “was based on facts, science-based evidence and what is in the public interest... The Government of Canada will respond to Coldwater’s judicial review application in accordance with the expedited timeline set by the Federal Court of Appeal.”

In the end, the government “remains confident” in the project, in part because it did “more,” as instructed by Justice Dawson.

But more than a year after Justice Dawson’s decision, Spahan says the outcome of more is less.

“It’s a flawed process. They may consider it consultation, but I don’t. They talk about reconciliation and implementing UNDRIP (the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), yet they don’t want to respect the decisions we make.”

“Neither side has played all its cards yet,” observes Alexandra Woodsworth, campaigns manager at Dogwood, a non-profit advocacy group opposed to the TMX. “But Indigenous legal challenges stopped Trans Mountain in its tracks once before, and there’s every reason to believe they can do it again.

“Since the pipeline runs so close to Coldwater reserve land,” she said, “the federal government has to meet an extra high bar to prove that it has fulfilled its legal obligations to protect Coldwater’s interests — a fact they’ve already proved in court. Since Trans Mountain threatens 90 per cent of Coldwater community members’ fundamental right to clean, safe drinking water, it’s hard to see how those interests have been protected.”

She concluded, “A legal victory could play out in different ways, but whether the approval is overturned outright, or the court orders other remedies that lead to route changes or permit hold-ups, construction delays would be almost inevitable. And every month Trans Mountain’s bulldozers sit idle means increased costs — and possible shifts in the political or economic forces that will determine the fate of this project.”

“In the end,” says Spahan, “nobody wants to listen to Coldwater. Nobody respects us. They just want to keep railroading us.” ![]()

Read more: Energy, Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: